Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

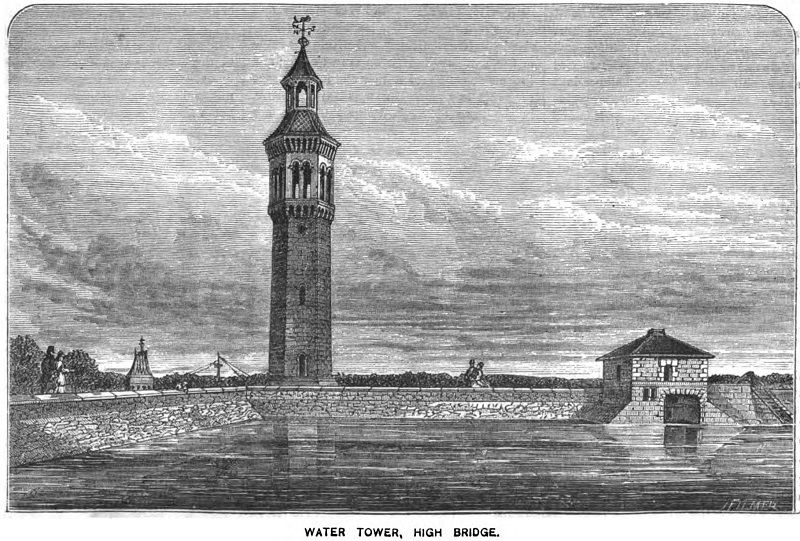

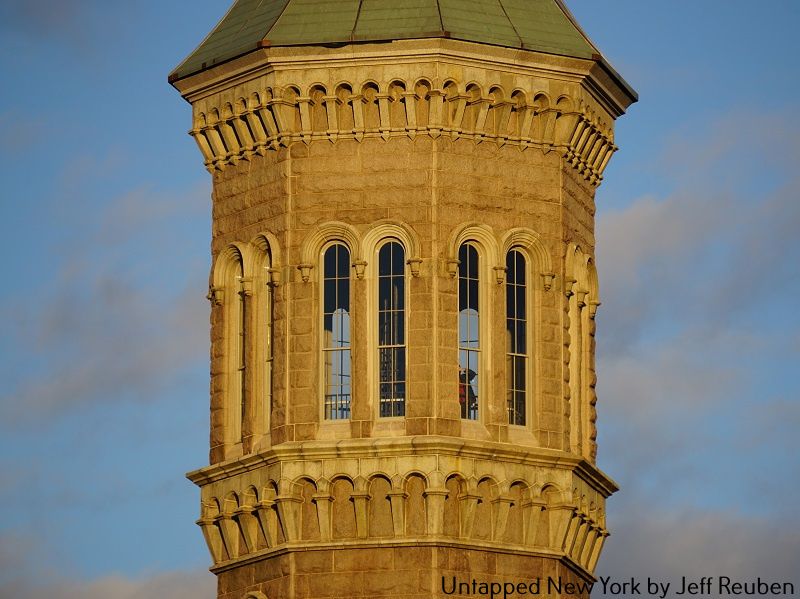

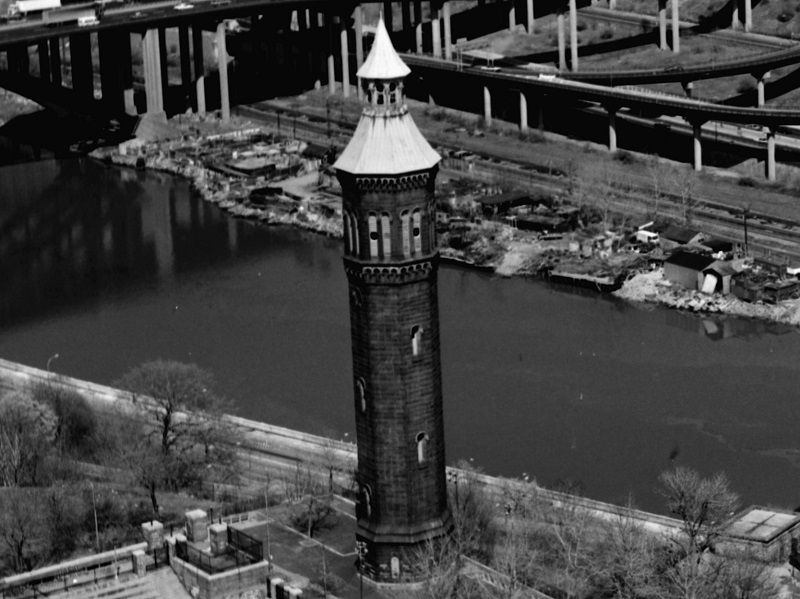

The 200-foot tall Highbridge Water Tower in Washington Heights stands on a bluff above the High Bridge and Harlem River, sharing a park landscape with a swimming pool, baseball field, playground, terrace, and lawns. It is a familiar, if somewhat mysterious landmark for local residents, MetroNorth Hudson Line commuters, and motorists on the Harlem River Drive and other nearby roadways and bridges.

However, when it was completed 150 years ago, its setting and function were quite different. Constructed as an addition to the Croton water system in a then thinly populated area, it was a major catalyst in the transformation of Upper Manhattan into bustling urban neighborhoods.

For many today, its origins and historic role are unknown, but it is time to rediscover this enigmatic icon, which is not only celebrating its sesquicentennial in 2022, but was also recently reopened for tours following a $5 million restoration. In celebration of its return to the spotlight, we present ten secrets of this distinctive structure.

Find out more about these and other facts and stories at our upcoming virtual talk about the Highbridge Water Tower on March 24th at 12 p.m. The event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. If you’re not a member, join now (new members get their first month free with code JOINUS).

When the Croton Aqueduct opened in 1842, providing Manhattan with an abundant source of clean drinking water, the system relied on gravity for water pressure. As a result, northern Manhattan was not served by the system given that much of it is at elevations higher than the reservoirs in Central Park and at 42nd Street. A bit ironic considering that the High Bridge, which carried the aqueduct over the Harlem River., became a defining feature of the area and a popular destination for visitors following its completion in 1848.

In an era when individual buildings did not have their own water pumps and tanks, a systemic solution was needed. So, the City’s Croton Aqueduct Department added the High Service Water Works to “cure the evil of limited supply to those whose ambition brought them above the level of the reservoir” as the New York Times elegantly phrased it in 1866. The site selected for these facilities was high ground near the Manhattan end of the High Bridge.

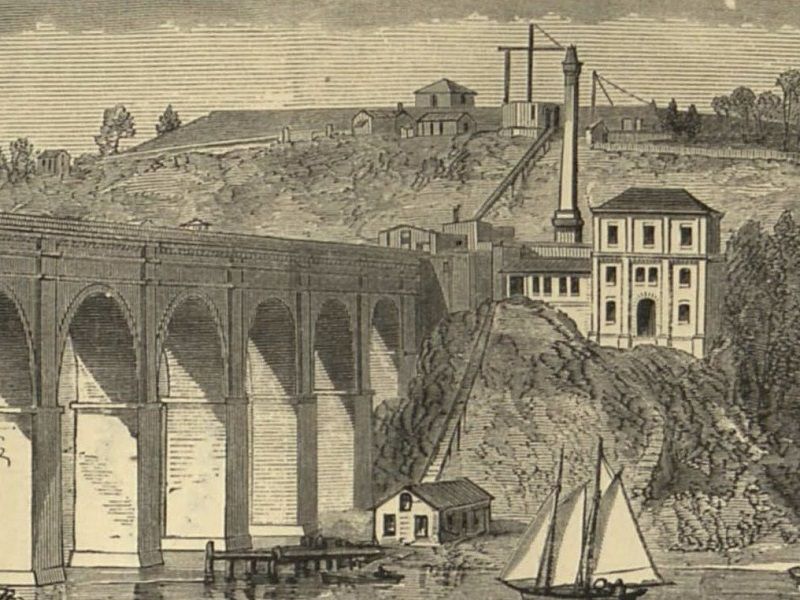

The Water Tower was just one part of this. As shown in the historic images above, next to it was a reservoir, opened in 1870, with a storage capacity of nearly 11 million gallons. It was high enough that it provided water pressure to serve 90 percent of the High Service Area; water pressure for the other 10 percent was provided by a 47,000-gallon water tank located inside the Tower.

Next to the High Bridge, there was also a pumping station with a steam engine, boiler, and smokestack to force water up from the aqueduct, a coal dock and shed along the waterfront, and an inclined plane to lift coal up the steep river bank to the pumping station. All except the Tower no longer exist, nor does another pumping station added in the mid 1890s about 1,000 feet to the north.

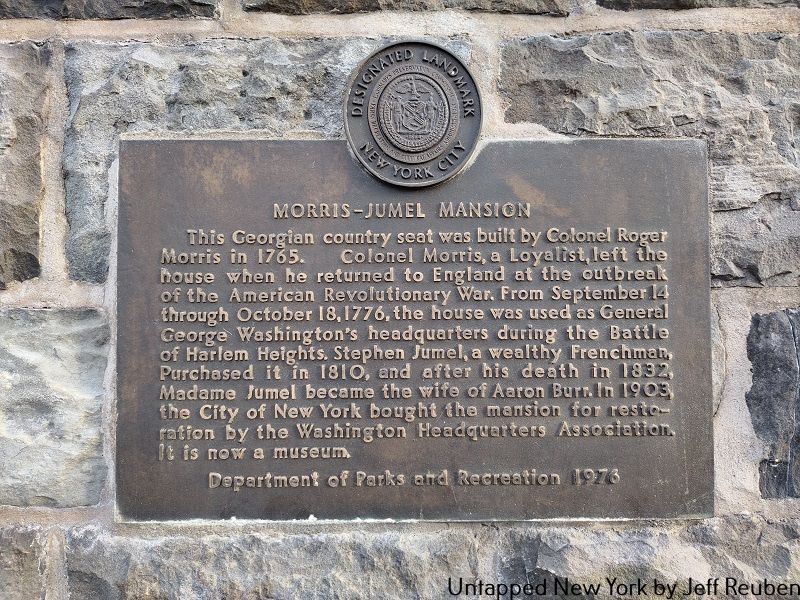

Describing the High Service Water Works plans, the New York Herald reported in 1864 that “this is to be done by means of a tower erected on Madame Jumel’s property, at High Bridge.”

This is a reference to Eliza B. Jumel, the American-born widow of French merchant Étienne (anglicized to Stephen) Jumel and ex-wife of Aaron Burr. Residing nearby in the Morris-Jumel Mansion, now a museum, she owned extensive real estate holdings including about seven acres where the City wanted to locate the High Service Water Works.

She offered this land for about $79,000, “to avoid the expenses which the City would necessarily have to incur to ascertain the value of the property.” The City rejected this and pursued an eminent domain taking, resulting in a Court approved compensation of $45,000. This substantial price reduction was a moot point for Madame Jumel; the process was completed in December 1865, six months after she passed away at age 90.

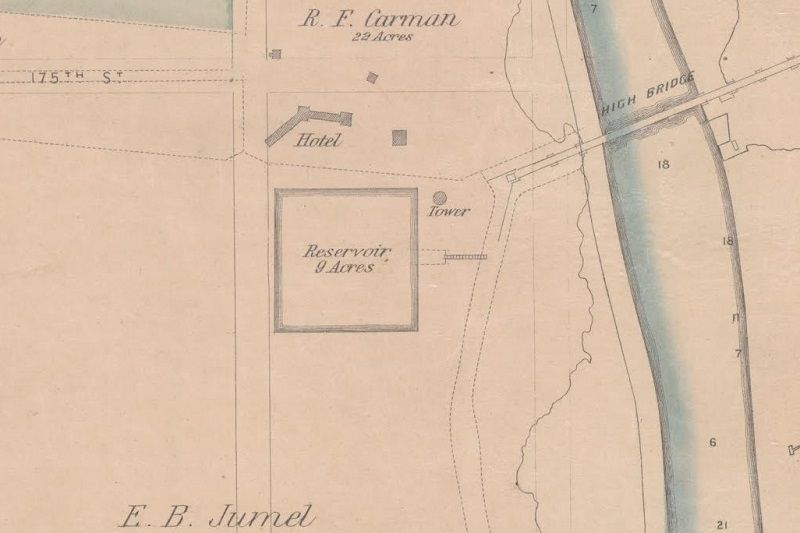

The map above from 1867 shows where the Water Tower and reservoir were to be placed and also indicates property boundaries (dashed lines) prior to the taking, including Jumel’s lands and the City’s aqueduct corridor extending south from the High Bridge.

Identifying who designed the Highbridge Water Tower is a matter worthy of attention, not least because many sources have credited it to the wrong person.

Contemporary accounts state that the High Service Water Works, including the Tower, were designed under the direction of Alfred W. Craven, who served as the Croton Aqueduct Chief Engineer from 1849 to 1868. Some sources also mention William L. Dearborn, who served as Engineer in Charge from 1862 to 1872. For what it is worth, Dearborn also signed plans for the Water Tower from the early 1870s.

“These extensive works have all been designed under the general direction of A.W. Craven, esq., engineer in chief of the Croton Department, by Wm. L. Dearborn, esq., Engineer in charge.”

New York Tribune, January 14, 1868. “Croton Department: New High-service Reservoir and Water Works at Washington Hights”

However, a century later in 1967 the City’s one-page Landmark Designation report states the Tower is “attributed to John B. Jervis.” One of the giants of American civil engineering history who was Croton Aqueduct Chief Engineer from 1836 to 1848, Jervis oversaw design and completion of the aqueduct and the High Bridge. However, after 1848 he went on to other endeavors and there is no evidence he designed the High Service Water Works. It appears that Jervis’ work on the High Bridge was conflated with the later Tower.

In an adult version of the children’s classic “telephone game,” many subsequent sources also state that Jervis designed the Tower, but dropping the “attributed to” qualification. It has become canon.

To correct the record, the designers should be identified as Craven, Dearborn, and their colleagues. Given the Water Tower’s distinctive architectural character, it is possible that some uncredited architect also played a role.

Although construction on the Water Tower did not begin until the summer of 1869, its design was completed by the spring of 1868.

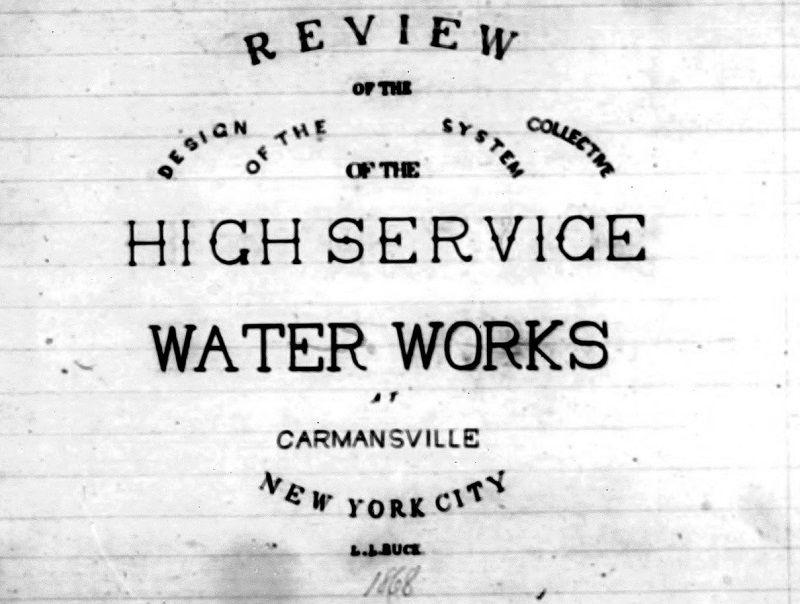

We know this thanks to a thesis written at that time by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute student L.L. Buck. It provides dimensions that are consistent with those in Dearborn’s early 1870s plans and its narrative descriptions and calculations are much more detailed than those in news articles or official reports. Who said schoolwork isn’t important?

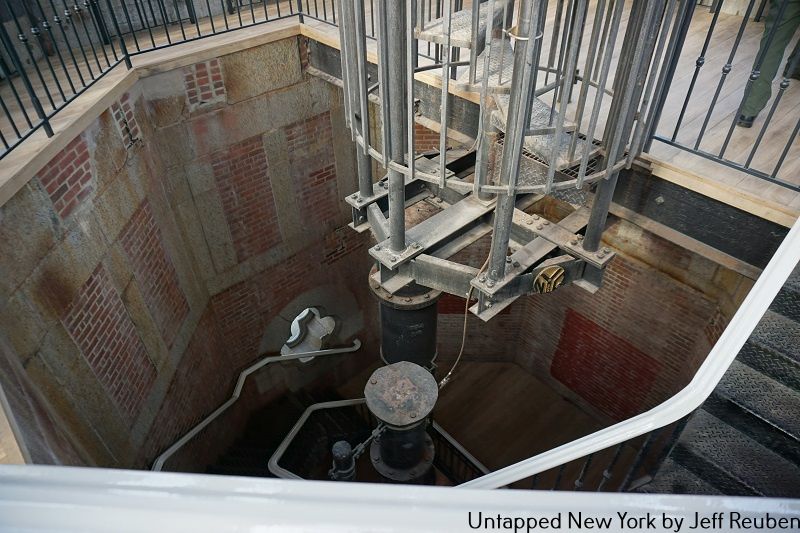

Among other things, the paper tells us that in the Tower’s interior there “will be a brick lining 8 inches thick and with an air space, between it and the stones of the wall, of 4 inches” and the stairs “are to be of iron, cast treads and wrought frame work in each story to wind from one side around to the opposite side, or occupying 8 sides, the landing on each floor to be vertically over that of the preceding.”

Incidentally, the student, whose full name was Leffert Lefferts Buck, went on to an accomplished career including serving as Chief Engineer on the Williamsburg Bridge.

Although built for a functional purpose, the Highbridge Water Tower is an ornamental building often likened to medieval minarets and campaniles (Italian bell towers) and the comparisons have considerable merit, both stylistically and structurally. The architectural connections are obvious, but the physical similarity is not as readily apparent until one ventures inside or looks at architectural drawings.

Built more than a decade before the first steel frame skyscrapers of the 1880s, the Water Tower has load bearing walls designed to support the weight of the building above, including a full water tank. Much like a historic church, it has thick walls at the bottom and thinner ones at upper levels.

Both Buck’s paper and Dearborn’s plans show that at the base the octagonal structure has an outer diameter of 29 feet and walls 5.5 feet thick, leaving only 18 feet inside. Above the base, the main shaft tapers slightly so that the walls are 4 feet thick but the interior space remains 18 feet across. The few windows in the base and shaft are narrow and vertical to maintain the structural integrity.

In contrast, the walls of the tank room, which is now the observation level, only support the weight of the cupola above. They are a much slimmer 1 feet, 4 inches thick and have expansive windows, two on each of the eight sides. As a result, this part of the tower has a more spacious, light-filled interior of 25 feet, 8 inches in diameter.

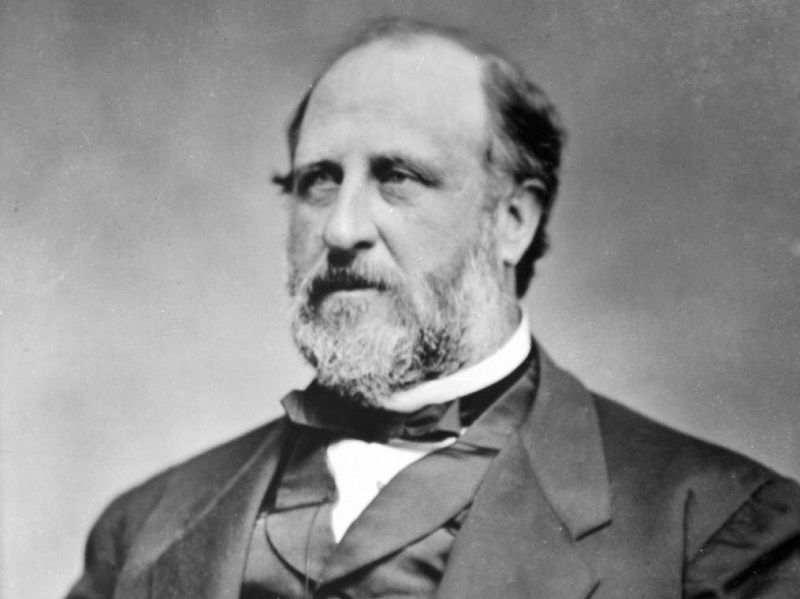

A silver-plated model of the Highbridge Water Tower, now owned by the New-York Historical Society, bears a lengthy inscription stating that it was presented to John L. Brown, the building contractor, “by the Employees on the Tower Works, as a Souvenir of the pleasant times passed in his employ.” It also lists various City officials, among them William M. Tweed, Commissioner of Public Works. In fact the linkage between the two was more than incidental.

Brown, who the New York Times once referred to as “the Tammany street-cleaner and contractor,” told an investigatory commission in 1872 “I had no connection with Mr. Tweed.” However, “Boss” Tweed acknowledged in 1877 what many long suspected; he held a secret interest in Brown’s street cleaning company and ensured that it received city contracts and payment for work it did not perform. In jail by then, he made confessions like this in an unsuccessful effort to be paroled. As for Brown, he was off the hook, having died a rich man two years earlier.

As for the Water Tower, Brown received that contract in 1867 from the Croton Aqueduct Board, which had autonomy from Tweed and other politicians. However, Tweed, who was infamous for inflating costs on innumerable public works projects to benefit himself and his cronies, most notoriously with the “Tweed Courthouse,” gained control of Croton Aqueduct operations in April 1870 while the Tower was under construction. There is some evidence that similar corrupt practices occurred on a modest scale with the Tower. As for that silver model, it seems more likely a gift from Tweed, known for his affection for luxuries, than from workers paid modest wages.

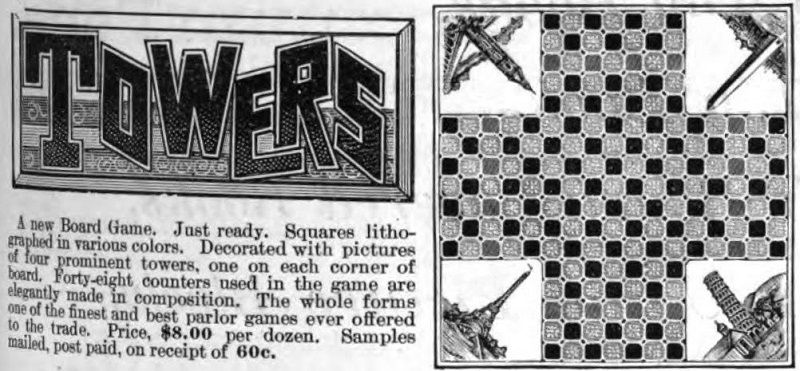

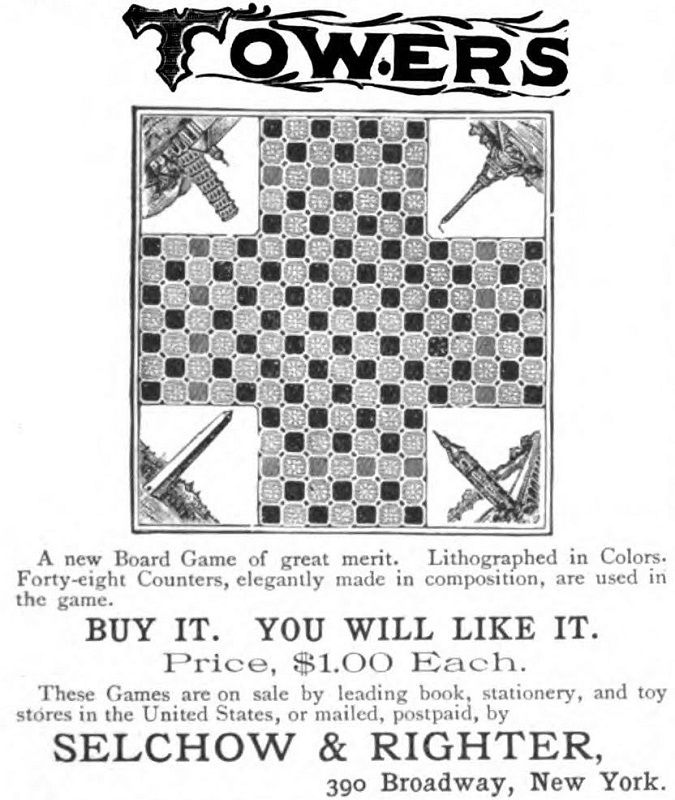

A new game called Towers arrived on store shelves in 1891. Released by Selchow & Righter, a firm better remembered for Parcheesi and Scrabble, this one featured a board with illustrations of the Eiffel Tower, Leaning Tower of Pisa, Washington Monument, and the Highbridge Water Tower.

The trade publication ad above was aimed at businesses, while the one below is from a popular magazine and intended for consumers. Towers sold wholesale for a dozen games at $8 and retailed at $1, putting it at the higher end of amusement options.

Although Towers did not prove to be an enduring classic, its inclusion of the Highbridge Water Tower indicates the Uptown structure’s prominence at the time.

The Tower’s water system operations ended on December 15, 1949 when it was made obsolete by a new electric powered pumping station at 179th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. The City’s Department of Water Supply, Gas, and Electricity planned to raze the old structure, which had become a target of vandals.

In stepped Robert Moses to the rescue. Yes, really. As the New York Herald Tribune reported in 1951, “the Parks Department said it was the intention of Commissioner Robert Moses to save the 170-foot structure as a historical landmark.” The City formally transferred the Tower to the Parks Department in 1955, along with the High Bridge, also removed from water service in 1949, and a section of the Old Croton Aqueduct.

After the Highbridge Water Tower was placed under Parks jurisdiction, the agency teamed up with the Benjamin Altman Foundation to install an electric carillon. This was a device imitating the sound of bells, allowing a building often compared to a medieval campanile to function like one. It debuted on Memorial Day 1958 with a 15-minute performance broadcast on WNYC radio.

The Altman Memorial Carillon, as it was called officially, chimed thrice daily on weekdays and twice a day on weekends for several minutes from speakers mounted in the old tank room. As Gay Talese of the New York Times observed in 1961, it “has served as a combination concert hall and alarm clock with such fidelity that many residents have let it run their lives.”

How long the five-octave carillon continued to operate is unclear. Periodically there has been talk of replacing it, but when members of the Parks and Cultural Affairs Committee of Manhattan Community Board 12 voted on capital project priorities in 2019, there was no support for this.

Undoubtedly the saddest day in the Highbridge Water Tower’s history is June 11, 1984, when a man broke in, set a fire in the tank room, and jumped to his death. This badly burned the cupola, which had wooden framework, destroyed the carillon, and caused other damage.

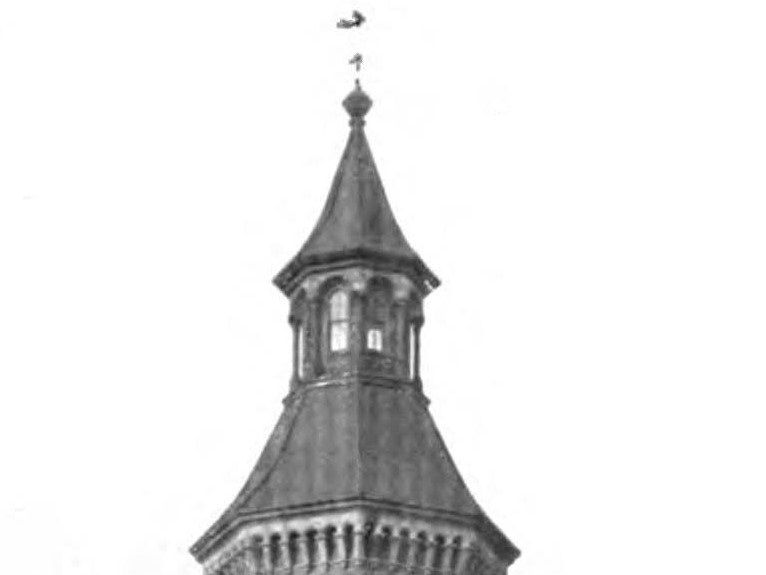

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the Parks Department carried out a restoration, which included a new cupola. Although it looks generally similar to the original, there are aesthetic differences, including louvers in the middle section instead of windows. Also, the replacement weather vane has an arrow, whereas old drawings and photographs show something resembling a mythical aquatic creature.

Today, the cupola is reached via a spiral staircase in the center of the tank room though it is off-limits to the public. On the other hand, the original cupola contained a scenic lookout. A vestige of this are markings on the walls indicating the outline of the stairs that extended above the water tank (photo above).

Find out more about these and other facts and stories at our upcoming virtual talk about the Highbridge Water Tower on March 24th at 12 p.m. The event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. If you’re not a member, join now (new members get their first month free with code JOINUS).

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Highbridge Park.

Contact the author @Jeff.Reuben1

Subscribe to our newsletter