Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

You may expect remnants of New York City’s colonial history to be hard to find or cordoned off behind barriers and glass, but there are many vestiges of the past integrated into today’s modern cityscape. Most are easily accessible on a walk through Lower Manhattan.

While some remnants are visible but out of arm’s reach, like the 17th-century remains of the Lovelace Tavern, there are pieces of the city’s colonial history that you can literally reach out and touch! Hidden in bars, embedded in the walls of a subway station, and simply out in the open air, here are 10 physical remnants of colonial Manhattan you can touch:

It is well known that the New York City subway system is full of fun and interesting art pieces, but inside the South Ferry Station, 1, R, N, W, and 2 train riders will find something very unique: the remnants of an 18th-century stone wall. This chunk of stone was one of four wall fragments discovered below the eastern part of Battery Park in December 2005 by the Museum of the City of New York’s archaeological team. As the team was conducting excavations for the South Ferry Station, they came upon one of the oldest man-made structures still in place in Manhattan, the Battery Wall.

The wall was built around 1755 at the southwestern tip of Manhattan to shield the colony, then under British rule, from enemies as well as rough waves and wind. The wall was buried under a landfill in the late 18th century and further buried by Battery Park in the 19th century. Today, you can walk right up to the wall and touch it. You can even see fossilized oyster shells embedded in the stones.

Get your hands on these remnants when you join our expert-led walking tour!

The largest remnant of Dutch New Amsterdam, and one of New York City’s largest designated landmarks, is the street grid of the Financial District. The street layout of Lower Manhattan appears today largely as it was in the 17th century, so you can quite literally walk the same paths as the earliest colonial New Yorkers. One of the streets even runs through a modern building.

This original grid can be seen on the Castello Plan, a 1660 map of Dutch New Amsterdam. On the map, you’ll see street names like Begijn Gracht, Paerel Straet, and Brugh Straet. These names might not seem familiar at first glance, but their anglicized names are more recognizable: Beaver Street, Pearl Street, and Bridge Street. When the British took control in 1664, they changed many of the street names but kept the layout the same. Discover 10 streets from the original colonial NYC street grid here. A bronze sculpture of the map can be found at State Street, between the Staten Island Ferry and Whitehall Street.

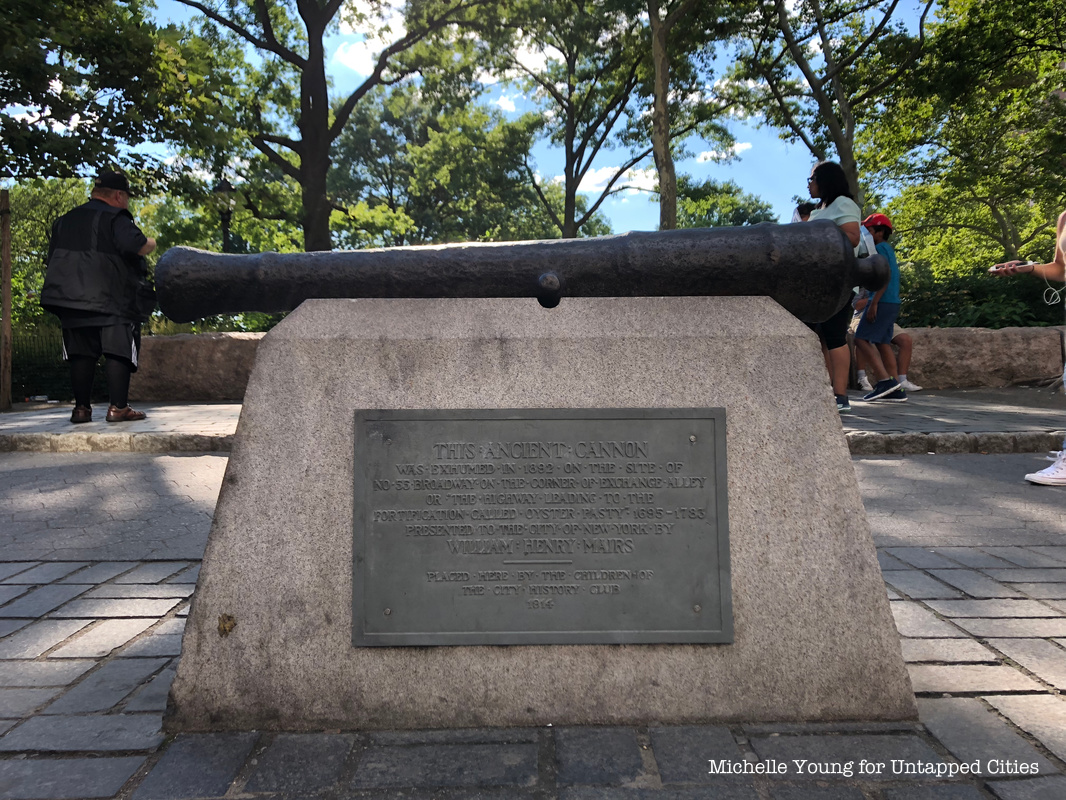

Untapped Cities’ Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers believes that this artifact is the oldest European artifact in Manhattan, meaning the oldest item that was built here by Europeans, not brought over from Europe. The Battery Cannon was dug up in 1892 at Exchange Alley and Broadway during construction. A plaque on the cannon’s mount notes that Exchange Alley was formerly used as the path to British fortifications called “Oyster Pasty.”

Rivers says that the Oyster Pasty mount can be seen on the Castello Plan, which dates back to Dutch New Amsterdam in 1660. The cannon was donated to the City of New York by William Henry Mairs and relocated to Battery Park in 1914. You will find the cannon at the perimeter of the park on State Street between Bridge and Pearl Streets. It is not uncommon to find people using it as an unconventional seat (though we advised against this!). Discover more historic cannons around New York City here!

New York City’s oldest park also boasts the city’s oldest fence. Throughout its over 400-year history, Bowling Green has served as council grounds for Native American tribes, a parade field, a cattle market, and an actual bowling green for lawn bowling. The fence around the park was erected in 1771 when New York was under British rule. The centerpiece of the park was a statue of King George III.

As the Revolution drew near, the park became a popular site for anti-English protests. The fence still bears the marks of one notable revolutionary act. The fence posts were originally topped with crowns that were defiantly sawed off by revolutionists. The revolutionists also took down the statue of King George III and melted it into bullets. You can rub your hands along the tops of the fence posts today to feel the jagged cuts. Find out where in New York City you can see pieces of the King George II statue!

The cobblestones of Stone Street date back to around 1655, when the road became the first in the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam to be paved. Legend says a wealthy brewer’s wife who lived on the street was fed up with dust from the street being kicked up by horses and ruining her drapes, and got Peter Stuyvesant to pave the street. The street has gone by many names throughout its history based on whoever owned it.

Known to the Dutch as Hoogh Straet or High Street and later Brewer Street, the English renamed it Duke Street. In the midst of anti-English sentiment that followed the American Revolution, many English street names were replaced. Duke Street became Stone Street in honor of its status as the first paved road, which you can still walk on today. Discover the hidden meaning behind more New York City street names here.

Standing in the shadow of the modern skyscraper of One World Trade, St. Paul’s Chapel holds the title of the only colonial church still in Manhattan. Built in 1766, St. Paul’s was one of two chapels built for Trinity Church, the second being St. George’s, which burned down. St. Paul’s almost met a similar fate in the Great Fire of 1777, which destroyed around 500 buildings, but luckily it was saved. The original Trinity Church was lost in that fire, so St. Paul’s became the congregation’s primary church.

George Washington regularly attended services at St. Paul’s until Trinity Church was rebuilt in 1790. In fact, he went to St. Paul’s right after his inauguration at Federal Hall, just a short walk away, in 1789. He sat in a specially designated Presidential Pew. While the pew is no longer there, a painting of one of the earliest known representations of the Great Seal of the United States, commissioned in 1789 to commemorate Washington’s inauguration still hangs above the site where he would have sat. The church is full of original architectural details and a very special monument to General Richard Montgomery. Montgomery was a Revolutionary War officer and the monument to him at St. Paul’s was the first commissioned by the Congress of the United States.

Another piece of the colonial Battery Wall can be found at Castle Clinton. This piece has more dimension than the one-sided display in the South Ferry subway station. At Castle Clinton you will find an L-shaped bastion that researchers surmised likely projected outwards towards the water, creating a strategic place to position weapons that could be fired in several directions.

Castle Clinton was one of four forts constructed to prevent a British invasion in 1812. It also served as America’s first immigration station, prior to Ellis Island. Between 1855 to 1890 more than 8 million people entered the United States through Castle Clinton. Since then, the fort has served as a beer garden, theater, and public aquarium over the course of its life. Today it is a National Monument that you can visit.

Perhaps one of the more surprising places you’ll find a remnant of colonial NYC is on your way to the bathroom inside the Stone Street Tavern. Located at 52 Stone Street, the tavern’s building was constructed in 1836, likely after an original structure was burnt down in the Great Fire of 1835.

The new building was constructed on top of an 18th-century foundation. You can still see part of the foundation in the stairwell that leads to the current restaurant’s lower-level restrooms. The Stone Street Tavern is a favorite of Untapped New York’s Chief Experience Officer Justin Rivers and a perfect spot to grab a drink after joining Untapped New York’s remnants of Dutch New Amsterdam tour!

Fraunces Tavern holds the top spot on the list of Manhattan’s oldest buildings. The tavern was also one of the first buildings to be designated a New York City Landmark in 1965, though much of the original colonial structure is non-existent. There has been a structure located at the site since 1719 when it was originally built as a private residence for Etienne DeLancey. In 1761 Samuel Fraunces, from whom the building takes its name, bought the building and opened the Queens Head Tavern.

The tavern played a significant role in the American Revolution, serving as a meeting place for revolutionary groups like the Sons of Liberty and as a residence for George Washington during the final days of the war. However, after a restoration in 1906, much of the original structure was lost or obscured, and there was a lot of guesswork in recreating the original structure. There are however some pieces of the original structure that survive. On the west wall of the tavern, there is 18th-century Holland Brick and inside, there are original oak-hewn beams in the floors and ceilings of some of the upper rooms, including the famous Long Room.

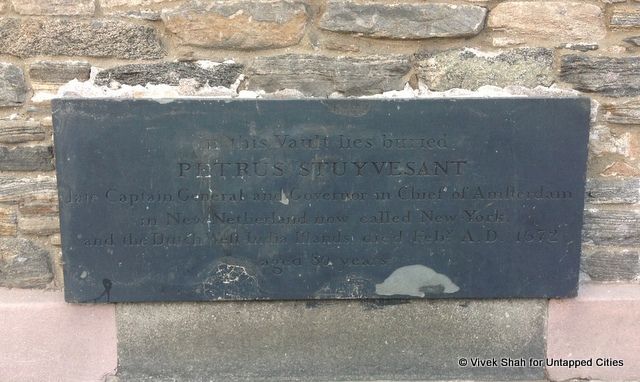

Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch governor of New Netherlands, is buried beneath St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, one of the most allegedly haunted spots in New York City. The current site of St. Mark’s was previously occupied by Bouwerie Chapel, a private chapel built for the Stuyvesant family on their farm. When Stuyvesant died at the age of 80 in 1672, he was interred below the family chapel. Stuyvesant and generations of his heirs that followed are entombed in the Stuyvesant vault.

Though the marker on Stuyvesant’s grave dates to the early 20th century, the vault within dates to his death in the 1600s. While you can’t literally touch this relic, you can still see the physical vestiges of the old Stuyvesant chapel in the orientation of the current church. St. Mark’s Church-in-the-Bowery, consecrated in 1799, faces South, as the original Stuyvesant chapel did, even though this is at odds with the City’s current grid, which grew north to meet it.

To visit some of these sites for yourself and to learn more about colonial NYC history, join Untapped Cities for an upcoming Remnants of New Amsterdam Tour!

Learn more about NYC's Dutch history as you trace the original street grid.

Next, check out 10 NYC Streets from the Original Dutch Colonial Street Grid and The Top 7 Oldest Buildings in Manhattan

Subscribe to our newsletter