Insider Keen’s Steakhouse, one of the oldest restaurants in New York City

Looking to experience the culinary side of New York’s history? Look no further than these 15 classic restaurants that have been cherished by local New Yorker’s for generations, all which were founded before the turn of the 20th century. From former pipe clubs to knish bakeries, these spots offer delicious menus served with a journey into the past. So take a tour of the dishes that made the city’s food scene internationally known, and treat yourself to the delectable dishes of New York’s oldest restaurants:

1. Fraunces Tavern (1762)

Fraunces Tavern, dating back to 1762, is considered to be the oldest restaurant in the city. There is some debate as to the actual age of the building itself. While the brick house in the Financial District that would become home to the restaurant dates back to sometime between 1719 and 1722, it’s been rebuilt and renovated countless times, causing many to wonder whether it can claim to be as old and authentic as it does.

Nonetheless, what it known is that before Samuel Fraunces opened it for tavern service as the “Sign of Queen Charlotte,” it was used as a dance school and trading firm. Even General John Lamb sending a cannonball through the tavern’s wall during a scuffle with the British in 1775 did not deter the popular establishment’s business. The year after, the British captured the restaurant and forced the staff to feed their soldiers. When they were finally driven out on November 25th of 1783, General George Clinton held an honorary banquet there for George Washington, whose tooth is now on display in the upstairs museum.

The restaurant’s history from then on is incredibly varied. It housed several government offices at times, as well as a boarding house in which a famous ballerina was stabbed to death. But its significance to American independence and history never wavered. The Sons of the American Revolution was founded inside in 1883, and the building was also narrowly saved from destruction by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1900.

Truly, the fact that Fraunces Tavern still stands is a miracle of endurance. Besides the wayward cannonball, it has survived three different fires and a bombing in 1975 by a Puerto Rican paramilitary group, which killed four people inside. Today, its incredible story is documented in the museum that stands just above the restaurant. Next to the numerous landmarks of American history that occurred inside, the fact that the restaurant also serves a great brunch and specializes in fine beer and whiskey is just a bonus.

2. Ear Inn (1817)

Tucked away on the far west side of Soho, you’d never guess the backstory of the Ear Inn. In fact, despite its extensive history, this cozy beer and burger joint remained nameless until the ’70s, when the owners covered the round parts of the “B” in a lighted “Bar” sign outside, and the catchy name appeared.

The building housing the Ear Inn dates back to 1770, when it was constructed in honor of James Brown, an African soldier who resisted the British by the side of George Washington and supposedly makes an appearance in the famous painting of Washington crossing the Delaware River. From there, the Inn made good money servicing sailors a refreshing drink while stopping on their way down the Hudson River (which was only a mere five feet from the building originally). Timber found in its attic sparked rumors that this bar was built using left over lumber from the Great Fire of 1776.

Food and restaurant service began in the early 20th century. During Prohibition, the bar was converted into a speakeasy, and reopened publicly upon the passage of the 21st amendment. With nautical-themed decor and blooming flowerpots hanging outside, the Ear Inn remains a popular spot to grab a drink or a bite to eat. They’ve also adopted a “farm to table” policy, so even bar snacks are prepared with fresh, healthy ingredients.

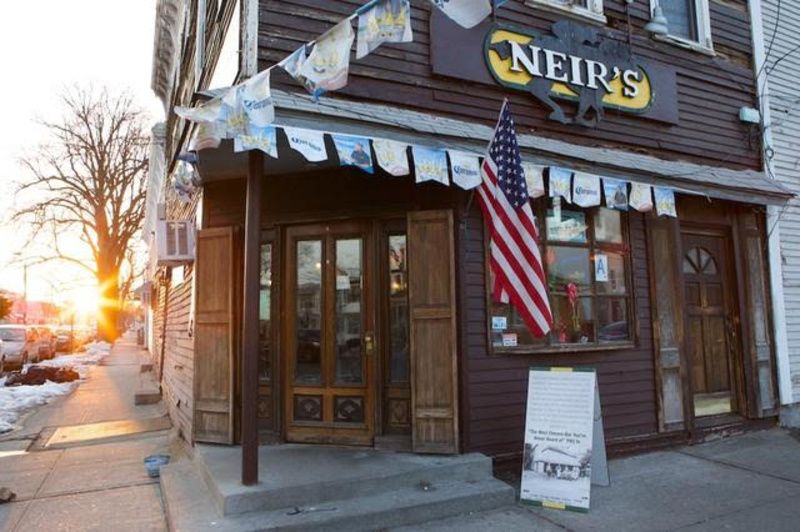

3. Neir’s Tavern (1829)

Photograph Courtesy of Neir’s Tavern

Neir’s Tavern got its start catering to gamblers at the nearby Union Course horse racing track in Woodhaven, Queens. Originally known at its opening in 1829 as the Blue Pump Room, and later as the Old Abbey, it was known as a rough and tumble hangout for the wild crowds that would frequent the races, specializing in rum. The business’ reputation changed drastically in 1898 when it was purchased by its namesake, Louis Neir, who gave it a makeover as a “social hall,” featuring a ballroom, bowling alley, and rooms for rent. While Neir’s name was forgotten when the place was resold again in 1967 and renamed the Union Course Tavern, it received a long due remodeling in 2009, and its previous name of Neir’s was restored.

While Neir’s hasn’t retained the kind of name recognition it had a century ago, it has taken on a new identity in film and TV. It was used in the 2011 action flick Tower Heist, and has been featured in Goodfellas. It’s also a favorite of several starlets: W.C. Fields famously loved the tavern, and it was apparently the spot of Mae West’s first performance.

4. Delmonico’s (1837)

When it comes to expensive meats, right up there with Wagyu is the Delmonico steak. The dish got its name from the restaurant of the same name that sits at the bottom of a Financial District canyon on Beaver Street. Delmonico’s claims to be the first fine dining restaurant in the entire country. It was opened by the Delmonico brothers in 1837 and gained a reputation as an elite establishment offering private dining rooms and the largest wine cellar in the city to those who could afford it.

Delmonico’s credits Charles Ranhofer, its executive chef during the Civil War era, with creating such American classics as baked Alaska, lobster Newburg, chicken a la Keene, and apparently eggs benedict. This last claim has incurred some controversy regarding who was responsible for the birth of the classic brunch dish. The idea, originally meant to cure a hangover, is attributed to both Ranhofer and the Waldorf Astoria chef Oscar Tschirky.

The Delmonico steak itself, originally meaning whatever the cut of the evening was in the restaurant, is now typically a boneless rib-eye, cut thick and served without brushing, a purist mentality. It’s known as a “black and red” steak, or charred on the outside but medium rare on the inside, a difficult combo for chefs to pull off. If you’re a steak lover, or even just a fan of the dishes that were born here, Delmonico’s is your perfect dining experience. Delmonico’s has been closed since 2020 as complications over ownership and its lease continue.

5. Killmeyer’s Old Bavaria Inn (1855)

Staten Island is the proud yet unlikely possessor of some of New York’s oldest, such as this hidden gem: Killmeyer’s Old Bavaria Inn. Located on Arthur Kill Road on the far side of the Island from Manhattan, Killmeyer’s was part home, part shop before it ever started tavern service, so no one is entirely sure how far it dates back. According to local author Patricia Salmon, part of the building was built in 1845, and its official date refers to its purchase ten years later by tycoon Balthazar Kreischer, who owned a brick company in the same area, of which some parts still remain. The inn got its name in 1859, when it was sold to Nicholas Killmeyer, and the ownership would stay in the family for nearly a century afterwards.

The second phase of Killmeyer’s history began after WWII, when the inn was purchased by Ken Tirado with the intention of restoring its original German character. After making a trip to Munich for some field research, Tirado returned to model Killmeyer’s on a traditional German inn, complete with classic dishes like wienerschnitzel, goulash, and, of course, hearty pints of beer.

6. Pete’s Tavern (1864)

While Pete’s may not be the absolutely oldest on this list, it is, for good reason, the oldest continually operating restaurant in New York. The atmosphere is nostalgia at its core, with black and white snapshots of the tavern through the years lining the walls. Besides serving delicious “saloon style” eats, its claim to fame is that O. Henry was once a regular.

Pete’s was a favorite spot of the short story writer between the years of 1903 and 1907, when he lived nearby, and one table on the dining floor is still marked as the place that he wrote his masterpiece of misbegotten generosity The Gift of the Magi. Perhaps hoping to tap into O. Henry’s energy, Ludwig Bemelmans also wrote the well loved children’s book Madeline while sitting in Pete’s. If you’re not inspired by the literary history, you will be by the classic dishes and lengthy cocktail list.

7. Old Homestead Steakhouse (1868)

Old Homestead is not only one of New York’s oldest, but also the longest continuously operating steakhouse in the U.S. Like many other current steakhouses in New York, this one was born in 1868, around the same time as the concept of a “chophouse” gained popularity just after the end of the Civil War. It was originally known as the Tidewater Trading Post, because the Hudson River of the time ran next to it, straight through the center of what is now Chelsea. The restaurant was purchased by Harry Sherry, who got his start working in the back as a dishwasher, and has been run by the same Sherry family for over 70 years.

Besides its impressive legacy, the Old Homestead’s other claim to fame is that it’s responsible for the first importation of Wagyu, or kobe beef to the U.S. in the ’90s. Kobe, a region of Japan native to the unique Wagyu cows, produces some of the most high priced and delicious steaks in the world, widely revered by food critics as the absolute best. To put it in perspective, a Wagyu burger from the Old Homestead will cost you $47. If you’re looking for the highest of the high quality and you don’t mind a little splurge, the Old Homestead has had your back for over 150 years.

8. Landmark Tavern (1868)

In 1868, Patrick Henry Carley opened the Landmark Tavern, an Irish waterfront saloon along the shores of the Hudson River. Carley and his wife designed their new saloon to serve as a home for their children on the second and third floors. However, during Prohibition, they were forced to turn the third floor into a speakeasy. The bar was a regular hangout for a Hell’s Kitchen gang called the Westies. The tavern is also supposedly haunted — the ghosts of George Raft, a Confederate soldier, and an Irish immigrant girl have been seen over the years.

The Landmark Tavern still retains its classic old New York charm. Located on 11th Avenue and West 46th Street in Hell’s Kitchen, the tavern still serves up classics like shepherds pie, bangers and mash, and corned beef and cabbage, but has more recently introduced items like duck confit, lobster ravioli, and Asian vegetable spring rolls.

9. Gage and Tollner (1879)

Famed for its chandeliers and red-cushioned seats, Gage and Tollner opened in 1879 on Fulton Street, Brooklyn. Until 2004, the restaurant served its prized seafood and chops, including an extensive raw bar menu. However, Gage and Tollner closed in 2004, and a T.G.I. Friday’s moved into the space. Then came an Arby’s. Then came a costume jewelry store. And New Yorkers for the most part forgot about the restaurant’s antique fixtures, which had been replaced by modern lighting and decor.

However, in 2018, a crowdfunding initiative was set up to restore the restaurant to its former glory. In the same space, the crowdfunding organizers envisioned a “70-seat dining room, a 40-seat bar area, two combinable private dining rooms seating up to 60, and a separate 30-seat tropical cocktail bar upstairs.” After three years of construction and planning, Gage and Tollner officially reopened on April 15, 2021. All the brass and woodwork stayed because the whole 1892 interior has landmark protection, but many of the antique relics were reintroduced or remodeled — even its graceful chandeliers, which now are electric.

10. Whitehorse Tavern (1880)

As spelled out clearly on its website, the Whitehorse Tavern claims the title of the second oldest pub in New York, at 139 years old. It got its start in the mid 19th century, catering to Irish communities in the Village. But it didn’t gain a real name for itself until the 1930s, when the Whitehorse was swept up in the counter culture movement, and became a hub of leftist politics, writer’s circles, and cutting edge music. Over the years, its lineup of regulars has included musicians Bob Dylan and Mary Travers of Peter, Paul, and Mary.

As the favorite of writers like Jack Kerouac, James Baldwin, Norman Mailer, William Styron, Allen Ginsburg, and more, the Whitehorse, then known as “the Horse,” has a special place in the Village’s literary tradition. Graffiti in the bathroom reading “GO HOME JACK” is testimony to the many times Jack Kerouac was kicked out for drunken behavior. A portrait also hangs over the favorite seat of Dylan Thomas, who may have spent his last hours at the bar in 1953. The iconic culture paper, The Village Voice, also traces its roots back to conversations at the bar of the Whitehorse.

The tavern’s unique historical and literary significance became a case study in Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities. In 1969, it was awarded a historic landmark designation, which has saved it from alteration several times. In 2019 it reopened under new ownership with a new renovation. Today, its virtue still lies in adherence to its history, with a nostalgically-styled bar and mementos of the old days lining the walls.

11. P.J. Clarke’s (1884)

Some restaurants may be older than this homey burger bar, but few have as impressive a lineup of famous diners as P.J. Clarke’s. Its website quotes Nat King Cole, who called its burger “the Cadillac of burgers,” and says that “Buddy Holly proposed to his wife here five hours after they met.”

The pub got its start in 1884 serving beer to Irish immigrants, and became even more popular during Prohibition when it illegally brewed and imported gin and scotch. From then on, P.J.’s wormed its way into the hearts of multiple stars, like Frank Sinatra, Jackie O, Peter O’Toole, Elizabeth Taylor, and Johnny Mercer. (The bar is almost certainly the inspiration for the boozy ballad “One for My Baby,” which Mercer wrote on the back of a napkin in the restaurant.) Author Charles Jackson also penned The Lost Weekend while dining here, and the motion picture on which it was based was filmed on a Hollywood set modeled after P.J. Clarke’s. It was also a filming location for Mad Men and Annie Hall.

When the property was finally sold by the Lavezzos in 1967, a 99-year leaseback was included. So, go try the burger loved around Hollywood, lest you regret it come 2066 when the lease expires.

12. Keen’s Steakhouse (1885)

The walls of Keen’s Steakhouse are covered in old playbills and theater memorabilia. That’s because when this high end steakhouse and oyster establishment opened in 1885 under the managerial leadership of its namesake, Albert Keen, it was mainly used by actors and performers from next door Garrick Theatre as a place to freshen up between acts. The actors starring in Abraham Lincoln’s last show were once among them, hence a wall of Lincoln memorabilia that includes the final show’s playbill on one wall of the restaurant.

The other unusual decor that will catch diners’ eyes are the long clay pipes that completely cover the ceiling of every room of the restaurant. During the turn of the century, Keen’s became a Pipe Club, or an inn in which travelers could check their pipes, a business niche that originated because clay pipes were too fragile to be carried on long journeys on horseback. Members could stop by Keen’s for a smoke, and then have their personal pipe kept behind the desk. Each pipe now hanging on the wall represents a member, including Teddy Roosevelt, Buffalo Bill, Babe Ruth, and Albert Einstein. Broken pipes signify a deceased member, as the stem of a pipe was broken when its designated owner passed away.

Among Keen’s many moose-head and chandelier clad rooms is one known as the “Ladies Room.” Keen’s was originally a male only club, up until 1905, when glamorous actress Lillie Langtry won her lawsuit against Keen’s, forcing them to designate a room for female members.

Nowadays, Keen’s provides a gilded, old-world dining experience. Their mutton chops are especially renowned, and were praised by James Beard as putting “everyday chops momentarily in the pale.” Come for the flavor, stay to pick out the well known names on the pipes that line the wall.

13. Peter Luger Steakhouse (1887)

This well respected Brooklyn steakhouse got its reputation from both its delectable cuts and its no credit card policy. After you’ve finished a signature plate of Peter Luger’s steak and potatoes, the payment options include cash and a “house account,” essentially an in-restaurant payment plan. You might think this would dissuade today’s customers, but the house account lists hold over 90,000 regulars, so you can be sure the food is well worth the cash you’ll have to take out.

Peter Luger opened in 1887 as the modest “Carl Luger’s Café, Billiards and Bowling Alley.” When Carl passed away, the restaurant was auctioned off to Sol Forman, who owned a silverware store across the street and consumed at least two of the cafe’s steaks every single day. The restaurant has been in the same family ever since, and guarantees the finest in steak production, with all meat served USDA prime and dry-aged on site.

14. Katz’s Delicatessen (1888)

Anyone who’s been around the Lower East Side has either seen, or heard of Katz’s Delicatessen. That’s not to mention its roles in multiple films, most notably When Harry Met Sally, but also Across the Universe, Donnie Brasco, and Enchanted. Silver screen appearances aside, they still make what is renowned as the best pastrami sandwich in the city.

Back in 1888, the Jewish run diner was “Iceland Brothers,” until it merged with the Katz family and became “Iceland and Katz,” and then just “Katz’s” when the latter bought the Icelands out. Its original location on Ludlow was next to the National Theatre, where it gained the business of Yiddish actors on Friday nights because most other nearby Jewish delis were closed for Shabbat. Katz’s look today is due to the influx of money it received from a WWII campaign it launched called “send a salami to your boy in the army,” which was later used in the 1952 film At War with the Army. Its first film role was in the Frank Sinatra film Contract on Cherry Street, and from then on, it’s been the enduring icon of Jewish New York delis and quality sandwiches alike.

15. Old Town Bar (1892)

An icon of the Prohibition era, Old Town Bar has maintained its name recognition in movies and TV. Located near Union Square on 17th Street, the bar was originally known as “Viemeisters” when it opened in 1892. Under the false name of “Craig’s Restaurant,” it became a popular speakeasy during the ’30s, run indirectly by the Democratic Party. Perhaps because of this, it’s received visits from multiple writers, including poet Seamus Heaney and Frank McCourt, who called it, “a place to talk.”

Take a seat at the bar, and you can witness the historical legacy for yourself. The bar has never gotten rid of its original dumbwaiters, and for the record, its urinals are also originals. The beautiful mahogany finish on the bar has also lasted through the years. While you enjoy a cold pint, check out the old fashioned cash register that still remains and watch the waiters operate the dumbwaiter the same as they did a century ago.

Bonus. Yonah Schimmel’s Knish Bakery (1910)

The renowned knishes of Yonah Schimmel‘s date back to before the store itself opened in 1910. 20 years earlier, Yonah, recently immigrated from Romania, began to make the rounds of the Lower East Side selling his handmade knishes from a pushcart. Although the shop’s leadership changed shortly after it moved into the established location on Houston, the Schimmel name stuck.

The bakery has since become a lasting icon of the Lower East Side. It was immortalized in a painting by Hedy Pagremanski that now hangs in the Museum of the City of New York, and was featured in Woody Allen’s film Whatever Works.

The Lower East Side has changed, but Yonah Schimmel’s bakery remains a beloved relic of a past era. The majority of the shop itself hasn’t been renovated since its first opening, and the owners claim the knish recipe has not been altered since the pushcart days. The menu features the same classics of Jewish cuisine — latkes, potato kugel, bagels, and borscht — that first won the heart of New York. The same philosophy applies to the sign above the door, which reads “Shimmel”, an original mistake that was never corrected.

Next, read about the 10 oldest bars and restaurants in Brooklyn!