♀️ The Trailblazing Women of Wall Street

Women have long shaped Wall Street—even when history tried to write them out.

Grand Central Terminal is one of the most visited sites in New York City, with around 750,000 people passing through its storied passages each day. Though, many places within the over 100-year-old building remain hidden and unnoticed by the masses. From long-forgotten tunnels that once led to luxury hotels, to off-limits basements that do not even appear on blueprints, here are ten hidden places inside the iconic Grand Central Terminal.

From hidden tennis courts to the remnants of a lost movie theater and an office-turned-speakeasy, uncover the secrets of New York City's iconic train terminal!

To see some of these hidden sites in person, join Untapped New York for a tour of Grand Central. On this unique walking tour, you will discover the history of the Beaux Arts train station, from its glittering glory days to disrepair and modern quests to save it. Our top-rated tour guides will make you experience what most miss: its hidden features, design quirks, and more. Read on to learn the secret details related to the terminal’s hidden spaces.

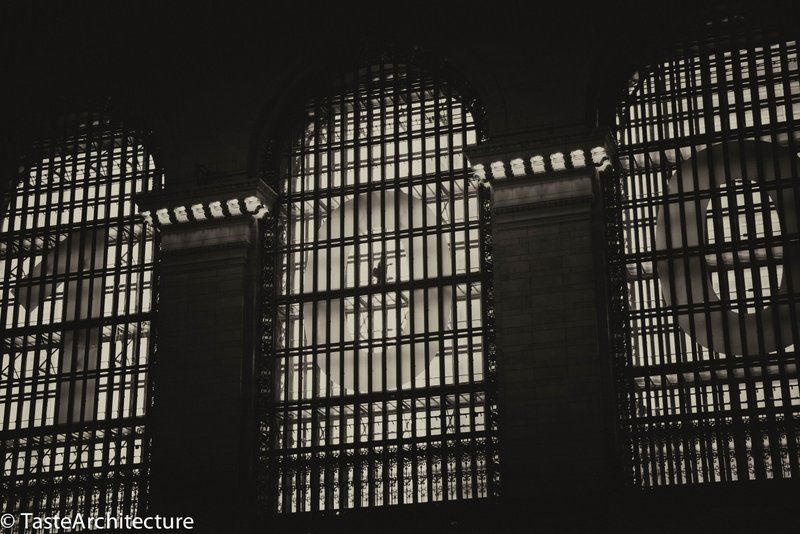

While most people will recognize the signature glass windows of Grand Central Terminal‘s atrium, many may be surprised to know that those windows contain walkways. If you look closely at the above photo, you will see someone crossing between the first zero in 100.

The catwalks that run across the massive windows connect offices so employees do not have to fight through the crowds within the station to get where they need to go. A special key and a bit of nerve are required to gain access and traverse the elevated glass pathways. You can see photos from Untapped Cities’ visit inside here!

The terminal’s hidden tennis courts, run by the Vanderbilt Tennis Club, are open to the public but few people even know they are there. The space where the full-sized hard court and two practice courts of the tennis club are now located, called The Annex, once served as an art gallery and then as a television studio for CBS. In the 1960s, Hungarian immigrant Geza A. Gazdag founded the Vanderbilt Athletic Club in the terminal and constructed a 65-foot-long indoor ski slope made of astroturf and two clay tennis courts in the Annex. In the 1980s, the club was taken over by Donald Trump and catered to the rich and famous as a private court until the early 2000s. At that time, a new fourth floor was built and new courts became more accessible to the general public.

The easiest way to access the facility is to head to the Campbell Apartment, where you will find elevators in the lobby outside the bar that will bring you directly there. Alternatively, you can also take the elevators located halfway down the ramp that leads to the Oyster Bar and Tracks 100-117. There is even a street entrance on Vanderbilt Avenue (between Madison and Park Aves.) between 42nd and 43rd streets.

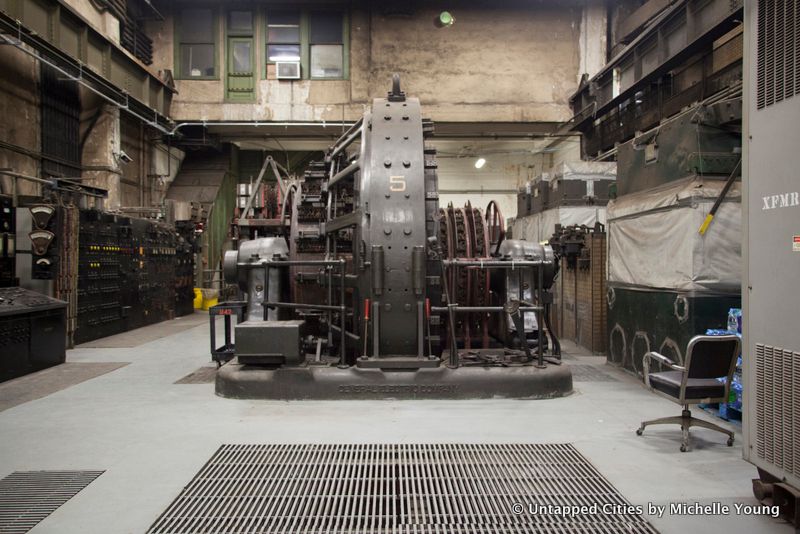

Ten stories below Grand Central Terminal’s main atrium there lies a space that is so secretive it doesn’t appear on any maps or blueprints of the terminal. The location’s mere existence was only recognized as recently as the late 1980s. If an unauthorized person made his way down to the M42 basement, he risked being shot. What was so important inside this subterranean room? Nine rotary converters that provided power for all of the trains that ran through Grand Central.

The converters, which weigh 15 tons each, are no longer in use, but one remains in place as a tribute to its former service. Especially during World War II, it was imperative that the railroads ran without a hitch, as trains were used to transport troops and weapons to the ports of the east coast. A handful of Grand Central myths center around the basement: it was target for the Nazis during World War II and it could provide power for all trains in the Northeast, However, we debunked these myths for you.

Metro-North workers inside the information kiosk sit beneath the iconic opaline glass-faced clock in the center of the main atrium. As they oversee thousands of individuals passing through the terminal, they guard one of the terminal’s oldest secrets, a hidden staircase that connects the upper and lower levels.

The brass spiral staircase is accessed through the sliding doors of the brass structure at the center of the kiosk. This staircase allows workers to quickly access the upper and lower levels of the station. Before 9/11, the staircase rising from the lower level was actually the only way to access the main level kiosk. Now there is now a door at the main level which allows for quick and safe exits and entries.

Measuring in at 13 feet in diameter, the clock that crowns the exterior facade of Grand Central Terminal was thought to be the largest Tiffany clock in the world. Access to the clock for maintenance and cleaning is obtained by going up a very narrow staircase that leads to a small space behind the clock face. In order to clean the front face of the clock, the pane of glass with the numeral six opens up like a window. This also provides a unique view of Park Avenue for those select few who get to look out of it.

The Tiffany Clock restoration took 12 years in part because the staircase that leads to the clock is so narrow that each piece had to be removed individually, according to the restorers at Rohlf’s Stained and Leaded Glass. There was also extensive damage since its installation in 1914, so the process that began in 1992 involved both repair and replication, in the case of missing parts. Then everything had to be reinstalled piece by piece.

In the 1930s, Grand Central used to be home to the Grand Central Theatre, a 242-seat theater that ran newsreels, shorts, and cartoons. The little theater, designed by Tony Sarg (the artist who created the first balloons for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade), was billed as the “most intimate theatre in America” according to the website I Ride the Harlem Line. Sarg tailored the movie-going experience to the commuter with an illuminated clock next to the screen for those worried about missing their train. Organizers even considered having the clock run 30 seconds fast. In vintage advertisements on Gothamist, the theater advertised their seats with “Neck-to-knee Comfort for N.Y. Commuters.”

The theater was in operation for nearly three decades before it was turned into a retail space. Today, you can still see remnants of it inside the Grande Harvest Wine shop next to Track 17. If you look up, you will find a mural from the theater that depicts the solar system and shooting stars.

Sometimes the most surprising finds are in the most unassuming places, like a parking garage. On a visit to Grand Central Terminal, Untapped Cities tour guide Justin Rivers noticed the famed arched herringbone pattern typical of Guastavino tile work, just like the famous ceiling of the Grand Central Oyster Bar. Research into this area revealed that it was once part of the Biltmore Hotel, a grand Whitney Warren and Charles Wetmore-designed structure that was built as part of “Terminal City,” a compound of hotels and other buildings connected to Grand Central Terminal that was proposed in the original plans by Charles A. Reed and Allen H. Stem, along with William Wilgus.

One of the hotel’s best amenities was the ease with which guests could come and go using the hotel’s connection to Grand Central Terminal. Guests of the Biltmore arriving at Grand Central Terminal would have their luggage collected from the train by porters and then they would travel via tunnel to an elevator in the hotel’s basement and be carried up into the hotel without ever having to step outside. The pathway leading into the tunnel from Grand Central Terminal is not marked — it is located on the western end of the Terminal, next to the Pylones store and the Transit Museum annex.

Nestled in the corner of Grand Central Terminal is a hidden bar in the former private office and entertainment space of business tycoon John W. Campbell. The Campbell Apartment still maintains original pieces of its Gilded Age past such as Campbell’s safe, a large stone fireplace, and wooden cabinets that now hold beer instead of business papers.

Though it may not be easy to spot, it is open to the public and anyone passing through the terminal can stop in for a drink, meal, or snack. The bar serves a wide range of beverages including specially crafted cocktails as well as a lunch menu and small plates. Notable menu items include the Grand Central Spritz, which is made of grey goose vodka, st. germain, ruffino prosecco, lime juice, club soda.

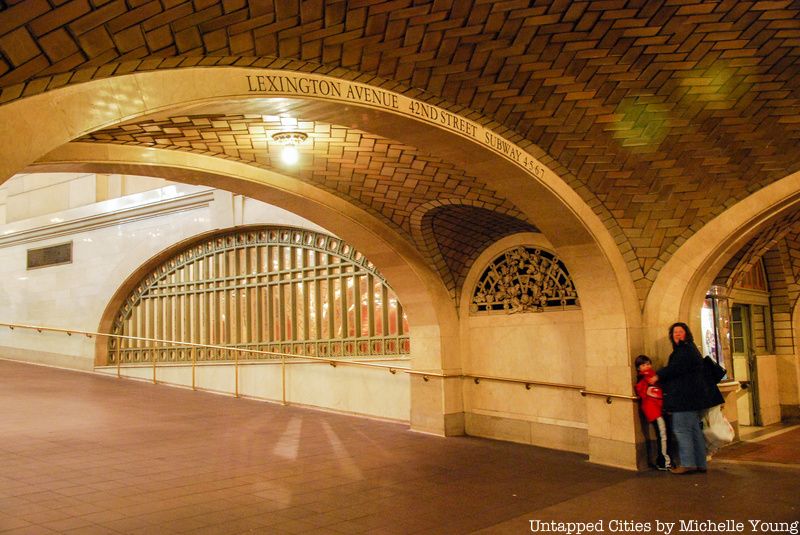

Probably the most well-known hidden place inside Grand Central is the whispering gallery. Located between the Main Concourse and Vanderbilt Hall, the entertaining acoustic quirk of this 2,000-square-foot chamber is not apparently obvious.

The design of the vaulted chamber creates a “telegraphing” effect which allows two people standing at opposite corners of the gallery to speak to each other as if they are standing right next to each other. It is not known if the gallery was intended to have this special feature, or if the acoustics were an accidental architectural perk. It is one of several “whispering” galleries and benches in the city.

To see these hidden places in person, join us on the tour of the secrets of Grand Central!

Subscribe to our newsletter