New York City may be famous for its skyscrapers, but it’s the Beaux-Arts buildings erected during the Gilded Age that transformed the city into the exciting metropolis it is today. This period after the Civil War was characterized by unprecedented growth and modernization, with industrial tycoons amassing huge fortunes that they used not only for their own benefit but also to beautify the city — namely by constructing the kinds of Beaux-Arts buildings that existed in Europe. Architects like Richard Morris Hunt and Charles Follen McKim trained at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and used European architecture as inspiration for the grand museums, libraries, bank buildings, monuments, and residences commissioned by wealthy patrons like the Astors, the Vanderbilts, and the Carnegies.

“On returning from Paris, Hunt, McKim, and the others were tasked with forging a new architectural identity for the flourishing nation, and for its leading city. The street was their canvas, and the Beaux-Arts style their brush, as they transformed New York from a provincial city of mediocrity into an international metropolis of awe and wonder,” Phillip James Dodd writes in the introduction to An American Renaissance: Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York City. Published by Images Publishing, the new tome offers an in depth look at 20 of New York’s most incredible Beaux-Arts buildings and the stories behind them.

We’ve chosen ten gorgeous Beaux-Arts buildings in New York City that every architecture fan should see at least once in their life. To learn more about the book and Beaux-Arts architecture in New York, join us for a virtual book talk with Phillip James Dodd on January 12, 2022 at 12 p.m. This event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. If you’re not a member, join now (and use the code JOINUS to get your first month free).

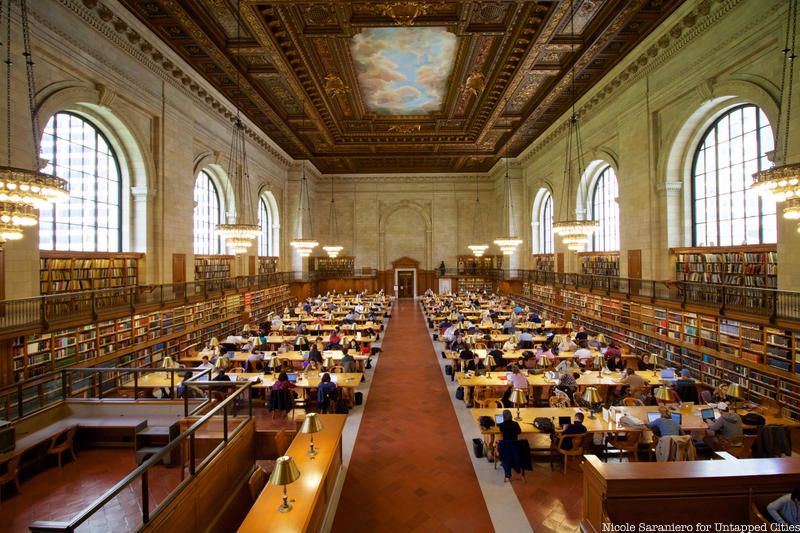

1. New York Public Library

Undoubtedly one of New York City’s most recognizable Beaux-Arts buildings, the New York Public Library’s main branch at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue was designed by Carrère & Hastings, a firm that was just beginning to gain acclaim when it won the design competition. Amazingly, the firm’s founders John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings beat out their old bosses at McKim, Mead & White for the commission.

Their insistence on using gleaming white Vermont marble blew the budget up from $2.5 million to $9 million and due to their exacting standards, the library took nine years to build. They drew inspiration from Roman triumphal arches, the Opéra de Paris, and Hôtel de la Marine on Place de la Concorde in Paris and borrowed elements like fret moldings and rosettes from ancient Greek architecture. As Dodds writes, “this building comes closer than any other in America to the complete realization of Beaux-Arts design at its best.”

2. Grand Central Terminal

Commissioned by Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, Grand Central Terminal was constructed just a few years after the original Penn Station. A competition won by Reed and Stem — a firm based in St. Paul, Minnesota that had gained a reputation for designing train stations around the U.S. — awarded them the commission, but William Kissam Vanderbilt (the Commodore’s grandson) brought in Warren and Whetmore to design it jointly. The arrangement was fraught and ended in scandal, but the station turned out to be a masterpiece nonetheless.

The construction of Grand Central took ten years, cost more than $2 billion in today’s dollars, and employed 10,000 workers. It opened in 1913 and to this day remains the largest train station in the world. The main concourse alone measures 275 feet long by 120 feet wide and is the equivalent of 12 stories tall. Its barrel vaulted ceiling is painted turquoise and adorned by a celestial ceiling mural. Parisian artists sculpted decorative elements, including the oak leaves and acorn that the Vanderbilts adopted as their family emblem. But the crowning achievement is the Tiffany clock (the world’s largest) and sculpture of Mercury flanked by Minerva and Hercules on the façade, which measures 48 feet high and weighs 1,500 tons.

3. The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the late 1800s, New York City reached unheard of levels of power and prestige, but the city lacked a museum worthy of such an important global financial center. The Metropolitan Museum of Art was conceived to fill this void and was meant to rival the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The museum was incorporated in 1870 and quickly outgrew its original location in a Fifth Avenue brownstone. The city agreed to fund the museum’s construction, deeded it 18.5 acres in Central Park along Fifth Avenue, and chose Calvert Vaux as the architect. However, it was the subsequent expansion by Richard Morris Hunt that transformed the Met into the architectural landmark it is today.

Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, Hunt was a trailblazing architect who earned the nickname “the dean of American architecture.” His design for the Met drew inspiration from Greek and Roman classicism, specifically the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. He hired the Guastavino Company to construct the domes in the Italian Renaissance style and commissioned Karl Bitter to create 31 pieces of sculpture for the façade, which were never finished due to budget cuts. Still, the building is a masterpiece of Neoclassical architecture and a symbol of New York City.

4. The Frick Collection

When Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick moved to New York City in 1905, he initially rented one of the Triple Palaces built by Henry Vanderbilt, but when his partner-turned-rival Andrew Carnegie built a fabulous mansion on Fifth Avenue (now the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum), Frick was determined to one up him. He hunted for the most prominent location on Millionaires Row and hired Thomas Carrère of Carrère and Hastings to build him a grand mansion inspired by Parisian hôtel particuliers, which he would fill with his art collection — one of the finest in the world.

Carrère drew inspiration from the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris and created a dramatic layout of rooms with enfilades leading to the garden, the courtyard, or a particular work of art. Frick then hired British decorator Sir Charles Carrick Allom to design the interiors, which feature paneled walls, cornices, and grand fireplaces. He created a whole room dedicated to Fragonard, filled with 14 panels that the artist had painted for Madame du Barry, Louis XV’s mistress. Frick bequeathed the mansion and his incredible collection to the city upon his death and to this day it’s one of New York’s finest art museums as well as one of the city’s most impressive Beaux-Arts buildings.

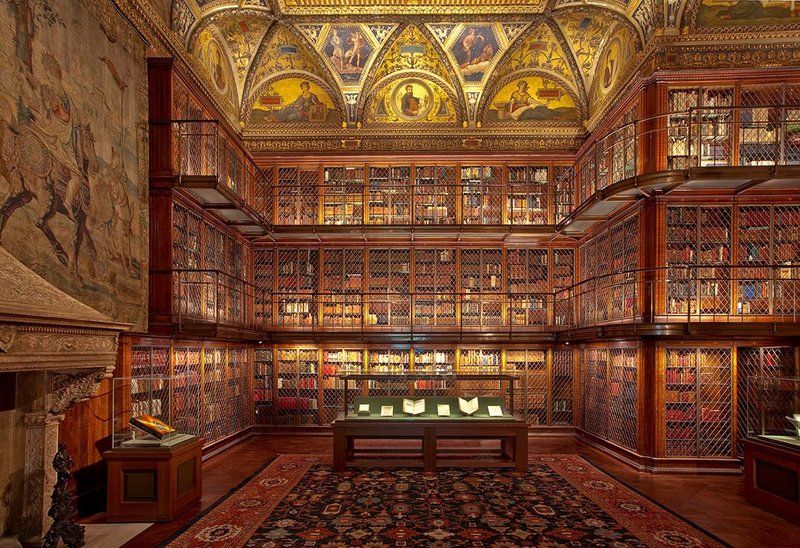

5. The J.P. Morgan Library & Museum

A contemporary of Frick, John Pierpont Morgan was the Gilded Age’s most powerful financier, which earned him the nickname “the Napoleon of Wall Street.” Unlike many of his contemporaries, he wasn’t interested in living on Millionaires Row or flaunting his wealth. He preferred to use his considerable fortune for philanthropic endeavors and to amass an incredible collection of European art and books, with the goal of turning New York City not just into the financial capital but also the cultural capital of the United States.

By 1900, his Murray Hill residence had become overcrowded with his art, so he purchased the two adjacent properties and convinced Charles McKim to design his new home by agreeing to finance McKim’s passion project, the American Academy in Rome, for life. A master architect with myriad influences, McKim designed an Italianate home and library, taking inspiration from a number of Renaissance palazzos, including Villa Giulia and Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome as well as the Palazzo del Te in Mantua. The interiors are richly decorated with marble, lapus lazuli columns, mosaics, damask wall coverings, and lavishly painted ceiling frescoes. After his death, Morgan’s son Jack fulfilled the wish left in his will that his library be turned into a museum.

6. National Arts Club

The stately Greek Revival townhouse that now houses the National Arts Club was once home to Samuel Tilden, who was elected governor of New York in 1875 after taking down the infamous William “Boss” Tweed. After winning 51% of the popular vote but losing the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes, Tilden retreated to his home and focused on renovating it. He hired Calvert Vaux to combine two adjacent townhouses into one palatial mansion overlooking the prestigious Gramercy Park, which was inspired by the residential squares and private parks of London.

Vaux set about combining the two homes, modernizing the façades, creating lavishly decorated interiors, and adding an escape tunnel for Tilden, who feared retaliation from Tweed’s associates. He decorated the façade with elaborate carvings of leaves and a decorative panel sculpted with busts of Tilden’s favorite authors, including Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe, and Dante. The interiors feature dark walnut boiserie and carved wood fireplaces, but the crowning achievement is the cove domed ceiling by Donald McDonald made with small pieces of yellow, gold, and white glass and inspired by Islamic geometric designs.

7. Williamsburgh Savings Bank

One of only two surviving buildings by George B. Post, the Williamsburgh Savings Bank is one of the earliest and finest examples of Beaux-Arts architecture in New York City. It was built in 1875, shortly after the erection of the Williamsburg Bridge turned the neighborhood into a thriving industrial center. Unlike other banks at the time, the Williamsburgh Savings Bank allowed its customers to deposit small sums of money, a policy that contributed to its enormous growth and success.

When the bank’s trustees decided to construct a new building, they turned to Post, an apprentice of Richard Morris Hunt and one of the leading architects of the time. He designed it in a combination of ancient Roman and Italian Renaissance styles, with a monumental dome modeled on Brunelleschi’s Duomo in Florence. Peter Bonnet Wight designed the interiors in the High Victorian Gothic style, with the dome painted a celestial blue with geometric motifs and offices decorated with mahogany paneling, Victorian wallpaper, and mosaic floors. After years of neglect, the building was restored to its former glory and now houses an event space called Weylin B. Seymour.

8. The University Club

One of the hallmarks of the Gilded Age was the advent of private members clubs inspired by the ones in London and accessible only to the upper echelons of society. In New York City, a number of these clubs began springing up, including the Metropolitan Club, the Players Club, the New York Yacht Club, and the Harvard Club. Established in 1865, the University Club declared its mission as “the promotion of literature and art, by establishing and maintaining a library, reading room, and gallery of art, and by such other means as shall be expedient and proper for such purpose.”

It was housed in three different locations before acquiring a large lot on Fifth Avenue between 54th and 55th Streets when St. Luke’s Hospital moved to Morningside Heights. Unsurprisingly, McKim, Mead & White — whose founding partners were all members — were hired to design the grandiose new building, one of the New York’s most glorious Beaux-Arts buildings. They combined elements from several Italian Renaissance palazzos, including Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and Palazzo Bocchi in Bologna. By forgoing a grand central staircase, they were able to create monumental rooms, each one more incredible than the next. There’s the grand salon, the stunning library, the dining room, the tap room, billiards room, and guest rooms as well as a gym, swimming pool, and Turkish Baths in the basement.

9. General Grant National Memorial

General Ulysses S. Grant emerged as the hero of the Civil War and the president who restored peace to a fractured country. Though it’s hard to imagine a presidential monument being erected on a similar scale now, in the years following the Civil War, Grant enjoyed a popularity on par with Lincoln and Washington. In fact, his tomb was privately funded, with almost 100,000 Americans donating the equivalent of $18 million in today’s dollars.

Following two separate competitions, John H. Duncan was awarded the commission to design the tomb. He devised an elaborate plan based on Napoleon’s tomb at Hôtel des Invalides in Paris with elements from the tombs of the Roman Emperor Hadrian and King Mausolus at Halicarnassus thrown in. Due to budget constraints, most of the sculptural elements he envisioned were cut from the plans, but the result was nonetheless one of the city’s most beautiful Beaux-Arts buildings. Grant’s tomb sits below a massive dome with allegorical figures poised in the spaces between the arches. Additional decorative elements were added by John Russell Pope in 1929.

10. The Woolworth Building

Dubbed the “Cathedral of Commerce” the Woolworth Building in the Financial District was the world’s tallest skyscraper when it was built in 1913. Commissioned by Frank W. Woolworth, who revolutionized the way Americans shop with his five and dime stores, the tower epitomizes the optimism of the era. A number of technological innovations made a skyscraper of this scale possible, from the fabrication of lightweight steel to electricity and recently patented Otis elevators.

Woolworth hired Cass Gilbert and specifically instructed him to build a skyscraper taller than the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower (then the world’s tallest building), snubbing the company that denied him a loan. Gilbert looked to his recent travels in France and England for inspiration in designing a Gothic Revival tower, specifically referencing the abbeys of Mont St. Michel and St. Ouen in Normandy and the Victoria Tower in London. He incorporated gargoyles, mythical beasts, flora, fauna, and coats of arms in the decorative scheme. Inside, the sumptuous lobby is decorated with Byzantine-style mosaics, Greek marble, and gold-plated elevator doors created by Tiffany Studios. Though the building’s lobby has been off-limits since 9/11, people are sometimes let in for tours.

Next, read about 20 buildings in NYC designed by architect Stanford White!