How to Make a Subway Map with John Tauranac

Hear from an author and map designer who has been creating maps of the NYC subway, officially and unofficially, for over forty years!

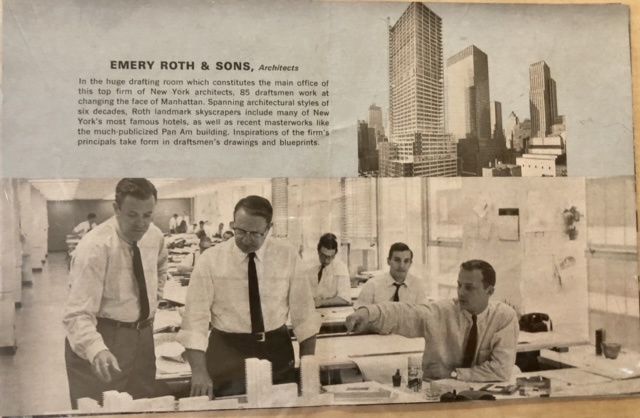

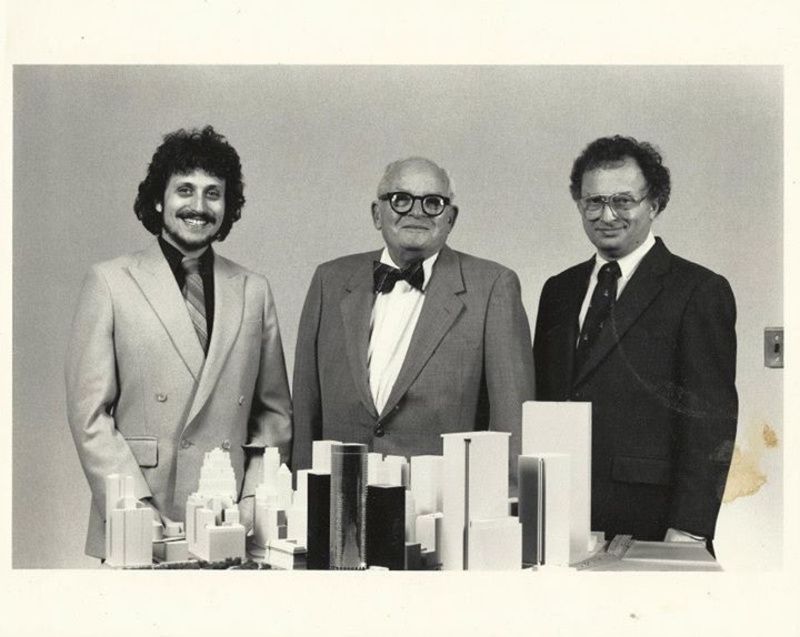

The family-run architecture firm of Emery Roth and Sons has reshaped Manhattan’s skyline many times over. Emery Roth, known for designing upscale, often Art Deco, apartment buildings such as the Beresford, the San Remo, and the Eldorado, founded an architecture practice in 1903. In 1938, he renamed his practice Emery Roth and Sons to represent the inclusion of his two sons, Julian and Richard. The family tradition continued in the 1960s when Richard’s son, Richard Roth Jr., joined the firm and eventually became the chief architect. With each new generation, came new innovative designs and new buildings for New York City.

Emery Roth and Sons was one of the most prolific New York City architecture firms of the twentieth century. According to a list of the biggest architecture firms in New York published by Crain’s in 1994, Emery Roth and Sons buildings accounted for 10.2 million square feet of project space, landing the firm at number 7 of 25. There was a mid-century boom of buildings by the firm that embodied the sleek, modern, Post-war style. These buildings, mostly commercial offices, were designed with curtain walls, public plazas, and lots of glass, steel, and concrete. With the guidance of Richard Roth Jr.’s daughter and Untapped New York Insider Robyn Roth-Moise, we’ve compiled a list of 10 of the most famous Post-war buildings designed by Emery Roth and Sons.

On Wednesday, November 30th, join Untapped New York Insiders, Chief Experience Office Justin Rivers, and Roth family members for a virtual Insider Roundtable: Remembering Richard Roth Jr. This event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. The roundtable will feature a short retrospective of Roth Jr.’s work, never before seen interview clips, and the chance to share your own memories. This event is free for Untapped New York Insiders.

Few New York City buildings are as iconic or recognizable as the Twin Towers at the World Trade Center. While architectural credit most often goes to Japanese-American architect Minoru Yamasaki, the design and engineering of the World Trade Center was a collaborative endeavor by Yamasaki, Emery Roth and Sons, and the Port Authority. In 1962, Yamasaki was selected from a list of dozens of other illustrious architects to design the center. Yamasaki’s Michigan-based firm paired with the New York-based firm of Emery Roth and Sons to get the project done.

In a talk with Richard Roth Jr., available in the Untapped New York Insiders on-demand archive, Roth notes that the firm was most famously known for creating all of the working drawings for the World Trade Center and for the Citicorp Building. The massive project of designing and constructing the World Trade Center complex took over a decade from conception to completion. Later, in 1987, Emery Roth and Sons would return to the site to design 7 World Trade.

Project X was the first project Richard Roth Jr. was assigned to when he entered his family’s firm in 1957. Project X was a high-profile skyscraper to be built behind Grand Central Terminal. Roth was tasked with creating a list of architects for the firm to collaborate with. From that list, Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi were chosen by the developer.

Project X, of course, was the Pan Am Building, now the MetLife Building. In Emery Roth and Sons’ original designs, the building was made of aluminum and glass, reached 57 stories, and ran from north to south. When Gropius and Belluschi came onto the project, the tower was reoriented to run east to west, while granite and pre-cast concrete replaced much of the aluminum and glass of the facade.

You can hear Richard Roth Jr. discuss the design and construction of the Pan Am building in an exclusive sit-down talk recorded for Untapped New York Insiders.

A fun fact about the MetLife building is that it once had a helicopter deck on its roof with service to the Pan Am terminal at JFK International Airport!

The General Motors Building at 767 Fifth Avenue was another major collaborative project for Emery Roth and Sons. This time, the firm worked with architect Edward Durell Stone. Stone was a prolific architect throughout the 1950s and 1960s who designed many buildings in New York City, most notably The Museum of Modern Art, Radio City Music Hall, and an 1878 brownstone renovation. The 50-story tall General Motors building takes up an entire city block and has its own zipcode!

Standing at the southeast corner of Central Park, right across from the Plaza Hotel, the General Motors Building occupies the former site of the 1927 Savoy Hotel. New York Times architecture critic Ada Louis Huxtable noted that it had “the best address in town.” That address has come with a hefty price tag. The GM Building has been sold in multiple record-breaking deals. In 2003 it sold for $1.4 billion, then $2.8 billion in 2008, and it’s current estimated value is over $3 billion.

77 Water Street is among the most playful buildings designed by Emery Roth and Sons. On 77 Water, the firm collaborated with developer Melvyn Kaufman, a favorite of Richard Roth Jr. Kaufman liked to infuse his buildings with whimsical flourishes, and 77 Water in the Financial District is a prime example of his quirky flare.

At the entrance plaza to the 26-story office building, you’ll find a candy store that looks like it was transported from the old wild west. On the building’s roof, there is a full-size model of a World War I-era warplane. The stainless steel model even has its own Astroturf runway complete with landing lights. Why put an installation like this on the roof? Because people in the taller buildings that surround 77 Water Street could see it as they look out their windows.

Citicorp Center was the product of a collaboration between Emery Roth and Sons and Hugh Stubbins and Associates. The top and bottom of this 46-story tower are both unique. The top of the tower is steeply slanted, while the bottom is comprised of a 10-story open platform. The tower floats above this open space atop four 24-foot-square columns. Just a year after the building was complete, a graduate student who was studying the structure discovered that it was vulnerable to strong winds at its corners. This discovery led chief structural engineer, William LeMessurier to do some recalculations, and fortifications to the building were quickly made. This oversight went largely overlooked until it broke in a New Yorker article in 1995.

In addition to the tower, Citicorp Center is comprised of a smaller 8-story office building, a sunken pedestrian plaza, a U-shaped shopping area, and a structure built for the St. Peter’s Lutheran Church (the original was knocked down to make way for the center). The building was designated a New York City Landmark in 2016, the youngest at the time – that honor now goes to the At&T Building, completed in 1984. It also won the firm many awards including an A.I.A. Honor Award, a Design Award from the New York State Association of Architects, Inc. and a Design Excellence Award from the Municipal Art Society.

17 State Street, the curved glass building in the center of the photograph above, is just one of the many buildings designed by Emery Roth and Sons that can be seen from New York Habor. It’s also one of 17 Emery Roth and Sons buildings that were added to the Panorama of the City of New York inside the Queens Museum, a model of the city largely as it was during its last restoration in 1990.

17 State Street is another product of the relationship between Emery Roth and Sons and Melvyn Kaufman. While at first glance, it seems like 17 State Street doesn’t boast any Kaufman-esque whimsy, in 1988 New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger called it “in some ways the most daring building the Kaufmans have yet built in New York.”

The curved front of the building which faces the Battery follows the curve of State Street, allowing all floors a view over the park and to the water. Its flat sides make allow the structure to fit snuggly between the rectangular buildings it neighbors. A light beam that projects from a tiny tower on top of the building gives it the feeling of a sleek lighthouse – there’s the Kaufman touch.

The Lotte New York Palace, which sits across from St. Patrick’s Cathedral, consists of the historic Villard Houses and a 55-story tower designed by Emery Roth and Sons in Midtown East. The original owner of the hotel was real estate mogul Harry Helmsley. In an Untapped New York Insiders talk all about Roth-designed hotels, Richard Roth Jr. recounted a conversation between his father and Helmsley. Roth said he would only take the job of designing the hotel if the landmarked Villard Houses were saved. Luckily, Helmsley didn’t want to knock them down.

Once the tower was complete, the Helmsleys were satisfied – for the most part. There was one peculiar problem. As Richard Roth Jr. told Untapped New York Insiders, Leona Helmsley complained that people were falling off the hotel’s toilet seats! When he tested the seat himself, Richard Roth Jr. found they were the “cheapest piece[s] of nonsense ever.” The firm’ specifications called for the best wooden toilet seats, so the contractor must have cut some corners. While Richard’s involvement in the toilet seat debacle was over at that point, he’s sure the “Queen of Mean,” as Mrs. Helmsley came to be known, took care of it. Richard Roth Jr. said he always had a good relationship with Mrs. Helmsley.

Richard Roth Jr. told the New York Post in 1988 that he turned down a Samuel Rudin project that would require the demolition of the Villard Houses. When the Rudin Organization approached Emery Roth and Sons again, with a proposition to design a tower at 345 Park Avenue, he took the job. “I was very cognizant of building between two great architectural masterpieces – the Seagram building and St. Bart’s,” he told the paper.

Roth goes on to explain that he designed 345 Park with a low-story building on its north side that pays deference to the Seagram’s plaza, and 345 Park’s plaza opens up to St. Bart’s on the south side. The building houses Rudin Management’s headquarters and is one of many that Emery Roth and Sons designed for the company, including 80 Pine Street, 94 Fifth Avenue, 215 East 68th Street, and 136 East 55th Street.

488 Madison was formerly known as the Look Building for its original primary tenant Look magazine. It was designed by Emery Roth and Sons for the Uris Brothers development company. The 21-story building sits between 51st and 52nd Streets.

The Look Building exemplifies the transition of architectural styles that was happening at the time. It’s setbacks adhere to the 1916 zoning law that set the standard for Art Deco buildings of the 1930s and 1940s, while its sleek materials of give it a more streamlined and modern feel. The building was designated a New York City landmark in 2010.

In a talk about the hotels of Emery Roth and the family firm, Richard Roth Jr. told Untapped New York Insiders that Harry Helmsley wanted an apartment in New York City with unobstructed views of Central Park. This desire led to the creation of the Helmsley Park Lane Hotel, now simply called the Park Lane Hotel, at 36 Central Park South.

The hotel was threatened by redevelopment in 2014 prompting the formation of a Save Park Lane Hotel campaign. Though the building has still not been landmarked, it also hasn’t succumbed to redevelopment. In fact, the hotel recently underwent an extensive interior renovation, reopening in 2021 with designs by the international studio Yabu Pushelberg. With the fresh new look comes fresh new restaurants and a rooftop bar with stunning park views.

Next, check out The New York Apartment Where Emery Roth Lived and Top 10 Secrets of the MetLife Building

Subscribe to our newsletter