NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

As one of New York City’s most beloved landmarks, Grand Central Terminal has a storied history known throughout the world. Opened on February 2, 1913 as a replacement for Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Grand Central Station, the terminal quickly became a hub for transportation. Today, Grand Central boasts a slew of restaurants and retail stores intended to serve public and private interests for tourists and residents alike.

Over the years, Grand Central Terminal has stood as a centerpiece in the Tri-State Area. However, not all of the common knowledge about the edifice is true. From the phrase “meet me at the clock/under the clock” not originating from the terminal’s clock to the terminal’s sub-basement not having been a target of Nazi Germany during World War II, Grand Central’s legacy is tainted with stories brewing in misinformation. Untapped New York has been steadily debunking these myths for years, and we have now compiled the many myths for you in this one fun read.

To experience the origins of the myths in person, join Untapped New York for a tour of Grand Central. On this unique walking tour you will discover the history of the Beaux Arts train station, from its glittering glory days to disrepair and modern quests to save it. Our top rated tour guides will make you experience what most miss: its hidden features, design quirks, and more. Read on to learn more about the truth of Grand Central’s greatest myths.

From hidden tennis courts to the remnants of a lost movie theater and an office-turned-speakeasy, uncover the secrets of New York City's iconic train terminal!

One of the most famous myths regarding Grand Central’s clock has been reproduced on numerous websites and television shows. The truth behind the myth — that the clock is worth $20 million — is that the clock is not the “priceless jewel in plain sight” many believe it is. In 2020, Untapped New York detailed the origins of the myth and debunked it, with assistance from the passionate editors of the Grand Central Terminal Wikipedia page, the New York Transit Museum, and others.

The root of this myth comes from the supposed material of the clock face, erroneously said to be made of “solid opal.” This claim can be first traced back to an Associated Press article titled “Celebrating New York City’s Unique Public Spaces which was published on March 7, 1999. Daniel Brucker, the former docent-in-chief at Metro North is also known for having promulgated this myth during off-limits tours he gave of the terminal. The myth spread rapidly online and became a supposed truth. You can follow the spread of the myth in our previous article and read about the efforts of Wikipedia editors and Untapped New York to track down its origins.

Looking back at historical documentation, a 1954 New York Times article reporting on the restoration of the current clock in the atrium describes the faces of the clock as just “glass,” not opal. Later, a 23-page interior landmark designation report written in 1980 on the terminal merely referred to the Main Concourse desk being “topped by a handsome four-faced bronze clock.”

The clock is described as having “opaline glass” faces in Grand Central Terminal: 100 Years of a New York Landmark, the official book for Grand Central’s centennial. From here, it is easy to see where the confusion as to the faces being made of opal might have come from, but opal glass is not made from any opal. With origins dating back to 16th century Venice, opal glass consists of a combination of bone ash, tin dioxide, and antimony compounds, sometimes added to ceramic glass to produce a milky white color. Untapped New York also confirmed with the New York Transit Museum that the catalog record of a damaged clock face located in the museum’s collection resolves all questions: “Opal glass convex circular Clock Face removed from four-sided admiralty brass ball clock.” The convex shape of the clock face is apparent — it is certainly not solid anything, let alone solid opal.

As the legend goes, a bullet-proof, armor-plated Pierce-Arrow limousine transported President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, paralyzed from the waist down from polio, onto his own train car that would then arrive at Grand Central on Track 61. Afterward, the limousine is said to have been driven directly onto the platform and then onto an elevator that rose into the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Unsurprisingly, this fantastical story remains nothing more than a myth. In 2019, Untapped New York debunked it through a detailed investigation.

For years, the MNCW #002 has been photographed and written about at length in reference to its role as FDR’s private train car. Daniel Brucker — known also for his part in spreading the opal clock myth — ardently popularized the belief. In reality, as opposed to serving as FDR’s private train, MNCW #002 was rather utilitarian in nature, existing as a “tool car” or “baggage car” to hold blocks, frogs, and other tools needed to clear and re-rail a train car. As a result of being used for storage under Grand Central, the train escaped being scrapped, making it one of the only cars left of its era in Grand Central history. It currently resides at the Danbury Railway Museum where it was relocated in 2019.

Ultimately, the story of FDR’s train car and Track 61 can be easily dissolved by closely examining the structure and materials used throughout the train car and the Waldorf-Astoria. Though the widest door of the baggage car could potentially have fit an armor-plated limousine, it would have been impossible for the limousine to turn and fit within the baggage car itself. While the elevator from Track 61 exists, it opens into the Waldorf-Astoria garage, not directly into the hotel as the myth supposes it does.

In addition, though Bruckner claimed that the glass windows that line the clerestory of the train “were converted gun ports” that could protect the President, the windows were instead simply used for ventilation. In fact, the windows of MNCW #002 can be seen on many train cars made during the same time period, including August Belmont Jr.’s private car. As Karl Zimmerman wrote in Trains Magazine, “[Dan] Brucker is the true believer of the ‘FDR siding’ mystique and the keeper of the flame.”

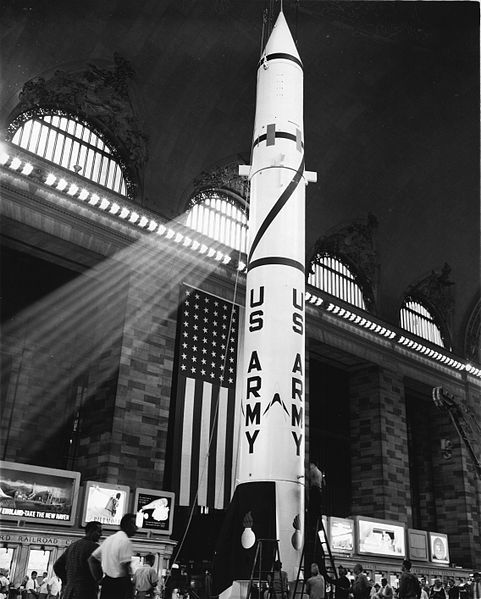

For those who have heard that a 1957 Redstone rocket was tall enough to bore a hole through the concourse ceiling of Grand Central Terminal, you have been lied to. In reality, the rocket was too short to have done so, standing more than 50 feet shorter than the 125-foot tall concourse. In 2015, we set our sights on debunking this myth. Since the rocket’s sister remains in existence, the original rocket’s measurements can be fact-checked. Residing in Warren, New Hampshire, the rocket’s sister stands at only 70 feet, serving as a local monument for a town that only houses around 900 residents.

A Wiki of Astronautics article stated that the original Redstone was exactly 69.32 feet, while the New York Times reported in 1957 that the Grand Central rocket was 63 feet. Regardless of the rocket’s true height, it is clear that the creation of the concourse’s hole, in spite of popular belief, was never the result of the rocket. Though the myth of the Redstone rocket remains false, a hole does exist in Grand Central’s ceiling. According to Jim Henderson, a retired telephone switchman in New York City, the hole was created to anchor a stabilizing wire.

Many today believe that Grand Central Terminal’s sub-basement, known as M42, served as a target of the Nazi regime during World War II. However, while some truth can be found within the stories surrounding M42, the clandestine sub-basement’s legacy remains riddled with lies.

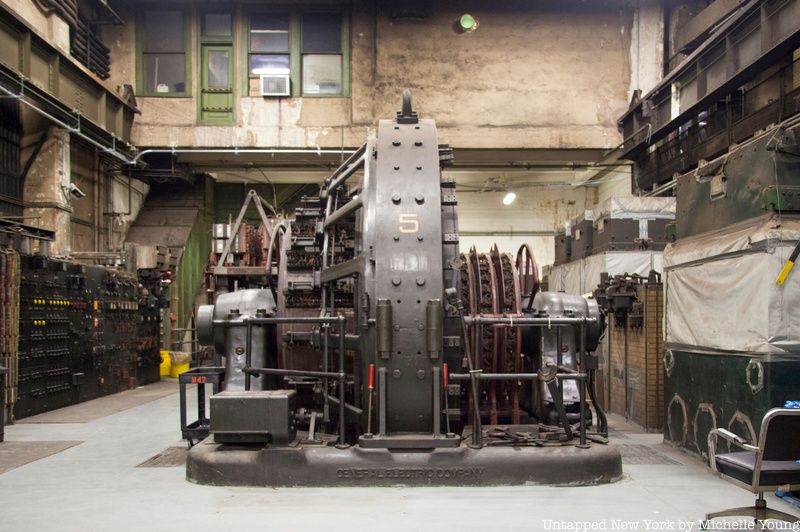

At the base of the myth is the belief that M42’s substations opened when Grand Central did in 1913. This is false. Instead, the terminal’s original electric power conversion substation was located above ground at 50th Street and moved under the Graybar Building in 1929 so that the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel could be built.

Another mythical tale surrounding Grand Central is that of its infiltration by Nazi spies during World War II. Though German spies, also known as saboteurs, were sent to the United States through Operations Pastorius and Magpie, the substations of Grand Central were never any of their targets. While Grand Central might have been a plausible target for Operation Pastorius as it sought to disrupt train movement in the New York region, no official documentation has ever connected the substations to the operation. The website I Ride the Harlem Line did the heavy lifting to debunk this myth.

In relation to Operation Pastorius, it is widely believed that Nazi saboteurs were caught after they attempted to check a bag at Grand Central or had simply been arrested in the terminal. As the story goes, the eight saboteurs were caught because of the actions of George John Dasch, a Nazi who proceeded to call the FBI soon after their arrival in New York City and Florida. Though his teammates thought the call to be a joke, Dasch boarded a train headed for Washington D.C. a few days later to meet with the FBI, revealing that he sought to fight against Hitlerism and had decided to expose the mission as soon as it had been assigned to him. In reality, most of the spies never set foot in Grand Central with the New York team using the Long Island Rail Road and Penn Station to travel. From the Florida U-boat landing team, members Thiel and Kerling actually made their way through Grand Central because they feared direct trains from the state were being monitored. They, therefore, opted to take a roundabout route to New York via Cincinnati. In the end, all of the saboteurs except for Dasch and Burger, who had assisted in corroborating Dasch’s story, were executed by electrocution after a military tribunal within two months of their arrival from Germany.

Another myth surrounds Grand Central Terminal’s clock: the popular phrase “meet me at the clock/under the clock” originated from the clock. According to Mandy Edgecombe, the Grand Central tour guide for Untapped New York and a former National Park Ranger, the first “meet me at the clock” reference was made in regards to the clock at the former Hotel Astor in Times Square. The 1945 Judy Garland and Robert Walker movie, The Clock launched the phrase onto the national stage. After Soldier Joe, played by Walker, meets Garland’s Alice by chance at Penn Station, the two fall in love. During one of the film’s most iconic scenes, Joe asks Alice, “Where will I meet you” to which she responds, “Under the clock at the Astor at seven,” cementing the longstanding tradition of meeting for a date at the hotel’s clock.

Over time, the original Pennsylvania Station’s clock also became associated with the phrase “meet me under the clock.” Later, the song “Meet Me at the Hyphen” popularized the phrase’s connection to the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. Besides these two locations, the Biltmore Hotel and the Roosevelt Hotel have also been mentioned in reference to the phrase. Ultimately, “meet me under the clock” has a long line of associations with New York City landmarks other than Grand Central. At its core, the phrase still remains directly tied to New York City’s romantic scene.

The argument has been made that if the Nazis had managed to take out M42’s substations during World War II, all train movement in the Northeast would cease. In reality, during World War II, M42’s two substations worked alongside eight others to convert power for usage by trains throughout the Northeast. This signifies that had the substations been disabled, disruptions would have ensued — particularly for Grand Central and the nearby buildings and hotels that depended on their power exclusively — but Northeast rail lines as a whole would not have ceased functioning.

It has also been claimed that a bucket of sand dropped onto the substation’s 10 rotary converters could entirely disable the electrical system it powered. When opened in 1930, the converters illuminated more than 100,000 electric lights, helped move 650 trains and 325 elevators daily, and supplied 28 buildings with heat and hot water. The truth is that the sand would have only temporarily damaged the rotaries and any fried parts could have been easily replaced to restore the rotary. Moreover, one bucket of sand would have only taken out one rotary, and as M42 had 10, the ensuing damage would not have been enough to topple its entire electrical system.

The painting of the constellations on the ceiling of the massive, cathedral-like Main Concourse is backward. No one knows for sure how the mix-up occurred, but the Vanderbilt family claimed that it was no accident: the zodiac was intended to be viewed from a divine perspective, rather than a human one, inside his temple to transportation. This contrasted with information published in a pamphlet when the terminal opened that said “it is safe to say that many school children will go to the Grand Central Terminal to study this representation of the heavens.”

After commuters noticed the inversion, creators of the mural, astronomer Dr. Harold Jacoby of Columbia University and painter Charles Basing of the Hewlett-Basing Studio, were asked how the ceiling’s layout could have gotten flipped. Jacoby offered the explanation that the original diagram had been laid out correctly and would match perfectly against a celestial atlas. As such, the diagram was meant to be held overhead. When the image was projected onto the ceiling for painting, Basing (according to Jacoby) must have laid it on the floor and projected it upwards, reversing the image. As for Basing, he “showed little interest in the technical defects and added that he thought the work had been done very well.” The complete truth behind this myth may never be uncovered.

The clock encased by French sculptor Jules-Felix Coutan's colossal "Transportation' statues on the 42nd Street facade has been advertised (including by the official Grand Central Terminal website) as the largest stained glass clock made by the renowned Tiffany glass studio. If Tiffany actually made the clock, this would be true, however, experts cast doubt on the clockface's origins.

When the clock was restored by Rohlf's Stained & Leaded Glass Studio, Inc., no Tiffany signatures were found on any of the sixteen original pieces. Many sources that describe the clock in detail, such as the Terminal’s National Register of Historic Places designation and newspaper articles from the time of the clock's installation (over a year after the terminal's opening), do not specifically call the clock a Tiffany piece. The sculptures are what made headlines at the time. As the New York Times reported, the figures were the largest sculptural group in the world. Further, books by Tiffany from 1913 through 2004 make no mention of the clock among the studio’s other work.

Additional reporting by Nicole Saraniero

Next, check out the Top Secrets of NYC’s Grand Central Terminal!

This post contains affiliate links, which means Untapped New York earns a commission. There is no extra cost to you and the commissions earned help support our mission of independent journalism!

Subscribe to our newsletter