At the crossroads of Third Avenue and Brook Avenue in the Bronx sits a beautiful marble sculpture, an allegorical representation of “Justice” or “Lady Justice,” on the facade of the old Bronx Borough Courthouse. Today, this distinctive work of art is an icon of the Melrose neighborhood, an area that has been redeveloping in recent years thanks in part to new housing developments. The courthouse site is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a designated New York City Landmark, but it is unoccupied and lacks a historic plaque that would tell of its connections to America’s heartland and an immigrant artist.

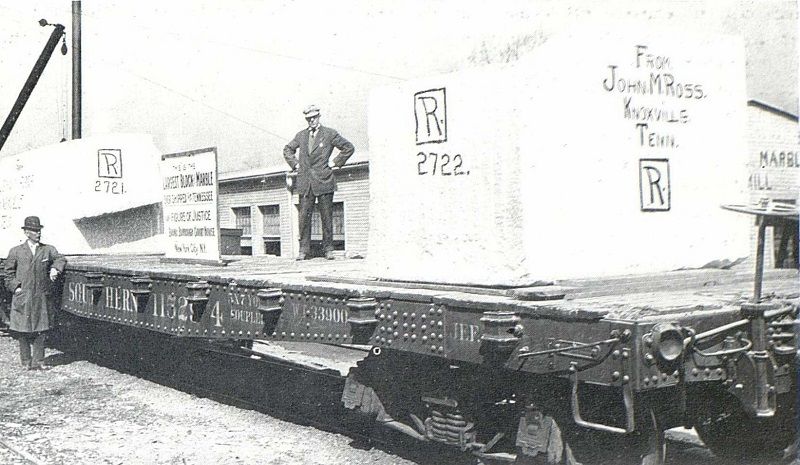

The artwork’s pink marble came from the John M. Ross quarries near Knoxville, Tennessee in 1910. A few years earlier, the firm supplied the same stone for the exterior of the Morgan Library in Manhattan, but the order for the Bronx was a record-breaker. As the sign on the photo above indicates: “This is the largest block of marble ever shipped from Tennessee – for figure of Justice, Bronx Borough Court House, New York City, N.Y.”

Stone, a trade publication, reported that the “largest block measured 8 feet, 6 inches by 8 feet by 5 feet. The other block measured 7 feet, 5 inches by 6 feet, 11 inches by 4 feet, 10 inches. The larger block is to be used for a statue of ‘Justice’ for the Bronx Court House and the smaller block is for the pedestal on which it is to stand. The total weight of the two blocks was over a hundred thousand pounds.”

Once delivered to New York, “Lady Justice” was carved according to a design by Jules Édouard Roiné, a French-American artist. The NYC Art Commission selected Roiné in February 1910 after rejecting submissions from Louis Richard, a prominent French immigrant sculptor.

At the time, Roiné was better known for medals, plaques, and similar works than for statuary of this sort. Born in France in 1856, he came to the United States in the 1880s and from then on received commissions in both countries. He had a studio at 139 East 23rd Street for several years, where he worked until he returned to his homeland in 1915 before dying the following year.

Who executed the work is unclear, but a likely choice would have been the Piccirilli Brothers, a Bronx-based Italian-American stone carving firm whose long list of projects included the New York Public Library lions, also from Tennessee marble.

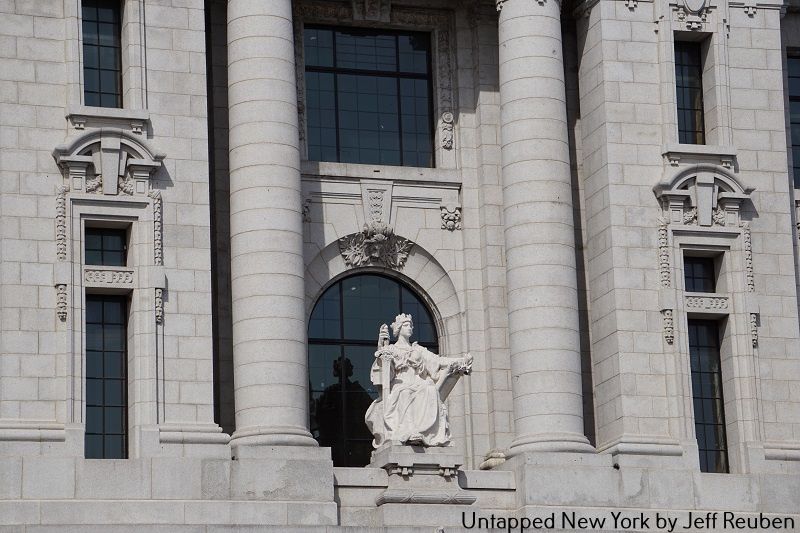

The sculpture is positioned above the courthouse’s main entrance, backed by an arched window and flanked by pairs of columns in a manner characteristic of the highly ornamented Beaux-Arts civic architecture of the period.

However, unlike the more typical justice figures who are blindfolded, standing, and holding scales, this one has her eyes open and, as a report by the Art Commission describes, “it consists of a draped seated female figure, of heroic size, with a crown of leaves in hair, supporting with right hand a large sword, and holding with left hand a book which rests on seat.”

An unblinded Lady Justice was unusual but not unprecedented. For example, a similar-looking figure is La Loi (The Law), a mid-19th century sculpture in Paris by Jean-Jacques Feuchère, which Roiné would have known.

The choice also seems to have been in sync with, if not in response to, the preferences of the Art Commission. One of the rejected designs by Louis Richard featured a blindfolded Lady Justice of which the commission suggested “that he remove the bandage from the eyes.”

Roiné’s Lady Justice proved to be a bright spot for an otherwise troubled project. Placing such an important facility next to the Third Avenue Elevated Line attracted considerable criticism and scandals, including the selection of its architect and granite supplier, which led to Borough President Louis F. Haffen’s removal from office.

The Bronx Borough Courthouse opened in 1914, massively over budget and behind schedule. The Evening Post scoffed in 1912 that due to years of delays, “the building has practically been deserted save for the lone watchman and the statue of ‘Justice’ which adorns the entrance.”

In contrast to the courthouse, Lady Justice was a relative bargain. A 1910 New York Tribune article reported that the City of New York paid $4,000 for it, about $115,000 today, which presumably included material, design, and labor.

The Bronx Borough Courthouse has been vacant since the 1970s and the subject of various unrealized proposals for its reuse. It temporarily reopened in 2015 when the non-profit organization No Longer Empty presented an art show for several months that included a drawing by artist Lady K Fever (Kathleena Howie) of Lady Justice, which was covered by construction scaffolding and netting.

The courthouse’s designation as a New York City Landmark in 1981 ensured its survival but not its revival. Plans for conversion to a charter school announced in 2017 have not come to fruition, though thanks to upgrades in the mid-2010s the sculpture and building look much better than before, as the photo below from 2014 illustrates.

But even at the site’s nadir, the community organization Nos Quedamos, which unsuccessfully sought to convert the building to community use in the early 2000s, found inspiration in Roiné’s work.

“If you look at her,” the group’s executive director, Yolanda García, told the New York Times in 2000, “she’s not standing, she’s not blindfolded, and she doesn’t have a scale. She holds a sword. She’s in The Bronx, after all. She knew she had to defend herself.”

Next, check out the new Moynihan Train Hall, which also features Tennessee marble. Contact the author at Jeff Reuben.