After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

The Upper West Side, a neighborhood extending from West 59th Street to West 110th Street between Central Park and the Hudson River, is a primarily residential and wealthy area with lots of historic sites and cultural institutions. The home of Lincoln Center and the American Museum of Natural History, the Upper West Side is a popular tourist destination, drawing many to sites like Riverside Park or the New-York Historical Society. Many may picture the Upper West Side as having tall historic apartments for the city’s elite, but there are plenty of spots that are under-the-radar or rarely visited along the famed Riverside Drive or West End Drive to discover. Here’s our guide to the top 10 secrets of the Upper West Side.

From the late 1800s into the early 1900s, the Upper West Side experienced an apartment boom, thanks to major investments from real estate developers. Dozens of high-rises began popping up along and near the Western edge of Central Park, Among the earliest apartments built in the area that still stand today are the Belnord, constructed in 1908 and housing figures such as Isaac Bashevis Singer, and the Apthorp, built between 1906 and 1908 for William Waldorf Astor. Along “the Boulevard,” or the historic Bloomingdale Road, were many hotels, as well as vacant lots owned by developers waiting for the right time to start construction.

Many of these buildings were the creations of famed architect Emery Roth, the mastermind behind the San Remo, the El Dorado, and the Beresford on the Upper West Side. Roth contributed many designs in the 1920s and 1930s, a few decades after the initial apartment boom. The subway system, which opened in 1904, provided easier access to the Upper West Side, which became a popular destination for the city’s elite. With the construction of these buildings came the development of the area’s character; along West End Avenue were quiet residences, Columbus Avenue drew in many successful businesses, Amsterdam Avenue featured rather inexpensive apartments, and Riverside Drive was the center of elegance.

Pomander Walk on 95th Street is one of the Upper West Side’s hidden gems, carved out mid-block between Broadway and West End Avenue. The private street, accessible only to residents, was first designed in 1921, and it has retained its elusive and exclusive charm exactly 100 years later. Pomander Walk was the brainchild of Thomas Healy, an Irish immigrant and successful restauranteur and hotelier who was one of the first to be indicted under federal Prohibition laws. Landmarked in 1982, Pomander Walk was described as “a prototypically ‘American’ tale combining a pragmatic entrepreneurial spirit with an unabashed romanticism” by a Landmarks Preservation Commission report.

Pomander Walk was named after and inspired by a popular play set on a London street from the Georgian Period. Although Pomander Walk consists of mass-produced housing, many of the details are visually compelling, even if they’re non-functional. The Tudor details are of wood-wrapped steel on the facades, which made the original houses quite cheap ($2,950, or $42,701 today). Facades consist of three different types of stucco in contrast with brick, and roof styles also vary from one house to another. The flower boxes and most of the doors are original to the design.

Septuagesimo Uno Park, Latin for “seventy-first,” is one of the smallest parks in New York, measuring just 0.04 acres. Although there are smaller parks across the city, including various triangles throughout the five boroughs, this park features lots of greenery, a central walkway, some benches, and … not much else. The Commissioners Plan of 1811 did not take into account park acreage for recreation, so by the 1960s, land was becoming extremely scarce. Mayor John V. Lindsay began a campaign in support of “vest-pocket parks,” constructed on small vacant lots often between two buildings.

The park, which received a renovation in 2000, was first called “71st Street Plot,” but was renamed around the turn of the century. The park wasn’t officially opened by the Parks Department until May 1981. In an article from 2013, Untapped called the park “a forgotten dead-end alley that has been reclaimed by Mother Nature.” In addition to this park, check out other quaint secluded gardens, including the Lotus Garden, West 87th Street Garden, and the West Side Community Garden.

At 89th Street and Riverside Drive is the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument, a large tower that piques the curiosity of parkgoers. The memorial was built in honor of those who fought in the Civil War. It has an intricate mosaic interior that has for the most part remained hidden to the general public. It was dedicated on Memorial Day 1902, without its planned but never completed battlemented wall and grand staircase descending to a watergate. By the 1950s, the monument deteriorated to the point that a fence was erected to protect the public from falling masonry, but a decade later it was restored.

Yet the monument that many pass by daily on their walks through Riverside Park was originally supposed to be further south. Mayor William Lafayette Strong suggested putting the memorial at Grand Army Plaza at 59th Street and 5th Avenue. The original plan consisted of a 125-foot column capped by a statue of Victory, but that design was replaced by a new 80-foot high monument inspired by the Athenian Chorgaic Monument of Lysicrates. The Riverside Drive viaduct was also heavily considered as the site of the monument. The final location at 89th Street was finalized in 1899, and the memorial was dedicated in 1902.

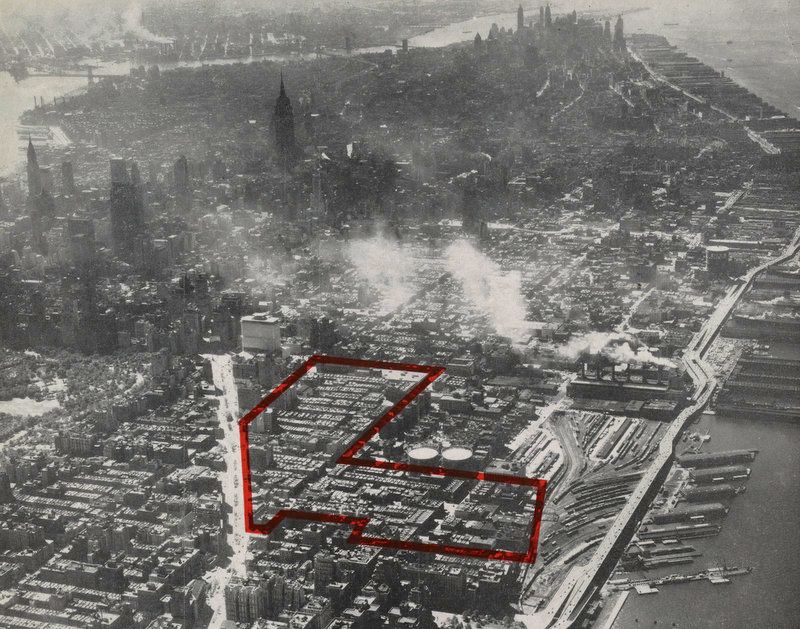

Perhaps American history buffs know the term “San Juan Hill” from the Spanish-American War battle in Cuba, but perhaps fewer know that the Upper West Side used to have its own San Juan Hill neighborhood. San Juan Hill was a community in what is today Lincoln Square that had one of the largest Black populations in the city prior to World War I. The neighborhood, mostly inhabited by African Americans and Puerto Ricans, was bounded to the south by 59th Street and to the north by 65th Street. The name of the area has unknown origins — some believe the name was inspired by the battle, since some African American veterans moved to the area, but others think it may have derived from conflicts between African American residents and local Irish American gangs.

Many of San Juan Hill’s first residents moved from Greenwich Village, and the area quickly developed its own arts and jazz scene before the construction of Lincoln Center. The area had many basement clubs inside tenements, as well as a popular club called Jungle Cafe. A few years before the turn of the century, many Black churches began opening in the neighborhood, which grew significantly following the Spanish-American War. Much of the area’s culture and history was erased, though, due to urban renewal projects that pushed many Black residents northwards to Harlem.

Sections of San Juan Hill were demolished in 1947, and thousands of families were evicted or displaced to make way for other apartments. Robert Moses claimed the land of the “slum” due to eminent domain, and by the 1950s the area was almost completely torn down. The demolition of sections of San Juan Hill was actually halted for the filming of West Side Story, which includes shots of actors standing amid piles of debris.

The Upper West Side is home to one of the country’s largest Jewish communities, which developed when German Jews moved here prior to the turn of the 20th century. Between 85th and 100th Street is today considered the country’s largest community of young Modern Orthodox singles, and many of the restaurants in the neighborhood are Glatt Kosher. The neighborhood also features many historic synagogues; the first “Free Synagogue” branch called Stephen Wise Free Synagogue, New York’s second-oldest synagogue B’nai Jeshurun, and Congregation Shearith Israel, the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States.

Congregation Shearith Israel, often called the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue, was established in 1654 in New Amsterdam by Jews who immigrated from Dutch Brazil. It was the only Jewish congregation in New York City until 1825, when German Jews started to arrive. The congregation, now on Central Park West and 70th Street, could not build a synagogue until 1730 on Mill Street, which was located near a spring for mikveh ritual baths. In 1886, Rabbi Henry Pereira Mendes of the congregation founded the American Jewish Theological Seminary, where he later became president. In 1897, the congregation moved into its current Neoclassical building, and members have included poet Emma Lazarus and Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo.

The Claremont Riding Academy, located at 175 West 89th Street, was the last public stable in Manhattan and the longest-running equestrian stable in New York City. Built in 1892, the stable was designed by Frank A. Rooke, who designed numerous plants for Sheffield Farms. The complex hosted floors of stables and storage space for carriages, which were the primary method of transportation around that time. Rooke also designed stables at 167, 169, and 171 West 89th Street, which he sold to local families.

The Romanesque Revival building was the site of a riding school starting in 1927, and the building was at risk of demolition in 1961. The school struggled to stay open, though, as the Central Park bridle paths continued to deteriorate. The school shut down, along with the stables, and it was later purchased by the Stephen Gaynor School.

The Nicholas Roerich Museum, nestled right next to Riverside Park on West 107th Street, is a museum dedicated to prolific Russian artist Nicholas Roerich. Much of Roerich’s artwork focused on nature scenes from the Himalayas, but in his free time, he was also an archeologist, costume and set designer, writer, philosopher, and public figure. Housed in a three-story townhouse are over 200 works of art ranging from paintings of the Himalayas to sketches from his early days designing sets for Russian ballets, including The Rite of Spring.

The museum was originally located in the Master Apartments at 103rd Street and Riverside Drive, built for Roerich in 1929. Roerich received three nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize for his dedication to preserving wartime art, artifacts, and architecture. His activism led to the Roerich Pact, an inter-American treaty that gave legal recognition to the defense of cultural objects over military defense.

While many are familiar with the Gilded Age mansions of Fifth Avenue, which were found for the most part in Midtown, a few mansions extended up to the Upper West Side. Perhaps the most famous was the Charles M. Schwab House, a 75-room mansion between 73rd and 74th Streets. It was constructed for Schwab, who grew Bethlehem Steel to the second-largest steelmaker in the United States. The mansion was considered one of the most prominent “white elephants,” or exquisite homes built on the “wrong” side of Central Park away from the elegance of the Upper East Side. The Beaux-Arts home included a mix of pink granite features and took inspiration from three French Renaissance châteaux. Quite hilariously, Schwab’s former boss Andrew Carnegie, whose mansion became the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, quipped that Schwab’s home made his look like a “shack.”

Also on the Upper West Side was the Apthorp mansion, named after Charles Ward Apthorp, a member of the Governor’s Council during the American Revolution. Built just west of 91st Street and Columbus Avenue, the 168-acre home overlooked the Hudson River and was taken over by both American and British soldiers. Apthorp died in 1797, and the home was contested for decades between his children. Eventually, it became a dance and beer saloon, and it was also one of the sites of the Orange Riots of 1870. Other notable mansions include the Dr. Valentine Mott Mansion, named for a celebrated surgeon, on 93rd Street.

The Joan of Arc Memorial in Riverside Park was the first statue in New York of a non-fictional woman, as well as the first public sculpture created by a woman. The bronze equestrian sculpture on 93rd Street was designed by Anna Vaughn Hyatt Huntington, who received the Chevalier of the Legion of Honor by the French government for her work. The statue was commissioned to commemorate the 500th anniversary of Joan of Arc’s birth, and it was dedicated on December 6, 1915, in a ceremony presided over by the French Ambassador and Mrs. Thomas Alva Edison. Huntington emphasized “the spiritual rather than the warlike point of view” in creating the memorial.

For Joan’s armor, Huntington did research at the arms and armory division of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her horse design was based off one borrowed from the fire department of her native town of Gloucester, Massachusetts. And to depict Joan on horseback, her niece posed atop a barrel, first nude then in costume. The pedestal incorporates a World War One shell-shattered pilaster from Reims Cathedral, as well as sections of the walls of the prison where Joan of Arc was held in Rouen.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Riverside Park and the Top 10 Secrets of Morningside Heights!

Subscribe to our newsletter