Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Today, the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library’s Treasurers will open at Gottesman Hall, a 6,400-square-foot marble exhibition space inside the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, the landmarked 42nd Street library. On display will be more than 250 items spanning over 4,000 years of history from the Library’s renowned research collection, many priceless artifacts of national and international significance. As Declan Kiely, Director of Special Collections and Exhibitions for the New York Public Library, comments: “The two chief functions of this exhibition are to provide visitors with an emotional experience and a mine of practical truth… My hope is that visitors will gain renewed understanding and appreciation for the variety and diversity of the Library’s special collections, and how the objects featured in the exhibition have been preserved for future generations.”

The Polonsky Exhibition exhibition is broken up into nine distinct sections: Beginnings, Performance, Explorations, Fortitude, The Written Word, The Visual World, Childhood, Belief, and New York City. Each section aims to tell a unique story, connecting each item on display to a broader historical narrative, one which is expanding continually. In addition to written label texts for each item, a select few will also be accompanies by an audio guide featuring commentaries from American actress, playwright, and professor Anna Deavere Smith.

Here are 11 fascinating items on display at The Polonsky Exhibition!

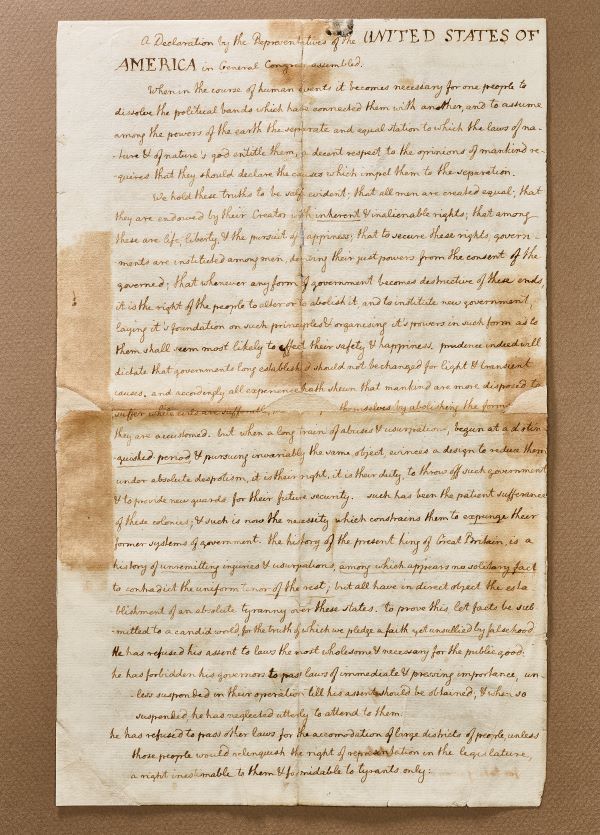

As one of only six manuscript versions known to have survived in the hands of Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration of Independence on display at the Polonsky Exhibition is a sight to behold. In particular, this version of the Declaration of Independence was made by Jefferson for a friend shortly after the document’s ratification on July 4, 1776, as a means of preserving his original draft of the document, which had been significantly altered by the Second Continental Congress. A striking difference between the original and final versions is the substitution of “inherent and inalienable rights” for “inherent and unalienable rights.”

Most important in terms of significant changes are a series of underlinings highlighting passages that were removed from the final version. One of these included a passionate rebuke of African chattel slavery and the slave trade, with Jefferson referring to it as being a “cruel war against human nature itself” and “an assemblage of horrors.” However, though almost exclusive blame was placed on King George III and the British for bringing slavery to the colonies, Jefferson himself was a known enslaver—having owned more than 600 slaves throughout his life. In the end, while even this version of the Declaration of Independence might not have actually fully supported the notion “that all men are created equal,” it gives us a glimpse into what could have been. It allows us to speculate on what the future of the new republic might have looked like if questions on the validity of slavery had been brought to the forefront of one of the republic’s most important founding documents.

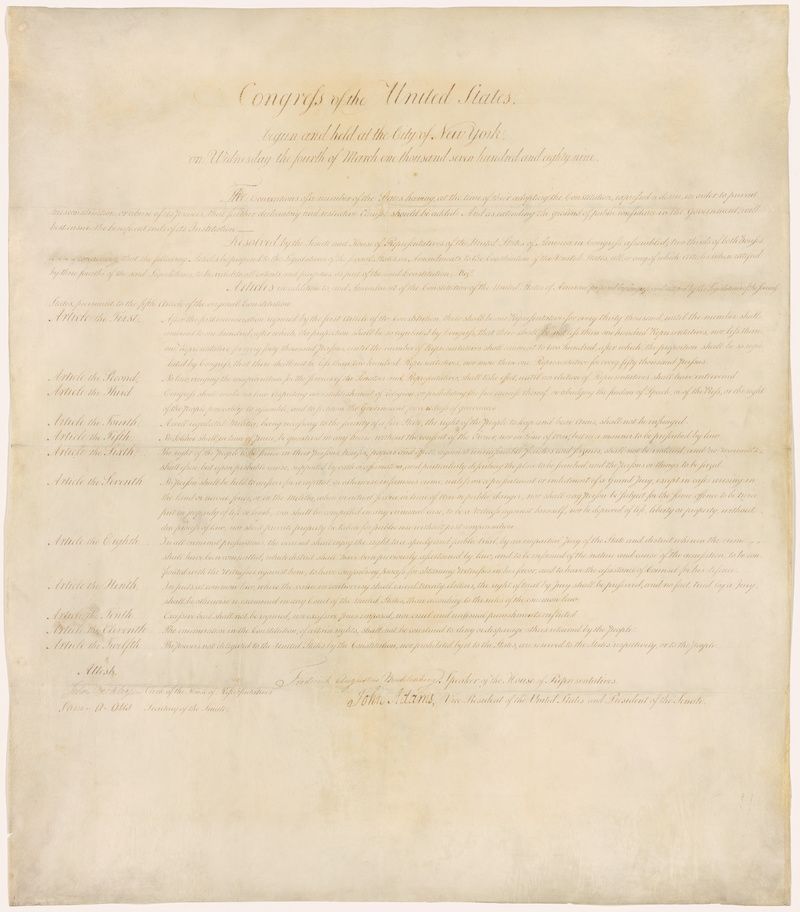

Another important item featured in the exhibition is one of the original, official copies of the Bill of Rights sent to the 13 colonies by President George Washington for approval. While it is unknown for certainty as to which copy the one on display is, scholars speculate that it is the version that was received in Pennsylvania. Written by James Madison, the Bill of Rights was made to address key issues not addressed in the Constitution including issues such as the right to freedom of speech and to keep and bear arms.

For those that pay close attention, you’ll be able to notice that there are twelve and not ten amendments listed on the document. The first two would go on to be rejected, leaving us with the current ten amendments we treasure today.

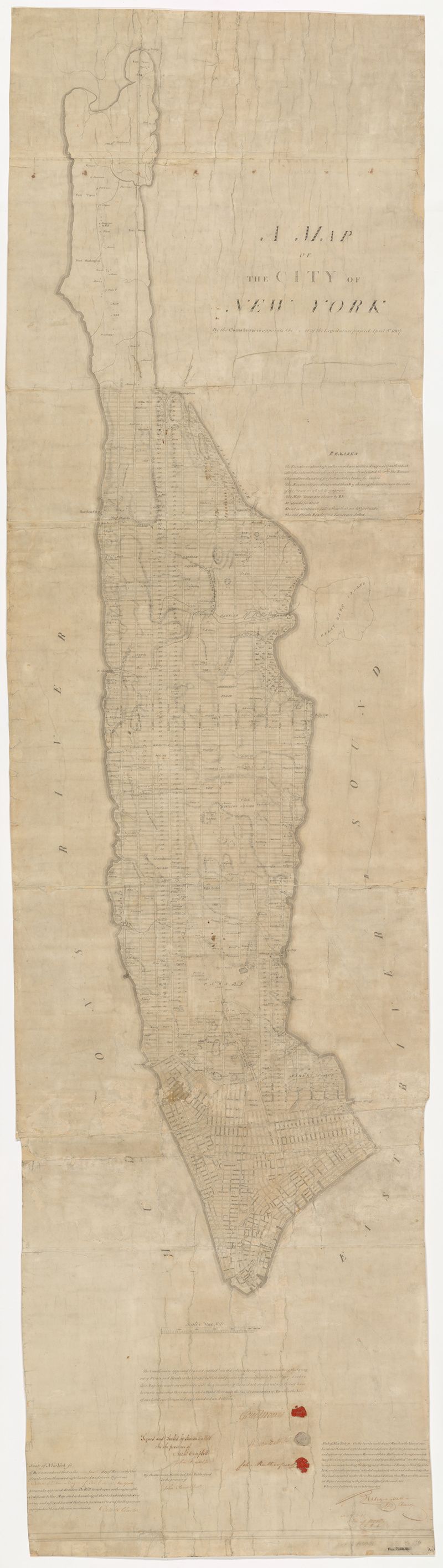

During the early 1800s, much of lower Manhattan featured a conglomeration of disjointed, winding, and uneven streets built around private land and natural barriers. However, following a mass population boom in New York City from 1790 to 1810, three commissioners set out to create a plan to better regulate the anticipated northward growth in Manhattan. As one of the three original manuscript versions of the 1811 plan, this map is a reminder of what New York City might have looked like.

While examining the map, there are key similarities and differences in comparison to the layout of Manhattan we have today. Interestingly, the 1811 version features an early version of the grid system found throughout much of modern Manhattan. However, key differences that firmly separate this map include the absence of Central Park and the absence of any grid north of 155th Street. While the map’s proposed plan was not well received by everyone, this map highlights the coming urbanization set for the future of New York City. This Commissioner’s Map is different than the version you can view at the Library of Congress.

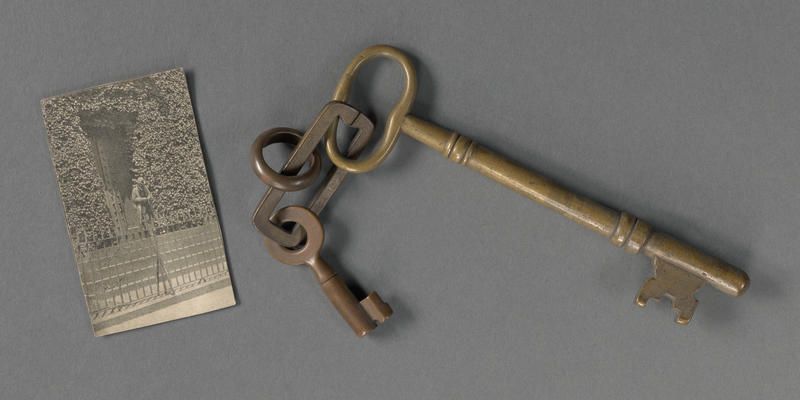

One of the fascinating secrets of the NYPL’s Stephen Schwarzman building is that it is built atop the former Croton Reservoir that used to stand in what became Bryant Park. The original foundations of the reservoir can still be seen inside the library. Getting fresh and clean water to New York City was a major challenge in the early 19th century as the city rapidly expanded. The solution to the city’s water needs was the Old Croton Aqueduct. Construction started on this water transportation system in 1837 and water first flowed through it in 1842. The aqueduct moved water from the Croton River in upper Westchester county down into Manhattan. The water was stored in a receiving reservoir which was located where the Great Lawn of Central Park is now, and was distributed from a reservoir at the current site of the Schwarzman building. That reservoir was known as the Croton Reservoir.

The Croton Reservoir held 20 million gallons of water within its walls which stood 50-feet tall and 25-feet wide. Edgar Allan Poe frequently walked atop the reservoir walls to enjoy the view they offered of the city. When it became obsolete in the 1890s, it was torn down to make way for the new library building. It took two years and some 500 workers to dismantle the reservoir. The Croton Reservoir key was gifted to the NYPL from the architects of the building, Carrère and Hastings and are on display in the Polonsky Exhibition.

We’ve all heard the tales of Winnie-the Pooh and his friends Eeyore, Tigger, Kanga, Piglet, and Roo but you might not have known that the stories were inspired by a collection of toys owned by author A.A. Milne’s young son Christopher Robin. For his first birthday in 1921, Christopher was gifted a stuffed teddy bear from a Harrods department store in London that would later be christened as Winnie-the Pooh. Over the years, Christopher’s collection of stuffed animals grew, coming to include all of the classic faces that now make up Milne’s whimsical childhood series.

In 1947, the toys — minus Roo who was lost one day in an apple orchard — were brought over to the United States and remained with Milne’s American publisher E.P. Dutton until 1987. Afterward, the toys were donated to the New York Public Library, with Christopher requesting that they be placed on display as much as possible so that everyone, but especially children, could enjoy the warmth and laughter they had brought him.

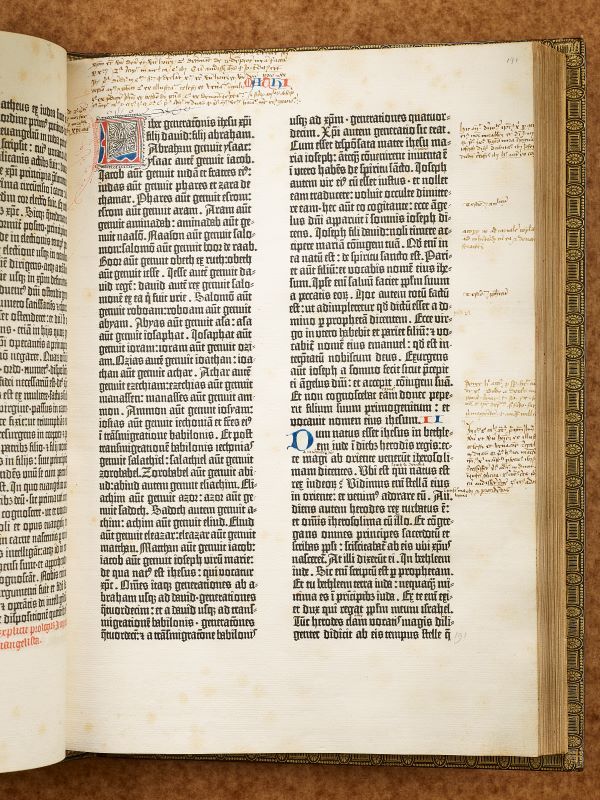

As the first sustainable book printed in Europe using mass-produced moveable metal type, the Gutenberg Bible marked a turning point in the world of print and communication. First printed in 1455 by goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz in what is now present-day Germany, the Bible’s usage of moveable metal, oil-based printing, and creation in a mechanical printing press was revolutionary. After its release, a wave in the mass production of identical texts would spread across the Western world. This in turn helped to spark the codification of grammar and syntax in language as more individuals became literate. Moreover, the Gutenberg Bible is celebrated for its aesthetic qualities, featuring beautifully rubricated initial letters in the typical style of Gothic German scribes.

Today, forty-nine copies of the Gutenberg Bible survive. The version of the Bible on display was acquired in 1847 by collector and New York Public Library founder James Lenox and was the first iteration brought to the Americas. As legend has it, Lenox’s agent instructed Custom House workers to remove their hats in respect upon seeing the Bible.

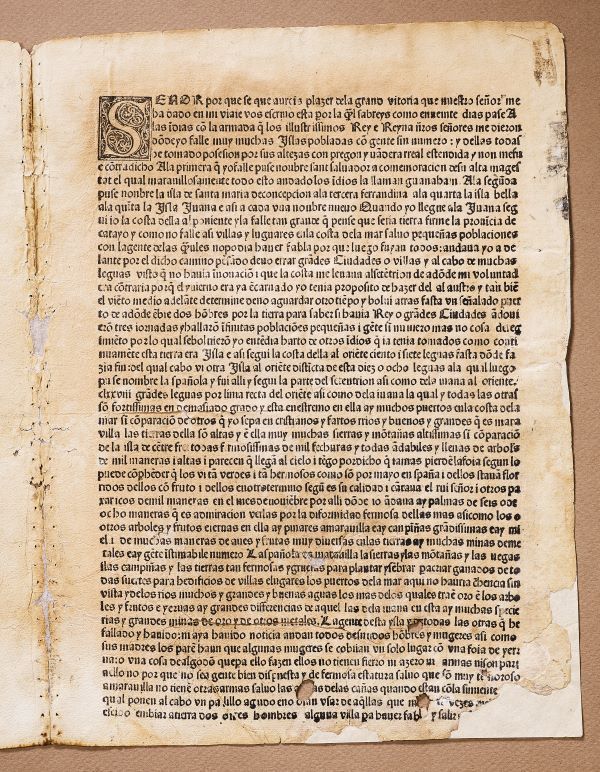

During his initial voyage to America in 1493, Christopher Columbus extensively recounted his experiences in a series of letters, one of which was addressed to Luis de Santangel, Treasurer of Aragon. Though the original handwritten letter no longer exists, the Polonsky Exhibition features the only known surviving copy of the letter’s first printed edition, which was disseminated across Europe and gave the continent’s people their first view into the world of the Americas.

The letter features detailed descriptions of the New World’s abundance of resources and Columbus’ interactions with the native populations. In examining the start of the letter, Columbus’ distorted worldview is placed on full display. He writes that as he placed down the royal Spanish flag, “no me fue contradicho,” translating to “without opposition.” Immediately, this line implicates the native populations as having been receptive and understanding of Columbus’s actions and control, a fact we know today as not having been true. In the end, at the same time as Columbus’s letter represents the coming of a prosperous era for the Spanish Empire and European conquest, it also serves as the start for the tragic end of many ancient civilizations in the Americas.

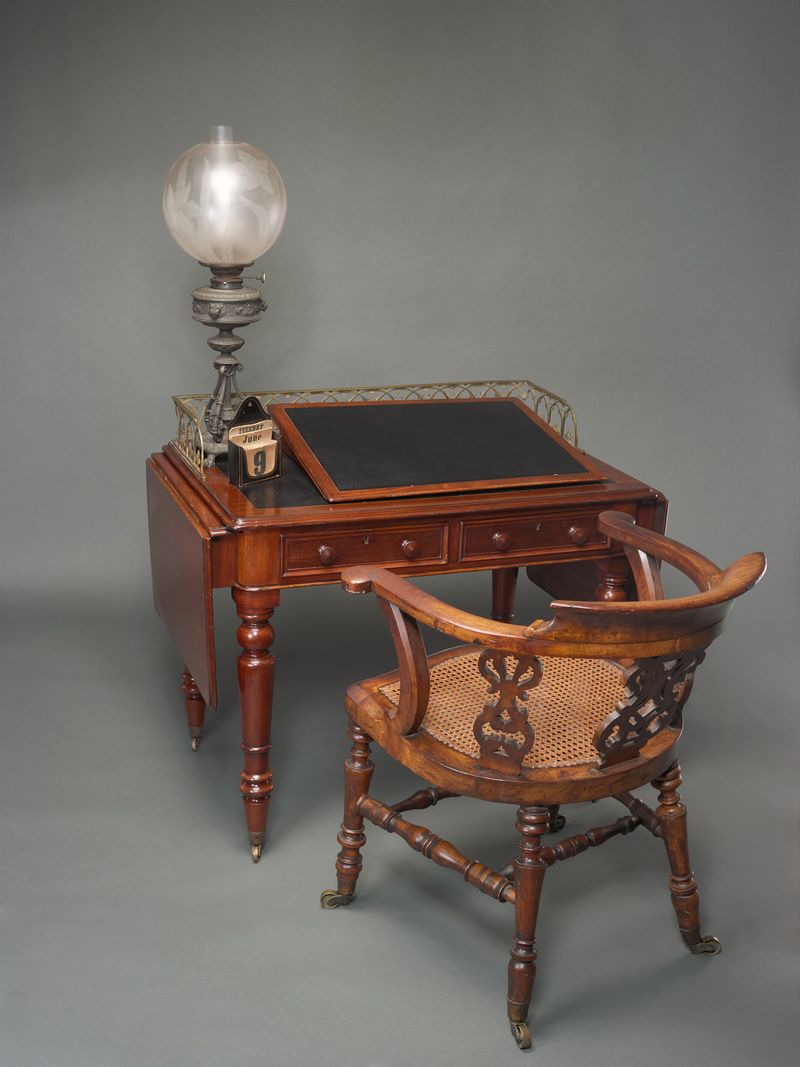

Today, Charles Dickens is regarded as one of the most influential 19th century British writers for his classic novels A Christmas Carol and A Tale of Two Cities. As an ode to Dickens’ literary genius, the Polonsky Exhibition will display one of the desks, writing slopes, lamps, desk calendars, and chairs used by him throughout his lifetime. Beautifully designed with mahogany wood and leather, Dickens’s desk once resided at Gad’s Hill Place, the author’s primary residence during the last decade of his life. Upon careful examination of the desk, a calendar flipped to June 9th can be seen standing upon it — with this marking the day when Dickens passed. Along with the desk and calendar, Dickens writing slope — which he used to craft more than 15,000 letters — and lamp were also located in Gad’s Hill Place.

Made of wood and cane with metal casters, Dickens’ chair was first located in his office at Households Words, the weekly magazine he served as an editor for in the 1850s, before being moved to his home. It is suspected that Dickens most likely drafted part of his novel Hard Times while seated in the chair. However, there is one element of the chair that is not original, with this being the canning along the seat. On October 11, 1940, Dickens’ desk and chair were featured in the formal dedication of the NYPL’s Berg Collection and new reading room. While attending the event, then New York City Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia chose to sit in the chair, desiring to feel what it would be like to be Dickens. Unfortunately, worn down from old age, the chair was unable to support the mayor’s weight and he broke right through its canning.

Tucked inside a gleaming glass container is a walking stick owned by Virginia Woolf — considered by many to be one of the greatest modernist writers of the 20th century. Having written classics like To the Lighthouse and A Room Of One’s Own, Woolf’s literary legacy carries on to today, with the New York Public Library holding the largest collection of the author’s manuscripts and letters in the world. Suffering from several ailments throughout her life, including a suspected case of bipolar disorder, Woolf was often found using a cane to support herself as she walked.

Following the start of World War II, Woolf’s mental health began to decline, indicated by the increased focus on death in her diary writings. This would come to a head on March 28, 1941, when while walking along the River Ouse, Woolf drowned herself by filling her overcoat pockets with stones. On display in accompaniment with the cane is a letter from Woolf’s husband Leonard to their friend Vita Sackville-West, written on the day she died. As Leonard laments, “[Virginia] has been really very ill these last weeks & was terrified that she was going mad again. It was I suppose the strain of the war and finishing her book. I think she has drowned herself, as I found her stick floating in the water. But we have not yet found the body.” Woolf’s corpse would eventually be recovered on April 18.

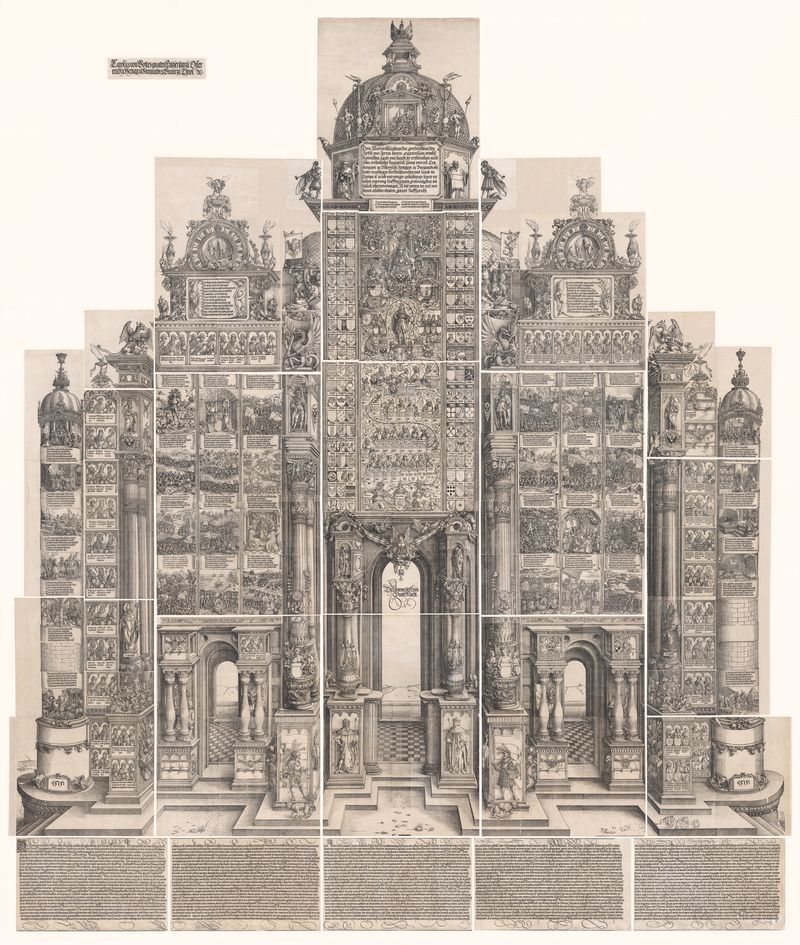

Aiming to draw support for his regime and instill fear in the hearts of his enemies, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian commissioned the Triumphal Arch — a woodcut print chronicling his ancestry, lands, accomplishments, deeds, talents, and interests. Created mainly by Albrecht Durer, the Triumphal Arch is one of the largest prints ever produced, having been created on 36 large sheets of paper from 195 separate woodblocks.

Throughout the piece, some of the most important iconographic symbols include busts of Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great to demonstrate Maximilian’s illustrious lineage and shields with the coats of arms of Stabius, Kolderer, and Durer — three of the principal architects and creators of the print. First printed in 1517, two separate editions were reprinted after. The version of Triumphal Arch on display is from the third and last edition.

What we know today as a typical book wasn’t always how they looked. During the medieval period between the 13th and 16th centuries, European monks, clergymen, and aristocrats often carried with them small portable girdle books. Made with a large piece of leather knotted at one end, girdle books were often tucked into the belt, allowing for easy transport.

Breviarium is one such book, having been owned by Brother Sebaldus, prior to the Benedictine monastery in Kastl, now Germany. As a breviary book used for praying the canonical hours, Brevarium was modest in nature featuring very little in its design. What stands out the most from the book is a series of four hand-colored woodcuts pasted into the interior.

Other items not to miss at The Polonsky Exhibition include a Berliner Gram-O-Phone, an Underwood & Underwood photography Perfescope for viewing stereograph images, a ballet flat by Coco Chanel, the umbrella belonging to Mary Poppins author P.L. Travers, Shakespeare’s First Folio and so many more. The Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library’s Treasures’ is free but requires advance ticketing.

Next, check out The Top 10 Secrets Of The New York Public Library At 42nd Street!

Subscribe to our newsletter