Robert Rauschenberg's New York: When Giants Walked the Earth

Explore Rauschberg's photographs and collages featuring images of NYC!

The Flatiron District in Manhattan is perhaps most famous for containing the Flatiron Building, one of the city’s most recognizable landmarks. Madison Square Park to the north of the district is a popular gathering spot for locals and tourists alike, providing views of the skyscrapers surrounding the green space. Though, the Flatiron District has quite a historic past, from containing two previous Madison Square Gardens to serving as a space for some of New York’s wealthiest and most creative women designers. A destination for cultural icons including George Gershwin, the Flatiron District was home to many art and music sites, as well as some interesting architectural projects. Here are the top 10 secrets of the Flatiron District!

Three levels below the Flatiron Building sit three massive original 1903 coal-fed boilers that are still in place next to a far smaller more modern boiler. These boilers are the remnants of a dream from the early 20th century to make New York’s burgeoning skyscrapers self-sufficient. Though this super basement is not open to the public, Untapped New York was invited below this historic landmark to understand the original source of its power: a coal-powered power plant.

Though it no longer exists, there used to be an elevator that would transport the coal necessary to fuel the boilers down from street level. Today, a shaft remains that provides a view of the sidewalk and sky, stories above the power center. On a basement level just above the boilers sit the remnants of the water system that once supported the hydraulic elevator system. Not as efficient as the boilers, the water system occasionally flooded and often caused the elevator to move slowly — “If you jumped on in the lobby and went to the 20th floor, it could take you ten minutes,” Sonny Atis, the long-time superintendent of the landmarked building, told Untapped New York. Though the Flatiron Building recently installed central air and heating and new elevators, the remnants of its coal-powered past are important to retain in the building’s history.

A sky bridge once connected the Metropolitan Life North Building (11 Madison Avenue) to the MetLife Tower, which was modeled after St. Mark’s Campanile in Venice, Italy. Made of stainless steel and glass windows with a geometric grid-pattern windowpane, the sky bridge is one of many architectural feats commandeered by The Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. In addition to the sky bridge, the company built a number of housing developments, including New York’s Stuyvesant Town and Los Angeles’ Park La Brea Apartments.

However, what goes up must come down eventually. After an Untapped New York Insider noticed construction happening on the sky bridge and asked Untapped New York to get to the bottom of it, we determined the sky bridge was undergoing demolition. Though not the first MetLife sky bridge to get demolished as the company often fancied connecting their buildings with sky bridges, it is one of the last. The demolition of the sky bridge is a result of the construction of One Madison, and the developer SL Green contends that it was necessary due to the setbacks required. To see more photographs of the sky bridge over the years, check out Statz‘s photography.

The Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace National Historic Site is New York City’s only presidential birthplace open to the public. Roosevelt was born here in 1858 and lived there until 1872, though in 1916, the home was demolished to make way for a retail building. In 1919, weeks after his death, the Women’s Roosevelt Memorial Association purchased the lot on which the home had been located to recreate his childhood home. The reconstructed home reenvisions the interior design of the original house from the years 1865 to 1872.

The home, located between Broadway and Park Avenue South, was originally built in 1848. Though Theodate Pope Riddle, who survived the sinking of the Lusitania and designed a number of estates in Connecticut and New York, was tasked with reconstructing the home followng its destruction. The row house next door was instrumental in the redesign, and the home was refurbished with help from Edith Roosevelt. The three-story brownstone was donated to the National Park Service in 1963.

In the early-to-mid 1900s, the Flatiron District was a major center for toy manufacturing and production. centered at 200 Fifth Avenue, also called the Toy Center. Though recently converted into offices, the 16-story Toy Center opened as an office building in 1909. It stood on the site of the former Madison Cottage, which was replaced by Franconi’s Hippodrome, which was replaced by the Fifth Avenue Hotel. A landmark clock still stands outside the bulding telling passengers the time where the hotel stood. The Toy Center was originally called the Fifth Avenue Building and was designed by Robert Maynicke.

During World War I, the building became a center of New York City’s toy industry. This sudden rise was due to restrictions on European imports, meaning most toys could not enter the United States. In addition to toy companies, the building was also occupied from 1910 to 1927 by the Boy Scouts of America National Headquarters. Many major companies moved in during the World War II-era, and the complex expanded when 1107 Broadway was acquired in 1967 and connected to the original building. The building manager even restricted leases in the 1960s to just toy manufacturers. At its peak, 600 tenants accounted for about 95 percent of nationwide toy transactions, amounting to $4 billion. The toy industry eventually expanded out from the Flatiron District, though the building has recently hosted parts of the North American International Toy Fair along with the Javits Center.

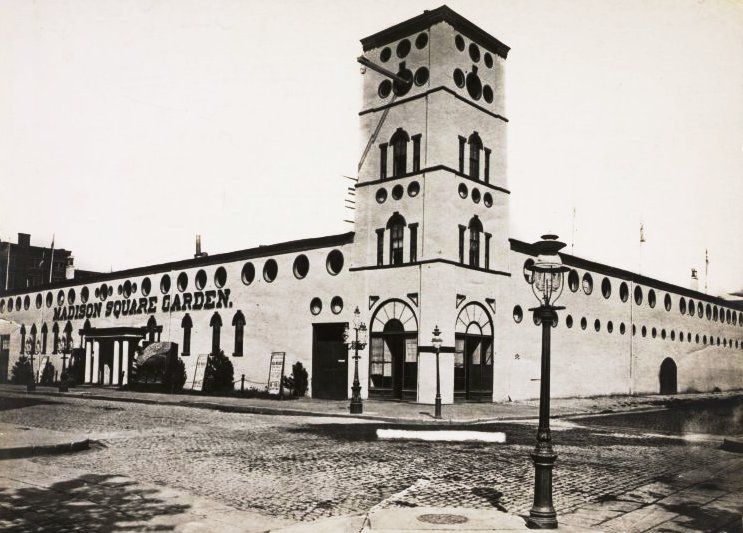

Though Madison Square Garden is located today on Manhattan’s West Side, the “World’s Most Famous Arena” finds its origins near Madison Square. The block northeast of Madison Square Park between 26th and 27th Streets was the site of the first and second Madison Square Gardens. In 1873, P.T. Barnum began hosting his circus, the “Great Roman Hippodrome,” in an obsolete railroad depot north of Madison Square, which was owned by Commodore Vanderbilt. The first arena was officially constructed in 1879, and the circus’ popularity kept the first Madison Square Garden stable, especially considering it struggled financially.

Though, the first Madison Square Garden was demolished in 1889 due to structural issues. A second Madison Square Garden Building was built at the same location and was designed by Stanford White. This meant the show could go on. Workers built it incredibly fast, and in 1890, the building was completed. It was actually the second tallest building in the city until it closed in 1925. Strangely, Stanford White built himself a seduction lair inside the building and was later shot to death on the roof. The third version of Madison Square opened the same year it closed at 49th Street and 8th Avenue.

Though the origins of baseball are debatable, with some claiming the sport began in Cooperstown or Hoboken, some attribute it to Madison Square Park. In 1845, a 25-year-old law clerk named Alexander Cartwright pulled along some friends into the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club. Cartwright drew from elements of older games and then wrote up new rules, many of which still apply to baseball. These rules included a nine-inning game with baseballs that should be pitched, not thrown.

Cartwright and his teammates would practice baseball using these rules in Madison Square Park, specifically at Fifth Avenue and 23rd Street. Then, they moved to the Murray Hill Grounds at 34th Street and Park Avenue. By then, these rules were being picked up by other sports enthusiasts, thus many make the claim that the Flatiron District was the true birthplace of the American pastime.

The Metropolitan Life Insurance Building is a skyscraper occupying a full block in the Flatiron District, currently composed of a North and South building. From 1909 to 1913, the Met Life Tower was the tallest in the world until the Woolworth Building took over. However, few know that the structure could have looked completely different (and would have been much taller). Harvey Wiley Corbett, a San Francisco native, worked as a draftsman with Cass Gilbert. He collaborated with Hugh Ferriss on drawings of what a skyscraper city could look like while abiding by the 1916 Zoning Laws, turning these sketches notable into Art Deco skyscrapers.

Corbett, who had been working for John Rockefeller, set off to create the North Building and reclaim the title of the tallest building in the world. With D. Everett Waid, he took up the project, and the approved design would have created a 100-story tower. The new building would be located in the full block site between East 24th and East 25th Streets and would have drawn heavily from Art Deco elements. Construction began in 1928, though the Great Depression and Black Tuesday led construction to be stopped in 1933. Only 28 stories were built, slightly over a fourth of the goal, and the North Building was eventually completed in 1950.

The Christmas tree lighting at Rockefeller Center pulls people from all over the world to bring in the holiday. Though, Christmas tree displays in the United States actually date back 1912 when the first public Christmas tree lighting ocurred in Madison Square Park using a tree from the Adirondacks with lights from the Edison Company.

As part of a progressive movement to help the poor, according to The Bowery Boys, Emilie Herreshoff planned the lighting to emulate European civic customs as a “clean, proper, somber affair,” counter-programming to the Times Square celebration. Jacob Riis, the photographer behind How the Other Half Lives, believed that the holidays did not call for great and raucous celebrations, so events like Christmas tree lightings would give the poor an alternative. The Star of Hope monument in the park corresponds today to the approximate point of the first tree lighting.

The Ladies’ Mile Historic District was a shopping district extending roughly from 15th Street to 24th Street between Park Avenue South and Sixth Avenue. A popular site at the end of the 19th century, the shopping district replaced previously identical brownstone townhouses. Many of the department stores incorporated cast iron into the Beaux-Arts, Romanesque Revival, and Neo-Renaissance designs. Another popular location within the district was The Fifth Avenue Hotel, whose guests included the Prince of Wales. The New York Landmarks Preservation Committee designated the area was designated a histroric district in 1989 to preserve 440 buildings.

During the district’s peak, many of New York’s first department stores settled there, including B. Altman, Bergdorf Goodman, Lord & Taylor, Tiffany & Co. The Sohmer Piano Building contained showrooms and manufacturing facilities, while Steinway Hall and the Academy of Music invited some of the largest names in music at the time. The original Metropolitan Museum of Art did the same for many famous artists and art lovers. Women were the target consumers of many of the stores, and the neighborhood became a safe place for women to walk without men. By the time the Flatiron Building was completed in the early 1900s, the neighborhood was bustling, though World War I resulted in many of the buildings becoming warehouses. Most were not torn down though, and in the place of the original department stores are plenty of newer clothing retailers.

On the border of the Flatiron District and Rose Hill is the 69th Regiment Armory, a historic National Guard building on Lexington Avenue completed in 1906 in the Beaux-Arts style. On February 17, 1913, the Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, opened to the public. Organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), it was one of the first exhibitions dedicated to modern art in the United States. The most famous Fauvists and Cubists at the time presented work at the exhibition.

Walt Kuhn, one of the founding members of AAPS, went on a collecting tour across the Netherlands, France, England, and Germany in search of the best modern art. Kuhn secured three notable paintings which would go on to define the exhibition: Duchamp‘s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Matisse‘s Blue Nude, and his Madras Rouge. The Armory Show brought together over 1,300 artworks representing over 300 artists of the Fauvist, Cubist, and Impressionist movements. The exhibition featured 18 exhibitions labeled by letters, with a significant concentration of American and French works. About a fifth of the artists were women, but most have entered into relative obscurity. Critics included none other than former Flatiron District resident President Theodore Roosevelt, who exclaimed, “That’s not art!” after seeing some of the artworks represented.

The first basement level of the Flatiron Building was once the Tavern Louis, which was in operation when the building opened and later became a speakeasy. Irving Berlin visited there once and brought a famous jazz band from the Cotton Club in Harlem to perform. The basement levels extend beyond the footprint of the building and go under the road itself, meaning there was plenty of space for people to mingle and dine.

Old photographs reveal a bustling space with glass mirrored columns and marble walls. The same pillars are located in the same place today, along with marble wall slabs next to the elevator and at the staircase. The restaurant and bar could be accessed directly from a staircase on the street, and there is still a brick outline of where the staircase ended. In the cleaning closet are some remnants of the men’s bathroom with marble stalls and wooden water tanks.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Flatiron Building!

Subscribe to our newsletter