After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

Surrounded by luscious green spaces and breathtaking waterways, Inwood serves as a tranquil and secluded enclave away from the hustle and bustle of downtown Manhattan. Interestingly, while Inwood is the northernmost neighborhood on the island of Manhattan, it is not the northernmost neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan. This distinction belongs to Marble Hill, which was isolated from Inwood after the construction of the Harlem River Ship Canal, which altered the route of the Harlem River.

Originally, Inwood’s land was home to the indigenous Lenape, who according to legend, sold Manhattan to Peter Minuit, the Director-General of New Amsterdam, right within the modern Inwood Hill Park. Later, the neighborhood would serve as a central battlefield during the American Revolutionary War, containing an encampment of more than sixty huts occupied by German Hessian troops in the British army from 201st to 204th Streets.

Through the early 20th century, Inwood remained mostly undeveloped, being home to some of the city’s last remaining farmland. Over time, the neighborhood slowly began urbanizing, though its rolling hills and lack of skyscrapers continue to give it a more relaxed atmosphere perfect for leisurely exploration. For much of the 20th century, Inwood’s population remained predominantly Irish and Jewish, but shifted to having a more predominantly Dominican population beginning in the 1980s — it currently has the highest concentration of residents of Dominican descent in New York City.

From the oldest remaining farmhouse in Manhattan to the borough’s first modular apartment building, there is much to discover in Inwood. Read on to learn more about the fascinating history and legacy of Inwood.

Accounting for almost half of the neighborhood’s land area is Inwood Hill Park, a 196-acre all-purpose recreational and cultural space that remains as Manhattan’s last natural forest and salt marsh. Apart from a few trails, Inwood Hill Park is mostly made of thick deciduous forest that has remained untouched since the colonial days. The park is home to over 250 different species of trees and flowers, some of which cannot be found anywhere else in the borough such as the “Dutchman’s breeches” (Dicentra cucullaria).

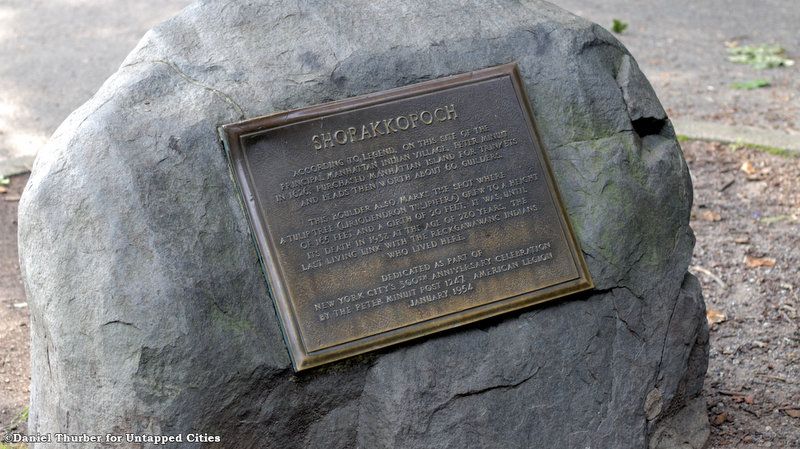

Located within the park are a number of Native American historic sites including the Shorakkopoch Rock, which marks the putative spot where Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan from the local Lenape people for the equivalent of $24 in 1626 — though historians continue to doubt the story’s veracity. Every year, the one-day Drums Along the Hudson festival takes place inside the park, celebrating Native American culture and the historical significance of the Shorakkopoch Rock.

A few minutes away from the rock are the “Indian Caves,” which were used as shelter by the Lenapes. Despite their name, these caves are actually recesses’ among large rock formations which date back to the times of the glaciers and were rediscovered during archeological investigations at the turn of the 20th century. Arrowheads have been found in the area by locals as late as the 1950s. Besides being used for shelter, the “Indian Caves” also served as a natural water spring and were useful for their proximity to the Spuyten Duyvil Creek for fishing. Over time the creek was altered to create the Harlem River Ship Canal, widening the connection between the Hudson and Harlem rivers, with other surrounding water areas being covered to create more parkland courtesy of Robert Moses, an American public official, and creator of the modern suburbs of Long Island.

Fort Cockhill, also known as Fort Cock or Fort Cox, was built by the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War as an 18th-century military fortification to serve as an outpost of Fort Tryon. Overlooking both the Hudson and Harlem Rivers on the northwestern extremity of Tubby Hook Hill (now known as Inwood Hill Park), the fort acted as a defense for northern Manhattan, being a five-sided, circular structure measuring ten to twelve feet in height. In addition, the fort was equipped with two cannons.

On the morning of November 16, 1776, during the Battle of Fort Washington, Fort Cockhill was attacked and captured by a troop of Hessian soldiers working for the British Army. Renamed Fort George after its capture, it remained under British control until the end of the war seven years later.

In a small park at the corner of Broadway and 204th Street is the Dyckman Farmhouse Museum, the oldest remaining farmhouse in Manhattan and one of the oldest buildings in Manhattan. Following the end of the British occupation of Manhattan during the American Revolution in 1783, the original Dyckman family homestead and orchards located near 210th Street and the East River were left in ruins. As a result, William Dyckman, the grandson of Jan Dyckman — who moved to the surrounding area from Westphalia, Germany in 1661 — began building a new Dutch-colonial farmhouse in 1784, this time located directly on Kingsbridge Road, now known as Broadway.

After William died in 1787, the house was inherited by his son Jacobus. By 1820 the Dyckman family holdings consisted of 250-280 acres of farmland stretching from river to river east to west and down from modern-day 213th Street to the 190s. Given the rocky terrain of northern Manhattan, the land could only be used to grow crops such as corn, cucumbers, cabbage, hay, cherries, and apples. Besides the farmhouse, the land also consisted of three additional homes, corn cribs, a barn, stable, and a cider mill,

In 1868, following the death of Jacobus’ last son Issac, money and select plots of the family’s land were accorded to Jacobus’ youngest grandson James Frederick Smith, so long as he changed his last name to Dyckman. The remainder of the Dyckman property, which by then amounted to 340 acres, was stipulated by Issac in his will to be sold, with the proceeds going to various family members. The land was sold at four separate auctions from 1868 to 1871, officially ending the Dyckman’s monopoly on the area, opening it up to further development.

Over the following years, the farmhouse fell into disrepair but was rebought by James’ daughters Mary Alice Dyckman Dean and Fannie Fredericka Dyckman Welch in the fall of 1915 to ensure its preservation. Under their care, the house was restored and opened to visitors as a museum displaying objects from friends and family reflecting on the Colonial Revival movement in July 1916. In addition, visitors to the museum today can also view an excavated Hessian Hut, which housed British and German Hessian soldiers during the Revolutionary War. In the early 1900s, the hut was unearthed by historian and amateur archeologist Reginald Pelham Bolton, who in 1916 found a chimney, walls, and flooring — reconstructing them to create a full hut within the park containing the Dyckman farmhouse.

Through the early years of the 20th century, Inwood remained one of Manhattan’s most rural sections, and was described by Robert Perkins during the retirement ceremony of Reverend George Shipman Payson — pastor of the Mount Washington Presbyterian Church — as “a veritable wilderness, isolated from the rest of the city.” The neighborhood’s development began to pick up particularly after the extension of the 1 train to 207th Street, which prompted the construction of new apartment buildings on the east side of Broadway.

One of the most striking structures that formed as part of the neighborhood’s early industrial development was the Dyckman Oval, a sports venue that hosted boxing, wrestling, football, soccer, amateur baseball, and ice skating competitions. With a capacity of 4,500 occupants, the Dyckman Oval was constructed in 1915 on a triangular block bounded by Nagle Avenue, 204th Street, 10th Avenue, and Academy Street. The park was best known as being a home for Negro league baseball, with games being played by the independent black team the Cuban Stars as early as 1917. Despite its initial success, the park’s stands were demolished during the off-season of 1937-1938, and the space was turned into public housing in the 1950s.

As Manhattan’s rural land grew more developed, the farms that had once defined the area began to close. By the 1930s, Inwood was home to Manhattan’s last family-owned farm — run by the Benedetto family, who moved to the area in 1924. The farm was located close to the intersection of Broadway and 214th Street, occupying an entire city block. Crops grown on the farm included corn, tomatoes, lettuce, and string beans, with pear and peach trees providing an assortment of fresh fruits. In addition, the farm was home to chickens, rabbits, a goat, and a horse used for plowing the land. After being sold in 1954, the farm’s land was developed, closing the book on both Inwood and Manhattan’s rural holdings.

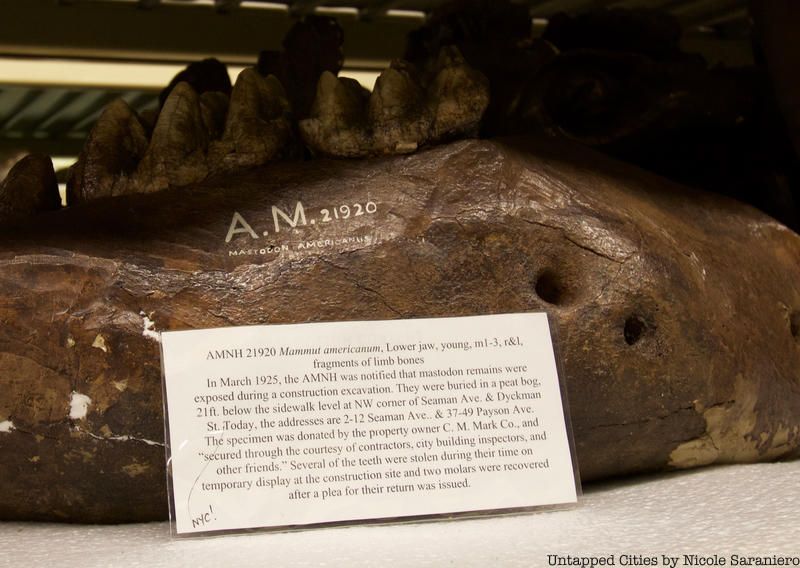

In 1925, at the intersection of Seamen Avenue and Cumming Street, a brand new apartment complex was set to be built when construction workers came upon the lower jaw and teeth of a young Mastodon (Mammut americanum) — an extinct species that lived in North America along the coast until around 10,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch. Immediately after the discovery, Dr. CC Mook from the American Museum of Natural History was dispatched to collect the fossils. However, before arriving, Inwood locals took off with the remains. As reported in The Sun on March 25, 1925, construction workers were showing off the fossils when a local milkman swiped them and ran away, leaving only three teeth left by the time Mook reached the scene. Later, two of these teeth were reported to have been pickpocketed from Mook as he made his way to his car from the construction site. Today, most of these stolen fossils have been recovered and returned to the Museum of Natural History

Besides the Inwood mastodon, other remnants of these prehistoric creatures have been found in various locations throughout the New York area. In 1705 a Dutch farmer unearthed the first mastodon fossil in Claverack, New York, a small town 100 miles north of Manhattan. After the farmer reportedly sold the mastodon tooth in exchange for a glass of rum, it eventually moved into the hands of the governor of New York and later the King of England. Moreover, given that the fossil was found around 100 years before the discovery of dinosaurs, many individuals believed that the tooth actually belonged to one of the giants in the biblical book of Genesis. In New York City, a piece of a tusk was also found during the digging of the Harlem River Canal.

One of the city’s most forgotten monumental arches is the Seaman-Drake Arch, a remnant of a hilltop estate built in 1855 by the once-wealthy Seaman family. In 1851 John Farris Seaman and his brother Valentine — who were the sons of Dr. Valentine Seaman, one of the men who brought Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccine to the United States — bought 25 acres of hilltop property stretching from what is now West 214th to 218th Streets. At the top of the property, the Seamans built a marble mansion in 1855, with the arch being built from the same material at the beginning of a road that wound up the hill to the house. According to the New York Times, the arch contained a low marble wall said to be an exact replica of the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

After the marriage of John Ferris Seaman to Ann Drake, the property and arch moved into both family’s possessions, becoming the headquarters of the Suburban Riding and Diving Club in 1895, of which Ann’s nephew Lawrence Drake was a part. A few years later in 1938, the Seaman-Drake estate was sold by its then-current owner Thomas Dwyer for the development of a five-building apartment complex, with the arch being left out of this sale. Since the 1960s, the Seaman-Drake arch has been part of an auto-body shop. Its structure was later severely damaged during a 1970 fire, leaving it roofless and exposed to the elements. Beginning in the early 2000s, efforts were made to provide legal protection to the arch by landmarking it. While this received support from New York City Councilman Robert Jackson, the arch remains un-landmarked and is not listed on the National Register of Historic Places. While the arch remains dilapidated and adorned with graffiti, the Seaman-Drake Arch stands as a paradox of urban history and a sight to behold.

Opened in 2003, Swindler’s Cove is one of upper Manhattan’s most beautiful parks, occupying around five acres of land along the Hudson River that was once used as a communal dumping ground. The park was created through a unique partnership between the New York Restoration Project, New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation, and the NY State Department of Transportation. Debris such as garbage, rusted cars, and sunken boats was excavated from the waterfront, making room for a series of ponds and waterfalls. In addition, the park consists of various birdhouses and a communal garden. Most interestingly of all, Swindler’s Cove has one of Manhattan’s only beaches.

Though much of Swindler’s Cove is bounded by hard, concrete edges, there is one sandy spot where visitors can relax and dip their feet into the water. The beach can be found by walking along the metal esplanade going over the park’s waterfront. Afterward, near the restored Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse is a small, unmarked dirt path that leads to a stunning view of the Manhattan shoreline. Though the signs of New York City are still quite visible from the beach, the spot also offers a glimpse into what the area might have once looked like before urbanization.

Ensconced between Inwood’s pre-war apartment houses is the Stack, Manhattan’s first modular apartment building. In a modular apartment, sections or modules of the construction are completed away from the building site and then delivered once the foundation has been prepared for assembly. As a result, construction speeds up by seven to nine months and costs drop by an average of 10-20%. In addition, the modules can be placed side-by-side, end-to-end, or stacked, allowing for a variety of new configurations or styles to be created. However, for all these benefits, prefabricated constructions disrupt long-standing construction practices in New York, posing a danger to the city’s construction unions by leading to the exportation of jobs to outside factories.

Debuting in 2014, the Stack was designed by architect Peter Gluck on a 50 foot wide lot previously designated as “Parking Facilities.” It is seven floors tall and composed of 56 modules. Sections of the Stack were manufactured in Berwick, Pennsylvania at the DeLuxe Building Systems. For Gluck, the Stack represents the evolution of architectural ideas stemming from the 1920s through the 1960s and will work in the future as an efficient tool to improve housing across New York City.

Along Inwood’s waterfront are a series of boathouses, with two being owned by Columbia University on the Harlem River Ship Canal near Inwood Hill Park at the northern end of the neighborhood. The first is the Gould-Remmer Boathouse, a white brick English-style clubhouse built-in 1931. The second is the Class of 1929 Boathouse, completed in 2001 in honor of the year in which the school’s rowing team last captured the national championship. This boathouse replaced the ‘97 Boathouse, which had been built by funds from the class of 1897 and opened in 1922.

In addition, Inwood is also home to the Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse, one of the Harlem River’s newest boating facilities. The boathouse opened in June 2004, becoming the first community boathouse of its kind on the river in over 100 years. Currently, it houses the non-profit organization, Row New York — providing young New Yorkers from under-resourced communities with rowing programs to instill pride, motivation, and life skills essential for college and beyond. In addition, the Peter Jay Sharp Boathouse is used by the rowing team of Fordham University and Manhattan College.

It was specifically created as an integral component of the New York Restoration Project, which sought to revitalize the surrounding Sherman Creek area. Once home to various boathouses during the 1950s, the area was left abandoned with illegal dumping by the 1990s. Today, Sherman Creek Park encompasses five reclaimed areas along the Hudson River, such as Swindler’s Cove, the Riley-Levin Children’s Garden, and the Harlem River Greenway — consisting of an esplanade, bike path, and cherry tree planting project on Harlem River Drive.

Founded in 1902, the Inwood Canoe Club (ICC) is the oldest remaining canoe and kayak club in New York City. The Inwood Canoe Club is located on the Hudson River in Fort Washington Park near Dyckman Street. By 1913, surrounding the club were five other boathouses. Eventually, these boathouses burned down, including the ICC’s twice. Despite this loss, while the other boathouses closed down, the Inwood Canoe Club was rebuilt and remained in operation. During the middle of the 20th century, the club primarily served as a training ground for canoe racers, with seven ICC members representing the United States in the Olympic Games between 1956 and 1984.

After losing its boathouse again to fire in 1988, the ICC rebuilt and rebranded itself as a recreational club for kayakers, canoeists, and SUPers. Over the years it has continued to grow and serves as an important community resource for teaching New Yorkers about paddling. On Sunday mornings in the summer, visitors can take complimentary 20-25 minute guided trips in a canoe or kayak north of the George Washington Bridge, with members having access to longer and more in-depth excursions.

Next, check out 20 Things To Do In Inwood, New York City!

Subscribe to our newsletter