Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Fulton Fish Market, the largest collective of seafood wholesalers in the United States, has a long and storied history that spans from 19th-century Lower Manhattan to the modern-day Bronx. In his new book The Fulton Fish Market: A History, author Jonathan Rees takes a look back at the market’s evolution. Covering topics from the influence of organized crime and advancements in technology to the city’s infrastructure and the development of the South Street Seaport historic district, Rees’ book explores how an everchanging New York City affected the fish market and how the fish market adapted to those changes, overcoming various cycles of failure and success to continue thriving to this day. We revisited our 2019 visit as well as consulted Rees and his book to bring you our favorite secrets of the Fulton Fish Market:

On January 5th, join Untapped New York Insiders and author Jonathan Rees for a virtual talk on the history of the Fulton Fish Market! This event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. If you’re not an Insider yet, become a member today (and use the code JOINUS to get one month free).

The original Fulton Market Market along the East River didn’t always sell only fish. The market opened on January 22, 1822, and catered to customers from Manhattan as well as those coming from Brooklyn and Long Island via the ferry. 19th-century shoppers could purchase all types of food items, from meat and poultry to fruits and vegetables. The Fulton Market was just one of many general food markets operating throughout New York City at the time. It wasn’t until 1869 that the fish sellers would get their very own permanent building.

It took decades for the Fulton Market to transform into the Fulton Fish Market. The change happened gradually until all of the other retail grocers left and only the wholesale seafood market remained. Many factors contributed to this shift. One major factor was the diversion of people away from the ferries. The Fulton Ferry stop was initially a benefit of the market’s location because it led to high foot traffic. However, once the Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883, fewer people used the ferries. By 1924, the ferry dock was closed.

Another change was the expansion of Manhattan northwards. Residents who did their usual grocery shopping at the market moved further uptown and the area became less residential. With the growth of different neighborhoods, more local grocery stores popped up closer to homes. Eventually, after the other vendors left, the market “became an internationally recognized place for buying and selling seafood of all kinds.” The Fulton Fish Market was the only place in New York City where seafood could be bought wholesale.

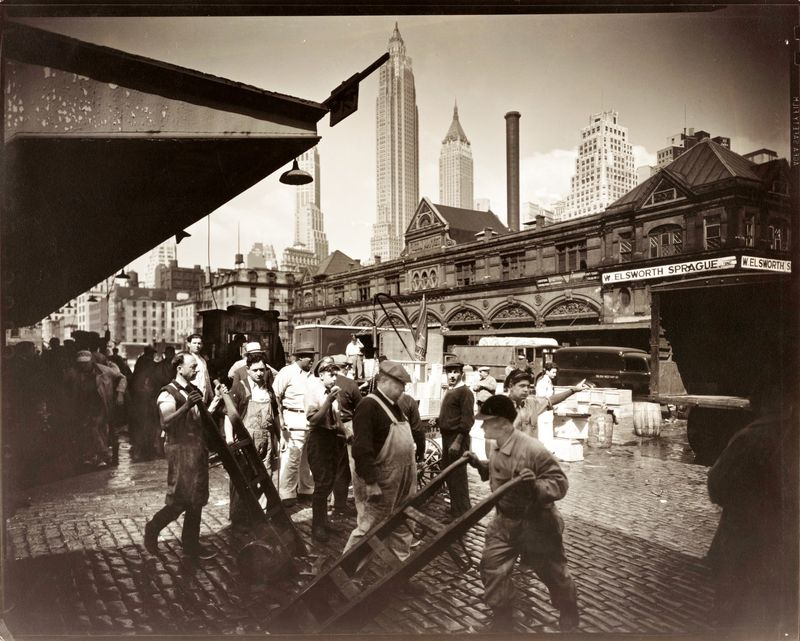

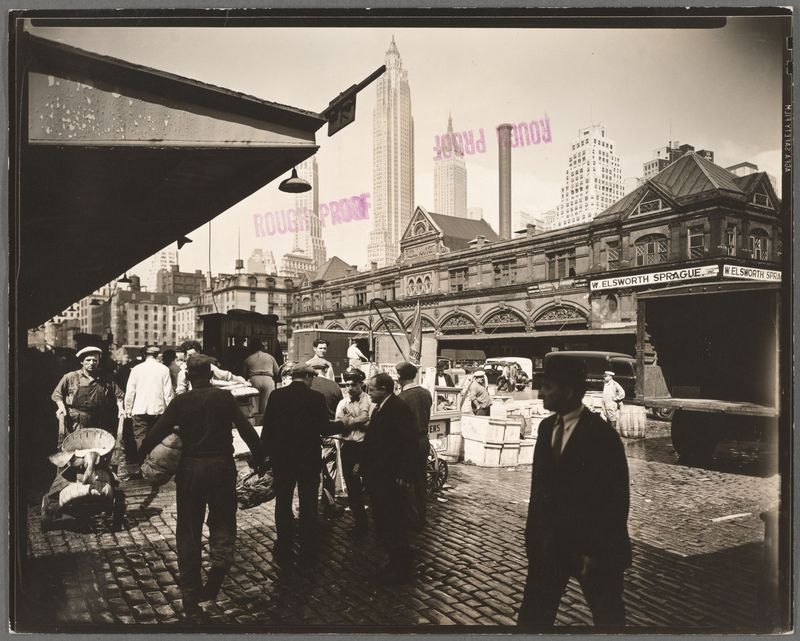

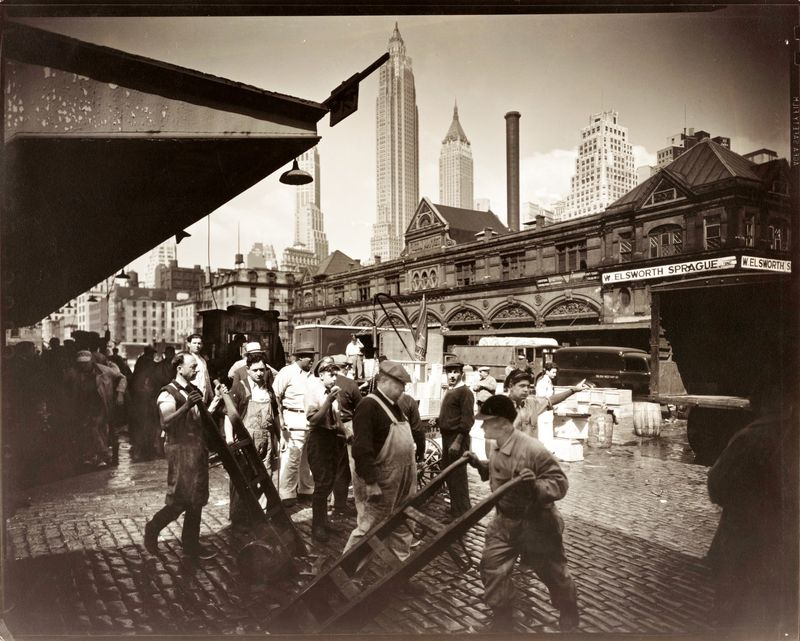

At its height, the Fulton Fish Market stretched over “six city blocks bounded by South and Water Streets on the east and west and Fulton and Dover Streets to the north and south,” write Rees. Throughout its history, it occupied many different buildings in the area until a major move to a new, modernized facility at Hunts Point in the Bronx in 2005. The Fulton Market’s original location opened in 1822. It was bounded by Water Street and South Street to the north and south, and Beekman Street and Fulton Street to the East and West. In 1831, the fish business had grown so large that some vendors moved into a new building between Piers 17 and 18 on the East River. While retail fish sellers remained in the main market building, wholesalers began to take occupy shed structures along the river.

In 1869, the Fish Market moved into its first dedicated, permanent building between South Street and the river. The building was constructed by the Fulton Market Fishmongers Association, an organization of the largest fish sellers. The new building, designed specifically for their wholesale operations, was a two-story wooden structure with a cupola on top. There were seventeen fish stalls on the first floor and offices, storage space, and a reading library on the second. The original 1822 market building was struck by fire in 1878 and replaced in 1883, by the brick building pictured above. This building was demolished in the 1950s and replaced with the 1983 Fulton Market mall we have today.

In 1907, another new building was constructed, known as the Tin Building (even though it was made of steel). Sitting between Piers 17 and 18, the building’s position right on the water allowed for boats to pull directly up to it. Dealers who didn’t get space in the Tin Building banded together to build their own in 1909. Both buildings were doomed. The 1909 building fell into the river in 1936 when a piling gave way. There were rumors that a fishing boat piloted by a drunk captain crashed into the piling. Luckily, there were no casualties as the incident happened outside of business hours. The 1907 Tin Building was set on fire by arsonists in 1995. In 1939, at the behest of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, The New Market Building was constructed. LaGuardia was gifted a 300-pound halibut at the opening ceremony. This building now sits abandoned and is slated for demolition.

“The exact origin of mafia involvement in the fish market is obscure,” writes Rees, but by the 1920s, fish dealers were making payments to the mob to insure that their fish wouldn’t be stolen by the union workers who unloaded and loaded it. This unloading process is where the mob found its power. If fish weren’t unloaded properly and just left to rot, a fish seller would lose business. Joseph “Socks” Lanza, a man closely tied to the Genovese crime family, created the Seafood Workers’ Union local at the Fulton Fish Market, known as Local 359. In his book, Rees notes that “by 1925, half of the laborers in the market were Italian Americans, and Lanza became their business agent.”

The involvement of the mafia started a media frenzy in the 1930s when New York’s District Attorney investigated claims of racketeering and grand juries tried extortion charges. It became known that Lanza was forcing wholesalers to pay for protection against the vandalism of their trucks and the theft of their goods. Lanza’s union was also charging sellers extra landing and trucking fees that he claimed went to the union’s “benevolent fund.” Lanza was ultimately convicted of racketeering and extortion and was sentenced to seven to fifteen years in prison. Despite his imprisonment, the Genovese family maintained a tight grip on the market. The market’s mafia ties came to light again in the 1970s and 1980s when Carmine Romano was convicted of racketeering. The union had convinced fish wholesalers to hire a private security firm to protect themselves from the mob influence. The company they were persuaded to hire was actually controlled by the mob, and payments were going to Romano. New regulations and the break up of the unloading monopoly in the 1990s helped sellers come out from under the influence of the mafia.

One of the most theatrical sellers in the Fulton Fish Market was Eugene Blackford. Blackford likely developed his penchant for salesmanship and showmanship working for department store magnate A. T. Stewart. Near his stall at the Fish Market Blackford displayed strange and exotic fish that attracted customers. Near his office, on the second floor, he created the Fulton Market Fish Museum.

In the museum, Blackford displayed all sorts of aquatic oddities. There was a bright green parrot fish, the head of a giant turtle, an iguana, and a lung-nosed gar, among other specimens. Blackford would go on to help found the New York Aquarium at Castle Clinton in Battery Park in 1896. He also helped to create New York State’s Hatchery Station at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island,

Though turtle steak and turtle soup never became staples of New York City diets, they were attractive novelty dishes in restaurants of the 19th century. For sellers of the turtles, they were a profitable product. Turtles were rare and expensive. To keep the turtle meat fresh, turtles were kept alive during transportation and at the market. When they arrived at the Fulton Fish Market, the turtles were tied up at the piers, and often their mouths are tied shut because they were known to snap at and bite people who got too close. It was the responsibility of the buyer to kill the turtle before cooking it. Since green turtles could be anywhere from 15 to 350 pounds, this was not a simple task.

In 1866, after founding the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), Henry Bergh brought cases against turtle sellers for their cruelty towards the animal. While none of the charges stuck, there were slight modifications to the way turtles were handled. The sale of turtles ended in the 1970s when they were certified as an endangered species.

One of the historic former homes of the Fulton Fish Market, the 1907 Tin Building, has been rebuilt, twice. After eight years of construction, the Tin Building reopen in the summer of 2022 as a culinary market and dining hall curated by chef Jean-Georges. This is the second resurrection of the Tin Building, as it was rebuilt before, in 1995 after a fire.

In 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission approved plans to relocate the building, moving it thirty-three feet away from its original spot. Hamilton Grange, the former home of founding father Alexander Hamilton, is the only other building the Landmarks Preservation Commission has allowed to be moved. Ninety-two pieces of the original structure, which was made of wood and corrugated sheet metal, were used in the SHoP Architects-designed replica, which is made of mostly new materials. The building will also be raised six feet to prevent it from flooding.

The oyster industry was a huge part of the Fulton Fish Market. Tourists and locals alike would flock to the market’s many restaurants and oyster stalls to consume the inexpensive bivalves. They were eaten raw, in a stew, or as “Fulton Market Roast,” “nine large oysters cooked in the shell, buttered and sprinkled with pepper.”

One of the most popular oyster restaurants in the market was Dorlon and Shaffer. Rees cites an 1866 guide that claims that the restaurant saw three to four hundred female customers a day and employed thirty men to serve its largely female clientele. Though oysters could be procured at many places around Manhattan, Fulton Fish Market vendors sold the most oysters than anywhere else by 1872.

Throughout the history of the Fulton Fish Market, changing technologies and advancements in refrigeration helped fish sellers expand their business. Better preservation and refrigeration methods helped sellers acquire different varieties of fish from places further and further away from New York City. They could send the fish further as well. Ice start to be heavily used at the market in 1846. Before this, the market largely served locals and fish were always live. With the increasing availability and affordability of ice, along with the nation’s growing railroad network, Fulton Market fish sellers could send their fish to other cities.

Being able to source fish from far away meant that the Market’s sellers were able to introduce New Yorkers to fish they had never tried before. Some of the seafood that the market made popular in New York City included sea scallops, pompano, grouper, and red snapper. Red snapper, which came from the Gulf of Mexico, was introduced to the Market by Eugene Blackford in he 1870s. Today, you can order akk kinds of fresh fish from the Fulton Fish Market online.

In 1892, Former New York Governor Alfred E. Smith worked at the Fulton Market and famously carried his experience there throughout his political career. Smith was sent to work at the Fulton Fish Market after the death of his father when Smith was just 14 years old. Starting in 1892, Smith worked as an assistant bookkeeper at Feeney & Co. Though assistant bookkeeper was his official title, he did many tasks throughout the market, including packing fish, and he started his day at 4am with the rest of the workers.

Smith would later say he was the only person in the New York State Assembly “who can talk the fish language,” and joked that his “cum laude” came from “F. F. M.,” the Fulton Fish Market, since his formal schooling was cut short by his father’s death. This working-class experience endeared him to voters who elected him to four terms as New York Governor.

If you want to get the best selection of fish, you need to get up early. The market is only open from 2am until 7am, Monday through Friday. It is closed on the weekends. Usually, the first customers to arrive are buying fresh seafood for New York City’s restaurants. It’s suggested to arrive by 5am for the best selection!

The market is refrigerated and kept at 38-40°F so be sure to bundle up. It’s also advised to wear boots. There is a small entrance fee.

On January 5th, join Untapped New York Insiders and the author of The Fulton Fish Market: A History, Jonathan Rees, for a virtual talk on the history of the Fulton Fish Market! This event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. If you’re not an Insider yet, become a member today (and use the code JOINUS to get one month free).

Next, check out A Look Inside the Fulton Fish Market, NYC’s Bustling Seafood Distribution Center

Subscribe to our newsletter