Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

For most people, Liberty Island is a tourist destination. For a young Carol Tuzzolo, however, it was her home.

For most people, Liberty Island is a destination. A place to visit for a few hours and check off your bucket list. For a young Carol Tuzzolo, however, it was her home. For seven years of her life, through the duration of World War II, Carol was a resident of Liberty Island, or Bedloe’s Island as it was called at the time. Carol’s father, James Bizzaro, was the Statue of Liberty’s head of maintenance, a job that brought the whole family – including Carol’s mother and three older siblings – out to the island. Carol passed away in the summer of 2023, but Untapped New York had the pleasure of speaking with her in 2022 on a video call from her home on a different island, Long Island. Then an 85-year-old great-grandmother, Carol remembered her time at Liberty Island fondly. We listened as she entertained us with tales of her daily treks up to the Statue of Liberty’s crown, her adventures crabbing on the Hudson, and the difficulties that come with living at one of America’s most famous tourist attractions.

James Bizzaro, Carol’s father, was the head of maintenance for the Statue of Liberty for 36 years. According to his obituary in Newsday, he originally came to the island as a guard but “didn’t enjoy wearing a uniform.” Since he had a background as a plasterer, he asked to assist whoever was responsible for the statue’s maintenance. “My father knew a lot about everything,” Carol remembered. From then on, Lady Liberty became James’ statue. Bizzaro took responsibility for everything, from electricity and plumbing to repairing the copper sheathing and changing the lights. Carol said he even turned the lights green for St. Patrick’s Day! “He did everything. He called the statue ‘My Lady,’ ‘My Statue.’ It was his statue. I always say the same thing, my island.”

Bizzaro and his family lived in a home behind the Statue of Liberty, a short distance from the crowds of tourists who would visit every day. Carol remembers that there were three houses occupied at the time she lived there, though she and her siblings were the only children around the same age. “The visitors were always in the front, but the rest of the island was ours. We could do whatever we wanted,” said Carol. As children, they had the best playground in New York City.

Once she was old enough, Carol climbed more than 160 steps up into Lady Liberty’s crown every day. “I used to eat my lunch in the crown,” she remembered, “Everybody would look at me because I would be sitting there in the middle of everyone. And then, they would try to follow me because there was a rope all around that I would go under it to leave. The visitors would ask ‘How come she gets to go there?’ and the guard would say. ‘Because she can.'”

Carol’s favorite place on the island was inside the statue. Her mother, on the other hand, chose to stay on the ground. The one time her mother did ascend to the statue’s torch, Carol’s brothers made it rock back and forth. Their mother was so scared, she never went up again.

“I knew everybody who worked on the island and they all knew me because I was the youngest,” Carol recalled. She especially enjoyed the company of a young boy named James Hill. Hill’s family owned a concession stand on the island and Carol remembers Jim always being kind and playful with her. He would put her up on his shoulders and walk her around. She also fondly recalled a boat driver, who she called Uncle Sam, who used to let her “drive” the boat to Manhattan. The Shore Patrol officers were a different story. Little Carol delighted in being a bit mischievous when the officers would come around. The “SP” on their uniforms, she would tease, stood for “Sourpuss.” “I must have been some kid,” Carol laughs, “I had fun,” darting away from the officers and hiding where they couldn’t find her.

Carol and her siblings explored all over the island. She remembers finding remnants of the island’s past as a military fort. “My sister and I both had our own truck, but they had no wheels. And we had our own house. We used to get in our truck and pretend, “Oh let’s go visit Aunt so-and-so. It was wonderful!”

Since Liberty Island is, after all, an island, the children would also take part in water activities. Nearly every day they would walk along the seawall and get sprayed with water as the waves crashed against it and their mother yelled for them to get down. They would fish and catch crabs too. “When I was older about 14 or 15 and I would go crabbing with [the boy who would become my husband], he was scared of the crabs! I would say you just put your foot on it and grab it. I knew how to do it from the island,” Carol said.

Even though there were only a couple of other families who lived on the island full-time, Carol never remembers being lonely. She had a good friend from school, Bambi, who would visit often and there was always family around. “Every week we had company,” Carol told Untapped New York, “The aunts and uncles came out of the woodwork. Everyone wanted to see the Statue of Liberty and we would give them tickets. It was a really nice thing to do.”

While recreation on the island and the incredible views were surely perks, everyday life could get a little daunting. “My father had a boat, so when we ran out of milk or bread, we got in the boat and went to New Jersey. They had a store right on the water where we stopped, got what we wanted, and went back to the island,” Carol recalled. This helped make island life a little easier, but it was still quite a journey to get to other parts of New York City. Carol and all of her siblings attended Catholic school at St. Alphonsus in Manhattan. To get there from Liberty Island, they had to take a boat into Battery Park and then a bus to the school. One day in the first grade, Carol missed the bus and almost didn’t make it back home to Liberty Island. “I could see it going and thank God it stopped for a red light. I knocked on the door and the bus driver let me in. My three siblings would have been in some trouble.”

When Carol’s oldest brother was about to start high school, the commute became too much to handle. The children had to rely on a ferry to get them to Manhattan and if the sailing conditions were dangerous, the ferry wouldn’t run. Not wanting the children to miss school, the Bizzaros moved to Brooklyn, their home before Liberty Island. In Cypress Hills, Carol traded Lady Liberty for a new neighbor, a seven-year-old boy who would later become her husband!

Carol’s family wasn’t the first – or last – to live on Liberty Island. For Native Americans, Liberty Island was one of three “Oyster Islands” that were used for oyster harvesting. In 1667, Dutch colonist Isaac Bedloe took ownership of the island, which was taken over by the British within a decade. By 1738, New York City had possession of the island and used it as a quarantine station. It would be used on and off as a quarantine and isolation station throughout the next half-century. In 1807, construction began on a military fortification, Fort Wood. Service members and their families were stationed at Fort Wood until the 1930s.

Even after the military gave up control of the island to the National Parks Service in 1933, employees at the Statue of Liberty and their families continued to live on the island. According to Jeffrey S. Dosik, a librarian with the Parks Service on Ellis Island, the last of Fort Wood’s buildings were torn down by 1956. The last residents of Liberty Island, Superintendent David Luchsinger and his wife, Debbie, left the island in 2013. The Statue of Liberty Museum now occupies the side of the island where the residences used to be.

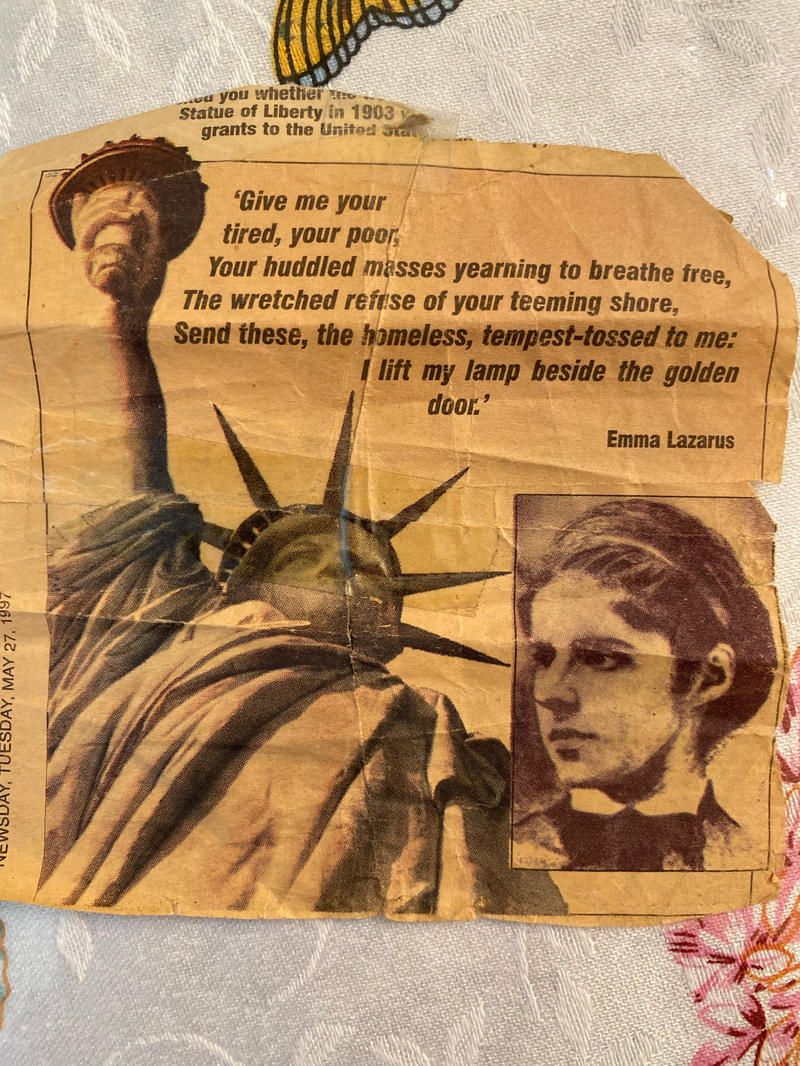

As we spoke, Carol was surrounded by stacks of photos, albums, newspaper clippings, and Statue of Liberty memorabilia that her father had collected throughout the years. She excitedly showed us everything from a collective teacup and saucer set to an actual metal piece of the statue. Among the ephemera, there were also letters written in squiggly crayon writing. She used to travel around to her grandchildren’s classrooms to tell her story of life with Lady Liberty and in return, she’s received dozens of handmade thank-you notes from the schoolchildren.

Despite her love for Liberty Island, once Carol’s family left in 1945, she only returned twice. Once, in 1971 for her father’s retirement party at the base of the statue, and another time by accident. “I had five children and I didn’t have babysitters like they have today,” Carol recalled. In order to attend the retirement party for her father, nuns from school stepped in to watch her children. On her second visit to the statue, she ran into an old friend.

Carol was traveling with a group of girlfriends to Ellis Island, and wasn’t aware that the boat was going to stop at Liberty Island first. When the ferry pulled in, “I just got crazy,” Carol said, “I started telling them all these things about the statue and they thought I was full of it.” Eventually, she walked up to an employee and asked to see Jim Hill, the young boy who used to carry her around on his shoulders. He was all grown up now and still running the concessions on the island. When she told Hill who she was, he lit up. “He hugged and kissed me and introduced me to his son, and the girls went ‘Oh my God, she’s telling the truth!'” Turns out, people think you’re joking when you say you lived next to the Statue of Liberty. The homecoming is something Carol will never forget, “That was amazing when I stepped on that ground again. I couldn’t believe it.”

Next, check out Top 10 Secrets of the Statue of Liberty

Subscribe to our newsletter