✨You Can Touch the Times Square New Year's Eve Ball!

Find out how you can take home a piece of the old New Year's Eve ball!

While most New Yorkers today may immediately point to Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall, or the Bowery Ballroom as New York City’s historic music venues, one that may not come to mind is Fillmore East, a rock venue on Second Avenue near East 6th Street in the East Village.

The site has changed ownership many times, starting as a Yiddish theater and movie theater, then a number of music venues, then a gay club. But for the three years that it was Fillmore East, rock and roll (as well as other genres) flourished in the city. Tickets would never cost more than $5.50, and some of the greatest music legends such as Jimi Hendrix and Frank Zappa performed to enthusiastic audiences. Here are the top 10 secrets of Fillmore East, inspired by Frank Mastropolo’s book Fillmore East: The Venue That Changed Rock Music Forever.

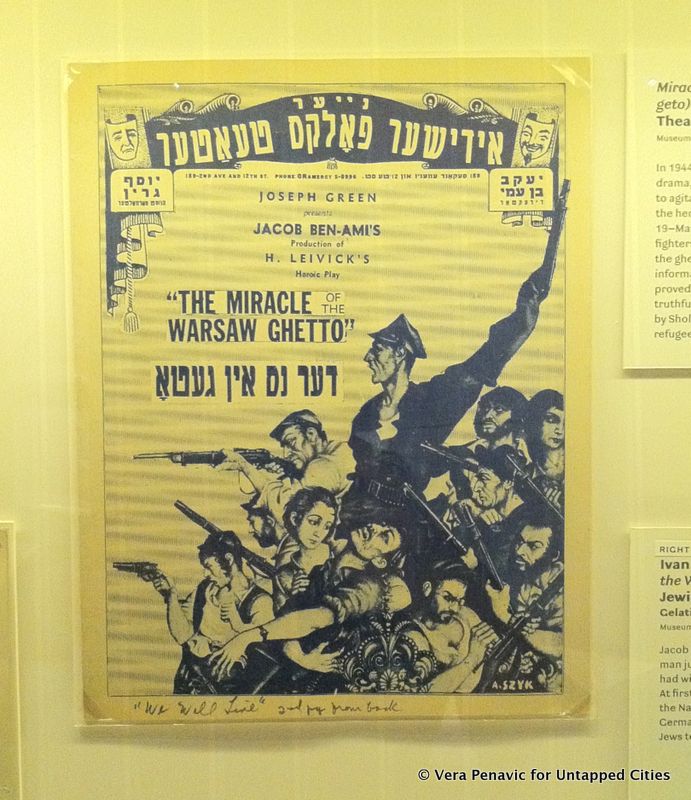

The theater at 105 Second Avenue that would later become Fillmore East was originally built as a Yiddish theater. Constructed in 1925-26, it was designed in the Medieval Revival style by Harrison Wiseman, and independently operated as the Commodore Theater. The Commodore was one of the more popular theaters in what was known as the Yiddish Theatre District, or the Jewish Rialto, where dozens of theaters would host performances of Yiddish plays by great Yiddish authors as well as Shakespeare and classic plays in translation.

The Yiddish Theatre District was centered around Second Avenue, but extended all the way to Avenue B. The district peaked around World War One, when many journalists considered it the best place to see theater in the city. The first Yiddish theater productions started in the late 1880s in New York’s lost Little Germany neighborhood around the present-day East Village. It wasn’t until 1903 that the Grand Theatre opened, putting on translated versions of classic plays, musicals, and vaudeville. George and Ira Gershwin, as well as Irving Berlin, grew up in the center of the district. In addition to theaters, which put on around 20 to 30 shows per night, the area had everything from photography studios to music stores to restaurants.

From 1965 to 1968, the space was known as the Village Theatre, hosting many legendary events comparable to Fillmore East’s. The theater opened with a performance by Donovan, and it was where Timothy Leary would lead weekly psychedelic lectures. The run-down Village Theatre hosted notable performances by jazz greats John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, Nina Simone, Frank Zappa, and even Allen Ginsberg.

When Leary departed the space, Andy Warhol considered taking it over. Warhol considered using the space to start his own religion and set up a new band, the Velvet Underground, which he managed. The rock band was fronted by Lou Reed, and they inspired and pioneered experimental, punk rock, and new wave music. They also served as the house band at Warhol’s art studio the Factory. Warhol eventually passed on the opportunity.

Visit performance sites, former homes, recording studios, and more locations integral to the rise of this rock band and NYC's avant-garde music scene of the 1960s!

Untapped New York Members get 50% off tickets! Learn more.

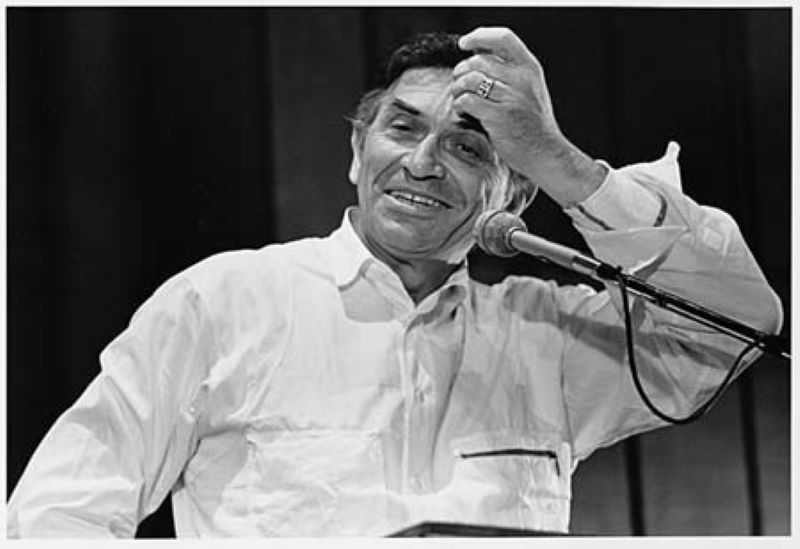

Bill Graham took over the Village Theatre in 1968 and opened “The Church of Rock and Roll” on March 8. The venue was the East Coast counterpart of the Fillmore out in San Francisco, which Graham made famous. He helped bring in and popularize performers such as the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, and Big Brother and the Holding Company. Graham regularly alternated between the East and West Coast venues, and he also owned Fillmore Records starting in 1969. Citing financial reasons and unwelcoming shifts in the music industry, Graham closed the East and West Coast venues in 1971. Graham’s journey to fame as a rock concert promoter, though, was rather fascinating.

Graham was born in Berlin in 1931 and was placed into an orphanage so that he could go to France in 1939 just before the Holocaust officially began. After the fall of France, Graham was able to make it to the U.S. as part of the One Thousand Children, who managed to flee Hitler and Europe while their parents stayed behind. Graham’s mother died at Auschwitz while he was placed in an orphanage in the Bronx. He served in the Korean War and was awarded both the Bronze Star and Purple Heart.

Fillmore East was nicknamed “The Church of Rock and Roll” due to its two-show, triple-bill concerts several nights a week. Perhaps one of the most notable performances at Fillmore East was the Allman Brothers Band’s June 27, 1971 concert, the closing night of the venue. Their explosive blues rock filled the venue for seven hours into dawn. The Allmans were sometimes called “Bill Graham’s house band” because of how many concerts they performed there. The Doors gave a crazy 1968 performance in which they played their regular collection of material one night but then came back after most of the crowd left and played again for nearly an hour.

The Grateful Dead were frequent performers at the venue as well, one night playing for hours and jamming with Duane Allman and Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac. On another night, the group dosed Graham’s can of 7-Up with LSD before going onstage. A 20-man band backed Joe Cocker one night in 1970, while that year Pink Floyd performed its album Atom Heart Mother to many first-time listeners in the U.S. Other figures who had noteworthy performances here included B.B. King, Santana, Frank Zappa, and even John Lennon.

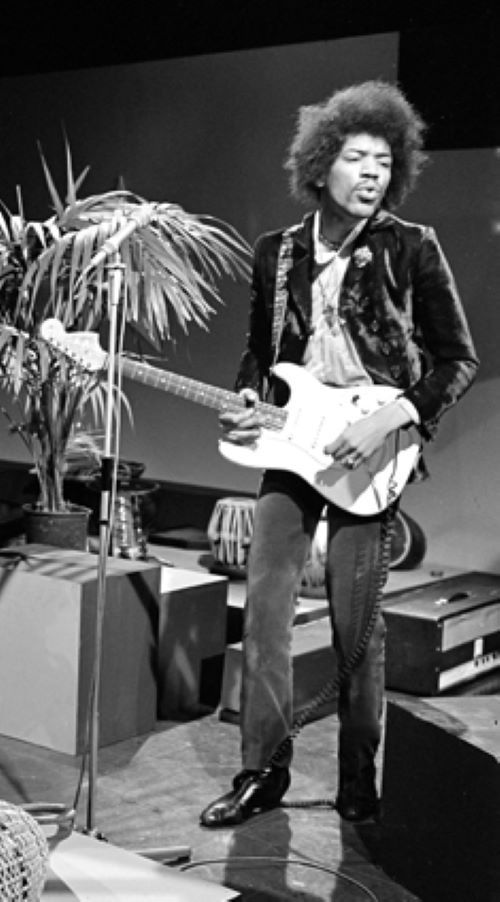

On New Years Day in 1970, Jimi Hendrix gave perhaps one of the most famous performances at the venue. But the story behind how he got the gig is perhaps just as wild as the concert itself. Hendrix had signed a deal with Ed Chalpin of studio PPX around 1965 when he first started to gain international acclaim. After becoming the leader of the Jimi Hendrix Experience, he was signed to a different contract with Track Records. Because of this, Chalpin sued him for a share of his profits. Hendrix thus gave over his next album to PPX for distribution in order to make amends. It was this conflict that ended up getting him this show, which some consider among his career highlights.

Hendrix chose to form a completely new group with Billy Cox on bass and Buddy Miles on drums, mainly because he did not want to give PPX distribution rights of Electric Ladyland. His new band played two nights at Fillmore East, December 31st, 1969, and January 1st, 1970. His album Band of Gypsys was recorded live on the January 1st show, while Live at the Fillmore East drew from both performances. Hendrix’s performance of “Machine Gun” is often recognized as one of his musical highlights, although the concerts could not compare to Woodstock a year earlier.

The Joshua Light Show, which was headed by American artist Joshua White, was an integral component of many of the venue’s shows. Many bands would perform in front of a psychedelic backdrop that incorporated “liquid light shows.” The shows took advantage of glass crystals, watercolors, film and slide projectors, and color wheels. All shows were based on four elements: projection of pure color, concrete imagery, variety of color effects, and shaping of the light.

The light show appeared on the back cover of Jimi Hendrix’s Band of Gypsies and the front cover of Iron Butterfly’s In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. The light shows also provided trippy backgrounds for Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, the Doors, Lou Reed, Ravi Shankar, and many other performers.

Inside Fillmore East was a concession stand on the balcony that sold some rather unexpected products for a concert venue. The concession stand offered fresh fruit and juices, donuts, bagels with cream cheese, and many flavors of Dannon Yogurt. There was also a slightly less exciting ground floor refreshment stand offering hot dogs, popcorn, and soda.

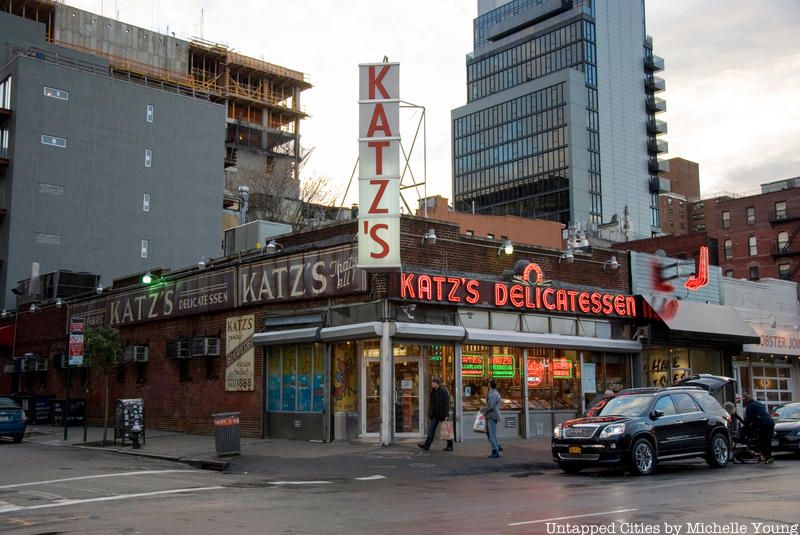

For those craving a slightly more filling meal, many would flock to Ratner’s Delicatessen next door, where Graham made himself a makeshift office. Ratner’s was a Jewish kosher deli that was often seen as the complement to Katz’s since it did not serve meat. It was known for its cheese blintzes, potato pancakes, gefilte fish, and split-pea soup.

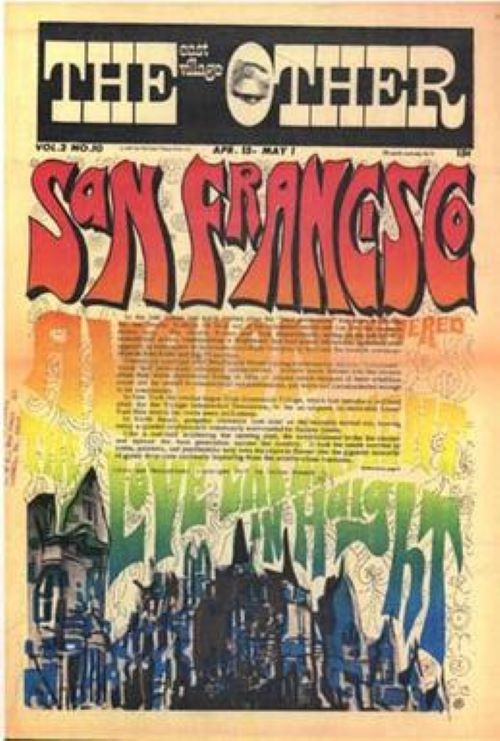

The East Village Other was a biweekly underground newspaper during the 1960s, described by The New York Times as “a New York newspaper so countercultural that it made The Village Voice look like a church circular.” It often featured comic strips by figures such as Art Spiegelman, Robert Crumb, and Kim Deitch. Many of its comics were satirical and touched on socially relevant themes—including, surprisingly, Bill Graham.

In the building upstairs from Fillmore East’s lobby were the offices for the East Village Other. Supposedly, the paper was not paying any rent. They often poked fun at Graham and would side against him in trying to make Wednesday shows free (and thus give up some of his capitalist ways). The feud continued until one day, Graham was angry about an article in the paper and threw them out of their space.

After Fillmore East closed, in came Villag East with performances of “Virgin: A New Rock Opera Concert by the Mission.” After the short-lived rock opera, there were numerous performances at the venue in 1972. In 1974, it briefly reopened as the NFE (New Fillmore East) Theatre, but Graham forced the theater to change its name to the Village East. From 1980 to 1988, the renovated venue was home to the Saint, a gay club that was heavily impacted by the AIDS crisis.

By the end of the second year, the Saint’s membership began to succumb to AIDS. The club subsequently lowered its prices and stayed open almost all year round, implementing policies such as safe sex for performers. The circular dance floor measures 5,000 square feet, and it was topped by a planetarium dome. Figures such as RuPaul performed at the Saint early in their careers. Ultimately, though, the club had to close, and the space remained rather dormant until an Apple Bank for Savings moved in. As of April 2025, it's empty again.

Today, two distinct memorials honor the Church of Rock of Roll. The first is “Bill Graham Way,” which officially designates the stretch of Second Avenue between 6th and 7th Streets. Second are the tile mosaic plaques which stud the lamppost in front of the former theater. These mixtures of jagged ceramics and broken pottery are the work of Irish-born Vietnam veteran Jim Powers, who has unofficially landmarked other lampposts throughout the East Village.

There are only a few remnants of Fillmore East, including posters and some photographs by Amalie Rothschild, who was also a Joshua Light Show member. Additionally, a green-and-gold usher jersey still remains. There’s also Graham’s cowbell, which is possibly the one that was presented to him by Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart before a January 1970 show.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Radio City Music Hall!

Subscribe to our newsletter