Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

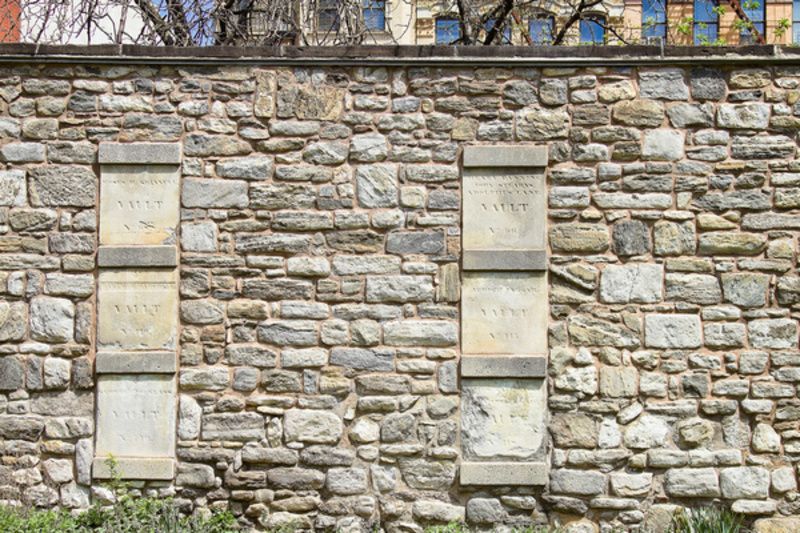

Picture this: A cemetery with underground marble vaults, plaques containing the names of families and vault owners but not the names of burials, and no headstones. Although not what most of us picture when we think of cemeteries, this style was pioneered by one of New York City’s oldest cemeteries, New York Marble Cemetery in the East Village. The historic cemetery, which has housed the likes of New York City mayors, famous architects, and groundbreaking doctors, has even been the site over the years for weddings, corporate garden parties, graduations and movies, which have helped pay for landscaping expenses.

New York Marble Cemetery, which was incorporated in 1831, was New York City’s first non-sectarian burial place open to the public. Confusingly, one block away is the New York City Marble Cemetery, built one year later due to the popularity of the New York Marble Cemetery. The cemetery was organized by Perkins Nichols alongside two lawyers, Anthony Dey and George W. Strong. The location for the cemetery was chosen because it was on the northern edge of residential development, an area with a number of church cemeteries already constructed.

Unlike many cemeteries of lower Manhattan, New York Marble Cemetery features underground vaults as opposed to earth graves. At the time, people feared burying their dead in coffins below ground due to recent yellow fever outbreaks. Additionally, legislation had outlawed earth graves, meaning that marble vaults were the preferred and safest way to bury loved ones. Thus, 156 marble vaults the size of small rooms were erected 10 feet underground, laid out in a grid of six columns by 26 rows. To get access to the vaults, people needed to remove stone slabs, with some requiring keys to open. Instead of markers placed on the lawn, marble plaques along the cemetery’s north and south walls contain the names of the families of the interred; the names of those buried were notably absent.

The vaults were constructed out of Tuckahoe marble, whose name refers to a dolomite mineral vein extending from Connecticut to New York state. A large quarry in Tuckahoe, Westchester, can still be seen. Inwood, Manhattan, was also a notable site of stone mining, with so much stone mined that the quarry became deeper than the Harlem River itself. Because of this depth, the river was rerouted, leaving about 75 acres of Manhattan north of the river today called Marble Hill. The coarse marble, which was commonly used for early 19th-century construction projects, is particularly susceptible to weathering, which is partially why parts of the North Wall collapsed in 1997. The deteriorating Dead House was also demolished over 60 years ago.

Among those interred, the most common causes of death were consumption (TB), still-birth, and scarlet fever. However, the museum’s website lists 145 potential causes of death. About half of the older caskets in the cemetery were for children six and under, since contagious diseases like measles and whooping cough did not have a vaccine yet. Antibiotics were also not available for infections like pneumonia and cholera, and congestion and inflammation were also common causes of death specifically among children. One of the most surprising common causes of death at the time was indeed old age, as many lived into their eighties and nineties.

Almost a decade after New York Marble Cemetery opened, rural cemeteries were gaining traction among New York families. It was common for older remains to be moved out of lower Manhattan and reinterred in these rural cemeteries, even from cemeteries that were still functioning. New York Marble Cemetery lost about a third of its inhabitants to places like Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. By 1851, many churches had already started to sell their church burial grounds

Many of those interred though had been quite successful in their careers. Among those currently or previously buried in the cemetery are Benjamin Wright, Chief Engineer for the Erie Canal; James Tallmadge, Jr., Congressman; Luman Reed, American merchant and art patron; Stevens T. Mason, first governor of Michigan; and Aaron Clark, Whig mayor of New York City.

By the 1880s, the growing population in lower Manhattan thanks to new waves of immigration from Central and Eastern Europe jeopardized the statuses of New York Marble Cemetery and the nearby New York City Marble Cemetery. Social reformer Jacob Riis attempted to turn New York Marble Cemetery into a playground in 1897, and in 1905, the cemetery was almost dissolved had it not raised $21,000 for an endowment. However, some families emptied the vaults due to the cemetery’s still uncertain future. The last burial occurred in 1937, the same year that efforts to find heirs to the vaults was abandoned.

As the cemetery began to fall into disrepair, it was designated a New York City Landmark in 1969 and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980. Official records were deposited at the New-York Historical Society in 1974. From the late 1990s until today, much of the original endowment has been used to restore the gates and walls, as well as to research the burials and living descendants. According to DuBois, the “‘old New York site’ unchanged for nearly 200 years as a private burial ground for wealthy merchants” is now “undergoing ‘adaptive reuse’ as a public gathering space and environmental oasis,” and viewers may get to see the cemetery’s resident red-tailed hawk.

DuBois also mentioned that previous events have included a fashion show by Stella McCartney, a wine tasting to promote Dreaming Tree Winery by Dave Matthews Band, Coca Cola’s introduction of summer spritzers for influencers, and TV shows like Law and Order.

Throughout its nearly 200-year history, New York Marble Cemetery maintained its historic New York City charm, even when in disrepair.

Next, check out 10 Quiet Places to Escape the Noise in NYC!

Subscribe to our newsletter