Vintage 1970s Photos Show Lost Sites of NYC's Lower East Side

A quest to find his grandmother's birthplace led Richard Marc Sakols on a mission to capture his changing neighborhood on film.

Whitestone, Queens has been home to a Soviet spy and famous American authors, it boasts a spaceship-shaped church, and has been the site of multiple shipwrecks. You might not have realized that all of this history is hidden within the quiet, residential neighborhood that sits east of College Point and west of Bayside. Inaccessible by subway, within Whitestone, you’ll find the smaller neighborhoods of Beechhurst and Malba, both of which were popular destinations for celebrities. The name, Whitestone – which the neighborhood shares with its eponymous bridge – was derived from the limestone that lay on the shore of the East River during the time of Dutch settlement. The area was mostly occupied by the estate of politician and merchant Francis Lewis, and by the mid-1800s, many mansions were constructed in the area. Development picked up around the early 1900s, and today, most restaurants and businesses are located along 150th Street and 14th Road. From its famous residents to its fascinating sights, uncover the top 10 secrets of Whitestone.

Whitestone Point has been the site of quite a few shipwrecks over the years, including the wreck of the Holland III. The Holland IIII was a prototype submarine manufactured by John Holland, whose Holland 1 was the first Royal Navy submarine. He also developed the first submarine that was formally commissioned by the U.S. Navy. It was modeled off his Fenian Ram, a much larger submarine that would be used against the British by the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish republican association in the U.S. The Brotherhood, though, stole the prototype and the Fenian Ram from the Morris Canal Basin after a money dispute. The group intended to use the ship to fight for Irish independence. After traversing the East River, the ship started to sink near Whitestone Point, sinking 110 feet. It has never been recovered, though recently the National Underwater and Marine Agency tried its hand at it.

The year 1908 was a particularly disastrous year for shipwrecks near Whitestone. Two occurred on the same day, May 22: the H.T. Hedges, a schooner, sunk off Whitestone Point, though all five people on board survived. The other ship was an unknown schooner that collided with an anchored barge off Whitestone and was later beached. Later that year on November 3, the Henry L. Walt caught fire off Whitestone Point. The ship was later beached at College Point, and all four people on board were saved.

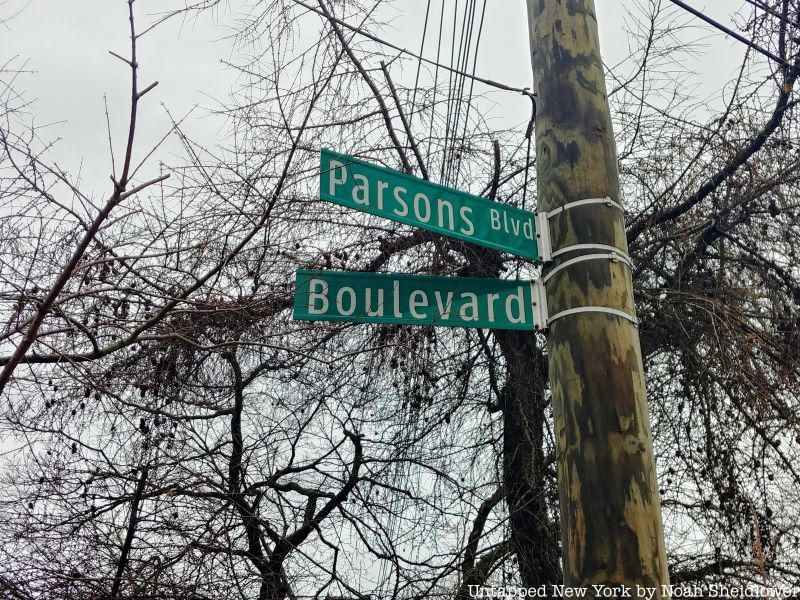

In the Malba neighborhood within Whitestone, there is a street simply named “Boulevard.” The small street to the east of Powell’s Cove Park and west of the Whitestone Expressway curves toward the waterfront, offering clear views of the Whitestone Bridge. The street is lined with expensive homes — Malba is considered one of Queens’ most expensive neighborhoods and boasted the most expensive home in the borough which was on the market for $8.8 million in 2017. Much of the waterfront stretch is owned by the Malba Association, making it private property.

Malba was an early planned community with winding streets and more of a suburban feeling than nearby College Point. Homes are detached with spacious lots, many built on what was once the Van Nostrand farm. First settled in 1908, Malba was named for its five developers: George Maycock, Samuel Avis, George Lewis, Nobel Bishop, and David Alling. This acronym actually predates many other famous New York City acronyms including Tribeca and SoHo.

St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church was founded in 1916 as one of Queens’ first Orthodox churches. For nearly five decades, from its opening in 1919 until its demolition in 1968, the church was housed in a wooden structure. The new structure built for the church was anything but orthodox; its design has earned it the unofficial nickname of “spaceship church.”

The church feels futuristic because of its exaggerated arches and curvy design, as well as its exterior silver tiles. The church, located at 14-65 Clintonville Ave, is also known for its blue onion dome. It has oval windows and a metallic barrel roof. The building was designed by architect Sergey Padyukov, who designed churches across the United States including a handful in New Jersey and one in Sitka, Alaska. In contrast to the striking exterior, the interior looks more standard, featuring Orthodox iconography and typical (though ornate) wooden pews.

The LIRR Whitestone Branch once connected Willets Point to Whitestone, running along Flushing Bay. The rail line was originally planned as part of the Flushing and North Side Railroad, though it later became a subsidiary of the Long Island City and Flushing Railroad. The branch opened in 1869 and was electrified in 1912, but just about a decade later, service started to decline. The line was abandoned in February 1932 after attempts to consolidate it with the New York City subway system, which were unsuccessful because of the cost of removing grade crossings.

Parts of the branch remained even after it was abandoned, including a small section leading to Corona Yard that was maintained up until the 1970s. There is even a portion east of the Mets-Willets Point station that remains today, though it is inaccessible. Additionally, a spur of the branch near the Flushing River was kept until 1983, when it was abandoned after going underwater; there has been no trace of the spur over the past few years. Though no tracks remain, there is a gate to the former Beechhurst Yacht Club that corresponds to the former northern terminus of the branch.

Beechhurst is a neighborhood of Whitestone bordered by the East River and the Cross Island Parkway. During the era of silent movies, Beechurst was a go-to location for famous stars including actress Mary Pickford, nicknamed “America’s Sweetheart” during the silent film era, as well as the Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields. Perhaps the neighborhood’s most notable resident was Arthur Hammerstein, the son of Oscar Hammerstein I of the Rogers and Hammerstein duo. Arthur Hammerstein produced operas for Rudolf Friml, led Broadway productions, and built what is today the Ed Sullivan Theater. Hammerstein was comedically arrested in 1920 for alcohol possession, even though it was just iced tea.

Hammerstein built a mansion in Beechhurst facing the Long Island Sound, where he lived with his wife Dorothy Dalton, a silent film actress. Their home, located at 168-11 Powells Cove Boulevard, is now a New York City designated landmark. It was designed by suburban and rural home architect Dwight James Baum and was named the “Wildflower” in honor of one of Hammerstein’s most successful Broadway productions. He sold the Neo-Tudor home in 1930 amid the Great Depression so he could sustain the Hammerstein Theater. The property was converted into the Clearview Yacht Club.

While DeWitt Clinton was governor of New York, Whitestone was known as Clintonville, since he had property in the neighborhood. This name was short-lived, especially after the discovery of a hot spring on 14th Street and Old Whitestone Avenue during the mid-1800s.

This hot spring gave Whitestone the name Iron Springs, attracting anemic patients from across the city and state who were looking to cure their iron deficiencies. A local doctor advocated for patients to drink the water to get plenty of extra iron. By 1920, the Water Department sank wells near the spring, but those wells were short-lived since the iron in the water ruined clothes.

Francis Lewis Park is one of Whitestone’s most scenic destinations, located right near the Whitestone Bridge. The park honors Francis Lewis, a merchant and representative from New York at the Continental Congress who signed the Declaration of Independence. Lewis was born in Wales but received his education in London before setting sail for New York around 1734. He created a successful trading company in New York City and Philadelphia, all the while making trips to places like Saint Petersburg and the coast of Africa. He married Elizabeth Annesley, and despite being imprisoned in France during the French and Indian War, moved to Whitestone where he used his wealth to build a mansion.

It wasn’t until 1774 that he officially started his political career. He began as a New York delegate to the Provincial Congress, then from 1775 to 1779 was a delegate to the Continental Congress. He was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, followed two years later by the Articles of Confederation. Despite his success in politics, his Whitestone home was destroyed and his wife was arrested by the British. His wife was eventually released in a prisoner trade, but she died shortly after due to the poor treatment she received while imprisoned. During the American Revolution, after he rebuilt his home, he served on the Secret Committee and the Marine Committee. He was also the Chairman of the Board of Admiralty. After the war, Lewis helped his son (who fought for the Continental Army) start his business, and he became a vestryman for Trinity Church.

More than perhaps most Queens neighborhoods, Whitestone has a significant amount of celebrities who have lived in the area. Charlie Chaplin was among the silent film stars who worked at the nearby Astoria Studios and his wife Paulette Goddard, was coincidentally raised in Whitestone. Rudolph Valentino, who starred in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, also had a home in Whitestone. Harry Houdini lived on Powells Cove Boulevard with a home near the water, which was demolished in 1995. Other notable residents included Whittaker Chambers, a writer, and Soviet spy; Harvey Samuel Firestone, who founded Firestone Tire and Rubber Company; actor and director Buster Keaton; and William Shea, a lawyer and founder of the Continental League whose name was given to Shea Stadium.

Another famous resident of Whitestone was Walt Whitman, who lived here in the early 1840s. In a letter, he wrote that Whitestone had pleasant scenery but not the most pleasant people. He wrote:

“I am quite happy here; and when I say this, may I flatter myself that some chord within you will throb ‘I am glad to hear that?’—Yes, as far perhaps as it falls to mortal lot, I enjoy happiness here. —Of course; I build now and then my castles in the air.—I plan out my little schemes for the future; and cogitate fancies; and occasionally there float forth like wreaths of smoke, and about as substantial, my day dreams.—But, take it all in all, I have reason to bless the breeze that wafted me to Whitestone.—We are close on the sound.—It is a beautiful thing to see the vessels, sometimes a hundred or more, all in sight at once, and moving so gracefully on the water.—Opposite to us there is a magnificent fortification under weigh.—We hear the busy clink of the hammers at morn and night, across the water; and sometimes take a sail over to inspect the works, for you know it belongs to [the] U.S.”

The Bronx-Whitestone Bridge was built in just 23 months, six months ahead of schedule. Construction on the bridge was rushed to coincide with the opening of the 1939 World’s Fair. Robert Moses, who was instrumental in bringing the fair to New York, convinced the city to have it at the Corona Ash Dump, which was filled with garbage and ashes from furnaces. The site was inaccessible from the rest of the city and Long Island, but Moses proposed converting the dump site into Flushing Meadows-Corona Park there.

After planning since June 1937, the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge opened on April 29, 1939. One day later, the World’s Fair opened, coinciding with the 150th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration. Thousands of cars used the bridge as a “gateway” to the fair. Perhaps to the surprise of the bridge’s designers, Robert Moses actually praised its design, even though it was structurally flawed. The bridge, which used to have pedestrian walkways (removed in 1943), was first proposed over three decades earlier in 1905 but was heavily delayed since Queens residents feared it would disrupt the area’s “rural” character.

Whitestone hosts a number of large companies, particularly along the Whitestone Expressway to the east of the New York Times printing plant in College Point. Perhaps the most famous is Glacéau, officially Energy Brands, which is a subsidiary of The Coca-Cola Company. Energy Brands manufactures and distributes enhanced water and sugary drinks including vitaminwater and smartwater. It is located at 1720 Whitestone Expressway, not far from the smaller company White Rock Beverages.

A perhaps unexpected company headquartered in Whitestone is the World Journal, the largest Chinese language newspaper in the U.S. with a circulation of about 350,000. It is published in major American cities including Los Angeles, Boston, Dallas, and Chicago. The Queens Tribune also had its headquarters in Whitestone before shutting down in 2019. Another famous company that was headquartered here but shut down in 1915 was Kinemacolor, the first successful color motion picture process that led to the growth of color films.

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of College Point!

Subscribe to our newsletter