Though New York is known today for its diversity, having been the birthplace of the Harlem Renaissance and the first entry-point for countless immigrants to the United States, the city has a dark past — one tied directly to slavery. “New York… was certainly the major slaveholding state in the North,” said Kenneth T. Jackson, president emeritus of the New-York Historical Society. The sale and ownership of slaves were common in New York City from its founding with the practice abolished statewide in 1827 (complete abolition was only achieved in 1841). Slave owners such as William Dyckman, Peter Stuyvesant, and John Jay were among the most recognizable names in New York City. According to the New York Times, at one point, 40% of Manhattan households owned slaves, mostly Black women doing domestic work.

In 1991, during the construction of Federal Plaza in lower Manhattan, excavators found a six-acre burial ground with over 15,000 intact skeletal remains of free and enslaved Africans who lived in New York during the colonial period. Now designated the African Burial Ground, this public monument serves as a reminder of the city’s often forgotten history of slavery. Just a few blocks south of the monument, Wall Street in the Financial District was the city’s major slave-trading market. In fact, New York had the second largest slave market in the country, second only to Charleston.

To expose the legacy of slavery in New York City, independent artists, educators, and researchers Elsa Eli Waithe, Maria Robles, and Ada Reso formed Slavers of New York. Using historical data and public art, Slavers of New York aims to educate New Yorkers about the city’s history of slavery to encourage public atonement through knowledge.

As the American novelist Ralph Ellison once stated, “perhaps more than any other people, Americans have been locked in a deadly struggle with time, with history. We’ve fled the past and trained ourselves to suppress, if not forget, troublesome details of the national memories.”

Drawing inspiration from The New York Times’s The 1619 Project, Slavers of New York builds on the concept of “collective memory,” which, as defined by French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, is a mode of memory carried out by social groups within society that contributes to collective identity. Memory is crucial because of its transformative capability to change the way an individual or group selects, interprets, and represents historical events in the present. Therefore, providing historical context to public spaces where it is absent allows for collective memory to be transformed and for the legacy of slavery to be confronted head-on.

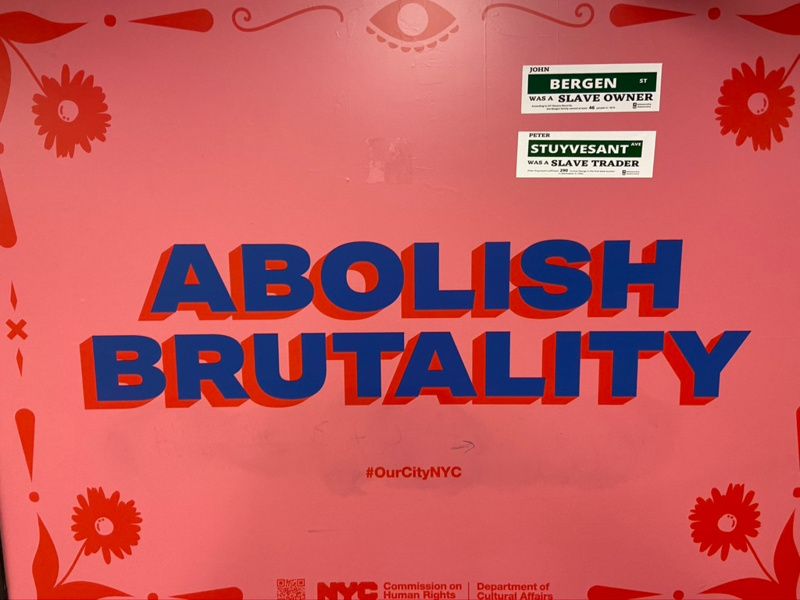

Just as organizations like the New York Antislavery Society reminded New Yorkers through pamphlets and speeches about the city’s issues with racism during the abolition movement, so too does Slaves of NY in the present. Since its inception in 2020, Slavers of NY has placed over 2,000 stickers around Brooklyn and Manhattan — containing information on the hidden history of the city’s streets, neighborhoods, and landmarks named after slave owners.

The stickers imitate the style of NYC street signs, with the names of past enslavers fashioned as current street names. One example is Bergen Street, which was named after the nineteenth-century congressman Teunis G. Bergen, whose family owned at least 46 slaves in 1810. Found on street poles, subway station signs, and public statues, Slavers of NY’s stickers are easily viewable by pedestrians and encourage New Yorkers to learn more about their local communities. To further increase awareness, the organization also has Twitter and Instagram pages dedicated to spreading more historical data on the history of slavery.

In addition, Slavers of NY has created a map of over 500 locations throughout the five boroughs named for more than 200 documented slave-owning families using census records, slave schedules, and newspaper archives. The organization is working to craft an additional map on places named after abolitionists and historical figures whose work attempted to promote American ideals of liberty and justice for all. For the future, the organization hopes to spread its stickers across the remainder of New York City and transform its maps into publicly accessible digital versions that users will be able to interact with.

Next, check out How New York’s Slavery History Is Still Present in NYC.