Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Not to be confused with the London neighborhood of the same name, SoHo in Manhattan is known today for upscale shopping and trendy restaurants, but it wasn’t always that way. SoHo—which stands for South of Houston Street—has gone through many transformations over the centuries and still holds its fair share of secrets. From the neighborhood’s past as the city’s red-light district to an extremely valuable piece of real estate filled with 280,000 pounds of dirt, here are nine of the most fascinating secrets of SoHo.

In the mid-1800s, long before SoHo became a bohemian artist enclave, it was New York City’s most prominent red-light district. At the time, Broadway was a major shopping thoroughfare (much like it is today), and brothels started popping up on the side streets leading off it.

Guidebooks were published offering gentlemen suggestions on the best (and worst) houses of ill repute. The Gentlemen’s Companion, published anonymously in 1870, refers to Greene Street as “a complete sink of iniquity” but recommends an establishment at 84 W. Houston Street, where “Everything here is arranged in the first style, while the bewitching smiles of the fairy-like creatures who devote themselves to the services of Cupid are unrivaled by any of the fine ladies who walk Broadway in silks and satins new.”

There may be newer, trendier bars in SoHo, but when you want to immerse yourself in history, you can belly up to the bar at the Ear Inn, which still feels pleasantly divey. It was originally built in 1817 by an African American Revolutionary War hero named James Brown, who used the ground floor as a tobacco shop and lived upstairs. Brown’s success in the tobacco industry led him to purchase a townhouse down the street from George Washington’s Richmond Hill Estate, where John Adams and Aaron Burr later lived.

In 1890, it became a saloon popular with longshoremen and sailors, one of whom lived upstairs and was killed by a car. Rumor has it his ghost still haunts the building. During Prohibition, it became a speakeasy and brothel. It reopened as a bar after Prohibition ended and was designated a New York City landmark in 1969. In the 1970s, the current owners called it The Ear Inn to avoid the Landmark Commission’s lengthy review of new signage; they covered up parts of the long-standing neon “BAR” sign so that it read “EAR.”

Did you know that SoHo is home to the world’s largest concentration of cast-iron buildings? In the mid- to late-1800s, cast iron was used to construct and decorate hundreds of buildings. It had a few major advantages over other building methods: it was faster, less expensive, and easier to replicate than stone or brick. These buildings also often feature fluted columns or ornate decorative elements.

SoHo’s cast-iron architecture came under threat in the mid-20th century when Robert Moses proposed plans for the Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have cut right through the neighborhood. Fortunately, the plan was nixed and Soho’s cast-iron buildings were saved. Thanks to the preservationist group Friends of Cast Iron Architecture, much of the area was designated a historic district by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1973. The SoHo-Cast Iron Historic District was extended in 2010 and encompasses 26 blocks and around 500 buildings.

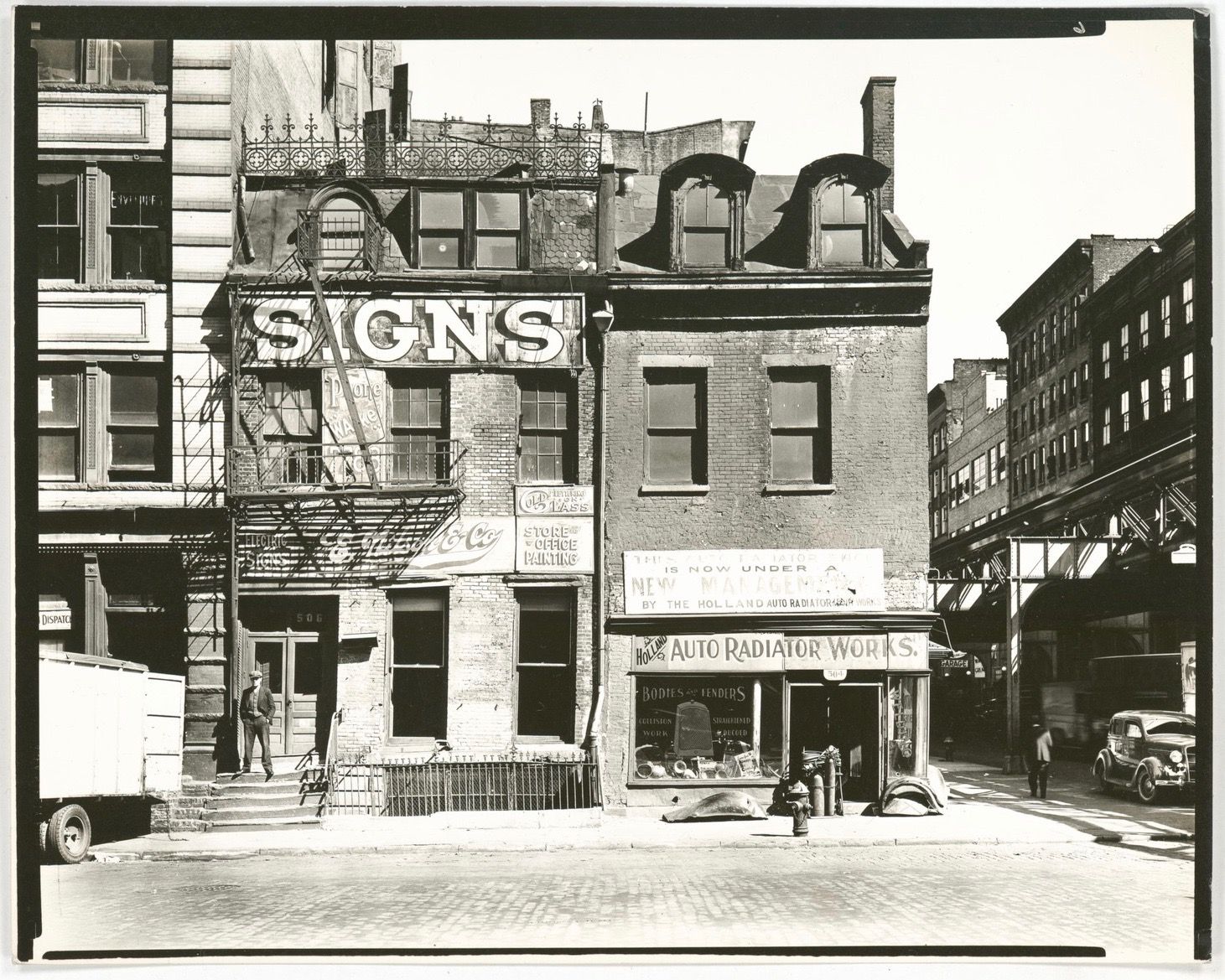

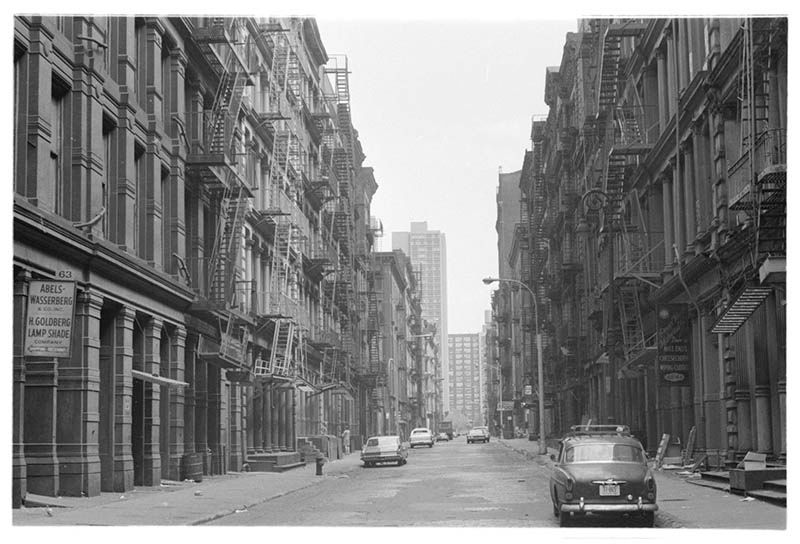

In the early 1900s, the aforementioned brothels and speakeasies began to drive out the well-to-do New Yorkers, leaving this formerly thriving commercial and entertainment area neglected. After World War II, many of the textile factories that had set up shop here in the 1800s moved to the South, leaving huge industrial buildings vacant. Many storefronts and buildings remained abandoned for decades, while others were replaced by warehouses, printing plants, and parking lots, leading to a decline in the area which would empty out at night. By the 1950s, some started calling SoHo “Hell’s Hundred Acres.”

The abundance of spacious lofts and cheap rents started attracting artists like Gordon Matta-Clark, Donald Judd, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Marilyn Minter to the neighborhood. In the early 1970s, many artists illegally lived in the old warehouses, which weren’t zoned for residential use and often lacked basic amenities like plumbing, heat, and electricity. According to the New York Times, “Artists were required by the city to post warning signs on the exterior of these buildings that read A.I.R. — Artist in Residence — so if there were a fire, the fire department would know to rescue them.”

The five-story cast-iron building at 101 Spring Street preserves a bit of 1970s SoHo when the neighborhood was full of artist studios. Donald Judd, whose minimalist art can be seen at MoMA and other art museums around the U.S., purchased the 1870 building in 1968 and used it as his home and studio before deciding he needed more space. He then moved to Marfa, Texas, where he established the Chinati Foundation on an old army base.

The Judd Foundation maintains the home and studio, which was restored in 2010 and is open for guided tours. Tickets must be booked online in advance and proof of vaccination must be shown.

Yes, you read that right. The New York Earth Room is an installation by land artist Walter De Maria. Described as “an interior earth sculpture” by the Dia Art Foundation, the arts organization that commissioned it, It covers 3,600 square feet of floor space in a unit at 141 Wooster Street. It was installed in 1977 when the neighborhood was full of cheap warehouses and lofts, but imagine how valuable that real estate must be now!

De Maria also has a permanent installation called The Broken Kilometer at 393 West Broadway. It’s made of 500 solid brass rods that each measure two meters in length evenly spaced in rows on the floor of the gallery space. If placed end to end, the rods would measure exactly one kilometer (3,280 feet).

Film buffs interested in arthouse cinema and foreign films know that Film Forum is one of the city’s best independent cinemas, but many may not know that it’s also the city’s only autonomous nonprofit cinema. When it opened in 1970, it was located in a screening space with just 50 folding chairs on Vandam Street, but it is now housed in a cinema with four screens and nearly 500 seats built in 1989 on W. Houston Street. While cinemas are shutting down all over the U.S. Film Forum is going strong with up to 250,000 annual admissions and 6,500+ members.

Film Forum runs two different film programs: one focused on theatrical premieres of American indie films and another focused on foreign art films such as the 1960 French New Wave classic Breathless by Jean-Luc Godard. It also shows foreign and American classics, genre works, and retrospectives dedicated to award-winning directors.

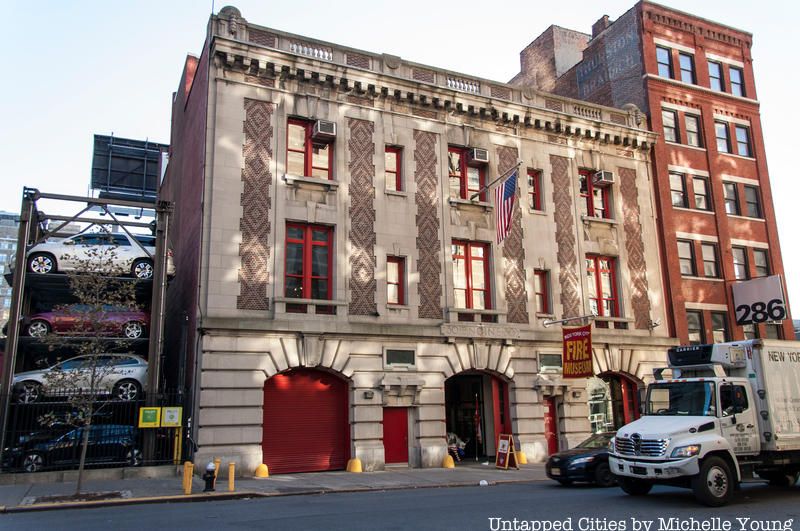

The beautiful Beaux-Arts fire station built in 1904 on Spring Street, which once housed Engine Company No. 30, is now home to the New York City Fire Museum. With over 10,000 objects, the museum holds one of the world’s largest collections of fire-related artifacts. The museum traces the history of firefighting in New York, from the colonial days of Dutch New Amsterdam to the present and telling the story of its evolution from a volunteer fire brigade to a paid municipal department. You can see firefighting tools from the 1700s to the present, including highlights such as horse-drawn carriages, pumps, uniforms, and elaborately decorated fire shields.

There’s also a special memorial exhibit dedicated to the FDNY heroes who lost their lives during 9/11. One of the most remarkable things to see is a Nikon camera from the FDNY photo team that was lost and later recovered with its memory card intact. The photos, which were taken after the first plane hit the World Trade Center, have been framed and hung up in this section of the museum.

Seen from the street, La Esquina looks like a casual Mexican diner. But book a table at the brasserie and you’ll be led into an unmarked entrance through the kitchen into a dimly lit dining room where New Yorkers sip margaritas and eat upscale Mexican street food. The vibe is perfect for a date night, with dark wooden tables, blue and white mosaics, and candles dripping wax.

But that’s not the only hidden restaurant in SoHo—there’s also a secret après ski fondue chalet inside Café Select. You’ll have to walk through a door labeled “No entry, employees only” to go through the kitchen in order to access the ski chalet. Once inside, you can feast on fondue and hot mulled wine in a space that will transport you to Switzerland, if only in your imagination.

A petition with nearly 1,000 signatures is going around with the goal of designating the area around Lafayette and Centre Streets as Little Paris. Started by Léa and Marianne Perret of Coucou French Classes, the push for an official Little Paris in New York is meant to acknowledge the large concentration of French businesses in the area. In the span of a few blocks, you can buy French pastries at Maman, sip natural wine at La Compagnie des Vins Surnaturels, shop for books and art at the lifestyle shop Clic, and take French lessons at Coucou French Classes.

The SoHo/Paris connection isn’t new, but a revival. In the late 1800s, this area was a thriving quartier français. Indeed, Lafayette Street is named for General Lafayette, who fought in the American Revolutionary War. The old Police Headquarters Building on Centre Street was modeled on Paris’s Hôtel de Ville. An 1879 issue of Scribner’s Monthly notes, “the people are nearly all French. French too is the language of the signs over the doors and in the windows.”

Next, check outthe secrets of Greenwich Village and secrets of the East Village.

Subscribe to our newsletter