New York is a city defined by its neighborhoods, and in Manhattan, there is one district that stands out for its heritage of unique architecture. In downtown Manhattan lies the SoHo district, whose name is an amalgam describing the area “SOuth of HOuston.” The moniker was first coined by city Planner Chester Raskin in a 1963 city planning report.

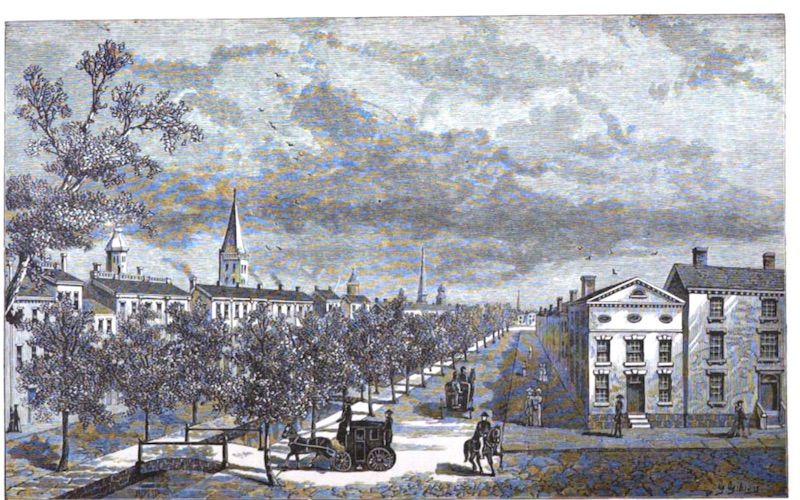

The neighborhood has had many incarnations since its early beginnings in the 17th century as New York’s first free Black settlement, granted to former slaves by the Dutch West India company. By the 1660s, the land was acquired by Nicholas Bayard, the nephew of Peter Stuyvesant, Director General of Dutch New York. The area maintained its rural character until the mid-18th century, but as the city’s population grew and development inched northward, the local marshes and streams were drained and hills 2343 leveled for development. Once Broadway was paved, it ushered in the construction of Federal and Greek Revival-style row houses and developed into a middle-class enclave.

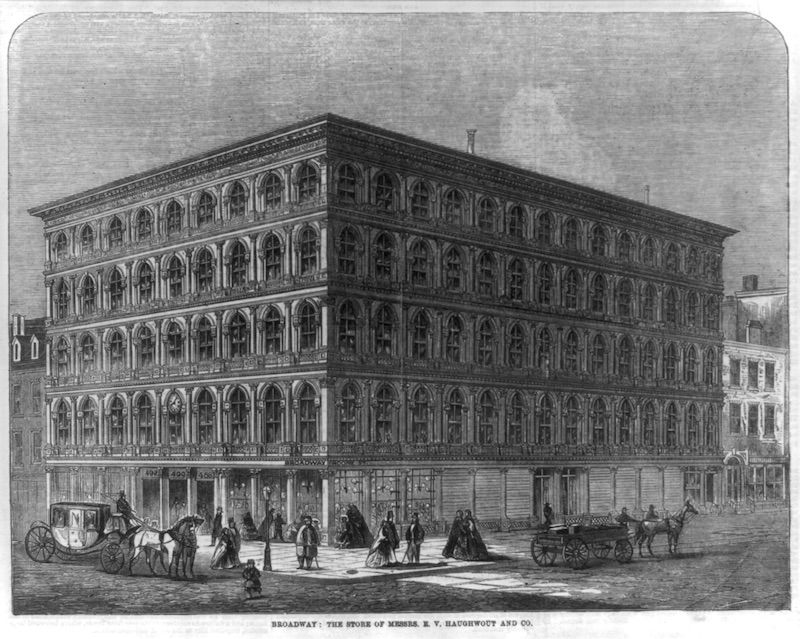

By the mid-19th century, the area became the heart of Manhattan’s burgeoning shopping, hotel, and entertainment district. This growth led to the development of more substantial buildings. Retail establishments such as Tiffany & Co. and Lord & Taylor got their starts in SoHo. Theaters, music halls, and bars sprang up along Broadway, with less respectable establishments located along the side streets. Brothels, primarily located on Greene and Mercer Streets, formed the city’s first red-light district. With the decline of the neighborhood’s residential character, many middle-class residents chose to relocate uptown. By the end of the Civil War, factories, mills, and warehouses started moving into the area, driving the need for larger industrial structures to accommodate machinery and storage needs.

For many years, cast iron had been used in bridge construction, building beams and columns, and decorative elements. Developed in New York, the timely innovation was to use cast iron not only for the structure but also for the façade. The primary advantage of cast iron was its ability to span longer distances than masonry, thus allowing for larger window openings to bring in more natural light. It also afforded more open floor space, important for arranging equipment and unfettered storage space.

The earliest example of a complete cast-iron building façade erected in New York City was introduced by James Bogardus, recognized as a pioneer of cast-iron architecture. The Edgar Laing Stores (1849) in the Washington Market District was the first self-supporting, multi-story structure with iron walls and served as the prototype for all cast-iron buildings that followed. It was designated a landmark in 1970 by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. When urban renewal all but cleared the district, the building was carefully dismantled and stored for subsequent reconstruction; however, the pieces were stolen — presumably to be sold for scrap metal.

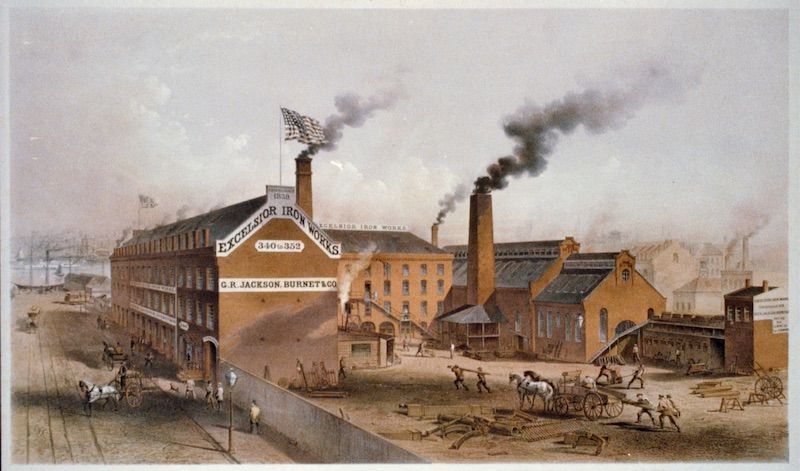

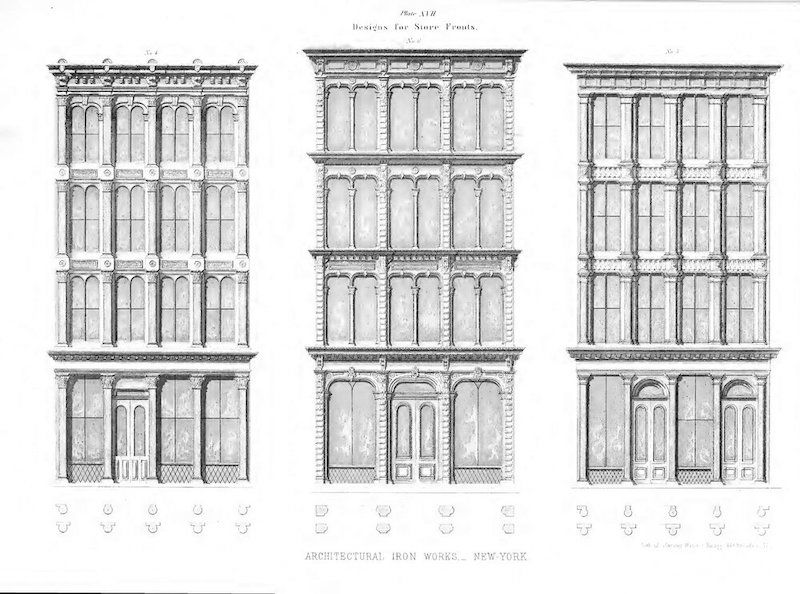

Casting building façades was cheaper than the typical masonry construction of the day. The castings were fabricated in local foundries, usually located near the East or Hudson Rivers where shipments of coal and iron could be received. Some were located only a few blocks from SoHo, which sped up delivery and construction. Many foundries offered stock building designs that could be selected from catalogs, streamlining the design process. The process of making cast iron started with wood patterns, which were pressed into sand molds to form a negative of the casting. Molten iron would then be poured into the mold filling all the voids. When cooled, the sand mold was broken, and the casting emerged to be finished by removing any overcasting and smoothing and priming it before shipping it to a site.

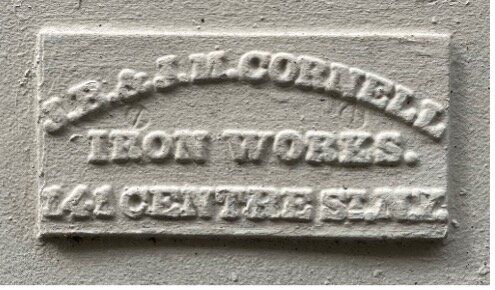

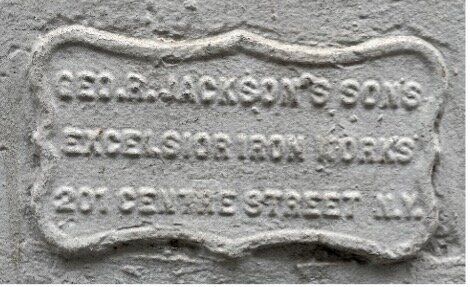

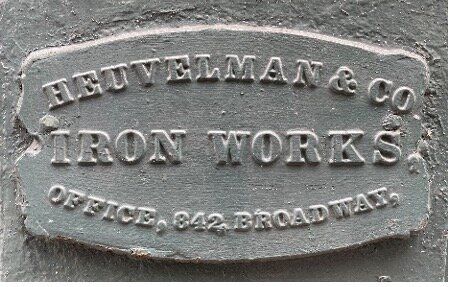

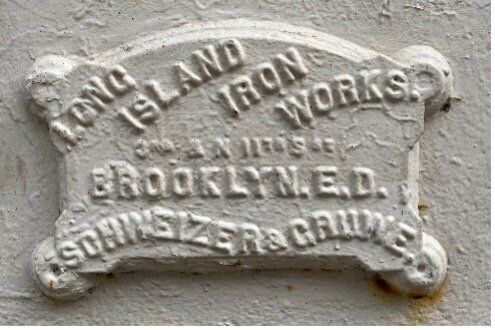

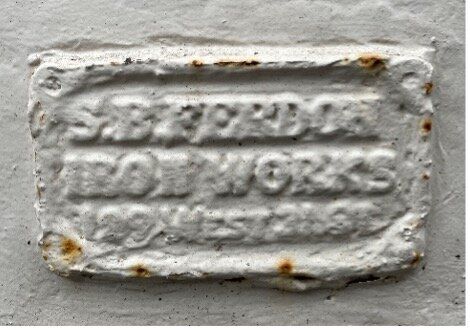

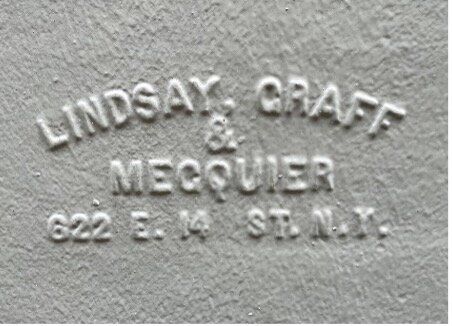

Some of the local cast iron foundries included Aetna Iron Works, James L. Jackson Iron Works., Badger’s Architectural Iron Works, Long Island Iron Works, S.E. Ferdon Iron Works, and Cornell Iron Works (still in business), to name but a few.

Foundry Plaques

Photos by Marc Gordon, courtesy of Spacesmith

While many clients opted to choose designs right out of a catalog, many prolific architects of the time (Henry Fernbach, Ernest Flagg, Griffith Thomas, John B. Snook, John Kellum, and Richard Morris Hunt) designed cast-iron buildings for their clients.

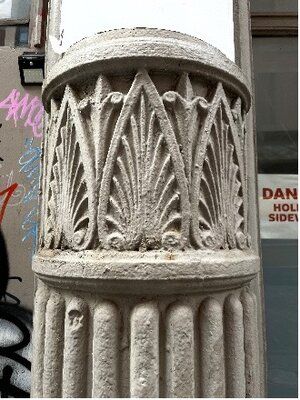

Castings could be customized with elaborate designs, and elements could be replicated uniformly as many times as needed. Cast iron could be produced much faster than cutting and carving stone, and it imitated the look of masonry façades once painted. New castings could easily be fabricated from existing patterns to replace damaged pieces. If needed, a façade could be disassembled and reassembled at a different location. Elements were lighter than their masonry counterparts, which made them easier to ship and handle. Cast iron façades were designed with an eclectic mix of primarily neo-Grec, Italianate, Renaissance Revival, and French Second Empire features, popular styles at the time.

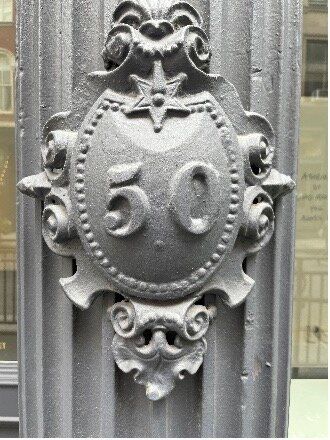

Cast Iron Address Plaques

Photos by Marc Gordon, courtesy of Spacesmith

Cast Iron Capitals

Photos by Marc Gordon, courtesy of Spacesmith

Cast-iron buildings were the forerunner of the skyscraper, presaging innovations such as curtain wall construction, standardized prefabricated building elements, and repeating bays. Another innovation that was introduced in a cast-iron building was the world’s first public passenger elevator, installed by Elisha Otis at the E.W Haughwout Department Store in SoHo.

Despite all this, the era of cast-iron architecture was relatively short-lived. Although the buildings were touted as incombustible, floor joists and girders, usually wood and unprotected, were susceptible to fire. With the decline of urban manufacturing after World War II, many industrial businesses started moving out and the neighborhood deteriorated into an industrial slum. After a devastating fire on Wooster Street in 1958 that claimed the lives of six firefighters, the FDNY commissioner, Edward Cavanagh, called the neighborhood “Hells Hundred Acres.”

By the ’60s, the fate of the neighborhood was in jeopardy. Robert Moses proposed ramming a federally funded highway project, the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMAX) through the heart of SoHo.

Luckily there was vocal opposition from a coalition of community groups headed by the activists Jane Jacobs and Margot Gayle. The project was ultimately defeated in 1969. Due to the efforts of preservation groups like the Friends of Cast Iron Architecture (founded by Margo Gayle), a large portion of SoHo was designated as a historic district by the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1973 and as a national historic landmark in 1978. While there are cast-iron buildings scattered throughout lower Manhattan, SoHo has the largest collection of full and partial cast-iron buildings in the world, with about 250 existing examples.

Cast Iron Details

Photos by Marc Gordon, courtesy of Spacesmith

Pioneering artists in the 1960s seeking studio space realized the open floor plates, high ceilings, and large windows of these buildings were ideal as live-work studios and started occupying the abandoned industrial lofts even though they were zoned for commercial and manufacturing uses. Since occupancy was technically illegal, the artist community banded together to form the Artists Tenants Association to petition the city to allow live-work occupancy in non-residential zoned areas. The city agreed as long as tenants could prove they were an “artist in residence.” Galleries soon followed the artists and SoHo was transformed into the city’s premier art district. Since it’s heyday in the 1990s and 2000s, many of the district’s galleries have been displaced by high-end boutiques and restaurants. In addition, the onset of gentrification has turned artist’s studios into million-dollar residential lofts.

While the next chapter in the life of SoHo is yet to be written, the heritage of New York’s cast-iron district will remain a unique example of a stylistic and technological moment in time for fans of architectural design to appreciate and enjoy for generations to come.

Marc Gordon, AIA, LEED®AP BD+C Partner, is a practicing architect in New York, where he’s a partner at the firm Spacesmith. This is his third article for Untapped Cities, following up on Trinity Church’s Four Cemeteries in NYC and 8 Disappearing Neighborhoods and Districts.

Next, read about the top 10 secrets of SoHo!