Before Prohibition and the growth of large national brewing companies like Anheuser-Busch, Brooklyn was one of America’s busiest brewery capitals. In Bushwick alone, there were as many as 45 breweries operating in the 19th century. The large population of German immigrants who settled in Brooklyn found it to be a perfect spot to brew beer partially because Brooklyn’s soft soil made it easy to dig the underground cellars needed for lagering – the cold storage of beer during fermentation. While Prohibition brought an end to Brooklyn’s booming beer industry, the remnants of that golden age of ale – including the abandoned beer vaults – can still be seen inside the William Ulmer Brewery complex. On a recent tour led by Jordan Rogove, DXA Studio Co-founder and Partner, Untapped New York Insiders got to go inside the partially abandoned brewery buildings to learn all about the beer-making process and the restoration of the site.

The Ulmer brewery was founded by pioneering brewmaster William Ulmer, a German native who immigrated to America in the 1850s. He started his beer-making career in another New York brewery owned by his uncles, Henry Clausen Sr. and John F. Betz. Eventually, Ulmer left the family business to start his own venture with partner Anton

Vigelius. Vigelius, who was in the produce business, purchased a parcel of land at the corner of Beaver and Belvidere Streets in 1869 and sold half of the interest to Ulmer. By the 1870s, Vigelius & Ulmer Continental Lagerbier Brewery was established.

The brewery complex was constructed in four phases between 1872 and 1890. The buildings Ulmer left behind give a glimpse into his beer-making process. The storage of grain, the malting, brewing, and lagering (or storage), originally took place completely within the main 1872 brewhouse. “For me, the most interesting discovery was how different the beer-making was in this pre-prohibition period and before electricity became widely available,” explains Rogove, Co-founder and Partner at DXA Studio, the firm in charge of restoring the complex, “There were no pumps as we have today, so the raw materials sat at the top, and gravity-based machines drug them down through the building throughout the beer-making process. The building itself was a machine for brewing and it is fun to think of a building as a means of making something so delicious!”

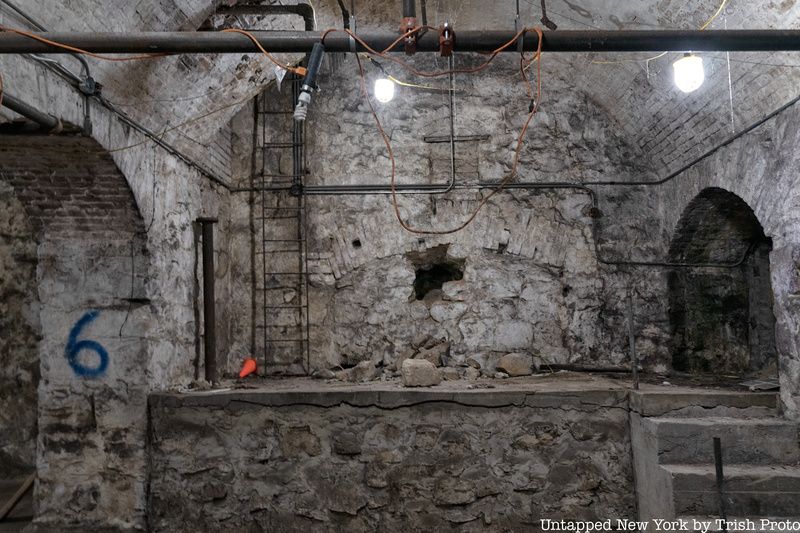

Raw materials at the top of the building made their way down through seven levels until finally hitting the lagering vault. “The part of the building that I love the most is the subterranean barrel-vaulted spaces in the cellar that were originally used to store beer kegs,” says Rogove. These 150-year-old abandoned beer vaults, which go down 20 to 40 feet deep, were integral to the beer-making process. The deepest abandoned beer vault contains five chambers with 14-foot tall vaulted ceilings. These cool cavernous spaces were used to store the beer while fermentation occurred. “We are very excited to bring these back to life through restoration and some clever illumination so that they can be shared with the public.”

The cellars held many surprises for the DXA Studio team tasked with the renovation. “We found a very strange cylindrical silo behind some drywall in the lowest cellar level when we first started exploring the space,” Rogove explains, “At first, we didn’t know what it was for—eventually, with the help of our structural engineer, we saw remnants of structural interventions in the walls of the silo and realized that this object was most likely a vertical tunnel later added to the building to excavate the subcellars. It is crazy to think that these massive subcellars might have been added later! Overall, this was a very interesting insight into the means and methods of construction of the late 1800s.”

In 1885, Ulmer hired Theobald Engelhardt, a German-American architect from Brooklyn, to expand the brewery, which by then had become one of most successful in the area. Engelhardt was responsible for many famous Brooklyn buildings including the Eberhardt Pencil Factory complex and St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in Greenpoint, and the former Weidmann Cooperage now the Wythe Hotel. For Ulmer, Englehardt designed a brick office building, boiler and machine houses, and a large addition to the main brewhouse. The complex continued to expand throughout the late 1800s, with brewery architect Frederick Wunder designing a new wagon room, stable, and storage building.

Ulmer’s brewery, like many in the area, fell to the National Prohibition Act, or Volstead Act, of 1920. By that time, Ulmer himself had died. He retired in 1900 and passed away in 1907. His sons-in-law, John F. Becker and John W. Weber had taken over the business. Many of the brewery’s buildings were sold at the start of Prohibition, but the company did maintain ownership of the office, attached wagon house, and storage additions which were used as offices for the family’s real estate business.

While parts of the brewery complex fell into disrepair over the ensuing decades, other buildings were saved by new uses. The large and spacious buildings were well-suited for manufacturing purposes and were home to Artcraft Metal Stamping Corp., a manufacturer of light fixtures, until the 1940s. Alterations were made to the buildings in the mid-20th century and the office building was purchased and converted into a residence in 1985. In 2010, the complex became the first brewery to receive a New York City Landmark designation. In 2017, the complex was purchased by the Rivington Company. Since then, DXA Studio has been working with the Landmarks Preservation Commission and State Historic Preservation Office to restore the structures and convert them into housing and retail spaces.

“The complex that still stands today is one of the best remaining examples of the American Round Arch and Romanesque Revival Styles,” says Rogove, “Its specific building style helped create an identity for beer-making at the time.” That unique brewery character will be incorporated into the new design. “The beer-making process, and the materials used in that process, feature prominently in our design,” says Rogove, “For example, the rooftop addition is derivative in nature to the materiality of historic copper beer tanks, as well as the metals that are seen in the building’s historic structure. We also made use of a lot of wood, which refers both to the building’s timber framing, as well as the barrels that once stored the beer. We learned a lot about the early beer-brewing methodologies while working on this renovation—it has been a lot of fun to discover this part of the city’s history and incorporate it into our designs.”

Many of the historic materials that will be incorporated into the new designs come directly from the historic buildings themselves such as original cast-iron columns and tin ceilings. Rogove also points out that “the old fire and entry doors are also being retained throughout the building, so occupants will have even more opportunities to interact with the building’s history.”

DXA Studio’s renovation will mark the third reinvention of the William Ulmer Brewery complex. The project is featured in the first monograph of DXA Studio’s work, DXA Ten Years. Today, the legacy of Brooklyn’s breweries lives on in historic buildings like this that are restored and find new uses, and the many micro and craft breweries that have opened in recent years. Check out more photographs from our Untapped New York Insiders visit to the William Ulmer Brewery and its abandoned beer vaults in the gallery below and join us for an exclusive photo tour where you can take your own snapshots before this space is changed forever.

Next, check out The Smallest Commercial Brewery in the World at Coney Island