Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Belt Parkway has likely caused many New Yorkers great frustration. Bumper-to-bumper traffic especially by JFK Airport has delayed many trips and aggravated commuters. Yet the Belt Parkway also has plenty of secrets and rich history that might turn road rage into fascination. The original idea of the Belt Parkway was actually a system of parkways, many of which exist today like Grand Central Parkway and Whitestone Parkway, but today the Belt Parkway is a 25-mile stretch. To build the Belt Parkway, much of the Jamaica Bay area was infilled, which subsequently caused extensive flooding and damage during Hurricane Sandy. The Belt Parkway, though, helped pioneer new technology and the development of many of the city’s parks and green spaces. Here are ten secrets of the Belt Parkway, which connects Bay Ridge, Brooklyn with Laurelton, Queens.

The Belt Parkway was proposed by Robert Moses on February 25, 1930, to provide highway access to Manhattan and to connect to parkways already constructed on Long Island and Westchester County. The Regional Plan Association previously planned a “Metropolitan Loop” that would connect the five boroughs, and alongside the Belt Parkway, others proposed as part of the loop included the Cross Bronx Expressway and the Staten Island Expressway. The Belt Parkway was originally referred to as “Marginal Boulevard,” and it was inspired by Frederick Law Olmsted as a route allowing for closer integration of outlying city areas. Construction began in 1934, and it was opened on June 29, 1940.

Along the Belt Parkway, Moses planned a series of “ribbon parks” similar to those found on the Long Island parkways. These ribbon parks were large areas landscaped like a park and Moses ordered for the construction of playgrounds and walkways along the parkway. Moses believed that controlled-access parkways would allow for efficient traffic flow and residential growth. The parkway skirts 26 park areas including Owl’s Head Park, Dyker Beach Park and Golf Course, Marine Park and Canarsie Beach Park.

Mau Mau Island, also referred to as White Island, is a small uninhabited Brooklyn island between Gerritsen Creek and Mill Creek. A mill and bridge were built in the area in the late 1700s, and it was donated to the city in the early 1930s as parkland. The island, though, did not come into existence until 1917. The man-made landmass expanded in 1934 during the construction of the Belt Parkway when sand from the excavation was added to the island. Much of the sand was covered in asphalt to protect golfers in Marine Park from the chance that it would blow away in the wind.

In 2011, the Parks Department began a restoration project on the island to restore the original salt marsh and bird habitat. That same year, a small artists’ collective known as Swimming Cities first hosted a naval battle for the island. From names like Notorious G.I.G. to S.S. Botulism, the “gangs” were required to provide some type of seafaring vessel, many of which were improvised from reclaimed materials. The battle featured boat jousting and a circumnavigational row-powered race around the island.

Plumb Beach is a hidden beach near the Sheepshead Bay and Gerritsen Beach neighborhoods of Brooklyn. You pull off the Belt Parkway on an unmarked exit. The only thing that denotes the beach’s existence is a stylish vendor kiosk with the words PLUMBEACH wrapping it. The small beach attracts kiteboarding enthusiasts due to a southerly sea breeze. Despite heavy beach erosion, the beach is also a habitat for horseshoe crabs every May and June. Now part of the Gateway National Recreation Area, it was originally a separate island until the nearby Hog Creek was filled in with the creation of the Belt Parkway.

The beach’s name perhaps derives from when sailors stopped on the island and munched on native beach plums. Plumb Beach was a popular destination around the turn of the 20th century when a ferry connected it to Sheepshead Bay, Barren Island and Breezy Point. But even before the ferry, the federal government purchased part of the island to use as a mortar battery. Although the island could not sustain the battery, Judge Winfield S. Overton became the island’s “czar” to regain the government’s initial investment, Overton’s five-year lease of the island was cut short after holding “carnivals” with boxing matches, which at the time were illegal. The island was occupied by squatters for a few decades, but they were forced to leave during the construction of the Belt Parkway.

Thanks to the creation of the 26-mile Brooklyn Greenway, you can traverse the stretch of the Brooklyn-Queens waterfront along large portions of the Belt Parkway, first starting at the north end of Bay Ridge to the southeastern end of Bath Beach. Then the Greenway picks up again, as the Jamaica Bay Greenway, from the eastern end of Sheepshead Bay, following the path of the Belt Parkway, all the way to Howard Beach just before John F. Kennedy Airport. The Brooklyn Greenway is not just for biking — it’s open to pedestrians and any other non-vehicular traffic — and it provides wonderful waterfront views of New York Harbor.

The full Brooklyn Greenway remains incomplete however between Gravesend and Sheepshead Bay, and the Brooklyn Greenway Initiative continues to fundraise and advocate for its completion. To show your support for the effort, you can join a fundraiser garden party with the Brooklyn Greenway in the fabulous Naval Cemetery Landscape in September.

Nestled deep in Brooklyn on Barren Island by the Belt Parkway sits Floyd Bennett Field. The once legendary airport opened in 1931 as New York’s first municipal airport. The field has been used by some of history’s greatest aviation figures like Amelia Earhart and Howard Hughes, and it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. The airport was named after pilot Floyd Bennett, who was the first man to fly to the North Pole — although many suspected that he never actually made it all the way there.

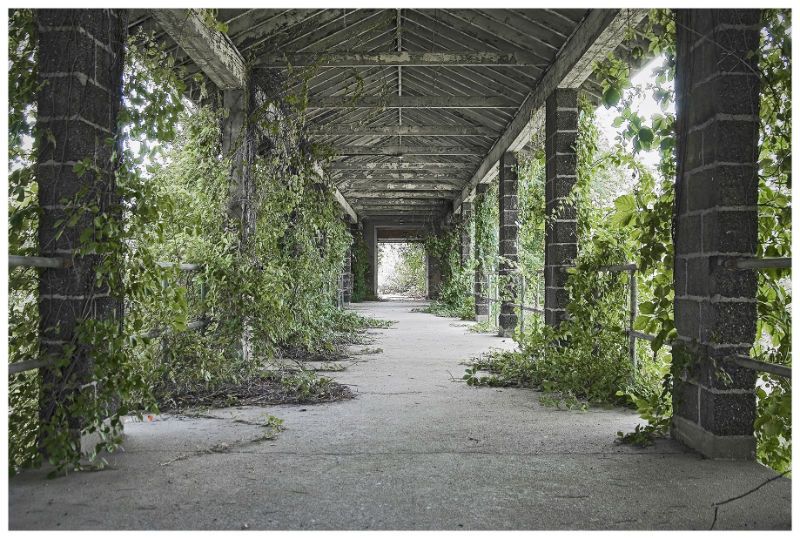

Floyd Bennett Field also was where Douglas Corrigan left for Ireland instead of Los Angeles after being denied permission to make a transcontinental flight. Corrigan gained the nickname “Wrong Way” since he was supposed to fly to the West Coast and mistakenly ended up in Ireland, but many suspect that this was an intentional flight for him to prove that he could fly across the Atlantic. Floyd Bennett Field was also the start and finish point of Howard Hughes’ legendary circumnavigational flight around the world in 1938. For decades, Floyd Bennett Field sat relatively abandoned starting from when the Navy deactivated the site in 1971. Today, several buildings have been restored, while others still sit abandoned. Still, it is a busy recreational site that hosts a vintage aircraft restoration facility, film location shoots, outdoor camping, and other activities.

The stretch of the parkway between Fort Hamilton Parkway to Knapp Street is named after Leif Ericson, perhaps the first European to set foot on the American continent. Shore Parkway was renamed “Leif Ericson Drive” in 1969 by the City Council to acknowledge the large Scandinavian population in nearby Bay Ridge. In 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson proclaimed October 9 as “Leif Ericson Day” to honor the heritage of Norwegian New Yorkers, many of whom have ancestors who arrived in New York in 1825. Two other Parks Department properties in Brooklyn are named after the explorer: Leif Ericson Park and Square lie on five blocks between 66th and 67th Streets, and a namesake playground opened in 1936 nearby.

Over two decades later, the state legislature named the section between Coney Island and Laurelton the “POW-MIA Memorial Parkway.” This section honors prisoners of war and those missing in action, as well as their families.

Construction of the 36-mile-long Belt Parkway also involved the installation of a few highway design advances that had been tested on the Long Island parkways. This included dark-colored main roadways and light-colored entrance and exit ramps. Additionally, new sodium vapor light fixtures were installed on top of traditional timber light posts. The New York Times even called the $30 million Belt Parkway “the greatest municipal highway venture ever attempted in an urban setting.”

The parkway was built on a more grassy terrain than most highways of the time, surrounded by trees and other greenery. The parkway was also closed to commercial traffic when it first opened, banning station wagons and commercial trucks of any size. Additionally, to build sections between exits 7 and 8, parts of Coney Island Creek were filled in, finishing the process of turning Coney Island from an island into a peninsula.

Although construction on the highway was quite successful and quick, the entire route was interrupted for a two-mile stretch between Sheepshead Bay and Marine Park. Local property owners feared that the Belt Parkway would create a “Chinese wall” that would cut them off from the beaches. Resident concerns delayed the completion of the parkway for nearly a year, although Moses would open the final two-mile Brooklyn stretch in May 1941, much to the dismay of these Brooklynites. However, this was not the first time that residents were displeased with the creation of a highway through their community; Robert A. Caro, who wrote a biography of Moses titled The Power Broker, analyzed how the creation of a “Chinese wall” on the Gowanus Parkway accelerated the process of deterioration west of the waterfront.

The widening of the Belt Parkway also did not bode particularly well with the community. Originally constructed as four 12-foot-wide lanes and a wide grassy median, the Belt Parkway was later expanded to six lanes. This expansion occurred in the late 1940s following increases in postwar traffic. The Laurelton Parkway section was actually widened even more to seven lanes.

In March 1971, Governor Nelson Rockefeller announced plans for converting 15.6 miles of the Belt Parkway into an Interstate highway. The plans would reconfigure the section to comprise of 10 lanes, with six used by automobiles and two in each direction for trucks and buses. The $213 million proposal would potentially unclog truck congestion on Brooklyn streets. Yet the proposal to expand the Belt Parkway was met with criticism — many considered the plan a potential “major air pollution source” and believed it would benefit truckers traveling between New Jersey and the south shore of Long Island, not Brooklyn.

Governor Rockefeller soon withdrew his support for the Belt “truckway” on May 20, 1971. However, the Regional Plan Association is reconsidering this proposal as part of the “Southern Gateway” mobility plan. The RPA reconsidered the proposal, which would allow trucks to travel between the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and JFK Airport.

Hoffman and Swinburne Islands are situated in Lower New York Bay, east of Staten Island and west of the Belt Parkway. The artificial islands were used as quarantine stations for immigrants who showed symptoms of contagious diseases en route to Ellis Island. To prevent the occurrence of a deadly epidemic, a concrete wall barricaded each of the islands. Swinburne Island housed a hospital dedicated to cholera and yellow fever cases, a crematory and a mortuary. Hoffman Island housed a “Quarantine of Observation” for those exposed to smallpox or typhus. Hoffman island also contained a disinfecting chamber in the New Administration, which featured a series of narrow passageways that held overhead tracks where baskets containing contaminated clothes were pushed.

Hoffman and Swinburne Island were abandoned until 1938, and that same year the islands were used as military training centers. The remains of Quonset huts from World War II remain on Swinburne Island. After the U.S. Maritime school closed in 1947, the islands were abandoned until the Parks Department acquired the islands for $10,000 in 1966 to preserve the natural landscape of the bay and harbor. Now, the artificial islands are home to birds such as the snowy egret, black-crowned night heron and the great black-backed gull.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Bay Ridge!

Subscribe to our newsletter