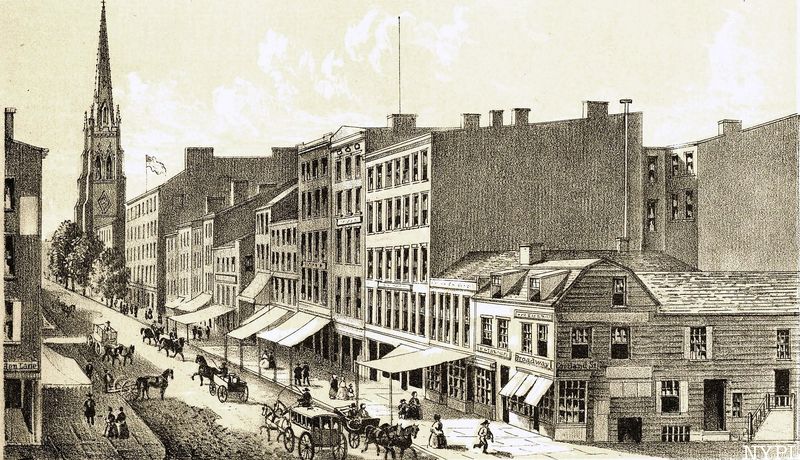

The early omnibuses of New York City “were little more than glorified stagecoaches,” writes author Jerry Mikorenda in his book America’s First Freedom Rider: Elizabeth Jennings, Chester A. Arthur, and the Early Fight for Civil Rights. “They were heavy, cumbersome vehicles whose wheels mired in mud or broke in holes” he continues.

In the early days of New York City’s public transportation, riding mass transit was treacherous. It was in these early days, on a hot July afternoon in 1854, that Elizabeth Jennings would make history. A school teacher who grew up in the Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan, Jennings would cross paths with future president Chester A. Arthur and become part of a groundbreaking court case that helped to desegregate New York City’s public transit. Here, we revisit the early days of New York City’s mass transit and Jennings’ historic ride.

The story of the public omnibus starts in 17th-century France. In 1662, inventor, philosopher, and mathematician Blaise Pascal created a transit system with seven horse-drawn voitures, or carriages. These public vehicles later came to be known as omnibuses from the Latin Phrase Justitia Omnibus, meaning “justice for all.” These carriages took six to eight passengers, usually members of France’s nobility, along a series of regular routes. While Pascal’s routes would outlive him by several years, the nobility eventually lost interest. It wasn’t until the early nineteenth century that his idea for public transit would be revived in other cities of the world, including London, New York, Paris, and Boston.

Mikorenda writes in his book that the early omnibus carriages in New York City “carried between twelve to twenty-eight passengers, with more people piled on the roof or hanging off the back.” The slow-moving buses were pulled by four horses and only reached a maximum speed of four miles an hour. “Steps up into the car were high and hard to get to and the seats unforgiving,” Mikorenda writes. Plus, the open-air carriages were unheated.

The roads proved no less treacherous than the confines of the vehicle itself. Mikorenda explains, “There were no traffic signals or road instructions. Buggies, wagons, pedestrians, and livestock all headed in their own direction at their own speed. Everything merged in a beehive of crawling, wiggling transportation on narrow city streets.”

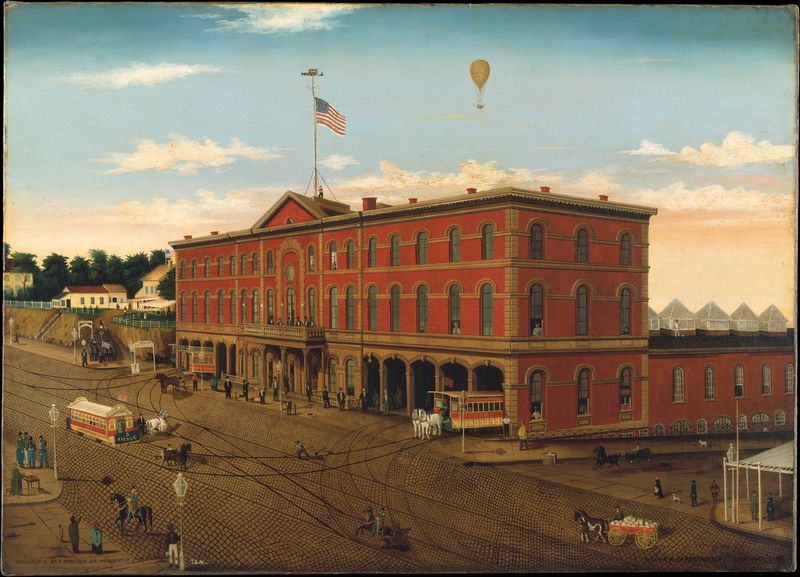

New York City’s public transit system of omnibuses recieved a major upgrade when streetcars were introduced in the 1832. John Stephenson, an Irish immigrant who apprenticed in a carriage repair shops, opened his own carriage producing workshop and got his big break when the New York and Harlem Railroad Company was granted the first streetcar charter in the United States for a new route from Prince to Fourteenth Street. It was to be the “first railway in the country to use horse-drawn cars on iron tracks.” The tracks allowed for a much smoother and efficient ride over the cumbersome and rickety omnibuses that roamed the streets.

Stephenson designed a brand new horsecar for the route. Mikorenda writes that Stephenson’s new design “consisted of three separate compartments seating ten passengers each. He then dropped the vehicle’s floor between the wheels and added elliptical springs to improve riding comfort.” The carriages were aesthetically pleasing and more comfortable thanks to cushioned seats, glass windows, and stove pipe heating. Stephenson named the prototype John Mason, after the President of the New York and Harlem Railroad Company.

Soon, Stephenson’s streetcars were all over New York City. In 1845 his business took up sixteen city lots on Twenty-Seventh Street and Fourth Avenue (now Park). He continually made upgrades and improvements to his cars such as adding a bell for passengers to signal their stop, and rearview mirrors for safety. Safety was a major concern for riders on the streetcars, pedestrians, and people in other vehicles. Collisions were commonplace as all types of different vehicles “tried to jump on the tracks and take advantage of the smoother ride.”

The streetcar tracks greatly impacted the areas through which they ran. Residents often complained of traffic and other associated hazards. Despite the many drawbacks of New York City’s early public transit systems, they continued to grow and expand with the growing city. In his book, Mikorenda notes that by 1854, when Jennings set out on her history making voyage, 683 coaches carrying 120,000 passengers drove through the city daily, making about 13,400 across Manhattan. There were 27 routes different routes including along Third, Fourth, Sixth and Eighth Avenues. Freewheeling coaches and omnibuses continued to roam the rest of the city as streetcar lines snaked along major thoroughfares.

At this time in New York City’s history, public transportation wasn’t really open to all members of the public. While members of different classes and ethnicities mixed on public vehicles, Black New Yorkers were banned by all transit companies from riding with white customers. Some companies ran “colored-only” cars. On July 16th, 195, Elizabeth jennings was in a rush to get to the First Colored American Congregational Church where she was the organist and choir leader. She didn’t have time to wait for the colored-only car.

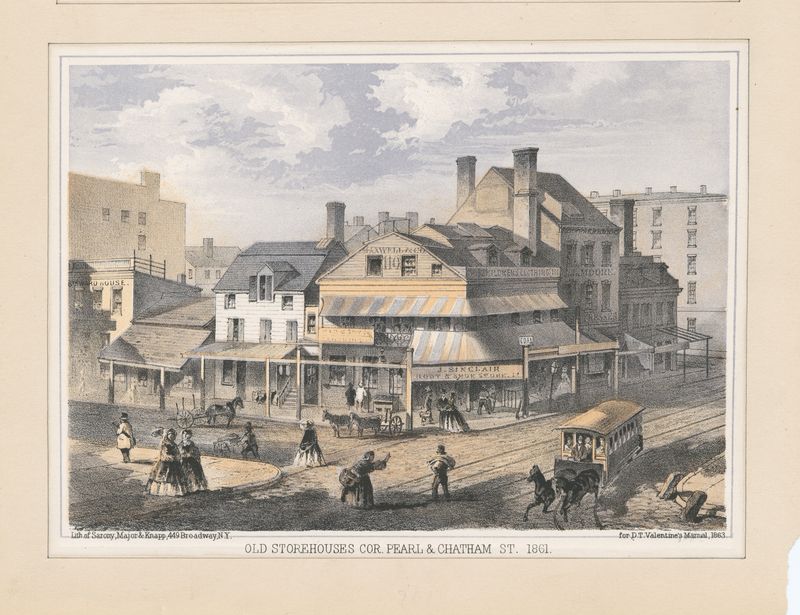

Rushing from her home at 167 Church Street to the bus stop on the corner of Chatham Street with her friend Sarah Adams, Elizabeth was relieved to see a streetcar waiting. When she approached however, she saw it was half-full of white passengers. The conductor said she’d have to wait for the car with “her people” that was expected shortly. Late to her destination and bothered by the inconvenience, Elizabeth refused to leave the platform until the “colored” car arrived. When it did, the conductor on that car told her it was full. She returned to the first car and demanded a ride.

The conductor relented and allowed Elizabeth and Sarah into the bus, but warned if any of the white passengers objected, they would have to leave. Elizabeth had had enough of the conductor’s treatment. She was a respectable person and demanded to be treated as such. The conductor, angered by Jennings standing up for herself, refused to let her sit and pushed her towards the door of the car. She was forcefully pushed out of the car, several feet down onto the street. Refusing to give in, she leapt back onto the stairs of the streetcar as the conductor gave orders to the driver to drive away.

The conductor flagged down a police officer and Elizabeth was frocibly removed from the car once more. After this incident, Elizabeth and her family would go on a crusade for equality on New York City’s public transit. Her father wrote a letter from his newly formed Legal Rights Association, “To The Citizens Of Color, Male And Female, Of The City And State Of New York,” to help raise funds for a legal suit. He hired the illustrious, and expesnive, law firm of Culver, Parker & Arthur. A young Chester Arthur was the firm’s junior member and he took on the case.

Elizabeth’s case was heard by the Second District of the New York State Supreme Court in Brooklyn on February 22, 1855. She won. In her bid for equal transportation rights, Jennings recieved a $225 settlement from the Third Avenue Railroad Company (down for her original claim of $500), and set off a chain-reaction of other companies allowing Black riders in all cars. Rather than deal with the cost of legal suits, one by one, other transit companies began to integrate. The New York State legislature officially outlawed discrimination on public transportation in the city with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1873.

Elizabeth Jennings now sits in the history books among other African American women who have been punished for simply trying to get to where they were going. Sojourner Truth had her shoulder blade broken when she attempted to board a “whites only” street car in D.C. Harriet Tubman was thrown into a New Jersey railroad baggage car. After Jennings, Rosa Parks, Claudette Colvin, and others continued to fight for equal transit rights by refusing to give up their seats.

Omnibuses and streetcars were the predominat mode of public transit well into the 20th-century. As technology advanced, the horse-drawn cars were steadily replaced by steam and electric powered trolleys. The subway opened in 1904 and streetcar service ended in New York City on April 6th, 1957.

Discover more about the life and times of Elizabeth Jennings in a virtual book talk with author Jerry Mikorenda! Available below or in our video archive for members at the Fan tier or higher.