The Green, also referred to as the Douglaston Community, was one of New York City’s oldest African American communities. Located in what is now Jamaica, Queens, The Green began sometime around 1830 after the abolition of slavery in New York — there is little documentation of the slave population in Jamaica and about the community’s shift from primarily Caucasian and agriculture-centered to racially diverse and urbanized. Although those who lived in The Green had developed a sustainable and close-knit community, many in the community faced regular hostility from the area’s white residents, who expressed hesitation toward the community’s expansion.

By the 1740s, Long Island housed more enslaved Africans than the rest of the colonial regions. Long Island’s proximity to Manhattan was in part more limiting for those enslaved on Long Island since urban slavery institutions had spread further east. Long Island’s geography further exacerbated the poor conditions of slaves, since slaves could not simply escape on foot — slaves had to take an extremely risky swim, be smuggled off by boat, or take commercial transportation toward the city. Slavery on Long Island also differed from most of the country in that agriculture was not particularly successful due to harsh winters, meaning that slaves had to work in the fields for part of the year and take on other roles during the colder months.

From 1656 to 1776, Jamaica had 35 citizens who owned 59 slaves, according to wills and town records. At the time, it was the largest (or among the largest) slave community on Long Island. By 1800, there were already over 15 freed African Americans living in Jamaica. In the first federal census in the late 1780s, Jamaica had 1,398 whites, 221 slaves and 65 freed Blacks. One of the most prominent voices advocating for abolition was Rufus King, a New York Senator who lived at and names the King Manor Museum in Jamaica. Even after many slaves were freed (and slavery was officially abolished in 1827), African Americans struggled to fit into Jamaica due to lingering racism and hostility toward the community. Churches became centers for the African American population to feel welcome and supported, and a number of Black leaders emerged from Jamaica who aimed to create a community for African Americans to live peacefully without threats from white residents nearby. And just a few towns over was Newtown, a community of freed African Americans established in 1828 in present-day Elmhurst.

One such leader was William Rantous, who purchased a plot of land on “The Green” for $120, which was quite a significant amount for a person of color at the time. His wealth suggested he was a person of interest in the community. Born in 1807, Rantous became a teacher and farmer, and he made his first foray into politics in 1837 when he signed a petition of Long Island African Americans to receive voting rights. Conventions were held in 1840 and 1841 to protest the injustice of being denied a right to vote, and Rantous helped to organize both; the latter conference in Jamaica was held “for cooperating with our disenfranchised brethren throughout the State, in petitioning for the right of suffrage.” He founded an organization called “Colored Persons Loge” in the settlement, yet it’s unclear exactly what their mission was.

Rantous was also a major advocate for educational opportunities for African Americans in Jamaica. In 1841 at the time of the third conference, there were no public schools in the modern sense, meaning that with few regulations, Black students often were left behind since they often could not afford tuition fees or access books. In 1822, the Presbyterian Church in Jamaica set up a free school, and in the 1840s the church offered a more select academy for students of both races. Rantous’ demands were heard when in 1844, a public school system was established, although Rantous still disapproved of some policies. In 1858, he also fought to get a new Black school for Jamaica, but this was not realized until 1886.

Rantous, who at one point owned six properties in The Green and two elsewhere in Jamaica, also financially backed a monthly magazine by Thomas Hamilton, a pioneering Black journalist who acted as Secretary of the American Abolition Society; Hamilton founded and contributed to papers such as The Colored American and The Anglo-African Magazine. Many articles in these widely read publications, both in The Green and elsewhere (including as far as Haiti), featured articles about adjusting to a post-slavery life, commentary on racist and defamatory remarks, updates on runaways, and pleas to the South to advocate for racial equality. Rantous may have been the only financial support for the latter venture, which failed just a few years later. Rantous died in 1861, with some of his goals unfulfilled, but his activism promoted educational activism and abolitionist efforts in the community.

Very little is known about the development of The Green, but census data from 1840 shows a clear residential organization of Black residents, with groups of 8 to 12 households forming. This was mostly absent from the 1830 census, since it seemed as though the Black population was relatively scattered with just a few small clusters of Black households. By 1850, a 60-person group had formed, even though most residents rented their homes. It was likely that the Black households not included in these larger clusters were central to Black-owned farms in a farmer-laborer agreement. It was determined that The Green was its own separate settlement when looking further into census data, which suggests the development of The Green separate from wealthier white areas. This development seemed to mirror those of other New York City African American communities like Weeksville in Brooklyn, Seneca Village in Central Park and Sandy Ground on Staten Island.

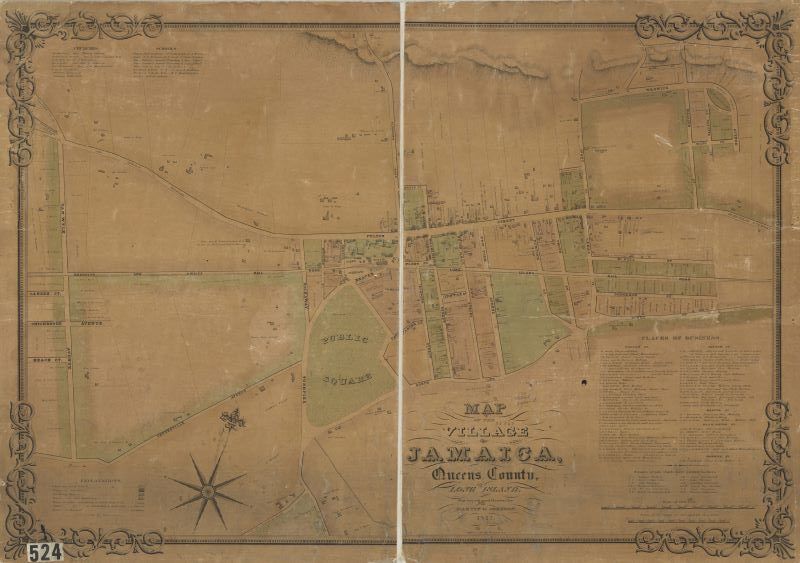

The Green which had a population of at least 100, was located most likely around Douglass St. and what is now Liberty Ave., between 168th street and 175th street. Census data suggests that The Green transitioned from white-owned properties rented out to Black residents to Black-owned homes. These findings are supported by a January 9, 1858 New York Times article which states that following the abolition of slavery, “much cheap land was found on the island, as this was offered at a very small rate, [and] the colored people took benefit of the sale to purchase homesteads for themselves.” The Green had a handful of shops and appeared to have a rather separate economy from the rest of Jamaica.

Much of the Black population in Jamaica banded together since the threat of discrimination and slavery was still very real, even though slavery was abolished two decades prior. It was not rare for agents to hunt down runaways living in the north and smuggle them to the south. And even if they were not runaways, the fear still loomed for those holding certain jobs, such as sailors — sometimes Black sailors were falsely accused of helping slaves escape the south via boat, and the accused had to pay a massive fee or be sent back into slavery.

Such racial tensions are reflected in Rantous’ writings. In one letter signed by 25 residents of The Green, Rantous noted how people from outside the Jamaica area traveled to The Green to block their access to essentials and to prevent safe passage within their community. Rantous was critical of authorities who did little to support the Black community, and he even filed formal complaints about the occupants of a house owned by a Mr. Servass for being “riotous and disorderly.” Reports from a court docket revealed violence between residents of The Green and white Jamaica residents, but all the attacks seem to have been perpetrated by Black residents on white people, not vice versa. These attacks were perhaps carried out in self-defense. Crimes such as battery and assault resulted in a fine of about $20 or 30 days in jail. And in one particularly noteworthy example of the race divide, a Black woman in the community was convicted for shoplifting, while three white women were acquitted of the same crime.

“We complain of the present system of supporting the poor, in consequence of which, that economy so desirable in all public charities, cannot be enforced…” one person wrote in a December 19, 1843 issue of the Long Island farmer, and Queens County advertiser. “It is well known that in the rear of the Wind Mill, near the village of Jamaica, several colored families, many of them from other towns, have rented tenements or remain on sufferance, and in some cases, five or six families occupy one building. These persons will no doubt become chargeable to the town in. the course of the ensuing winter, if suffered to remain as they are at present, many o them without any visible means of support. Is it not the duty of the overseers of the poor, to examine into this matter, and take prompt measures to prevent paupers from other towns, gaining a residence among us.”

“That upper part of this village upon the railroad, called ‘the green,’ has for some time past been infested by some troublesome darkies, who have considerably annoyed a better class of colored people who live there; and we are pleased to learn that Constable Holland is giving attention in earnest upon this subject,” wrote another author in a May 9, 1848 edition of the same paper. “During the past week Justice Bradlee fined a colored man named John Jefferson, three dollars for an assault upon John Cisco, and pelting his bouse with stones. Another colored inhabitant of the green, called Jim Remsen, was sent to jail for thirty days, for petit larceny in stealing a coal and a small piece ol beef from Mr. Richard Owen. It is feared that a large number of idle colored boys are training up, on the green, in the way they should not go. Saturday nights are represented to be most noisy ‘upon the green,’ when drunken negroes go there, bottles in hand, and the fiddle has been known to tune up through the night, and even in disregard of the following sabbath.”

There is little out there regarding the architecture of The Green, as well as little data on education, religion or the community’s dissolution. Most of the property on the grounds of The Green has been industrialized, although there is one lot that may have the remains of a structural foundation of a building from the era. But The Green, despite how little is known concretely about it, was a strong community of Black residents who fought against racism while developing its own economy and seeking the betterment of all disenfranchised groups.

Next, check out 33 Black History Sites to Discover in NYC!