Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Hudson Valley region of New York state is dotted with extravagant mansions of times gone by. Luckily, there are still many fine examples of this opulent architecture that still exist, but there are many luxurious estates that have been lost. Here, we revisit some of the most grand estates of the Hudson Valley and explore the stories of why these homes were forgotten.

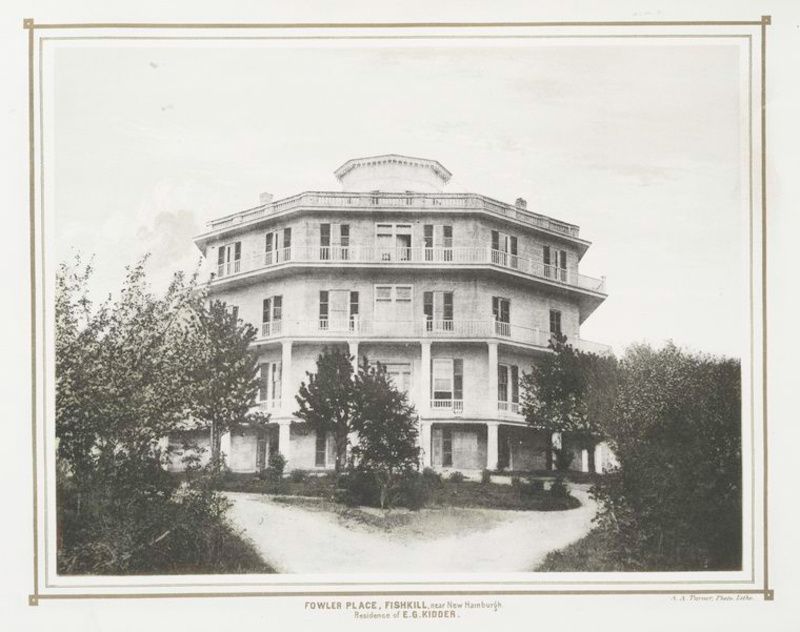

In the 19th century, octagon-shaped houses were all the rage. This quirky architectural trend is credited to Orson Squire Fowler. Fowler was a phrenologist, lecturer, architect, and editor who penned The Octagon House: A Home for All in 1853, a book that extolled the many health benefits of living in an octagon-shaped home. He argued that the shape allowed more natural air and light to flow through the home and that it had cooling and heating advantages as well.

Fowler built his own octagon house in Fishkill and it became an attraction that drew spectators from far and wide. The 8-side home boasted 60 rooms and sat on 130 acres of property. Amenities of the home included indoor plumbing, hot water furnaces, speaking tubes, and dumb waiters. In 1860, the home was purchased by saddlery merchant Edward Griffin Kidder for $18,000. After Griffin, the curious home had many different owners before being converted into a boarding house. It was condemned in 1897 and demolished. The Hudson Valley does still have an existing octagon house in the town of Irvington.

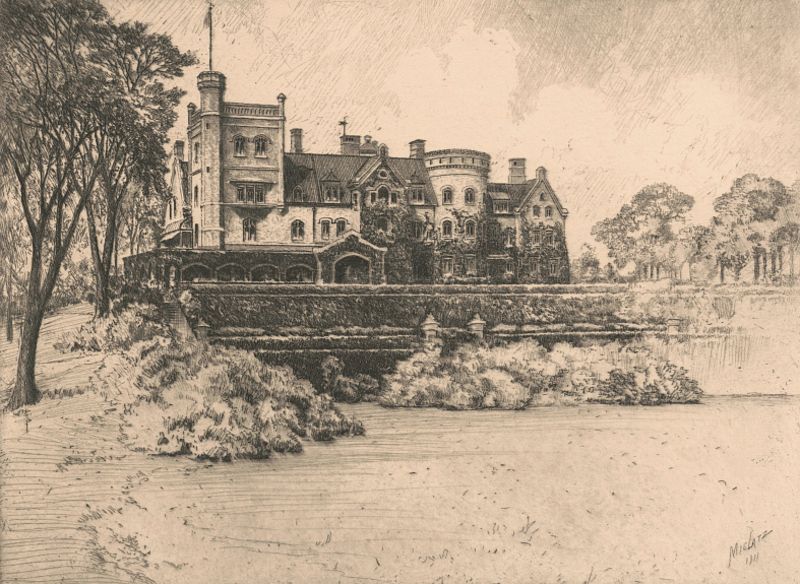

The original Rockwood Hall in Sleepy Hollow, New York was built by wealthy merchant Edwin Bartlett in 1848. Bartlett constructed a massive English Gothic-style castle made of locally quarried stone, complete with a turret, pointed arched windows, and parapet. In 1886, the property was acquired by William Rockefeller, brother of Standard Oil founder John D. Rockefeller, for $150,000. He quickly got to work making the estate as large and as luxurious as possible.

Rockefeller expanded the bucolic grounds of the estate from 200 to a whopping 1,000 acres. He expanded the castle as well. According to the New York State Parks Department, it’s unclear if Rockefeller renovated the existing structure or tore it down and started from scratch. Whatever his approach, the end result was a 204-room mansion that was surpassed in size only by Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina. Biltmore was the largest private dwelling in the United States and belonged to George Washington Vanderbilt II.

Rockefeller’s renovations were said to cost over $3 million. Features of the home included a fireplace in every bedroom, a music room, a library, and a conservatory. The grounds were landscaped by Frederick Law Olmsted, landscape architect of Prospect and Central Parks, and featured rare trees such as Golden Oaks, Weeping Beeches, and Pink Horsechestnut. Six miles of paved carriage roads snaked through the grounds. Outbuildings included “a three-story coach stable, a carpenters shop, a paint shop, a farm barn, a hennery, 17 greenhouses and a 4-acre outdoor nursery containing more than 1,000 rare and valuable trees and shrubs.” There was also a boathouse and private dock.

Rockefeller lived at the massive estate until his death in 1922. His heirs sold the mansion to a group of investors that created Rockwood Hall, Inc. The corporation converted the home into a country club with an 18-hole golf course, but it went bankrupt by 1936. John D. Rockefeller, Jr was able to acquire the estate in bankruptcy court. Having no use for the buildings on the property, he had them demolished from 1941 to 1942. He left the land to his son Laurance S. Rockefeller, who donated a large part of the property to New York State in 1999. Since then, the donated grounds have been part of the Rockefeller State Park Preserve which is open to the public. Rockefeller’s former carriage trails are now trails for walkers and hikers and the occasional horseback rider. Visible remnants of the main house’s foundation and a gatehouse on Route 9 can still be seen.

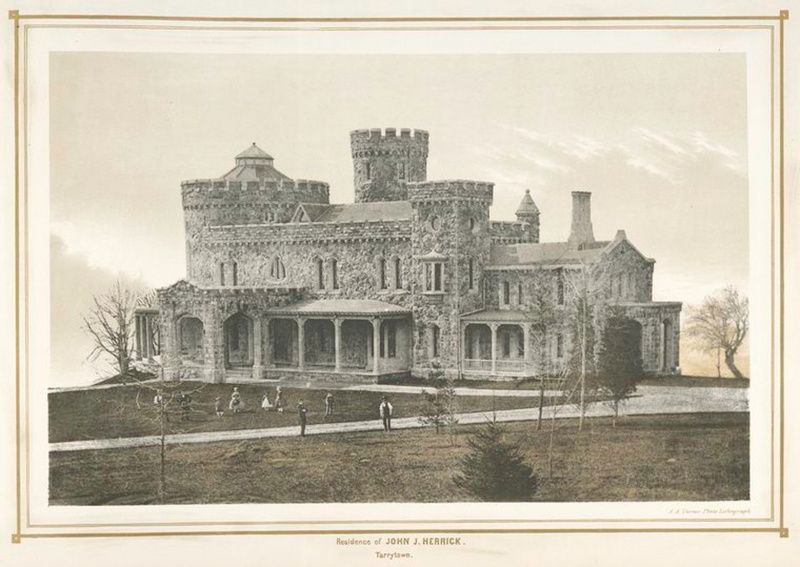

John J. Herrick’s castellated Gothic mansion designed by Alexander Jackson Davis looks like something straight out of a fairytale. It was designed in 1855, shortly after Davis completed another Tarrytown castle, Lyndhurst (which still stands today). Herrick, a dry-goods merchant, could enjoy stunning views of the Hudson River from the top of his three-story tower which faced west over the water.

Inside the granite castle – which was known as Ericstan and simply, The Castle – there were 30 rooms including a circle drawing room with a vaulted ceiling on the first floor of the tower. Herrick’s dining room table could easily seat 18 guests! Herrick wrote of his castle that it was the “best and most commanding building on the Hudson and the most beautiful and will stand through all time.” Sadly, Ericstan could not weather the test of time. Herrick’s dry-goods fortune dried up in 1865 and he was forced to sell the castle. From 1895 to 1933 it served as a private school for girls. When the school closed in the midst of the depression, no buyers could be found. The castle sat empty for over a decade before being demolished in 1944.

Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones commissioned the Norman-style mansion at Wyndcliffe. It was designed by George Veitch and built in 1853 in the Hudson Valley town of Rhinebeck. Originally an extravagant estate on 80 sprawling acres, the home has since become one of the region’s most famous ruins. It is believed that the phrase “keeping up with the Joneses” originates from the lavish lifestyle of Elizabeth and the attempts of her contemporaries to match it. Elizabeth’s mansion featured high arches and a three-floor central atrium topped with stained glass that was likely made by Tiffany.

One person who did not admire the mansion was Elizabeth’s niece, American novelist Edith Wharton. In recollections of her summers spent at Wyndcliffe, Wharton wrote, “I can still remember hating everything at Rhinecliff, which, as I saw, on rediscovering it some years later, was an expensive but dour specimen of Hudson River Gothic.” The Joneses sold the home to the Finck family who called it “Linden Grove” for the many Linden trees on the property. The Fincks were the last family to own the mansion for a significant period of time. It has been abandoned since the 1950s and since then has been steadily decaying and falling apart. A demolition permit requested by the owner in 2016 was approved but never acted upon, so there is still a glimmer of hope for this once-grand estate. As of December 2022, the current owners, brothers John and Mark Barboni, have submitted an application to the town for work that will stabilize the ruins.

Fans of the 1960s television series Dark Shadows might recognize this lost estate. The exterior served as the setting of “The Old House” in the series. In the series, the home was built in 1767 and was the mansion of the Collins family, the first Collinwood estate, until 1796. The nearby estate of Lyndhurst served as “the new house” or the new Collinswood in the 1970s Dark Shadows feature films.

In reality, this mansion was built much later, around 1850, for Moses Grinnell’s niece and her husband. The next owners, Russell Hopkins and his wife Vera Siegrist, called it The Colonnades and it was part of their larger estate named Veruselle. It was purchased in 1929 by stockbroker William R. Spratt. The final owner was Anna Gould, Duchess de Tallyrand. Gould was the daughter of railroad magnate Jay Gould and owner of the nearby Lyndhurst estate. The house sat vacant after she died in 1961. A fire destroyed the home in 1969 and only remnants of its foundation remain.

Chicago diamond merchant Sigmund Stern built the stone mansion, pool, and other buildings that once stood as the Northgate estate. Its other commonly known name, the Cornish Estate, comes from the second owners, Edward J. Cornish and his wife Selina. The Cornishes bought the 650-acre property in 1917. They enjoyed twenty years in the house before they both died in 1938, just two weeks apart. The estate was inherited by their nephew Joel who didn’t maintain it. In 1956, a fire destroyed the interiors and it was left in a state of ruin.

In the 1960s, the land was purchased by Central Hudson Gas and Electric with plans to build a power plant, but those were scrapped. Soon after, the property became part of Hudson Highlands State Park. Today, you can see the stone ruins of the mansion and remnants of various outbuildings on a hike through the woods.

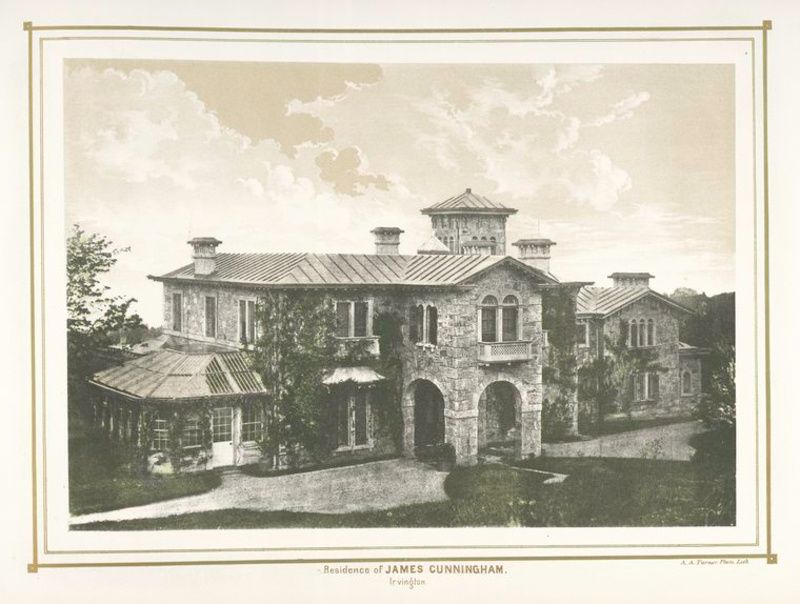

The stone mansion of Scottish-born steamboat magnate James Cunningham sat on eight acres of land in the town of Irvington, in close proximity to the grand estates of many other wealthy men of industry. The 18-room mansion you see in the image above featured in Villas on The Hudson: A Collection of Photo-Lithographs of Thirty-One Country Residences which was published in 1860, was actually the smaller of Cunningham’s two Irvington mansions, according to a report on the book. The New York Times described the mansion: “As seen from the river it presented a pleasing and dignified picture, standing well atop. a steep hillside, surrounded by broad lawns and long terraces, and flanked by spacious greenhouses and substantial barns.”

Cunningham’s large collection of art necessitated him to have two mansions instead of just one. Much of Cuningham’s collection was later donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He planned on retiring in the larger of the two homes but died while in residence in the smaller one. The mansion was passed on to his daughter Mary and her husband Herber R. Bishop. In 1878, the home and many priceless paintings inside were destroyed by a fire. Bishop was renovating the home at the time and had not yet had the chance to move in.

In the French Hill section of Donald J. Trump State Park, you’ll find various remnants leftover from the 550-acre estate of William Delavan Baldwin, a prominent member of the Otis Elevator Company. Known as French Hill Farm, The Yonkers Herald describes a “pretty,” “low rambling cottage” with a “flower-bordered flagged pathway” that “leads to the main door of the home.” Baldwin had homes in New York City, Greenwich, and Stamford, Connecticut before he purchased French Hill Farm in 1923. He would die at the estate of a sudden heart attack seven years later.

All of the structures on the property were torn down by 2016 including the main house, barns, swimming pool, and tennis court, though you can still see vestiges of them today. As you pass the entrance kiosk of Trump State Park, you come across the remnants of a stone wall. There are also wide stone steps and the floor of the tennis court. Random stone pavers peak through the grass.

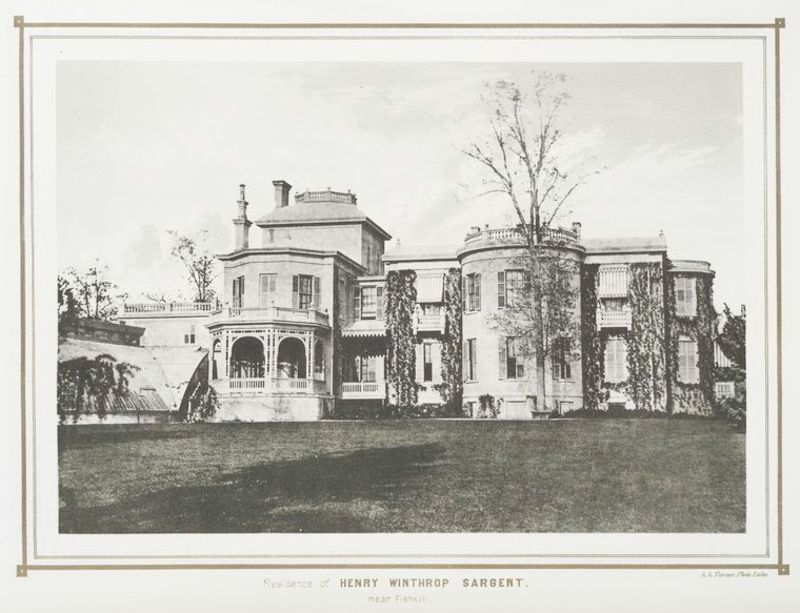

Henry Winthrop Sargent developed a passion for horticulture through caring for his estate in Fishkill Landing (now Beacon). At Wodenethe, as the 20-acre estate was called, he experimented with different garden layouts and sourced trees and plants from around the world. He frequently went on garden scouting trips to find inspiration. He wrote about his travels in “Skeleton Tours,” a guide to the gardens of the British Isles, the Scandinavian Peninsula, Russia, Poland, and Spain. He became fast friends with landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing.

After Sargent’s death in 1882, his son Winthrop took over the mansion and grounds. Later, the home passed to his niece. The niece ended up selling the estate to Dr. Clarence Slocum in 1921 for use as part of Craig House, the sanatorium that he ran. For decades, some of the patients of Craig House lived in the mansion while receiving treatment, In 1954, the Craig House was downsized and sold off the Wodenethe estate. After emptying the mansion, the structure was set ablaze in a controlled fire that destroyed it.

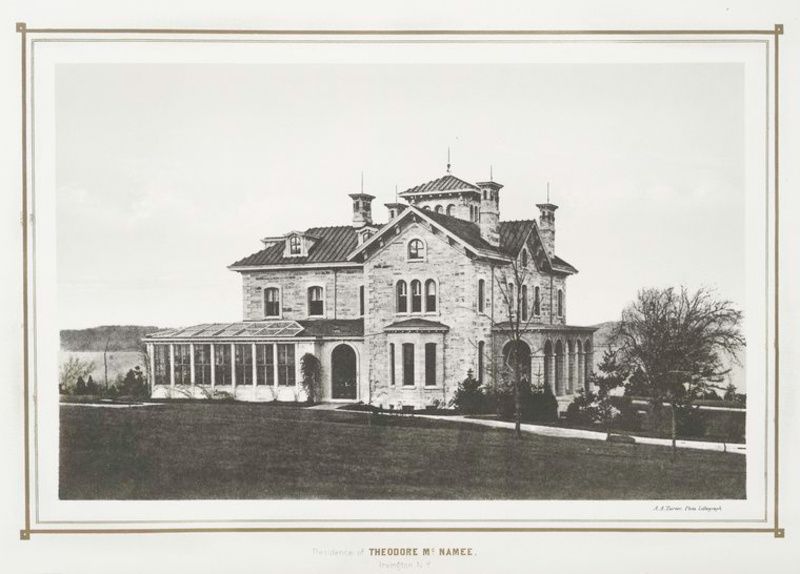

Theodore McNamee’s grand Hudson Valley mansion was the victim of real estate development in 1928. The land was sold and divided up in into 150 individual plots. Today, where McNamee’s mansion once stood is a residential area called Spiro Park.

McNamee was a principal at Bowne & McNamee, a leading New York City silk and dry goods exporter, in 1853 when he purchased his Irvington estate. It was called Rosedale. The architect is officially unknown but it has been speculated that Joseph Collins Wells designed the 18-room mansion. Wells had designed Bowne & McNamee’s silk warehouse in Manhattan.

Next, check out 13 Lost Mansions of the Gold Coast on Long Island

Subscribe to our newsletter