Name a Rat (or Roach) After Your Ex (or Lover) for Valentine's Day

Need ideas for a Valentine's Day gift? This one is sure to surprise!

New York City’s Fifth Avenue in Manhattan has been associated with glamour and wealth since the 1800s. However, when this now-iconic street was first laid out, it was given a rather humdrum name, Middle Road. The undeveloped parcel of land Middle Road cut through, which was sold in 1785 to raise municipal funds for the newly established nation, would become the epicenter of New York City’s high society. As the 18th century turned into the 19th century and the Gilded Age began, the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan renamed Middle Road Fifth Avenue.

Development of the city moved northward, led by millionaires who built palatial homes on the largely empty swaths of land. The string of fabulous Gilded Age mansions along 5th Avenue that stretched from 59th to 78th Street was dubbed the “Gold Coast,” and “Millionaire’s Row.” While many of the grandiose 5th Avenue mansions of New York City’s 19th and early 20th-century millionaires have been lost to time, there are some that remain intact today, serving as homes for non-profits, museums, and cultural organizations. Here, we revisit Gilded Age mansions of 5th Avenue, both past and present:

Admire the extant facades of Millionaire's Row and see stunning images of the opulent homes that have been lost while hearing about the scandalous goings-on inside.

Richard Morris Hunt, the architect commissioned to design a home for William K. Vanderbilt and his ambitious wife Alva, “knew his new young clients very well,” writes Arthur T. Vanderbilt II in Fortune’s Children, “and he understood the function of architecture as a reflection of ambition. He sensed that Alva wasn’t interested in another home. She wanted a weapon: a house she could use as a battering ram to crash through the gates of society.” Alva’s home needed to stand out against all the other Gilded Age mansions. Alva crashed through the gates of society in the Spring of 1883 with her “Fancy Dress Ball.” Until that groundbreaking ball, Alva, part of the new money rich, was not welcomed into the established New York City social scene ruled by Mrs. Astor.

Besting Mrs. Astor’s 400, Alva invited 1,200 of New York’s finest to her ball. Mrs. Astor was conspicuously left off the guest list, until she came calling at Alva’s door, symbolically bowing to the new order as she sought an invitation for her and her daughter. Inside Alva’s home, guests were greeted in a hall built of stone quarried from Caen, France. The interiors were decorated from trips to Europe, with items from both antique shops and from “pillaging the ancient homes of impoverished nobility.” The Vanderbilts affectionately referred to their mansion as the Petit Chateau. Sadly, the mansion was demolished in 1926 after being sold to a real estate developer and in its stead rose 666 Fifth Avenue, an office tower.

The Astor family started the trend of building 5th Avenue Gilded Age mansions uptown. The first popped up on a parcel of land at 34th Street and 5th Avenue. The land was a wedding gift to William Backhouse Astor Jr. and his new wife, Caroline Astor (née Webster Schermerhorn), from William Backhouse Aster Sr. in 1854. The house the couple had built on the property was a surprisingly modest four-bay brownstone, which was a stark contrast to the ornate A.T. Stewart mansion built across the street.

After William Backhouse Sr. died, Caroline became the reigning Mrs. Astor. In anticipation of increased entertaining duties, she made extensive renovations to the interior of their “humble” home. First, she transformed the Georgian drawing-room into a French Rococo style. The Astor family portrait was painted in the Rococo room. A new ballroom wing was added to the house, replacing the stables. In this ballroom, Caroline sat perched on a red silk divan, her “throne” as it would come to be known, and made or broke the dreams of New York City’s social climbers. Mrs. Astor’s ballroom famously held 400 guests, and to be one of “the 400,” meant you had made it into the highest echelon of New York City society. The Empire State Building now stands at the site of the Astor’s brownstone.

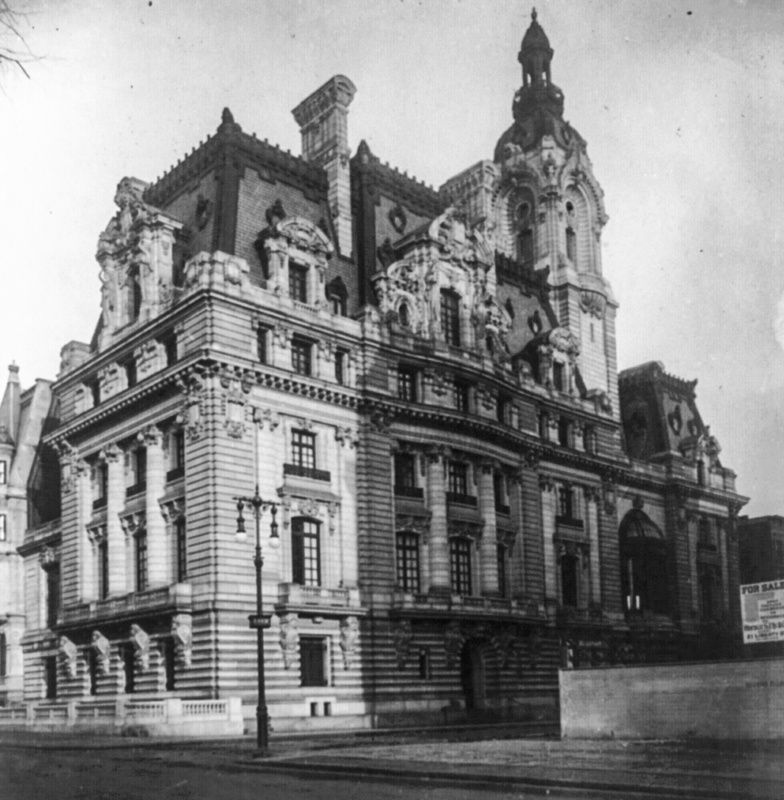

“Copper King” William A. Clark’s mansion at 960 Fifth Avenue was dubbed “Clark’s Folly.” The hulking home cost $6 million to build at the time, a sum that roughly equals $150 million dollars in modern times according to the Museum of the City of New York. Clark’s mansion, which took fourteen years to build, consisted of “121 rooms, 31 baths, four art galleries, a swimming pool, concealed garage, and underground rail line to bring in heating coal was completed in 1911.”

To facilitate the construction of the extravagant home, Clark bought a quarry in New Hampshire where he sourced stone and transported it to New York via a railroad he built specifically for that purpose. He also acquired a bronze foundry to make all of the metal fittings. Marble was imported from Italy, oak brought in from the Sherwood Forrest of England, and pieces of a French Chateau shipped over from France. After all of the work on the mansion was complete, Clark had a mere fourteen years to enjoy it before he passed away in 1925. The home became a white elephant. It eventually sold in 1927 for less than $3 million dollars and was promptly demolished, making it one of the most short-lived buildings in New York City. The mansion was replaced by a 12-story luxury condo building designed by Rosario Candela.

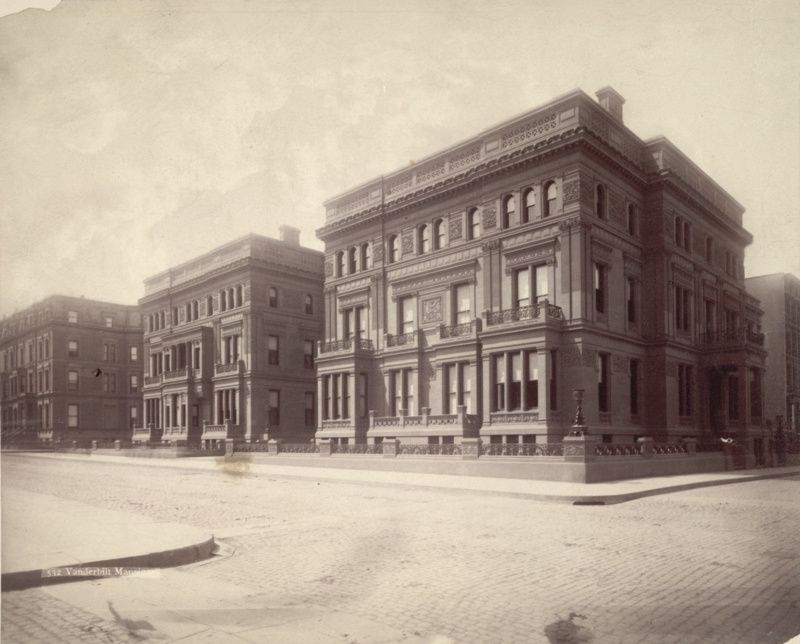

Two granddaughters of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt were each given their own 5th Avenue mansions. In 1882, the girls’ father, William Henry Vanderbilt, bought an entire block between 51st and 52nd Street where he built the “Triple Palaces,” three near-identical brownstone homes for himself and his wife along with their two daughters, Emily and Margaret. When hosting large events, the separate drawing rooms could be converted into one large ballroom!

The “palaces” caught the eye of another wealthy New Yorker, Henry Clay Frick. Frick is reported to have said, “That is all I shall ever want” on a drive past the Triple Palaces with his friend Andrew Mellon. In 1905, Frick would get the chance to have his own palace when he rented one out on a 10-year lease while George Vanderbilt was preoccupied with building the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina. He would have bought the house if William H. Vanderbilt’s will had not barred George from selling the home and art outside of the family. Later, via a loophole, the property and artwork were able to be sold by Vanderbilt’s grandson to the Astors, who in turn sold the holdings in the 1940s. Today, skyscrapers stand in place of the palaces and where once there were ballrooms and drawing rooms, there are now retailers like H&M, Godiva and Juicy Couture.

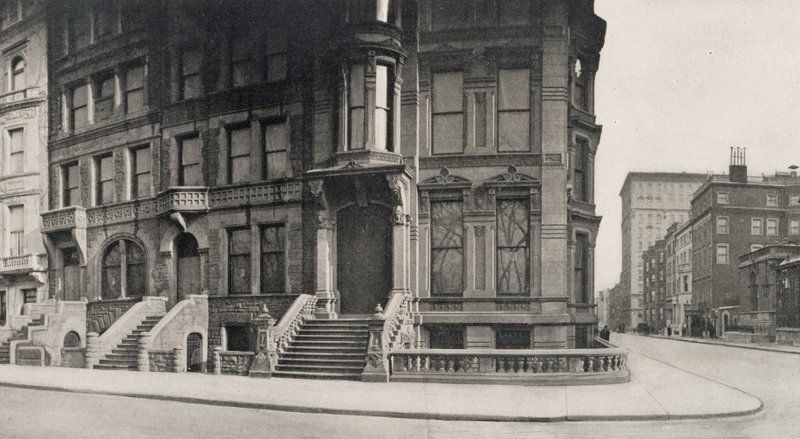

William Henry Vanderbilt’s other two daughters, Florence Adele Vanderbilt Twombly and Eliza Osgood Vanderbilt Webb, also got their own Gilded Age mansions on Fifth Avenue. In fact, there were so many Vanderbilt mansions built along Fifth Avenue, that a stretch of the street became known as “Vanderbilt Row.” Florence and Eliza’s townhouses were designed by architect John B. Snook in 1883. The two neighboring homes were very different than their sisters’ “Triple Palaces.” Florence and Eliza’s mansions boasted rusticated stonework, turrets, bow windows, and a mixture of domes and galbes that resulted in busy rooflines.

Florence lived at 684 Fifth Avenue until 1926 when she upgraded to a new mansion further north along Central Park. The Webbs sold 680 to John D. Rockefeller in 1913. Both were demolished for a skyscraper that has The Gap as its anchor tenant.

When John Jacob Astor began to build the St. Regis Hotel on Fifth Avenue in 1901, the wealthy residents in the area started to buy up land to prevent future commercial development. On the corner of 52nd Street and Fifth Avenue, Morgan Freeman Plant, son of the railroad tycoon Henry B. Plant, commissioned architect C.P.H. Gilbert to build him a large stone mansion. The mansion was later allegedly traded to Cartier in a legendarily bad deal that involved a string of pearls Mrs. Plant was particularly smitten with.

George W. Vanderbilt snapped up the land next door and built his “Marble Twins.” Designed by designed by Hunt & Hunt and completed in 1905, the homes, along with Plant’s mansion, were described by the AIA Guide to New York City as “free interpretation[s] of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century palazzi.” The Vanderbilt mansion at 645 was demolished but 647 remains.

The home of Cornelius Vanderbilt II was allegedly the largest single-family house in New York City at the time, a far cry from his father’s humble beginning on Staten Island. Using the fortune he inherited from his father the Commodore, Cornelius purchased three brownstones on the corner of 57th Street and 5th Avenue, only to knock them down and build his own from scratch. Not to be outdone by her sister-in-law Alva, Cornelius’ wife Alice Vanderbilt made sure their home was lavish. The Cornelius Vanderbilts hired George B. Post to design the home and later enlisted Alva’s favorite architect Richard Morris Hunt to help Post make the mansion even larger in the 1890s.

By the 1920s, the grand home was dwarfed by surrounding commercial developments including the Plaza Hotel and the Heckscher Building. Alice sold the home in 1926 to a realty corporation that demolished it and built the Bergdorf Goodman department store, which still stands there today. Despite the home’s demolition, you can still track down the remnants of the mansion scattered around Manhattan, including the front gates that are now in Central Park, sculptural reliefs now in the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, and a grand fireplace now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As a founding partner and treasurer of Standard Oil, Jabez A. Bostwick was one of the many men who made it big in the oil business. Bostwick, like most wealthy men of his time, took his fortune and his family to Fifth Avenue where he built a 10-room French Second Empire mansion in 1876 on the corner of 61st Street. When his daughter Nellie married, he extended the mansion to 801 and 802 Fifth Avenue.

After Jabez’s death and other family tragedies befell the Bostwicks, his wife Helen remained in the home until she too passed away in 1920. Family friend Mrs. Marcellus Hartley Dodge, a daughter of William Rockefeller purchased the Helen Bostwick home in 1922 and left it seemingly abandoned until 1977. In 1979, the Gilded Age mansions were demolished to make way for a 33-story luxury apartment building.

When Caroline Astor’s nephew William Astor knocked down his own townhouse to build the original Waldorf Hotel, right next door to her own mansion, she up and left. In 1894, Caroline and her son headed uptown to a more fashionable spot on 65th Street and Fifth Avenue. “Starchitect” Richard Morris Hunt, the same man who designed other Gilded Age mansions like William K. and Alva Vanderbilt’s Petit Chateau, was hired to design Caroline’s new abode. While the exterior appeared to be that of one large mansion, the interior was actually split into two separate living spaces, one for Caroline, and one for her son John Jacob Astor. The two residences were connected by a ballroom that could hold 1,200 guests (the same amount of guests that Alva Vanderbilt had invited to her fancy dress ball).

Admire the extant facades of Millionaire's Row and see stunning images of the opulent homes that have been lost while hearing about the scandalous goings-on inside.

After Caroline’s death, John Jacob Astor took over his mother’s portion of the mansion and made some major renovations. Unfortunately, he wouldn’t live long enough to enjoy the new space. After honeymooning in Europe with his new second wife, he booked a return trip aboard the doomed RMS Titanic. John did not survive the tragedy. While his new wife and her maid did make it safely back to New York City, they were forced to give up the mansion, as dictated by Astor’s will. It passed to Astor’s son from his first marriage, William Vincent Astor. Preferring his estate out on Long Island, William sold the 65th Street property to developers and auctioned off the interiors. Today the Temple Emanu-El stands in its place.

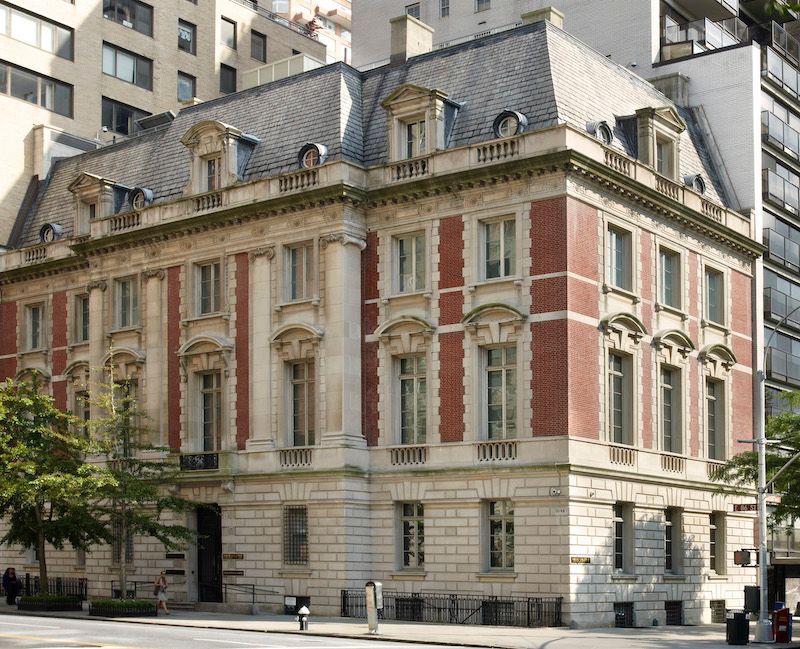

Warren & Wetmore, the architects of Grand Central Terminal and the Yonkers Train Station, designed the Fifth Avenue home of politician R. Livingston Beekman. Beekman had knocked down the 1867 home of Wallace C. Andrew at the site to make way for his creation. Beekman’s house differed from the rest of the Gilded Age 5th Avenue mansions with its comparatively diminutive scale. The defining feature of Warren and Wetmore’s scaled-down Beaux-Arts design is the two-story mansard roof. The Landmarks Commission, which designated the building in 1969, writes effusively that “in its noble scale this house if multiplied, could form a palace. The design has a purity of style which was executed with such finesse and authority that it sets this French-style residence apart as one of the finest small townhouses extant on Fifth Avenue.”

The Beekmans spent most of their time away from Fifth Avenue at their residence in Newport, Rhode Island. Beekman would eventually become the governor of that state. As the years rolled along, development seemed to literally squeeze the Beekman house, which is now sandwiched between two large apartment buildings. In 1946, the home was converted into the Mission of Yugoslavia to the United Nations. As a result, the building has been under attack multiple times for political reasons. In 1975, a bomb shattered the windows in the building, and in 1977, three armed men barricaded themselves inside.

Today, we know the Henry Clay Frick House as the Frick Collection, a repository of old masters (and a hidden underground bowling alley!). Frick began to amass his art collection while staying at one of the Vanderbilt Triple Palaces. In 1912, he commissioned Thomas Hastings, of the firm Carrère and Hastings, to build his own mansion on 5th Avenue and 7oth Street. The illustrious firm of Carrère and Hastings designed the New York Public Library at Bryant Park.

Frick instructed Hastings to build him “a small house with plenty of light and air,” one that would be “simple, in good taste, and not ostentatious.” Despite what Frick may have said, he ended up with a palatial, 61-room home embellished with ancient symbolism and decorated inside with Rococo and Renaissance furniture and decorative arts, and of course, his collection of old masters. The Frick mansion recently had a starring role in the HBO Max television show The Undoing. While the mansion is under renovation, the priceless works of art have been moved for the first time in nearly 80 years, into the Met Breuer.

Though grand in scale, the Harkness House is subtle in its classical ornamentation, much like the Frick Mansion. Designed in an Italian Renaissance style for the son of Ohio businessman Stephen V. Harkness, the home has many features that set it apart from its neighbors. For one, there is no grand ballroom inside. Instead, the home is divided into smaller intimate rooms. Take a peek inside here!

The modesty of the home is deliberate, even its name, which uses “House” instead of “Mansion.” The decoration that does adorn the house, however, holds meaning. The ornate fence which surrounds the property is said to be modeled after the fence which rings the Verona Scaligeri Tombs in Italy, a group of five Gothic funerary monuments that honor the Scaligeri family, who ruled in Verona in the 13th and 14th centuries.

The bowed front building between 78th and 79th Streets was, like so many 5th Avenue mansions, a wedding gift from Colonel Oliver Hazard Payne to his nephew Payne Whitney and Whitney’s new wife Helene Hay. Designed by noted architect Stanford White of the firm McKim, Mead and White, the home now serves as the Cultural Services of the French Embassy. Inside, you can see the stunning Marble Room, Reception Room and Venetian Room when you visit the hidden bookstore upstairs, Albertine. The Payne Whitney Mansion frequently appears in television shows like Law and Order and The Blacklist.

In the 1990s, it was discovered that the marble statue which adorns the mansion’s entryway fountain may be the work of Michelangelo. For decades, the sculpture stood in the center of the room while thousands of people passed by. Another treasure at the Payne Whitney mansion is a dress worn by Marilyn Monroe. It’s unclear how the dress got there, but there are photos of her wearing it! This is the last stop on Untapped New York’s Gilded Age Mansions Tour where you can go inside to the hidden bookshop.

Completed in 1899, The Fletcher-Sinclair Mansion is a French Gothic stunner on the south side of 79th Street and 5th Avenue. C.P.H. Gilbert was commissioned to design the home for banker Isaac D. Fletcher. When Fletcher died, he bequeathed the home and all of his art inside to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1918, it was purchased by oil tycoon Harry F. Sinclair.

In 1930, the home switched hands again. This time, it was sold to August Van Horne Stuyvesant Jr., a descendant of Peter Stuyvesant. After Stuyvesant Jr.’s death, the mansion was converted for the purpose its serves today, as the Ukrainian Institute of America. This non-profit organization, founded in 1948 by inventor, industrialist, and philanthropist William Dzus, is “dedicated to promoting the art, music and literature of Ukraine and the Ukrainian diaspora.” You can visit the mansion to see an art exhibition, and while you’re there, see the stunningly restored 19th-century rooms.

Clothing manufacturer Isaac Vail Brokaw’s home on the north side of 79th Street, like the Fletcher-Sinclair Mansion and Vanderbilt’s Petit Chateau, was inspired by the 16-th century Château de Chenonceau in France’s Loire Valley. Designed by Rose and Stone in 1887-1890, the mansion played an important role in the formation of New York City’s landmark laws.

Upon the deaths of Issac and his wife, the mansion went to their son George. After George died, it was bought by The Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) in 1946. Later, the IRE purchased two more of Brokaw’s houses and used them for office space. The next owner, the Campagna Construction Corporation, demolished the buildings in 1965. The Brokaw Mansions were designated as landmarks by the New York City Landmarks Commission in September 23, 1962, just a few months after the group formed. However, without the legislative backing the commission would receive in 1965, the designation was largely symbolic. When news of the demolition broke in 1964, it spurred preservationists into action. Though the 5th Avenue Gilded Age mansions were not saved, the passionate reaction to their demolition helped push forward landmarks legislation.

991 Fifth Avenue was originally commissioned by Mary Augusta King, daughter of former New York Governor John A. King. King hired architects James R. Turner and William. G. Killian to design the bowed front brick and limestone structure. It was completed in 1901. Upon Mary’s death, just four short years after the mansion was complete, it was purchased by banker David Crawford Clark, according to the Daytonian in Manhattan.

Clark hired Ogden Codman, Jr. to renovate the interior spaces. The American Irish Historical Society purchased the building for just $145,000 in 1939 and has remained there ever since. In 2021, the building was put up for sale for $52 million. When news of the sale broke, there was an outcry in the Irish American community. Even the Irish government opposed the sale. Now, the mansion has been taken off the market as a new interim board has control of the Society and the Irish government is putting up funds to help save the mansion.

Across the street from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1014 Fifth Avenue is a remnant of the last days of the Gilded Age. Built as one half of a pair in 1906-1907, the Beaux-Arts structure was created by real estate developer brothers William and Thomas Hall. They hired the architectural firm of Welch, Smith & Provot to design the buildings.

These Gilded Age mansions were filled with the most modern amenities, including some of the first Otis elevators in New York City and plumbing and heating systems. After serving as a private residence, 1014 Fifth Ave was purchased by the Federal Republic of Germany. In 1961 it became Goethe House, a center for German culture. At Goethe House. there were plays, exhibitions, and other cultural events. In 2008, the mansion was deemed unsafe as a public space and was abandoned for nearly a decade.

The mansion of Gilded Age industrialist William Starr Miller II and his wife Edith Caroline Warren was designed by Carrère & Hastings. The design was inspired by Place des Vosges, a 17th-century palace in Paris, France. The French style carries into the interior of the home as well where Edith’s bedroom is decorated in the Louis XVI style. After Edith’s died, Grace Vanderbilt, wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt III, bought the home.

The former mansion sits on the stretch of Fifth Avenue now known as Museum Mile. No longer a private residence, the mansion is home to the Neue Galerie, an art museum with a focus on German and Austrian art.

The Fifth Avenue home of steel magnate Andrew Carnegie was one of the later Gilded Age mansions to be built in New York City, completed in 1902. The grand home on East 91st Street was purposely placed further north on Fifth Avenue, away from the concentration of Gilded Age elite on “Millionaires Row.” The Carnegie Mansion was designed by Babb, Cook & Willard in an English Georgian style. Carnegie spent much of his later life here, working from an office where he managed his many philanthropic endeavors. The mansion is now home to the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Admire the extant facades of Millionaire's Row and see stunning images of the opulent homes that have been lost while hearing about the scandalous goings-on inside.

Next, read about the Top 10 Secrets of Grand Central Terminal

Subscribe to our newsletter