Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Preservation League of New York State has released their annual “Seven to Save” list of 2022-2023. For more than 20 years, the Preservation League has been publishing an annual list to highlight the most endangered sites in New York state. In order to qualify, each site must be architecturally, culturally, or historically significant, though it doesn’t necessarily have to be landmarked, and its continued existence or integrity must be threatened. In addition, there must be a strong local group advocating for the site’s protection and a leader who can work with the League to determine how it can play a meaningful role. It’s an added bonus if the site represents a broader regional, state, or national preservation issue. Without further ado, here are the seven sites on this year’s list.

It’s no surprise that the area surrounding Penn Station is on this year’s “Seven to Save” list. Vornado’s Empire Station Complex plan aims to redevelop the blocks surrounding the station into glassy office and commercial buildings. Forty historic buildings and structures are at risk of demolition and thousands of residents and businesses are set to be displaced. The historic Hotel Pennsylvania designed by McKim, Mead & White is already being demolished and many other historically significant buildings are at risk, including the Penn Station Powerhouse.

The destruction of historic buildings surrounding Penn Station is especially ironic, as the demolition of the original station by McKim, Mead & White was the very thing that birthed the preservation movement in New York City. Referring to the Empire Station plan, our Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers wrote, “Of course, New York wants a better transit hub but I, like many, advocate for a thoughtful station rehabilitation that integrates the historical structures within and around it.”

Rampant development is threatening the historic character of parts of the East Village and Greenwich Village south of Union Square. While adaptive reuse has seen factories, schools, rowhouses, lofts, firehouses, and recording studios get converted into condos, shops, theaters, restaurants, and university classrooms, the neighborhood lacks landmark protections.

“How many neighborhoods can claim to have been central to the struggles for African American and LBGTQ+ civil rights, as well as the Women’s Suffrage movement, while also housing some of the most important artists, writers, dancers, sculptors, publishers, and recording studios of the last century and a half?” Andrew Berman, Executive Director of Village Preservation, said in a statement. “Sadly that rich history is gravely endangered by a rising tide of demolitions and oversized development. We hope this designation will help spur the new Mayoral administration to finally act to protect this irreplaceable history, so central to the story of New York and our country.”

The Brooks-Park home in East Hampton has been gaining both the regional and national spotlight lately, as it was included on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s annual 11 Most Endangered list. James Brooks and Charlotte Park were abstract expressionist artists in the 1940s and ’50s. Though not as well known as Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, whose East Hampton home and studio has been preserved by Stonybrook University as the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, James Brooks gained acclaim for painting the largest site-specific WPA wall mural, located at LaGuardia Airport’s Marine Air Terminal.

The 11-acre site comprises four buildings: Brooks’ studio, a midcentury vernacular structure that he designed and built himself; Park’s studio, which was reportedly originally a post office; and the couple’s home and guest cottage, which were moved via barge from Montauk after their studios were damaged in a hurricane. The buildings have been abandoned since Park’s death in 2010. Though the town of East Hampton purchased the site in 2013 using Community Preservation Funds, little has been done to stabilize or protect the buildings, which are being threatened with demolition.

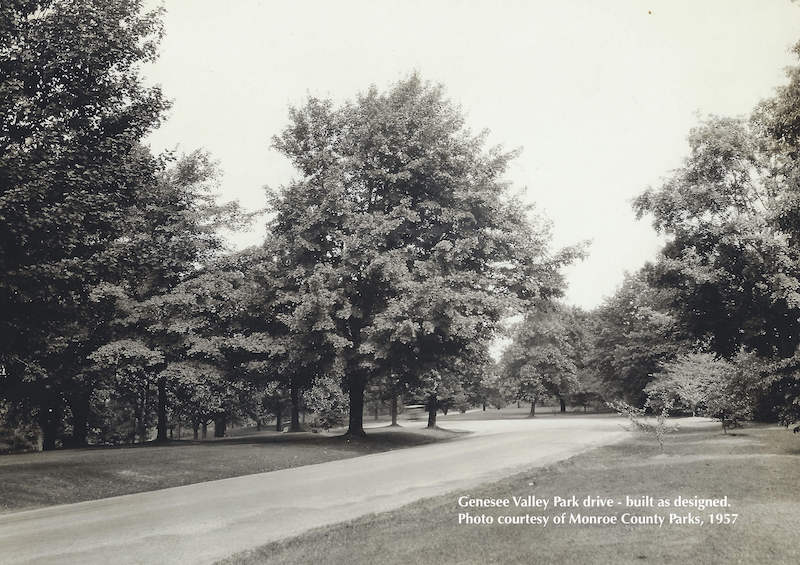

Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, whose bicentennial year is being commemorated this year, Genesee Valley Park is being threatened by the University of Rochester. Created in 1890, the park is publicly owned by the city of Rochester, but a stretch of woodland bordering the Erie Canal that formed part of the park’s original design is owned by the University of Rochester, which wants to clear over an acre and a half in order to build a warehouse. Even if the plan doesn’t go through, the site remains subject to development by the university.

“We wish to acknowledge the historic designed landscape of Genesee Valley Park as vital to the scenic quality of the river corridor and to celebrate it as part of our Olmsted heritage,” JoAnn Beck of the Rochester Olmsted Parks Alliance said in a statement.

Opened in 1869, Willard State Hospital — also known as Willard Asylum for the Chronic Insane — was the largest of its kind in the 1870s. Once spread out over 1,000 acres, it comprised dozens of buildings, open space, and working farms. According to Atlas Obscura, it was “intended to be a better alternative to systems in place for taking care of the mentally ill.” Patients walked about freely, tended to the farm, and took part in activities like sewing classes. There was even a movie theater and bowling alley on the complex in addition to facilities for electro-shock therapy and ice baths.

Following a 1972 exposé on the horrendous conditions at Willowbrook Asylum, many psychiatric hospitals were shut down in favor of outpatient treatment methods. Willard remained open until 1995, when it shuttered its doors for good. It was then repurposed by the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, which restored some of the historic buildings but neglected others before announcing in 2021 that it would be closing the facility. The Preservation League and Romulus Historical Society hope to preserve the hospital complex before it deteriorates past the point of no return.

In Jefferson County, not far from the Canadian border, is the Thomas Memorial AME Zion Church, which stands as a testament to the struggles and triumphs of the area’s African American community. After forming a congregation in 1878, the church was built in 1909 by its members, many of whom were formerly enslaved railroad workers. Some were active abolitionists, giving the church a connection to the Underground Railroad.

The church has lacked a caretaker since 2017, but a coalition has formed to advocate for its preservation and reuse. “The church is an important attribute to the city of Watertown as well as to the entire North Country. It serves as a focal point for documenting the history of the local African American community,” Shameika Ingram, Founder of Preservation in Color, said in a statement.

Located in upstate New York, the small city of Oneonta is one of the northernmost cities in the Appalachian region. For more than 200 years, the Downtown Oneonta Historic District has been a center of economic activity and urban development. Many of its commercial, converted residential, and civic buildings remain intact. Yet like many small cities with dwindling populations, Oneonta suffers from disinvestment and rural poverty.

“Oneonta’s Downtown Historic District is not just a business district, it is representative of generations of hopes and dreams, it is an investment made by those who came before us and one that we will leave for those who come after,” Stephen Yerly, Deputy Community Development Director for the City of Oneonta said in a statement. “Historic preservation is collective memory and valuing the experiences and places that have shaped us and will continue to shape future generations.

Next, read about 30 abandoned places in New York City!

Subscribe to our newsletter