How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

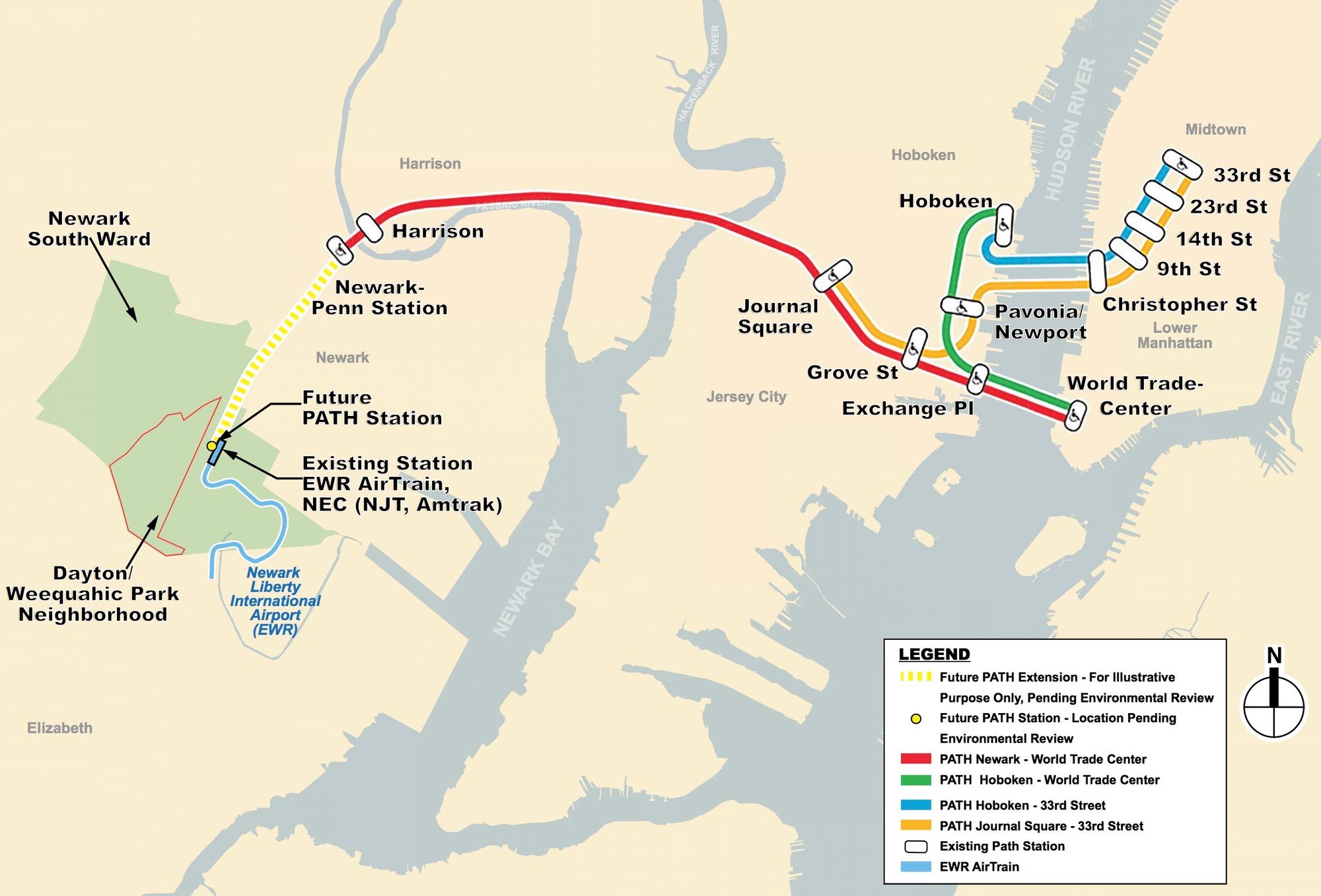

Buried beneath the streets of New York City and its surrounding waterways, interspersed among the labyrinthine subway tracks, are the tunnels of the Hudson & Manhattan (H&M) railroad – known today as the PATH train. For those unfamiliar with the PATH, it’s the commuter railway connecting New York City’s so-called “sixth borough” – the New Jersey Gold Coast, comprised primarily of Jersey City and Hoboken – with the urban centers of Manhattan and Newark, NJ. The PATH train generally operates in four lines during weekdays and two on weekends, spanning from Newark to World Trade Center, Hoboken to World Trade Center, Hoboken to Manhattan’s 33rd Street and Jersey City’s Journal Square to 33rd street.

Weathering many of the same storms as its MTA counterpart, from strikes and budget issues to tropical storms and train traffic incidents, there are some secrets even the most seasoned traveler crossing the Hackensack and Hudson rivers may have missed. Diving into the top 10 secrets of the PATH train, it’s best to begin with the history of the tunnels themselves.

The island of Manhattan was connected via rail with Northern NJ for the first time on February 25th, 1908, but at that point plans for the connecting trains were over thirty years old. Hudson & Manhattan (now PATH) railroad tunnels originated with plans from the 1870s, but these construction outlines were hampered by technological and engineering constraints of the time. The first train finally departed New Jersey through the clean tunnels, slowing to a roll below the Hudson river before arriving into New York City. The importance of this frosty Winter day was marked by a telegram sent from President Theodore Roosevelt, himself a New Yorker, announcing the ceremonious start to the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad.

While the New York City subway began running in 1904, four years before the first railcar from New Jersey brought travelers into New York City, the H&M (PATH train) railroad tunnels originated with plans much earlier than the subway’s construction, planned beginning in 1894.

Across the Hudson River, an ornate and historic building juts out along the pier. In Hoboken, NJ the stunning Hoboken terminal railroad building hearkens back to an earlier time when most of New York City’s waterfront served as receiving and shipping stations for freight to and from New York City’s suburban areas to the metropolitan center. (The popular High Line on Manhattan’s western edge also once served this function.) Built by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western railroads in 1907, the structure was designed by architect Kenneth MacKenzie Murchison.

Hoboken’s terminal building is the second busiest in New Jersey after Newark Penn station, and the various buses, light rails, commuter trains, suburban trains and ferries departing the terminal regularly see 50,000 visitors daily. The building is one of the final remaining train structures along the Hudson River waterfront: a common sight two generations ago.

Starting in the mid-20th century, PATH train staff managing the train switchboard directing tracks at the line’s centrally located Newport (formerly Pavonia/Newport) station began to celebrate the Christmas holiday season by placing a small, festive Christmas tree up along a dividing wall were the Hoboken-bound and Jersey City-bound tracks merge. Continuing today, around Thanksgiving time many a PATH train rider eagerly anticipates the arrival of the miniature lit Christmas tree, still secure in its location at the Newport PATH train station and visible to riders entering and leaving the station.

This tradition originated as a string of holiday lights along the Newport train station tunnel, evolving into the lit tree. After the 2001 WTC attacks in New York City, PATH engineers added a United States flag, backlit in the tunnel, in honor of the victims.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center, support came from all corners of the globe. One such show of solidarity arrived from Italy when, in recognition of the tragedy of both the WTC attack and the 1976 Italian Friuli-Venezia Giulia earthquake, artisans from the Mosaic school of Friuli created a mosaic spanning the length of several train cars.

Now installed beneath the elegant Calatrava-built World Trade Center station on PATH train track #1, the mural – entitled Saetta Iridescente (Iridescent Thunderbolt,) and attributed to artist Giulio Candussio, provides a meditative view for passengers awaiting their next train.

In the late 1970s, artist Cynthia Mailman was selected and commissioned to create an expansive artwork for the World Trade Center PATH train terminal. The artist worked for months with apprentices to create a more than 50-foot long visual tableau of scenes PATH riders encountered along their commute. The artwork, titled “Commuter Landscape” featured iconic visions of industry and landscape such as the Pulaski Skyway bridge spanning the Hackensack river and visible to Newark-WTC PATH train riders in their daily commute.

However, the 1993 World Trade Center bombing dashed Mailman’s dreams as her artwork was victim to the attack which destroyed the building’s basement. The artist rushed to the scene when she heard of the attack, only to discover that along with the significant loss sustained at the site, her mural was completely destroyed. While the artist mourned the loss of her work, she joined in solidarity with the survivors of the attack and to honor the victims.

In October of 2012, Superstorm Sandy devastated the New York City area when the storm surge hit a whopping 13 feet high. In our interview with PATH Train General Manager Clarelle DeGraffe, she discussed the topic of capital projects – including recovering after flooding from Superstorm Sandy. The timeline and cost for this recovery was unlike anything leadership had encountered in responding to a natural disaster throughout the PATH’s 100+ year history at the time.

In the wake of Superstorm Sandy, the PATH train system was shut down for a whole week starting in late October 2012, with trains resuming in limited capacity over the next month before returning to its full four routes by the end of the year.

While frequent PATH Train riders know the difference between the ‘Penns, the two Pennsylvania stations that anchor the PATH train system – Newark Pennsylvania Station and New York Penn Station – go by slightly different names along the PATH train line maps to avoid confusing riders. Newark’s PATH train terminus goes by the term ‘Newark Penn Station’ in train announcements, while the terminus for the train lines in Midtown Manhattan, while arriving just next to New York’s own Penn Station, goes by the station name “33rd Street.”

Other train stations have also shifted identities throughout the years. Mostly notably, Jersey City’s Newport Station was previously known as both “Erie” and “Pavonia/Newport” station, while the station stop has confusing architectural features: Corinthian columns flanked by the letter “E.” This E refers to the New York, Lake Erie and Western railroad, which once traversed nearby Pavonia Avenue.

A surprising connection exists between the Goodyear company and the PATH train. In 1954, the company invented a moving walkway which they called the “Speedwalk” which transported passengers more quickly along their commute. A surprising and fast-moving technological innovation, this 277-foot long moving walkway was the first of its kind in the United States.

The pathway moved steadily along at a speed of 1.5 miles per hour with a grade (incline) of up to 10%. This invention set the stage for airport everywhere serving hurrying passengers in the second half of the 20th century.

Famed early 20th century architects McKim, Mead and White were commissioned to build the original Penn Station on Manhattan’s West Side. Completed in 1910, the station lasted less than 50 years before being demolished. But did you know there’s another Penn station, completed by the same architects, just a few miles across the Hudson River.

Newark Penn Station, also commissioned by the Pennsylvania Railroad company and built by McKim, Mead and White, was finished in 1935. Still standing today, it was the iconic firm’s final major construction project. Many of the architectural flourishes and vaulted ceilings shared visual similarities with New York’s own Penn Station. Newark Penn station finally began to see renovations in the past few years, restoring it to its former glory.

After years of deliberation, with proposals advancing five years ago toward the planning stage, the PATH train is finally forging ahead toward a station located at Newark Liberty International airport. Current passengers can take the PATH train to its terminus at Newark Penn station, before changing to board a NJ transit train to the existing AirTrain station at Newark Liberty Airport/EWR.

Currently the country’s 12th busiest airport by foot traffic, the updates to the airport – announced in 2022 – include infrastructure improvements and plans to increase more efficient access to the airport for passengers from across the New York/New Jersey area.

Next, check out our guide to Jersey City’s Liberty State Park.

Subscribe to our newsletter