Located on the northernmost tip of the borough, St. George is considered one of the primary gateways for people traveling between Staten Island and the rest of the city. The area was first inhabited by the Lenape Native Americans, who moved around quite a bit but stayed in St. George during the summer seasons to fish. It later came under Dutch control as part of the New Amsterdam colony until it was eventually purchased by the British in 1664. Many of its first settlers were a mixture of Dutch, British, and French people who didn’t necessarily have a name for the location.

The northern part of the island saw a great deal of development mostly towards the beginning of the 19th century due in large part to the efforts of Daniel D. Tompkins, former New York State governor and U.S. Vice President to James Monroe. His purchase of the farmland in St. George ended up having a significant influence on the street layout in years to come as more land developers followed in his footsteps.

The neighborhood is considered a high-income area on Staten Island and consists primarily of Black and Hispanic residents. Despite the borough being the only one to have a predominantly White European American demographic, St. George is indicative of the ever-increasing minority population in New York City over the past few decades. The neighborhood features businesses of varying ethnic backgrounds from Thai to Italian in its bakeries, restaurants, and convenience stores. From the origin of its name to a beloved restaurant serving multi-cultural cuisine, here are ten fascinating secrets of St. George.

1. “St. George” was not actually a saint but rather a land developer

The neighborhood got its name during its developmental years in the late 1880s, when much of the land on Staten Island close to New York Harbor was still a summer retreat for wealthy New Yorkers like the photographer Alice Austen, who lived further south in Rosebank. The area now known as St. George was originally considered part of New Brighton, the neighborhood west of present-day St. George.

A businessman named Erastus Wiman was looking to acquire the land in order to construct a new rail-ferry terminal, so he asked a railroad engineer and financier named George Law to purchase it. Law was involved with the contracting for several public works projects in the United States, but specifically in New York, where he notably took part in the contracting for the High Bridge. Because Law was able to obtain the waterfront property in New Brighton at a bargain, Wiman promised to “canonize” George Law and name the area after him.

2. The St. George Terminal is one of the few rail-boat connections left in the United States

Planning for the St. George Terminal began in the 1870s, when developers were looking to organize the various ferry ports along the waterfront into one centralized dock. St. George was selected as the terminal’s location because it was the shortest distance from the Whitehall Street ferry terminal in Lower Manhattan. The Staten Island Ferry terminal was completed in March 1886, while the train station underneath it opened a year later. The Staten Island Railway line was owned and operated by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company until the MTA decided to create a separate subdivision of the subway system and took control over Staten Island Railway operations.

The terminal underwent some significant changes after the MTA’s construction of the Staten Island Tunnel in the early 1900s, as well as a fire that completely destroyed the terminal in 1946. The tunnel was part of a project that would connect the rail line on Staten Island to the BMT Fourth Avenue Line running just across the Narrows in Brooklyn. Although significant progress was made, construction was discontinued due to a lack of funding. A fire a few years later exposed flaws in the terminal’s layout, leading to a complete $21 million redesign in 1951.

3. Several buildings were designed by Carrère & Hastings

The Carrère and Hastings architectural firm was responsible for quite a few Beaux-Arts constructions in New York City. John Merven Carrère and Thomas Hastings collaborated on projects such as the main branch of the New York Public Library, the interior of the Metropolitan Opera House, the Frick House, and the Standard Oil Building in the Financial District. Their contribution to architecture came in the realm of urban design, aiming to beautify city life while implementing centuries-old architectural styles.

The St. George Library Center, Staten Island Borough Hall, and Richmond County Courthouse are the three structures in the neighborhood that were built by the Carrère and Hastings firm. The French Renaissance-mixed Borough Hall was built in 1906 and serves as the primary municipal building for the borough. The Neoclassical style of the courthouse is characterized by its pillars at the front, while the Library Center features timber-beamed ceilings with a clear view of New York Harbor from its windows.

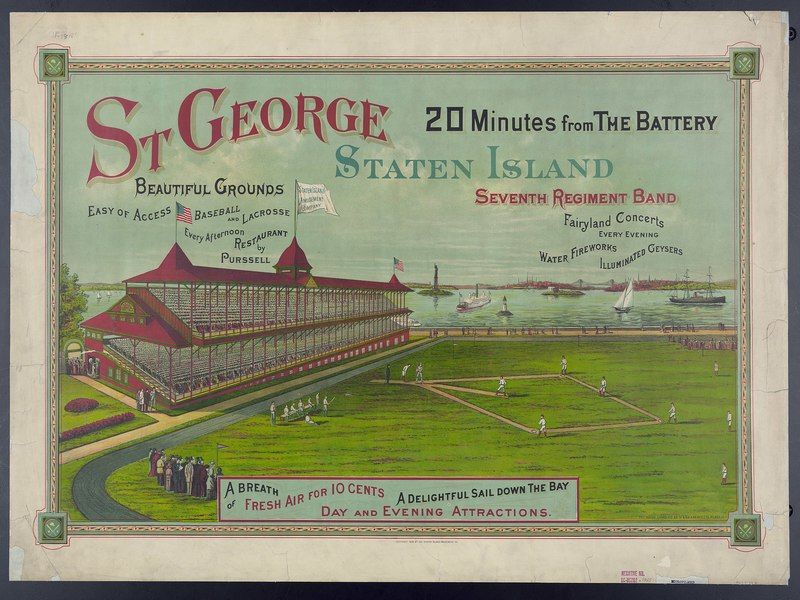

4. An amusement park used to exist in St. George

Wiman’s Staten Island Amusement Company operated along the waterfront in St. George with the help of the Staten Island Railway in the late 1880s. Residents from different parts of the island would come to concerts, band shows, circuses, sporting events, and even shows featuring live animals. The attractions also coincided with the St. George Cricket Grounds, which used to be the former home stadium of the New York Metropolitans, a baseball team from the Major League’s earliest years.

Despite the attention these brought, the commuter-style atmosphere of St. George ultimately gave the amusement park a short lifespan. Companies were beginning to head out onto Long Island, where destinations were more exclusive and marketable to customers, especially during the summer.

5. The headquarters of the United States Lighthouse Service was located here

The building that now houses the National Lighthouse Museum used to be part of the general depot for the United States Lighthouse Service (USLHS) and served as a headquarters for the agency. Also known as the Bureau of Lighthouses, the agency was established in 191o with the purpose of maintaining and regulating lighthouses in the United States. The building itself was constructed on the site of a former hospital in 1862 and became a key storage facility for maintenance materials used by the USLHS. Vaults within the building contained equipment such as lamp oil, lenses, ship anchors, chains, paint, and other maintenance materials.

The facility started to decline after the property was handed over to the U.S. Coast Guard in 1939. The United States entered World War II a few years later, and the site was utilized as a repair center and painting facility for marine vessels used during the war. Once the Coast Guard moved its headquarters over to Governors’ Island in the early 1960s, coupled with the decreasing need for lighthouses, the facility’s condition worsened even further. The abandoned location became vandalized and worn down until the 1980s, when the building became a designated New York City landmark.

6. The “Staten Island Quarantine War” took place in St. George

The site of the former USLHS storage depot was actually a controversial quarantine hospital called the New York Marine Hospital. The city was going through an outbreak of yellow fever that killed thousands of people at the start of the 19th century. In response to the growing issue, the city decided to construct this hospital on Staten Island that would house people who were believed to be infected with the disease. The decision to place the hospital on the island caused serious backlash from those who lived in the area due to fears of outbreaks and poor containment.

These fears did come true as small outbreaks began to occur among exposed workers who would come in and out of the facility every day and walk through St. George. Residents were furious and threatened to burn down the facility, but in response, the city shut down the Staten Island Ferry. On the 1st and 2nd of September 1858, residents stormed the hospital and burned down the buildings in the complex. Armed forces and battalions had to be called upon to handle the chaos in the days following the initial attacks and made subsequent arrests for the leaders of the uprising. One of those leaders was Ray Tompkins, the grandson of former New York Governor Daniel D. Tompkins.

Those who were arrested and brought to trial were set free because the judge deemed the crimes legitimate acts of self-defense. The people of St. George and the communities surrounding the New York Marine Hospital acted in response to what was a serious health hazard. The event played a crucial role in questioning the ethics behind quarantine hospitals in the United States and how effective they actually were at treating patients and containing outbreaks. The hospital was closed, but quarantine facilities were moved to locations such as Swinburne and Hoffman Islands, where infected patients would be away from populated areas of the city.

7. Houses in St. George feature a wide range of architectural styles

Plenty of the homes around Curtis High School and in the Fort Hill section of the neighborhood used to be summer-getaway destinations for wealthy Americans in the early 19th century. Daniel D. Tompkins, Anson Phelps Stokes, a wealthy merchant and philanthropist, and Belmont Stakes founder August Belmont owned much of the land and had their families and friends living in the surrounding area as well. The majority of the houses that still remain were constructed in the 1880s and ’90s and add a distinct quality to the neighborhood.

The streets were laid out on hills, which meant construction had to be done in a manner that would require steps leading down from each porch onto the sidewalk and road below. A lot of the homes feature Victorian and shingle-style architecture, while there are two remaining Greek-revival homes closer to the waterfront portion of St. George. Tudor and Colonial Revival houses are also located in the St. George Historic District, which was officially designated by the city in 1994. Art Deco is another style on display at the Ambassador Arms apartment building on Daniel Low Terrace. The building was a temporary home for actors Paul Newman and Martin Sheen and stands out from most other buildings in the area with its gold and blue terra cotta trim.

8. Richmond County Bank Ballpark was built over a former rail yard

The 7,171 seat baseball stadium is located to the west of the shopping center near the St. George terminal and was the home of the Staten Island Yankees. The minor league team had been playing their home games at the park since 2001, but stopped in 2020 when the New York Yankees decided to disband the team. The stadium is currently undergoing a $5 million renovation to install new turf and reshape the field so that it can accommodate games for local rugby and soccer teams.

The site of the stadium itself used to be a rail yard utilized by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in the 1880s. The St. George Yard was where most of the freight transported across the island would be loaded onto ships to be carried out of New York Harbor. It remained as such until the St. George terminal fire of 1946 forced significant changes onto the surrounding facilities. The terminal’s renovation gave the Department of Transportation the opportunity to introduce a park-and-ride option to commuters looking for a more accessible way to go to work in the city without having to rely completely on public transportation. Thus, the city decided to build the parking lot over a part of the railyard, which was followed by Richmond County Bank Ballpark some decades later.

9. The St. George Theater was designed to rival some of the premier theaters in New York City

The 2,800-seat performing arts center opened in 1929 and was built in honor of Solomon Brill, who owned a number of movie theaters on Staten Island and in the New York metropolitan area. It began as a movie theater and was not used as a stage for any other type of performance until the 1950s, when theater owners began to diversify the kinds of performances and integrate both films and live acts together. Musical icons like Chaka Kahn and Lester Flatt, as well as comedians Chris Rock and Jerry Seinfeld, performed at the St. George Theater.

The theater’s main architect was Eugene De Rosa, who alongside fellow architect Nestor Castro integrated a captivating Spanish and Italian Baroque revival-style design to the interior of the theater. Along with the incorporation of gold plasterwork on the walls, velvet seats, stained glass, and intricate staircases, the designers looked to perfect the acoustics of the showroom. The sound was contained in a way that enabled the performers on stage to project their voices without requiring much more effort than if they were to have a conversation with someone from across a room.

10. At Enoteca Maria, grandmas from around the world run the kitchen

One restaurant that represents the blending of cultures in St. George is Enoteca Maria on Hyatt Street, right next to the St. George Theatre. Grandmothers, or “Nonnas”, are the chefs at the restaurant, collaborating to cook and serve unique dishes to customers. Enoteca Maria was originally just an Italian restaurant, but since 2015 they began hiring cooks from different ethnic backgrounds and serving a variety of dishes. Parts of the menu change each day, but foods from Argentina, Azerbaijan, Pakistan, Puerto Rico, and many other countries are served here. Enoteca Maria is only open on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays and was founded by the current owner Jody Scaravella, who was born and raised in Brooklyn.

Scaravella was looking to provide customers with the feeling of home when he came up with the idea for his restaurant. The concept of using grandmothers as cooks was inspired by his Italian grandmother Nonna, whom he would remember going to the market with and watching her pick out fruits and vegetables to cook at home. Not only did he realize that his grandmother was a symbol of cultural preservation in his family, but he also understood that cultural diversity in his community was just as significant.

Next, read about the top 10 secrets of Astoria, Queens!