New York’s most famous Beaux-Arts buildings may be grand civic spaces like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Grand Central Terminal, and the New York Public Library, but the city also has a number of Beaux-Arts mansions constructed during the Gilded Age. During that period, the Beaux-Arts style was the style du jour, and the city’s wealthiest tycoons hired renowned architects like Richard Morris Hunt and Stanford White to design lavish homes that drew inspiration from European palaces and monuments.

Beaux-Arts mansions such as the Petit Château built in 1882 by Richard Morris Hunt for William Kissam and Alva Vanderbilt set the precedent for other Beaux-Arts buildings, including the aforementioned civic buildings. “A combination of European style and American vitality, it became the prototype of a new architectural style—which also had its roots in France—that was to form the basis of virtually all buildings in New York City for the next fifty years,” Phillip James Dodd writes in the introduction to An American Renaissance: Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York City, referring to the Petit Château, which was built in the style of a Loire Valley castle.

Many of those Beaux-Arts mansions, including the Petit Château and the Vanderbilt Triple Palace, were later torn down, but fortunately, some of them still remain. We’ve rounded up ten gorgeous Beaux-Arts mansions in New York City that you can still admire today.

1. Andrew Carnegie’s Mansion

Steel magnate Andrew Carnegie rose up from humble origins to become one of the wealthiest Gilded Age tycoons in the U.S. Born in Scotland, he immigrated with his family at the age of 13 and settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. A voracious reader and ambitious young man, Carnegie worked his way up to a superintendent on the Pennsylvania Railroad at just 24 years old. By the time he was 30, he had business interests in railroads, steamers on the Great Lakes, iron works, and oil wells. He eventually built Carnegie Steel Corporation into the world’s largest steel manufacturing company.

Carnegie was already 63 when he purchased several plots of land on and around East 91st Street and Fifth Avenue on the Upper East Side, and he deliberately sought out land far north of where his peers were living on so-called Millionaires Row. He hired the firm of Babb, Cook & Willard to design a spacious 64-room mansion with a large enclosed garden where he and his wife could raise their daughter. Done in the English Georgian style and completed in 1902, it was the first private home in the U.S. to have a structural steel frame and one of the first in New York City to have an Otis elevator.

Carnegie spent his retirement working out of the office in this mansion to oversee his many philanthropic efforts, donating some $350 million toward the creation of libraries, support of cultural institutions, and the promotion of world peace. Undoubtedly one of New York’s most beautiful Beaux-Arts mansions, it’s now home to the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

2. Henry Clay Frick’s Mansion

When Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick moved to New York City in 1905, he initially rented one of the Triple Palaces built by Henry Vanderbilt, but when his partner-turned-rival Andrew Carnegie built a fabulous mansion on Fifth Avenue (now the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum), Frick was determined to one-up him. He hunted for the most prominent location on Millionaires Row and hired Thomas Carrère of Carrère and Hastings to build him a grand mansion inspired by Parisian hôtel particuliers, which he would fill with his art collection — one of the finest in the world.

Carrère drew inspiration from the Hôtel de Soubise in Paris and created a dramatic layout of rooms with enfilades leading to the garden, the courtyard, or a particular work of art. Frick then hired British decorator Sir Charles Carrick Allom to design the interiors, which feature paneled walls, cornices, and grand fireplaces. He created a whole room dedicated to Fragonard, filled with 14 panels that the artist had painted for Madame du Barry, Louis XV’s mistress. Frick bequeathed the mansion and his incredible collection to the city upon his death and to this day it’s one of New York’s finest art museums as well as one of the city’s most impressive Beaux-Arts mansions.

3. J.P. Morgan’s Mansion & Library

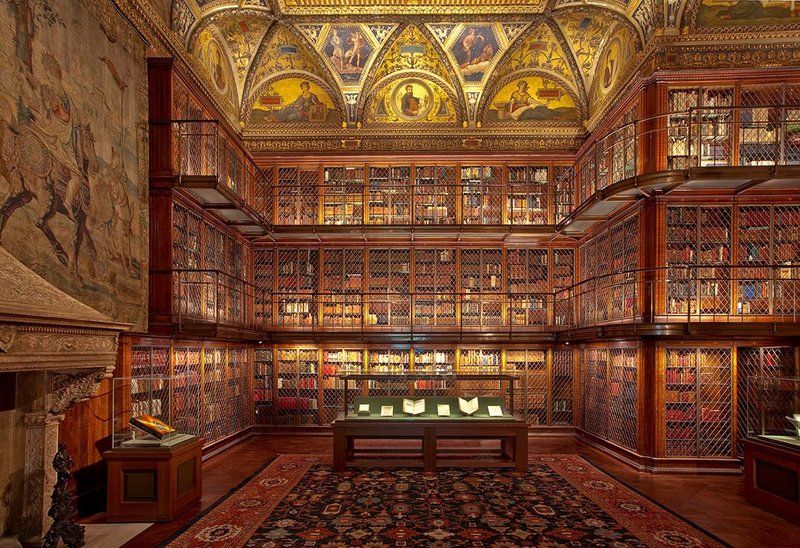

A contemporary of Carnegie and Frick, John Pierpont Morgan was the Gilded Age’s most powerful financier, which earned him the nickname “the Napoleon of Wall Street.” Unlike many of his contemporaries, he wasn’t interested in living on Millionaires Row or flaunting his wealth. He preferred to use his considerable fortune for philanthropic endeavors and to amass an incredible collection of European art and books, with the goal of turning New York City not just into the financial capital but also the cultural capital of the United States.

By 1900, his Murray Hill residence had become overcrowded with his art, so he purchased the two adjacent properties and convinced Charles McKim to design his new home by agreeing to finance McKim’s passion project, the American Academy in Rome, for life. A master architect with myriad influences, McKim designed an Italianate home and library, taking inspiration from a number of Renaissance palazzos, including Villa Giulia and Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome as well as the Palazzo del Te in Mantua. The interiors are richly decorated with marble, lapus lazuli columns, mosaics, damask wall coverings, and lavishly painted ceiling frescoes. After his death, Morgan’s son Jack fulfilled the wish left in his will that his library be turned into a museum.

4. Samuel Tilden’s Mansion

The stately Greek Revival townhouse that now houses the National Arts Club was once home to Samuel Tilden, who was elected governor of New York in 1875 after taking down the infamous William “Boss” Tweed. After winning 51% of the popular vote but losing the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes, Tilden retreated to his home and focused on renovating it. He hired Calvert Vaux to combine two adjacent townhouses into one palatial mansion overlooking the prestigious Gramercy Park, which was inspired by the residential squares and private parks of London.

Vaux set about combining the two homes, modernizing the façades, creating lavishly decorated interiors, and adding an escape tunnel for Tilden, who feared retaliation from Tweed’s associates. He decorated the façade with elaborate carvings of leaves and a decorative panel sculpted with busts of Tilden’s favorite authors, including Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe, and Dante. The interiors feature dark walnut boiserie and carved wood fireplaces, but the crowning achievement is the cove domed ceiling by Donald McDonald made with small pieces of yellow, gold, and white glass and inspired by Islamic geometric designs.

5. Joseph De Lamar’s Mansion

Compared to other Gilded Age tycoons, Joseph De Lamar was a bit mysterious. Born in the Netherlands, he worked on a steamship in order to come to America to make his fortune. He struck it rich mining for copper, nickel, and silver in California, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, and Canada before moving to New York in the early 1890s with ambitions of joining New York’s high society. He built a home in Newport, bought a yacht, and joined all the important private clubs before turning his attention to finding a wife.

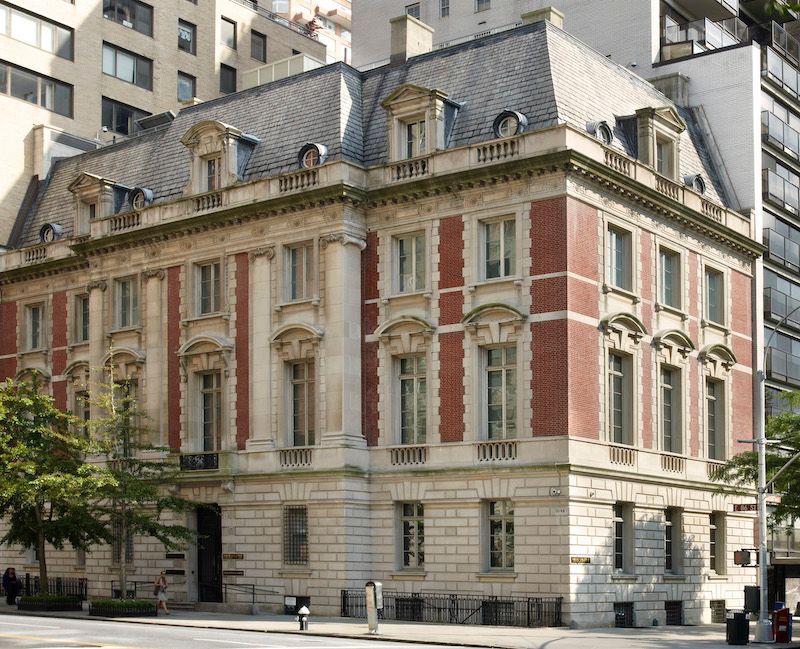

As Dodd explains in his book, De Lamar’s choice of location was a bit unexpected, as by then most of the prominent members of New York society had moved uptown to Millionaires Row on Fifth Avenue. But it seems that J.P. Morgan had slighted De Lamar and so he hired C.P.H. Gilbert (not to be confused with Cass Gilbert) to design a home “that would literally cast a shadow over the house of Morgan.” Gilbert designed the seven-story home in the French Beaux-Arts style with a dramatic mansard roof and elaborate decorative flourishes.

Inside, the home had a billiards room, wood-paneled library, dining room, grand ballroom, and the Pompeian room where De Lamar had his art gallery. He commissioned Louis Comfort Tiffany to create beautiful stained glass panels and equipped the mansion with technology like Otis elevators and an electric hoist that would lower his car into a subterranean garage. Other unique features include a gymnasium and a dog run hidden below the mansard roof. Today the mansion is home to the Consulate General of Poland.

6. James Burden’s Mansion

The stately mansion at 7 East 91st Street, between Fifth and Madison Avenues, was built as a wedding present for Adele Sloane, a great-granddaughter of “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt, upon her marriage to James Burden, heir to his family’s ironworks in Troy, New York. Their lavish wedding in the Berkshires was attended by Richard Morris Hunt, who likely would have been hired to design the mansion had he not died just a couple of weeks after the wedding. Instead, the commission went to Whitney Warren of Warren & Whetmore.

Warren went to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts and returned ten years later. He designed a mansion described aptly by Dodd as “a French interpretation of an Italian palazzo.” Unlike most Gilded Age mansions, which had the “piano nobile” entertaining rooms on the second floor, Warren put the piano nobile on the third floor, so guests had to climb two floors of the oval grand staircase topped by a dome and adorned by a stained glass window by Tiffany Studios. On the third floor is a ballroom inspired by the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, a reception room, and a banquet room in the Louis XIV style. The mansion now houses the Convent of the Sacred Heart Catholic school for girls.

7. Otto Kahn’s Mansion

One of the grandest Beaux-Arts mansions, and the last Gilded Age mansion built in New York City, was the home of wealthy investment banker Otto Hermann Kahn. Born into a distinguished German-Jewish family, Kahn left Germany for London and then New York. He built Oheka Castle on Long Island—the second largest private home ever built in the U.S.—a villa in Palm Beach, and finally this mansion on East 91st Street on the Upper East Side.

Kahn hired British architect J. Armstrong Stenhouse and C.P.H. Gilbert to design his opulent mansion. Stenhouse based it on the 16th-century Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome. The top floor was designed as a private penthouse in the Roman garden villa style, complete with arched loggia and fountains, which served as an art studio for the artists Kahn sponsored. A generous patron of the arts, Kahn loved to entertain, and was friends with Enrico Caruso, George Gershwin, and Anna Pavlova, who gave recitals in the palatial ballroom. From his private quarters on the third floor, he would look down through a discreetly placed window to watch his guests gathering in the Gothic Room to admire his art collection before making a dramatic entrance. The mansion was joined with the Burden mansion to form the campus of the Sacred Heart Catholic school for girls.

8. William Payne Whitney’s Mansion

Born into the illustrious Whitney family, William Payne Whitney inherited a fortune from his father and uncle and had investments in banking, tobacco, railroads, mining, and oil. When he married Helen Julia Hay, the couple received this mansion designed by famed architect Stanford White as a wedding present.

Designed in the high Italian Renaissance style, the five-story mansion features a rotunda framed with marble columns surrounding a fountain, atop which sits a marble statue thought to be an early work of Michelangelo. For the intimate receiving room off the rotunda, White looked to Renaissance Venice for inspiration, creating a Venetian room with mirrored panels, gilded elements, and 18th=century European furnishings. Upstairs are a series of elegant reception rooms. Today the mansion houses the Cultural Services of the French Embassy and the beautiful French bookshop Albertine.

9. Henry Villard’s Townhouses

Born in Germany, Henry Villard immigrated to the U.S. in 1853 and became a prominent journalist and war correspondent reporting on the Civil War for the New York Herald and the New York Tribune. He purchased The Nation and the New York Evening Post before investing in railroads and steamships and eventually merging the Edison Lamp Company and Edison Machine Works into the Edison General Electric Company.

Villard commissioned Stanford White to design six townhouses on Madison Avenue at East 50th Street, which were completed in 1909. Designed in the Italian Renaissance style, the townhouses form a U shape around a courtyard that was meant to provide a space for carriages to turn around. White drew inspiration from the Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome, among other 16th-century palaces. According to a report by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, “Nowhere in New York City does there exist another unified group of brownstone residences of such magnitude as this cluster standing on Madison Avenue.” The Villard Houses are now home to the luxurious Lotte New York Palace hotel.

10. William Starr Miller II’s Mansion

William Starr Miller II was a Gilded Age industrialist who married Edith Caroline Warren, whose brother was architect Whitney Warren of Warren & Whetmore. Though Whitney Warren designed the couple’s Newport mansion, the couple hired Carrère & Hastings to design their mansion on Fifth Avenue.

Completed in 1914, the elegant Beaux-Arts mansion was inspired by 17th-century Parisian architecture, in particular the Place des Vosges. An oak-paneled drawing room and Edith’s bedroom were inspired by Louis XVI style. Edith lived in the mansion until her death. It was then inhabited by Grace Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt III, until her death in 1953. One of the most beautiful Beaux-Arts mansions on Museum Mile, it’s now home to the Neue Galerie, which is dedicated to German and Austrian art, and was renovated by renowned architect Annabelle Selldorf.

Next, read about 10 gorgeous Beaux-Arts buildings in NYC!