Immerse Yourself in a Digital Garden at Artechouse NYC

Uncover an underground digital art space where spring is blooming!

Ghost signs — faded reminders of businesses that have long vanished — are hiding in plain sight across New York City. As many of New York’s oldest structures are Downtown, the city’s oldest ghost signs can be spotted there. But the buildings north of 14th Street also boast an impressive amount of faded ads. More than 100 are included in the new book Ghost Signs: Clues to Uptown New York’s Past. Here we highlight 10 of the best, plus one that requires an elevator ride to see.

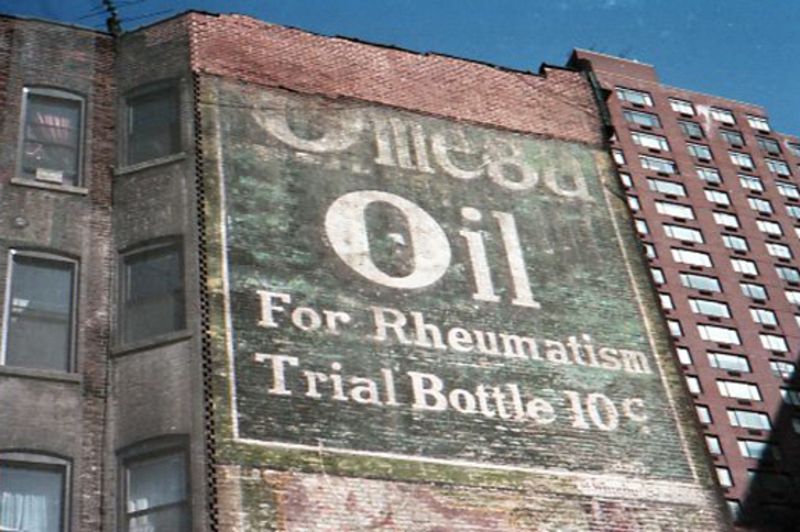

Three majestic ghost signs for Omega Oil survive within the West 147th–149th Streets Historic District of Harlem. Omega Oil was a liniment that promised to heal just about everything. A 1901 Brooklyn Daily Eagle ad described the wide range of ailments the oil would “cure”:

“Omega Oil cures Weak Backs. Lame Shoulders, Tired Arms and Legs. Stiff Elbows, Wrists, Fingers, Knees, Ankles and Joints. Rheumatism, Lumbago, Neuralgia, Sore Throat, Cold in the Chest, Sore Muscles. Aching, Itching, Sore, Swollen, Tired, Sweaty Feet.

A godsend to old people. Freshens, invigorates and strengthens the muscular tissues after hard exercise, hard work or hard pleasure. Good for everything a hard liniment ought to be good for.”

The Omega Chemical Company moved from Boston to 257 Broadway in New York in 1900. By 1908, its address was 576 Fifth Avenue. Omega Chemical operated a factory at 243 Greenwich Street from about 1904. The factory moved to Brooklyn in 1914.

Omega spent decades advertising its dubious curative properties in newspapers and on walls across the country. Two large Omega Oil signs were revealed during the construction of 150 Columbus Avenue in 1995. Omega pioneered the use of endorsements by professional athletes. A 1934 New York Daily News ad featured boxer John L. Sullivan, who states, “You can put me down as saying that Omega Oil is fine stuff to rub on the body and limbs. Its green color suits me, too.”

“The successful athlete doesn’t take chances with his physical condition,” another ad advised. “Every other man wants to be strong and vigorous too, no matter whether he is a laborer, a merchant, a professional man, or a preacher.” Omega Oil was acquired by Colgate-Palmolive-Peet in 1931. The brand disappeared sometime after 1957 when it was accused of false advertising by the Federal Trade Commission.

“The Lerner Shops — they are in every important neighborhood in New York and in all other Eastern cities — know the coming mode just a little ahead of most other shops,” read a 1922 ad in the New York Evening World. “To carry styles that are at all times in the forefront of fashion — to have them just a little sooner than everyone else — and to keep them always in the pink of freshness — that is the Lerner policy.”

Lerner Shops was founded in 1918 by Samuel A. Lerner and Harold M. Lane in New York City. From its start as blouse manufacturer, Lerner Shops became a popular chain of women’s wear stores. Eighteen more shops opened that year.

In 1928 Lerner moved to 478 Seventh Avenue in the expanding Garment District as millinery and apparel businesses migrated uptown from Broadway below Houston Street. Daytonian in Manhattan explains that bail bondsmen, then an unsavory occupation, moved into the former residential building. A restaurant on the second floor serving liquor was raided by Federal prohibition officers in December 1926.

Lerner Shops renovated the building and opened a retail store on the ground floor. The front of the building was redesigned with a medieval theme that includes stone heads across the parapet. Exquisite coats of arms are mounted on either side of the roofline.

Lerner only remained in the building for two years but left behind its elaborate ghost signs. By 1985, Lerner was an 823-store chain and was acquired by The Limited. In 1992, the company changed its name to Lerner New York. The company changed its name again to New York & Company, or NY&C, in 1995.

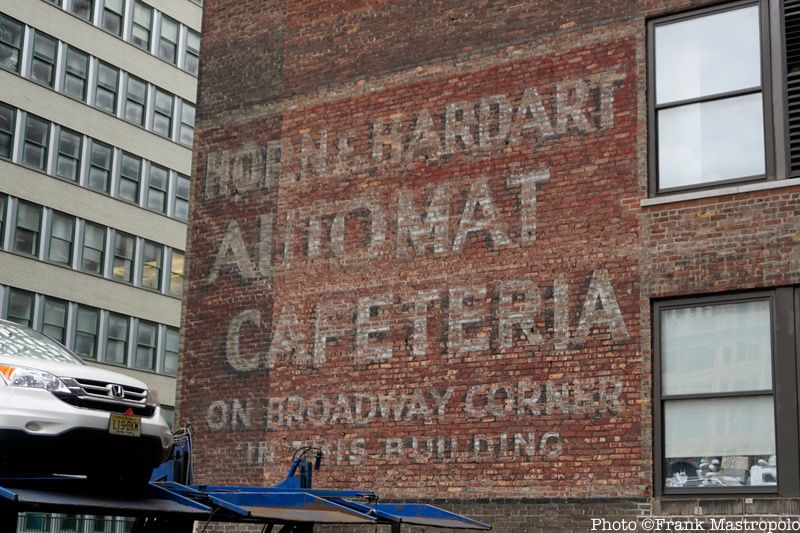

Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart opened their first restaurant, a small luncheonette with no seating, in Philadelphia in 1888. The pair opened their first Automat in Philadelphia in 1902, after Hardart was inspired by the “waiterless” restaurants he saw in Europe. Ten years later, Times Square was the site of the first Automat in New York.

Automats featured walls of small glass windows displaying prepared food. Customers fed a few nickels into a slot to enjoy favorites like macaroni and cheese, baked beans, and creamed spinach.

“For all the good food, the Automat’s real secret weapon was its coffee,” noted Smithsonian magazine. “Prior to the Automat, coffee was often harsh and bitter, boiled and clarified with egg shells. The Automat’s smooth aromatic brew flowed regally from ornate brass spigots in the shape of dolphin heads.”

At its peak, Horn & Hardart was the world’s largest restaurant chain, serving 800,000 people daily. Changing consumer tastes and the popularity of fast food led to the Automat’s demise. The last of New York City’s Automats closed in 1991. Horn & Hardart was recently resurrected by the film crew of the Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. A recreation of the former restaurant was built inside a Crown Heights church for the upcoming fifth season.

A ghost sign for the Automat remains partially visible from the sidewalk on 38th Street. A visit to the roof of the adjacent parking garage provides a complete view of the ad, which reveals its location “on Broadway corner in this building.”

That Garment District Automat at 1385 Broadway is recalled by Amelia Bucchieri in Placematters. “This Automat on 38th and Broadway was open for breakfast and closed mid-afternoon. It was a patternmakers’ hangout. Most people that worked in the area of 37th Street and 38th and Broadway brought from home their sandwich and only bought coffee from the Automat at 38th and Broadway until the manager would catch us. Coffee was only five cents.”

The 50-floor General Electric Building was built in 1931 as the RCA Victor Building. RCA at the time was a subsidiary of General Electric. RCA did not remain in the building long, moving to 30 Rockefeller Plaza in 1933. At that time the building was deeded over and renamed for General Electric.

The building was described as “one of the city’s most exquisite Art Deco jewels” by The City Review, Architect John W. Cross explained his concept in the May 30, 1931 issue of the Real Estate Record and Guide. “Romantic though radio may be, it is at the same time intangible and elusive — a thing which can be captured visually only through symbolism.”

As an illustration, a large clock with the famous cursive GE logo is above the main entrance. It is flanked by two disembodied arms that hold bolts of lightning. The lightning bolt motif, used throughout the building, depicts the radio transmission waves sent by RCA across the country. The building had to be designed to be compatible with the Byzantine dome of its neighbor, St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church, and was built with the same salmon-colored terra-cotta brick.

According to The City Review, “A sad commentary on the city’s office market is that in the depths of the real estate depression in the early 1990s, this building was donated to Columbia University because its owner could not rent its small floors at rates high enough to cover expenses.” After a $3.5 million renovation, Columbia was able to attract new tenants to the building. “It may not be the largest gift in the history of Columbia, but we believe it’s the tallest one,” said Dennis D. Dammerman, senior vice president of finance at General Electric, in 1993. The GE sign remains as a nod to the building’s past.

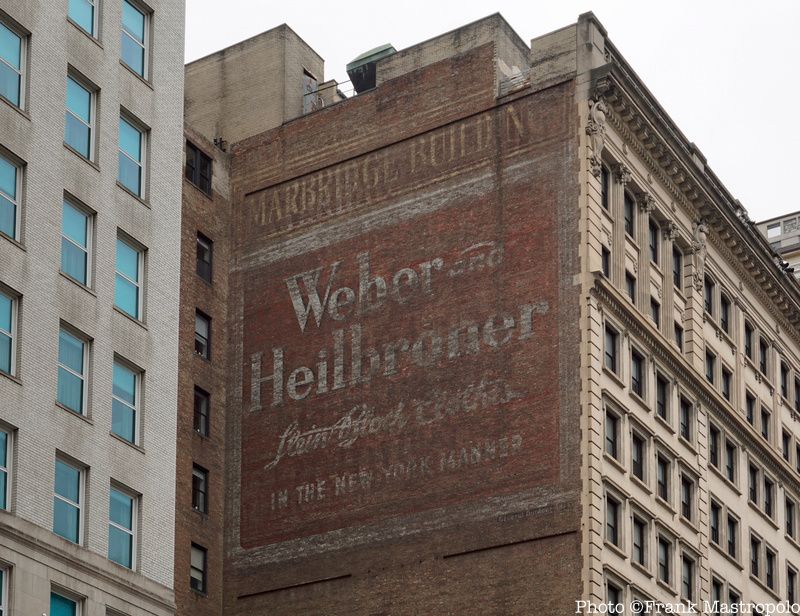

Weber & Heilbroner, “furnishers to men who know,” was a chain of men’s clothing stores founded by Milton Weber and Louis Heilbroner in 1902. The two entrepreneurs established their original haberdashery in about 1900 at 920 Third Avenue. The company expanded rapidly. By 1910, an ad boasted nine Manhattan locations. Its ghost sign remains on the side of the Marbridge Building in Herald Square. Ghost signs historian Walter Grutchfield writes that the Marbridge became available in 1922 when the men’s clothing store Rogers Peet moved across Sixth Avenue. Weber & Heilbroner opened there in 1923.

The ghost sign reads, “Stein-Bloch Clothes, in the New York Manner.” The River Campus Libraries site notes that Stein-Bloch “became a leader in the manufacture of high-priced, high-quality clothing. So skilled were the workers and craftsmen at Stein-Bloch that the company was once visited by President Andrew Johnson, formerly a tailor himself, who after his visit always wore clothes bearing the ‘Stein’ name.” The Margate Building store was one of the last to operate when Weber & Heilbroner went out of business in the late 1970s.

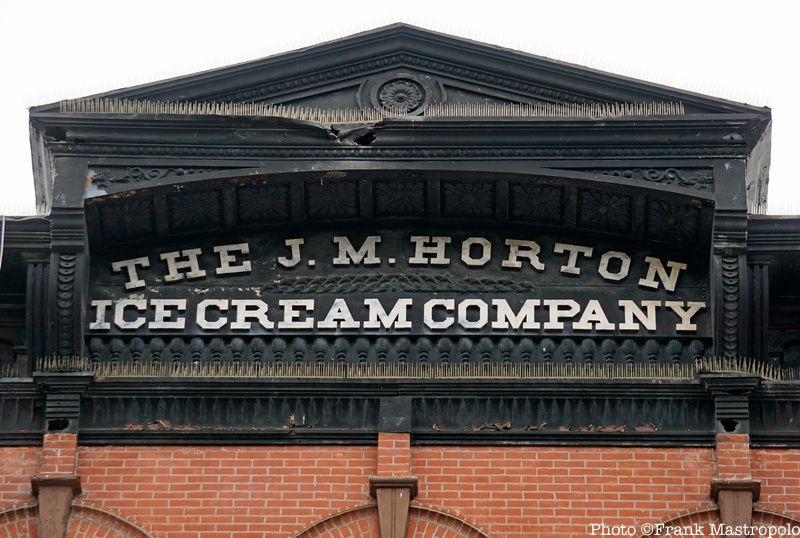

New York’s upscale Columbus Avenue is lined with yogurt, gelato, and traditional ice cream shops that cool off sweltering Upper West Siders; Venchi and Van Leeuwen are some of the fancier outposts. A ghost sign remains of a pioneer in the ice cream sweepstakes.

James Madison Horton founded J. M. Horton Ice Cream in 1870. By 1916, Horton supplied more than half of the city’s ice cream, producing more than three million gallons of the confection each year. Horton operated six stores in Manhattan and two in Brooklyn. Its ads called the company the “largest manufacturers of ice cream in the world.”

The Horton store on the Upper West Side opened in 1890. Its triangular pediment high above the street still displays the company name.

“Most building construction on Columbus Avenue followed the arrival of the Ninth Avenue el in 1881,” notes the New York Times, “and the fancy pediments on many former factory buildings were originally intended as rooftop advertisements, to be seen by riders on the trains passing overhead but are all but invisible from the sidewalk below.”

Customers could purchase ice cream from its street-level store but much of Horton’s business came from supplying hotels, restaurants, trains and steamships. Daytonian in Manhattan notes a Horton’s ad that boasts an impressive list of flavors: “Biscuit glace, tortoni, praline, tutti frutti, pudding nesselrode glace, stanley glace, diplomate plombiere and mousse cafe, marrons, mill frutti, cardinal, roman and lalia rookh punch.”

The Columbus Avenue address served as one of Horton’s factory buildings where ice cream was made by hand. As competitors switched to mechanized construction, Horton’s factory became obsolete. Horton was absorbed by the Pioneer Ice Cream Division of Borden in 1930.

“Fifteen years ago, A. S. Beck opened his first shoe store — on an idea,” read a 1925 ad in the New York Daily News. “He believed that if he were to put more style and more value than was customary for the price into the shoes he sold, the men and women of New York would be quick to recognize his efforts and he could look for his profits in increased sales, increased turnover and in additional stores. In A. S. Beck Shoes you get style, comfort and durability. There is not a fashion or last that the most exclusive shoe designer creates that does not find its way into A. S. Beck Shoes.”

Alexander Samuel Beck emigrated to America in 1888 from Eger, Hungary. Beck partnered with his brother Samuel and opened his first retail shoe store on Fulton Street in Brooklyn in 1909. The partnership was dissolved in 1914 and Beck opened another shoe store in Greenpoint.

By 1920, Beck’s business had expanded to 13 stores and was sold to the Diamond Shoe Corporation for $1 million. The agreement mandated that the company would always retain Beck’s name.

The chain was subsequently sold to Saul Schiff & Associates and by 1945 had expanded to 145 stores in 60 cities. But business dwindled over time and the final Beck’s shoe store, across 34th Street from Macy’s, closed in 1982. Beck’s huge ghost sign remains on the building that was built for the Beck chain in the 1920s. Its gold Art Deco signage mounted on gray stone tiles was reportedly designed by Harry L. Alper in the mid-1950s.

The Studebaker brand originated in 1852 when the five Studebaker brothers manufactured Conestoga Wagons. The company moved to electric, then gas-powered cars in 1902, which they produced until 1966. Studebakers are remembered as reliable cars that featured innovative designs.

The brick Studebaker Building in Manhattanville was built in 1923 with a white porcelain trim across its roofline. Two Studebaker terra cotta “turning wheel” logos used by the company between 1923 and 1934 are still visible on the southwest corner near the top. Cars were shipped from here to local dealers.

Customers could buy used Studebakers at the site. “A good car for your vacation can be secured for from $50 to $200,” read a 1926 New York Daily News ad. “Serviceable, sweet running automobiles — open or closed — are available at wholesale. Studebaker Pledge to the Public on used car sales guarantees you satisfaction.”

A decline in sales precipitated by the 1929 stock market crash forced Studebaker to sell the building to the Borden Milk company, which used it as a processing plant. The building later served as a warehouse for the American Museum of Natural History and other companies. Columbia University bought the building in 2000 and today its Computer Center and other departments are housed there.

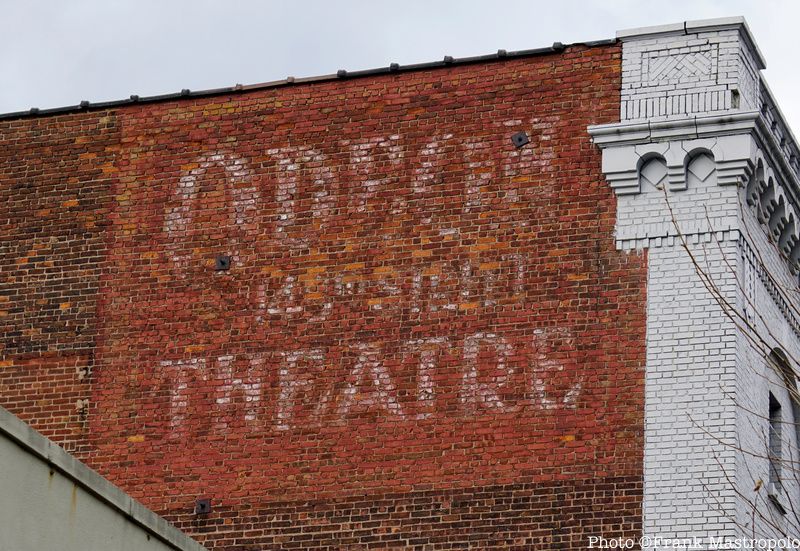

The Odeon 145th Street Theatre in Central Harlem opened in 1911. “The theatre is fireproof throughout and has a seating capacity of about 1,100,” The New York Times noted in 1911. “The theatre was opened with moving pictures and vaudeville performances early this year, and has been a success from the start.”

By 1925 Frank Schiffman and Leo Brecher, later owners of the Apollo Theater, converted the hall to show motion pictures exclusively. The Odeon 145th Street Theatre was named to differentiate it from the Odeon Theatre at 58 Clinton Street on the Lower East Side. Today the building is the home of St. Paul’s Community Church, which took possession of the building in 1952 and began extensive renovations. Ghost signs for the Odeon are visible on the upper side walls.

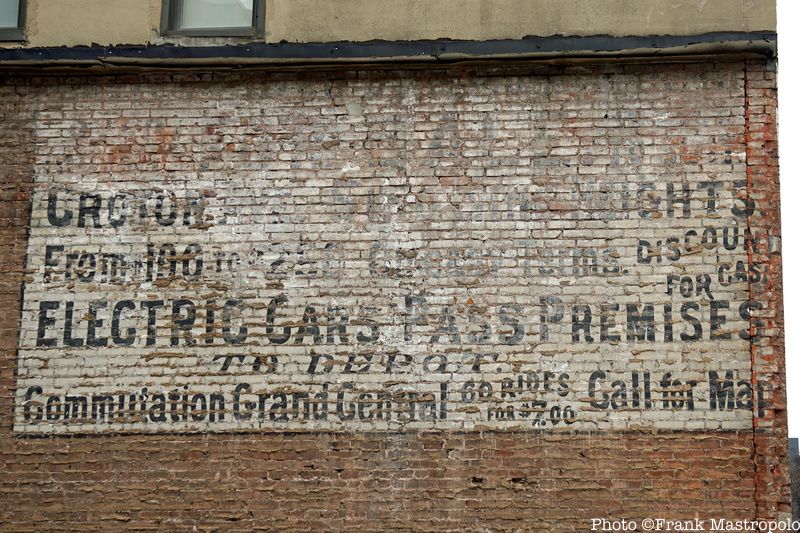

The removal of an exterior wall in Hell’s Kitchen during construction in 2016 revealed a puzzling sign that dates to the early twentieth century. What remains of the sign reads, “From 100 to 230, On Easy Terms, Discount for Gas, Electric Cars Pass Premises to Depot, Commutation Grand Central, 60 Rides for $7.00, Call for Map.”

The electric cars of the ad are trolley cars, also known as streetcars, which debuted in New York City in 1832. Steel tracks were embedded in the ground, which provided a smoother ride for commuters than their predecessor, horse-drawn carriages.

By 1909, notes Village Preservation, “Electric trolleys hit the urban scene of all five boroughs. The baseball team in Brooklyn was so-named because of the enthusiastic fans that had to ‘dodge’ the traffic en route to the stadium (in fact, the team’s original name was ‘The Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers,’ which was later shortened).”

The ghost sign advertises real estate, perhaps promoting land to the north of Midtown Manhattan. The reference to a depot offers a clue to its age. When it opened in 1871, the rail terminal on 42nd Street was named Grand Central Depot. By 1900, the depot was rebuilt and renamed Grand Central Station.

Rowland Hussey Macy opened his fancy dry goods store, which sold textiles and ready-to-wear clothes, in Lower Manhattan in 1858. In a fortuitous move, Macy rented space in his basement to Lazarus Straus in 1874. Straus supplied Macy with china, glass, and silverware. Straus became partners with Macy in 1888 and purchased the entire store in 1896.

Macy’s soon outgrew its original location and the Straus family moved the store to Herald Square in 1902. The new store was built in three stages. The first section, completed in 1924, extended half a block back from Broadway towards Seventh Avenue. Overlooking that section is a Macy’s ghost sign that is not visible from the sidewalk below. But sharp-eyed visitors to the Empire State Building’s 86th Floor Observatory can spot the faded sign.

Next, check out more ghost signs of NYC and a ghost storefront ! You can continue discovering ghost signs of Uptown Manhattan in the author’s new book Ghost Signs 2: Clues to Uptown New York’s Past

Subscribe to our newsletter