After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

LaGuardia Airport in Queens, named after New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, is one of the busiest in the country as a top hub for Delta Air Lines and American Airlines. By the early 2000s, the airport’s reputation was perhaps at its lowest due to dirty facilities and inferior customer service metrics. In recent years, both Terminals B and C opened to the public after major renovations, while Terminal A retained its decades-old architectural features from its time as the Marine Air Terminal. The new terminals helped LaGuardia’s reputation improve dramatically. In March 2023, LaGuardia’s Terminal B was named the World’s Best New Airport Terminal and the terminal received the first five-star rating for an airport terminal in North America from Skytrax, the leading authority in airport experience.

About a dozen new art projects were commissioned and installed at the new terminals as part of these renovations. This makes LaGuardia Airport an art museum in itself, housing works from a 1940 mural to (soon) a 1960s sculpture that hung at Lincoln Center to contemporary installations by local artists. Here is an art guide to LaGuardia Airport, divided into three parts for Terminals A, B, and C.

The Marine Air Terminal was designed in the Art Deco style by William Delano, who worked primarily in the Beaux-Arts tradition and designed Oheka Castle on Long Island. The main terminal consists of a circular core with a three-story entry pavilion that includes a canopy and a large set of doors. The brick facade was originally painted buff, a light brownish yellow with black details, though, by the 1980s, it had been repainted beige. The building was designed with elements of wedding-cake style, which has distinct tiers and setbacks. The building also houses two observation decks and two wings, where passengers would board and exit seaplanes.

The rotunda has light-gray marble floors and wooden benches with arms depicting propeller blades. The lower portion of the rotunda wall is a dark green marble below the signature Flight mural. The wall is divided into 14 bays for stores and ticketing offices, and the second floor is used to house staff offices for meteorologists and radio technicians. Though perhaps the defining feature of the entire structure is the frieze on the exterior of the building that depicts flying fish. The yellow flying fish are accented by a background of light and dark blue waves in direct reference to flying boats. The frieze contains about 2,200 individual tiles.

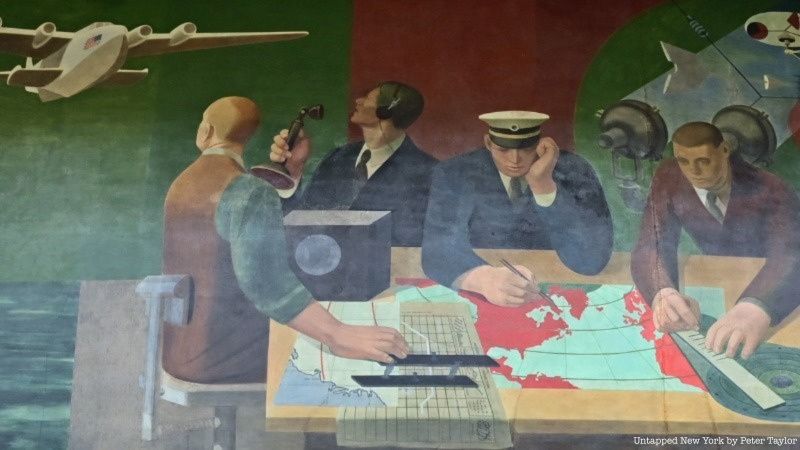

The Works Progress Administration commissioned American artist James Brooks to produce a mural on the history of flight for LaGuardia Airport. The mural became the largest of the entire program. In preparation for the Marine Air Terminal’s 1940 opening, Brooks depicted the invention of flight, including mythological predecessors, of flying as well as the obsession at the time with flying boats. Part of the mural depicts a Boeing B-314 departing, with many waving their goodbyes. In the 1950s, it was misinterpreted as Communist propaganda and was painted over, though it was later restored about three decades later.

Geoffrey Arend, an aviation historian and LaGuardia employee, led efforts to save the mural and bring Brooks back to restore it. The mural was fully restored in 1980, the same year that the terminal was given landmark status. The restoration included all the original references to figures like Icarus and Daedalus, Leonardo DaVinci, and the Wright brothers. There are also depictions of flight as an important privilege for the common man, not just societal elites and the military, which may have been the reason for the mural’s cover-up.

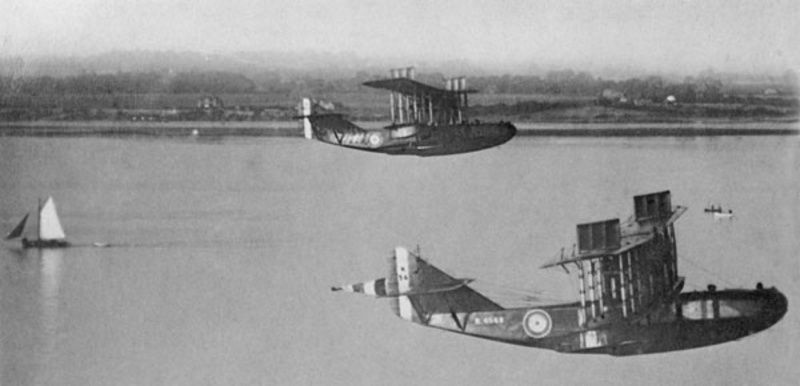

At the center of the Marine Air Terminal is a model of a Boeing B-314, which was installed in October 2021 alongside three new plaques. This model, a 1/10 scale model of the aircraft, replaces an older B-314 loaned to the Pan Am Museum Foundation at the Cradle of Aviation Museum. The new “Yankee Clipper” model was first launched for trans-oceanic travel in the 1930s and was considered a flying boat. Also called floatplanes, flying boats were aircraft that could only land on water. Instead of using pontoons like modern seaplanes, the flying boat had a purpose-built fuselage that gave it the buoyancy to land thousands of pounds of steel in the ocean. Built by Boeing in 1938, the Yankee Clipper was a double-decker aircraft with 36 rooms, an onboard lounge, and a dining hall where passengers would be served five-and-six course meals prepared by chefs from four-star hotels. Men and women had separate dressing rooms and were waited on by white-coat stewards.

The B-314 could cross the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans in one trip and had a cruising speed of 188 miles per hour; some flights lasted longer than 20 hours. The Marine Air Terminal was an important hub for flying boats, though marine airports were popping up all over the country during the 1930s. By the start of World War II, the B-314 was used by fleets of the Army Air Corp and the Navy. Pan American flew missions with the B-314 during the war, such as transporting FDR to the 1943 Casablanca Conference to meet with Winston Churchill. Though by the war’s end, paved airstrips were commonplace, and modern jet airplanes could complete a flying boat’s route in half the time, thus flying boats quickly became artifacts of the past.

The central rotunda of the Marine Air Terminal preserves a bust of the airport’s namesake that was unveiled in 1964. The marble sculpture was installed on the 25th anniversary of the first scheduled flights at the airport. In attendance at the unveiling were Mayor Robert Wagner, Robert Moses, and others who worked closely with La Guardia to help his vision come to fruition. On December 2, 1939, La Guardia greeted the first flight into the airport at 12:01 a.m., which propelled the airport to oversee more than three million flights in the first 25 years alone.

Though Mayor La Guardia passed away in 1947, his wife Marie was also present at the unveiling. The sculpture stands eight feet tall and was created by Luis A. Sanguino. The bust focuses mainly on La Guardia’s head, with his right hand protruding from the marble block. The Barcelona-born sculptor also created a bronze sculpture now in Battery Park called The Immigrants that showcases the diversity of New York City.

Opened to the public in June 2020, Terminal B was one of the largest infrastructure projects in the history of the airport. As part of the development, LaGuardia Gateway Partners in partnership with Public Art Fund commissioned four artworks for the Arrivals and Departures Hall. The permanent site-specific works each have a “lightness of being” that interacts with the natural light and fluid space of the terminal, each work adapting to the space’s architecture. These four works join (at least) two others in Terminal B inviting travelers to feel like a part of the city’s skyscrapers and culture.

Danish artist Jeppe Hein created an installation called All Your Wishes that includes 70 mirror balloons made of stainless steel. The balloons, which are many different colors, appear to be released into the air and float to the ceiling. The balloons are located near shops, restaurants, and passageways. Also included in the installation is a set of three powder-coated aluminum benches painted red that “curve, loop, and twist to form an irresistible invitation to spontaneous expression and social connection,” according to LaGuardia’s website. Hein called these “Modified Social Benches.”

Hein specializes in interactive sculptures drawing from elements of minimalism and conceptual art. After spending time at Alexander Calder’s French studio, he created a set of Modified Social Benches at a park in Cadiz, Spain. Hein has had solo exhibitions at MoMA PS1 and Long Island City‘s Sculpture Center.

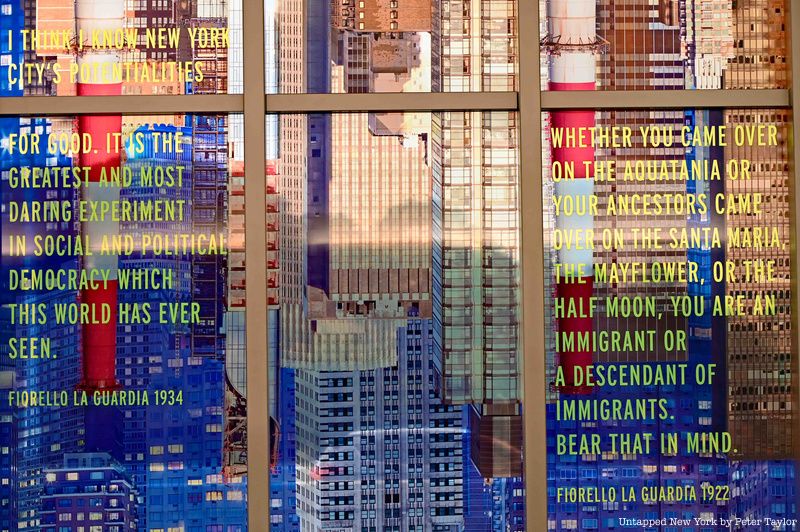

Berlin-based artist Sabine Hornig created a transparent photo collage for LaGuardia called La Guardia Vistas. The photo collage was created with latex ink and vinyl mounted on glass, located along the terminal’s Corridor. The glass façade allows sunlight to create a kaleidoscope of images and text, featuring 1,100 photographs of New York City sites. The artwork measures 42 feet high and 268 feet wide, and photographs were taken by Hornig specifically in Manhattan and Queens. Images include the Manhattan skyline taken from Queens projected like a shadow on the glass, and a second of a nighttime urban cityscape intersecting with a golden skyline. Hornig’s work alludes to LaGuardia’s view of New York as “the entire microcosm of the world,” showcasing tall skyscrapers right next to small houses.

In a reference to Mayor LaGuardia, Hornig included 20 quotes from or about him, including one that states “Would you say these ideas are radical?” Another of his quotes amid skyscrapers says, “We have established the lesson for the entire world. We have demonstrated that it is possible for people coming from all lands and climes of the world… to live together as good neighbors, in peace and harmony. If we can do it here, it can be done elsewhere.”

Artist Laura Owens‘s I 🍕 NY is a two-level tiled mosaic mural on the airport’s largest interior wall. The mural depicts clouds amid a melange of New York City sites, such as (the tip of) the Chrysler Building, halal carts, and “I love New York” shirts. Seagulls fly above a sign for Grand Central-42nd Street, while a nearby portion of the wall reveals the winding Coney Island Cyclone and the Wonder Wheel poking out behind a cloud. The work includes symbols of New York’s transit network, as well as some historical and artistic nods, such as the zodiac signs from the roof of Grand Central Terminal.

According to LaGuardia’s website, “The mosaic’s dynamic composition changes with the viewer’s point of view, as images recognizable from afar become gridded abstractions when seen up close, dissolving into impressionistic colors and out-of-focus glimpses of our imagined city.” Owens, who lives and works in Los Angeles, has recently had solo exhibitions at The Cleveland Museum of Art and the Fondation Vincent van Gogh in Arles, in addition to a 2017 exhibition at The Whitney Museum. She is best known for her large-scale paintings that draw from history.

Sarah Sze‘s sculpture Shorter than the Day was designed to evoke the passage of time through photographs suspended from a web of aluminum and steel. Hundreds of images of different sizes depict the evolution of New York City’s skyline from dawn to midnight, featuring many of sunset and others with the sun radiating against the dark blue sky. The images were also printed on aluminum, appearing like torn paper hanging onto the sculpture via clips. Her sculpture comments on permanence and transience, and it is located near Laura Owens’s mural. The spherical matrix measures 50 feet tall and 26 feet in diameter and overhangs the terminal’s baggage claim.

Sze took inspiration from Emily Dickinson’s poem “Because I Could Not Stop For Death,” specifically the lines “We passed the Setting Sun / Or rather — He passed us.” The poem’s title comes from stanza six of the poem, in which she writes “Since then—’tis Centuries—and yet / Feels shorter than the Day.” Sze also cited the Grand Central Terminal clock as additional inspiration. Sze, a professor of visual arts at Columbia University, often uses everyday materials to explore how technology and information impact daily life. Her works have appeared on the High Line, at the 96th Street subway station, and in solo exhibitions at The Whitney and the Bronx Museum of the Arts.

Located on Level 4 of the Arrivals and Departures Hall, the Terminal B Water Feature consists of two 25-foot-tall circular rings of falling water. Water flows out of more than 450 valves, each of which is individually controlled to shape water into specific shapes or texts. These techniques are coupled with music, videos, and choreographed lighting for water shows. The water feature has three laser projectors and two media servers, with signature shows appearing every 15 minutes between 7 a.m. and 10 p.m. The signature shows include Iconic NY, set to the tune of “New York, New York,” and Arts & Entertainment showcasing the city’s museums, parks, and sports teams.

The water feature’s rings each measure two meters tall and three meters in diameter. The water lands into an upper infinity pool, which empties into a lower pool with four illuminated jumping jets. Built by the French company Aquatique Show, the water feature includes 4,000 gallons of water and cost about $1 million to build.

Though not a reality yet, Richard Lippold’s Orpheus and Apollo will soon be fully installed in Terminal B at LaGuardia’s Central Hall, a glass-enclosed connector between the terminal and the AirTrain. The 40-foot-tall sculpture contains 190 bars of metal and about 450 steel wires, weighing a whopping five tons. It was originally installed in 1962 at Lincoln Center, though it was controversially removed in 2014. Architecture critic Paul Goldberger advocated for the sculpture’s new home in Terminal B after a few years of the sculpture’s absence from the public eye; it did not make a return to the newly renovated David Geffen Hall, as it did not fit in the space.

Lippold, who passed away in 2002, was known for his wire sculptures and his teaching at Hunter College and CUNY schools. He is perhaps best known for his Ad Astra, an abstract sculpture at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. Some of his other works that were located in New York City included Flight at the PanAm Building, Variation Number 7: Full Moon at the Museum of Modern Art, and Untitled, The Four Seasons, and Seagram Building Construction No. 1.

The Bowery Bay Shops at the Terminal B Headhouse is a partnership with Marshall Retail Group featuring 24 retail concepts that reflect aspects of New York City’s history and culture. The shops feature brands such as the Strand Bookstore, Magnolia Bakery, Kate Spade New York, and Brooklyn Roasting Company. In collaboration with Patten Studio, three digital art experiences were constructed in 2021 to make travelers part of New York’s cityscapes.

Using an interactive LED media wall, the interactive murals allow guests to create selfies in the style of 5Pointz graffiti artists including Meres One, Djalouz & Doudoustyleart, Monsieur Plume, Jimmy C, and Dustin Spagnola. One of the screens consists of 215 LED strips that capture the movement of travelers through a complex camera network. The strips then convert the data into silhouettes that appear as part of larger New York City scenes. At the Strand, shoppers can interact with comic vignettes and books on the shelves, pulling shoppers into Central Park, Harlem, and the Fashion District, among others.

Delta Air Lines’ Terminal C opened to the public in June 2022, and alongside new architecture and shops are six new art installations. Delta Air Lines in partnership with the Queens Museum commissioned the permanent installations by artists living and working in New York City. The works, selected from a much larger pool chosen by the museum, are all rooted in New York City’s diversity and culture, from works reusing New York City skylights to works reimagining the immigrant experience.

Skylight Gems by Virginia Overton consists of a dozen glowing gem shapes that were crafted from New York City skylights. The lights are suspended through the terminal’s three-story atrium within the departures and arrivals hall. The Brooklyn-based artist searched salvage shops and occasionally garbage piles to uncover panes of security glass, then replicated the mirror part of the panes to create gem-like pieces. Some of the shapes measure over nine feet, and each has a slightly different color and pattern.

Created to emulate the skylights that many tourists will see after leaving the airport, Skylight Gems is partially inspired by Overton’s father, who would take frequent business trips to New York City and flew right over the city’s tallest buildings. Many of Overton’s artworks use recycled materials as readymade or found objects. In 2018, she became the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at Socrates Sculpture Park in Long Island City, in which she used steel, wood, and other construction materials to comment on issues of land and labor.

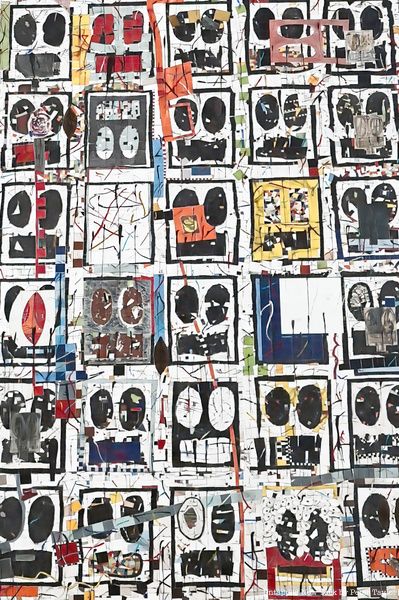

Rashid Johnson‘s mosaic The Travelers’ Broken Crowd features 60 faces looking out from a wall, many of which appear anxious or agitated. Visible from three layers, the 45-by-15-foot mosaic depicts the title “Broken Men” seeing and being seen by travelers. Mostly, the faces consist of just eyes and rectangular mouths assembled from irregular ceramic pieces. Many of the faces are covered, whether by bright tiles, cracked pieces of mirror, oyster shells, or abstract illustrations. A few of the faces are overlayed by smaller faces with less discernable features, and the work also uses a combination of black soap and black wax as a suggestion of sensitivity.

Johnson, who now lives in Manhattan and Bridgehampton, aimed to produce a kind of stability within the piece, capturing the concerns of the present moment and the future. The work should continue to teach people every time they pass by, even amid different temporalities. Many of Johnson’s pieces fit into the genre of post-black art, which ties together race and racism in a way that seems to dispel notions that race matters. After first gaining attention at the Freestyle exhibition at Harlem’s Studio Museum, Johnson would go on to have solo exhibitions at SculptureCenter in Long Island City, Drawing Center in Manhattan, and Storm King Art Center. He has artworks at many major New York City museums and recently showcased his Untitled Broken Crowd at Brookfield Place.

Pacha Cosmopolitanism Overtime is a work by Ronny Quevedo that explores the parallels between local and international migration and movement in sports. To Quevedo, sports are a way of celebrating and making space for oneself, where rules are malleable and transform over time. Sports have allowed him to connect with his ancestry in Ecuador and maintain some semblance of identity while feeling pressure to conform as an immigrant. Quevedo, who grew up in the Bronx, often accompanied his father (who played for a professional soccer team in Ecuador) at games he refereed throughout the city.

Quevedo’s soccer-infused past inspired his artwork at LaGuardia which reimagines a wooden gym floor mounted on a wall. The painted lines that denote the free-throw line and half-court are distorted abstractly to reveal New York’s diverse communities and its constant changes. An important element of the artwork is the use of gold and silver leaf for stellar constellations, which comments on a sense of resiliency among migrants who move like the stars. Quevedo has had solo exhibitions at the Queens Museum, the James Fuentes Gallery, and the Rubber Factory, among other places in New York. He has also been featured at The Whitney, Socrates Sculpture Park, and the Museum of Modern Art. His new work at LaGuardia relates to his previous installation “There is no halftime,” which was at the Queens Museum and had a similar design and theme.

Located by the baggage claim, Mariam Ghani‘s The Worlds We Speak uses data visualization techniques to capture New York’s diversity and is her first tile mosaic. Evoking visions of space, the mosaic is divided into six clusters, representing New York’s five boroughs and the tri-state area, and each contains smaller circles depicting the more than 700 languages and dialects spoken in New York. The circles are all different colors and include the name of the language in English and in the language’s script. Data was collected from the last census and the Endangered Language Alliance.

Ghani, an Afghan American, reflected that the airport is a gateway for speakers of hundreds of these languages, all coming together from different parts of the world. Ghani hopes that passersby can see their language and also learn about the multitude of other languages represented. Ghani is the daughter of Ashraf Ghani, the 5th president of Afghanistan who led the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan before it was taken over by the Taliban. Her works have included Index of the Disappeared, a record of the U.S.’s detention of immigrants after 9/11, and The Trespassers, a documentary examining the problems of language translation.

Mother by Fred Wilson sits in the arrivals and departures hall as a set of 12 globes suspended in a three-story atrium alongside 24 six-foot black drips. Despite supply chain issues, Mother has been progressively installed at the airport to comment on the beauty and fragility of the earth, as well as its complex history. The globes feature black oceans and no country names, alongside an absence of borders, as a reflection of how people get wrapped up in their relationships with others without seeing the larger picture. The sculpture’s black drips, which are made of glass, can be interpreted as representing ink, tar, and even oil, which denote histories grouped with the Black experience.

The many globes and black drips reveal the significance of ecology and preservation of the earth. Wilson has never hand-painted his works until this one, and he decided that all globes should be hung on different axes so each provides a different perspective of the earth. Wilson, a Bronx native, stresses through his art that changes in context create changes in meaning, playing with light, sound, and unconventional pairings to comment on issues of race and power often absent from museums. He represented the U.S. at the 2003 Venice Biennale and became a Whitney Museum trustee in 2008.

Aliza Nisenbaum‘s The Ones Who Make It Run depicts 16 essential workers from Port Authority and Delta Air Lines who make operations run at LaGuardia. The large-scale painting, which was installed as a mosaic, depicts pilots, customer service agents, flight attendants, and taxi dispatchers. Nisenbaum put a face to the everyday workers who are often behind the scenes making flights possible, selecting the 16 figures from a larger pool of employees. Each portrait accurately depicts the inspirational figures based on photographs and Zoom interviews.

Nisenbaum, who lives in Queens but grew up in Mexico City, took inspiration from Mexican muralists Diego Rivera and David Siqueiros for her work. A vinyl reproduction hangs in Concourse F while the future mosaic is built. Nisenbaum said the airport forces people to share space with strangers and have a heightened sense of responsibility for respecting others, sometimes gaining an understanding of the nuances of others’ personalities. The artwork is the only one behind Delta’s security checkpoint, reminding workers of their importance.

Next, check out the Art of Grand Central Terminal!

Subscribe to our newsletter