♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

Seven years before construction of the Holland Tunnel commenced in 1920, the New York State Bridge and Tunnel Commission and the New Jersey Interstate Bridge and Tunnel Commission decided that constructing a tunnel was their only option to connect New Jersey to New York City. Building a bridge would not be possible feasible because New York’s elevation did not meet the 200-foot bridge height clearance for ships to use it. Using a twin-tube design created by Clifford Holland, the dual coalition named him the chief engineer of the tunnel. From here, he became the tunnel’s namesake. Today, commuters and weekend travelers are perhaps all too familiar with the Holland Tunnel. Yet they may not know its secrets. Here are the top 10 secrets of the Holland Tunnel!

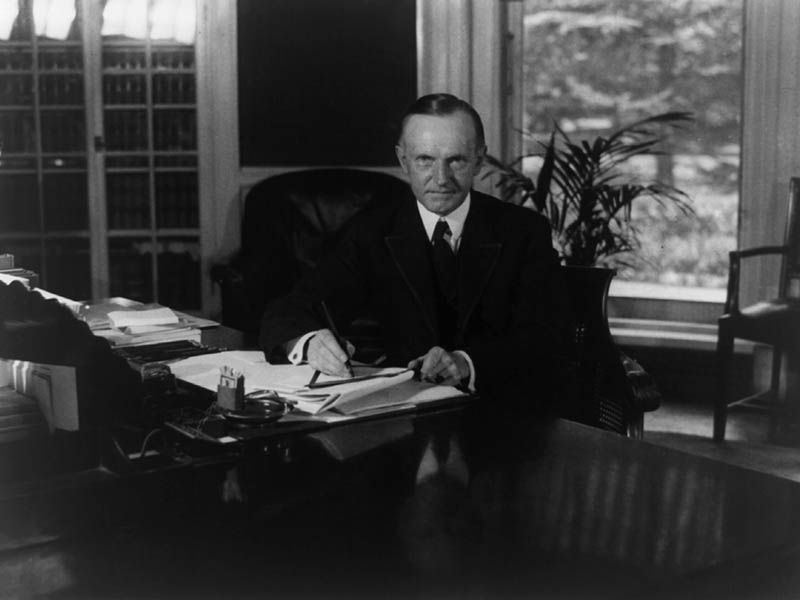

From his Mayflower yacht in the Potomac River, President Calvin Coolidge opened the Holland Tunnel from a distance at 4:55 pm on November 13, 1927. He turned a gold telegraph key typically used to send Morse code, which separated two American flags at the entrance of the Holland Tunnel.

United States Presidents were often remotely involved in the opening ceremonies of important construction during this era. In 1931, President Herbert Hoover “turned on” the lights to the Empire State Building from his desk in Washington D.C. President Woodrow Wilson also used the same key used by President Calvin Coolidge to detonate the last blast in the construction of the Panama Canal as well.

A narrow, one-person, two-foot wide electric car debuted in the Holland Tunnel in 1955. Called the catwalk car, this vehicle was used as a tool for police to patrol the entire length of the tunnel. The car featured a swivel seat so that the police could move back and forth without having to leave their seat. Although the car only moved at 6 or 12 miles per hour, it still moved quickly during rush hour. As The New York Times writes “the catwalk car was the fastest, surest way through the tunnel, gliding blithely past the most epic traffic jams — equipped with no horn, because none was needed.”

As other tunnels sprung up in New York City, the catwalk car technology spread across the city. The Lincoln Tunnel, which was the first mechanically ventilated underwater automobile tunnel to be built under the Hudson River, also featured these cars. Though according to The New York Times, the catwalk car was only operational until the spring of 2011. By then, the car had undergone many remodels.

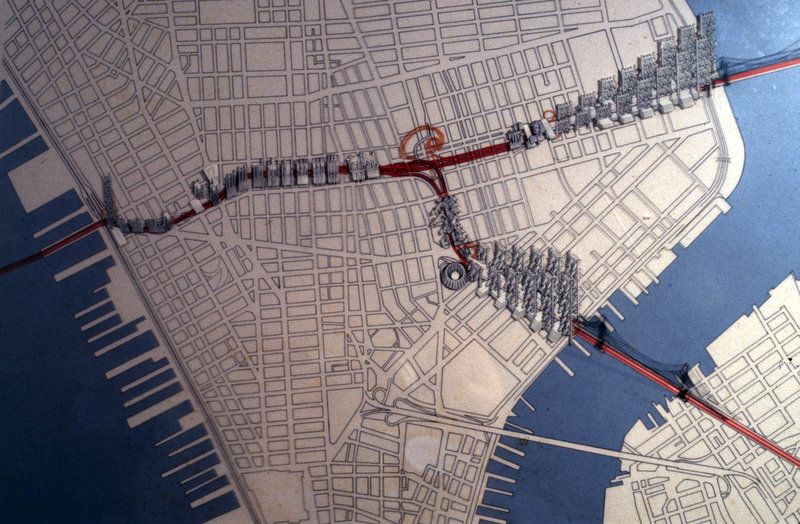

Robert Moses touched just about every inch of infrastructure in New York City during the mid-20th century, including the Harlem Tunnel. One of his most controversial plots was the plan for the Lower Manhattan Expressway or, LOMEX. The plan would connect the Manhattan Bridge and the Williamsburg Bridge to the Holland Tunnel via SoHo and Little Italy.

The plan, as pictured above would merge traffic via a highway over Soho that would continue into the Holland Tunnel to get to Jersey. This plan was defeated by widespread community action against it led most prominently by his nemesis, Jane Jacobs. The $72 million dollar project would have razed fourteen blocks of SoHo and displaced approximately 2,000 households and 800 local businesses.

Even though it was illegal to transport some hazardous material through the tunnel. a truck loaded with carbon disulfide drove into the Holland Tunnel in 1949. Carbon disulfide is a colorless liquid that can cause dizziness, poor sleep, headache, anxiety, anorexia, weight loss, and vision changes — it is also highly flammable. One of its eighty 55-gallon drums fell off and broke open, emitting vapors that caught fire when coming in contact with the ground.

The fire caused 66 injuries, two deaths, and approximately $600,000 worth of damage to the south tube of the tunnel. The Port Authority then adopted strict rules to prevent such an accident from occurring again. Needless to say, throughout the 1949 fire, the tunnel’s famous ventilation system was at full capacity.

The New Jersey Interstate Bridge and Tunnel Commission and the New York State Bridge and Tunnel Commission started brainstorming methods to connect the bodies of land in 1906. By 1920, they began work on the tunnel. During its development, the Holland Tunnel was quite practically referred to as the Hudson River Vehicular Tunnel or the Canal Street Tunnel.

Many proposed architectural models for the tunnel but the developers chose a design by Clifford Millburn Holland, an American civil engineer. His plan featured two tunnels, each with two lanes. Tragically, the day before the two halves of the tunnel were supposed to link on October 28, 1924, Holland died of a heart attack. The New York Times linked his death to stress from the tunnel’s construction. The events of the day, which were to include a remote detonation by President Coolidge, were canceled in his honor, and then the tunnel was named after him less than a month later.

When the Holland Tunnel was being built, automobile exhaust contained carbon monoxide levels that could become poisonous within a tunnel. As such, the tunnel would become the first tunnel in the world to be equipped with a ventilation system, “designed specifically for automobile and truck exhaust fumes,” according to ASCE Metropolitan.

There are a total of four ventilation buildings, which contain 84 fans that push air through the tunnel. There are also 42 blowers and 42 exhausters. When the tunnel opened, the plan was to change the air 42 times an hour, which is about once every 85 seconds, but in practice now, not all the fans operate at the same time. Tunnel ventilation buildings now dot the New York City waterfront edge, becoming some of New York’s mysterious windowless buildings.

Shortly before the Holland Tunnel opened, The New York Times reported that “pedestrians will be allowed to use the tunnels at a toll described as ‘not encouraging.'” That did not stop an estimated 20,000 people from walking the entire length of the tunnel on the day it opened. At 12;01 a.m. the next day, the tunnel opened to vehicular traffic.

Today, more than 100,000 vehicles pass through the tunnel daily. Though the Holland Tunnel toll charges a minimum of $10.75 — this price is for motorcyclists — people stream through the tunnel all day. Similar to the pedestrians on opening day, contemporary Tristate Area residents will pay whatever they need to travel between New York City and New Jersey.

The Holland Tunnel was not only the first underwater vehicular tunnel in the Hudson River, but it was also the longest in the world when it opened. According to the ASCE Metropolitan section, it also had the largest tube width in the world, at 29.5 feet, setting the standard for other vehicular tunnels throughout the world that followed.

Since the Holland Tunnel was completed in 1927, New York City has welcomed a handful of new tunnels, including the Lincoln Tunnel and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. At 9,117 feet long, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel now holds the title for the longest underwater vehicular tunnel in New York City. When the Rogfast Tunnel in Norway is completed, it will be the longest and deepest underwater vehicular tunnel in the world at 17 miles long.

New York and New Jersey jointly commissioned the land connection that would become the Holland Tunnel in 1906. However, this Hudson River crossing was originally conceptualized as a bridge. ASCE Metropolitan reports, “a bridge was not economically feasible due to the long span that would be required to cross the Hudson River, the deep foundations that would be needed to reach bedrock, and the lengthy approaches would necessitate the purchase of large amounts of real estate.”

Luckily, other bridges have been built to connect New York City and New Jersey. The George Washington Bridge, which was completed in 1931, serves as a connection between the two states in uptown Manhattan. Daily traffic, however, is lower on the George Washington bridge as only about 250,000 to 300,000 cars pass over the bridge each day.

During the construction of the Holland Tunnel, St. John’s Park Freight Depot, the southern terminus of the Hudson River Railway Company, was demolished. In its place, bounded by Hudson, Laight, Beach, and Varick streets, stood a rotary and the exits from the tunnel.

Before the Hudson River Railway Company build the freight depot, though, the area of land on which they would work had a storied history. Once part of a plantation, the land later became the property of the English crown. The crown deeded the space to Trinity Church, which in turn built St. John’s Chapel. Trinity Church also developed St. John’s Park, the first park in New York City to become surrounded by townhouses. The neighborhood was known as St. John’s Park until the Hudson River Railway Company bought it to build the freight depot. Today, the rotary space is still known as St. John’s Park, but it is not actually part of the park system and is inaccessible to the public.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of the Lincoln Tunnel and 5 things we can blame on Robert Moses.

Subscribe to our newsletter