NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

Alphabet City is the eclectic home of legendary jazz musicians, a candy store owned by a 90-year-old immigrant, buildings featured in Rent, and a tree where a religious movement began. Alphabet City is a neighborhood within the East Village typically defined as the blocks between Avenues A through D and East Houston Street through East 14th Street. The neighborhood was a haven for Irish immigrants in the mid-1800s, German immigrants in the latter half of the 19th century, and Puerto Ricans since the mid-1900s, with large and historic Jewish and Black populations. The neighborhood is a true mix of old and new, with some buildings dating back well over a century (including one from 1827) next to more modern developments. This history has been documented in films including The Godfather Part II and the 1984 film Alphabet City, as well as the poems of Allen Ginsberg. For a glimpse into a dynamic, radical, and fascinatingly weird neighborhood, here are the top 18 secrets of Alphabet City.

Perhaps expectedly, Avenues A through D are the only ones in Manhattan that have single-letter names. As part of the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, which created Manhattan’s grid system above Houston Street, 1st through 12th Avenues ran at least up to Harlem, while avenues A through D were listed where Manhattan widened past 1st Avenue. This meant that Avenues A and B originally extended further north discontinuously. The northern parts of the former alphabetically named streets have since been renamed: Avenue A north of 14th Street was renamed Asser Levy Place from 23rd to 25th Street, Beekman Place by the United Nations, Sutton Place and York Avenue by the Upper East Side, and Pleasant Avenue in East Harlem. Likewise, Avenue B reappears as East End Avenue from East 79th to East 90th Street.

The adoption of the current name of Alphabet City is surprisingly contentious. Many believe the name was adopted in the 1970s or 1980s to attract real estate investors to the artsy neighborhood. At the time, there were a handful of names circulating, such as Alphabetland and Alphaville. Alphabet City had a rather negative connotation, as some in law enforcement would call the relatively unsafe Avenues C and D “Alphabet City.” The name eventually stuck, as did Loisada Avenue for Avenue C, as named by the area’s many Puerto Rican residents. Some rejected “Alphabet City” (and still do) as they believe it separates the area from the rest of the East Village and continues to carry out the legacy of the area’s decades-old connotation of being a gritty and drug-infested neighborhood with a nickname from the cops.

Tompkins Square Park, nestled between Avenues A and B, has a storied history that the newer restaurants and ornate rowhouses surrounding the park may not tell. As late as the 1990s, the park was a crime-ridden gathering place for the area’s homeless population. In 1988, riots were held at the park over a 1 a.m. curfew enacted to decrease the prevalence of drug pushers and homeless people in the park. The riots were violent clashes between protestors and police. Despite the park’s violent past, a tree still standing near the southern edge of the park tells a rather different, more peaceful, story.

The park houses a few American elm trees that survived a fungus called Dutch Elm Disease that ravaged the population of Dutch Elms in the 1930s. One of them, now called the Hare Krishna Tree, was where A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada and his disciples gathered in 1966 to host the first outdoor chanting session of the religious group’s mantra. The Hare Krishna movement, known formally as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, was founded in New York and bases its core beliefs on Hindu scripture as well as the practice of Bhakti yoga. A group gathered at the tree for over two hours chanting “Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare,” accompanied by a band of instruments. Today, the tree is considered the birthplace of the Hare Krishna movement, and followers continue to visit the tree to pay homage to its significance.

Also known as Kleindeutschland, Little Germany was a German immigrant neighborhood in Alphabet City and the East Village, as well as in parts of the Lower East Side. As early as the 1840s, the neighborhood (which was centered around Tompkins Square Park but consisted of about 400 blocks total) quickly became a center of German life. By 1855, New York’s German population surpassed every city but Berlin and Vienna. Many bakeries, groceries, craft stores, and cabinet shops opened on every block of the neighborhood, and many workers formed politically active trade unions. German immigrants lived with others from their state, settling in “wards” such as the Tenth Ward, which was mostly inhabited by Prussians. The area’s population grew to as many as 50,000 residents by the turn of the 20th century, many of whom spent time in Tompkins Square Park, or what they called Weisse Garten. Avenue B in particular was lined with beer gardens, libraries, sports clubs, and German synagogues, giving it the nickname German Broadway.

As younger residents moved to Brooklyn, the German population in the area slowly grew smaller. The number of German immigrants in the area was also impacted by the disastrous sinking of the General Slocum, a passenger steamboat, in 1904. Over 1,300 passengers boarded the boat for a picnic cruise on the East River run by St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church. A fire broke out in a storage compartment, and both the lifeboats and preservers were in disrepair, resulting in the deaths of 1,021 passengers.

The neighborhood struggled to handle so many deaths of loved ones and important members of the community, and many committed suicide as a result. This disaster, coupled with the growth of populations from Eastern Europe and growing anti-German sentiment, led the neighborhood to contract even more. Many Germans moved uptown to Yorkville or to other parts of the city. Today, a memorial fountain stands in Tompkins Park.

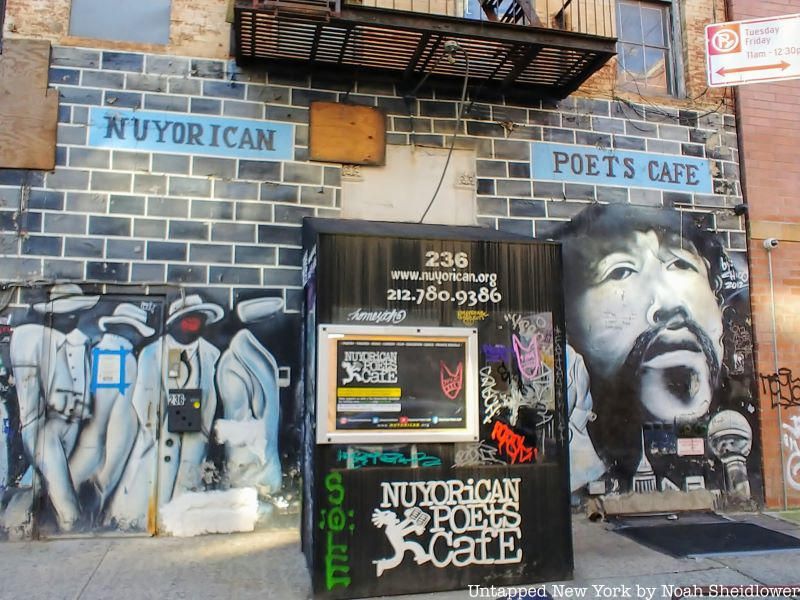

The Nuyorican Poets Cafe is one of the defining features of Alphabet City, serving as a home for the Puerto Rican cultural intellectual movement in New York City. Founded in 1973, the cafe has been a crucial part of the development of the city’s hip-hop, poetry, visual arts, and theater scene. Rutgers University professor Miguel Algarín co-founded the cafe with fellow Nuyorican Movement leaders Pedro Pietri, Miguel Piñero, Bimbo Rivas, and Lucky Cienfuegos. The original location was at Algarín’s apartment. In 1975, Algarín rented an Irish pub on East 6th Street, where he brought in leading Puerto Rican voices of the time. Eventually, the cafe moved to 236 East 3rd Street where it is today, inviting leading thinkers like Nancy Mercado and Giannina Braschi.

The cafe gained fame for its slam poetry scene in the acclaimed Open Room. Famous “battles” included figures like Bob Holman and Saul Williams. Poetry, often performed orally in front of large audiences, has been a major part of the cafe’s operations since it opened. The cafe has also put on events like the Nuyorican Poets Café Theater Festival. The cafe has since expanded to include other forms of art, such as its first full-length opera Carmen in 2015. Today, it is one of the defining features of what many refer to as “Loisada,” which refers to Avenue C and its particularly Nuyorican population.

Ray’s Candy Store, located at 113 Avenue A in the East Village, has been a local favorite for nearly 50 years. Known for its egg creams, beignets, and fried Oreos, Ray’s Candy Store has not changed much since opening in 1974, keeping its original cash register. Owner Ray Alvarez, an Iranian immigrant who moved to New York City in 1964, worked as a dishwasher for a decade before purchasing the store for $30,000. The store has survived it all, from staying open during the Tompkins Square Park Riot to dealing with the kidnapping and attempted murder of Curtis Sliwa in 1992 right outside.

For the past decade or so, the restaurant has fought to stay alive as rents have skyrocketed. The store was won numerous awards over the years that have brought more attention to it. The shop has appeared in numerous films including What About Me and Die Hard With a Vengeance, as well as media series by HBO and Vice News. In 2018, Ray’s was featured in the series finale of Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown. In November 2022, Ray’s employees launched a GoFundMe campaign for his 90th birthday party, as well as to recover some of the store’s losses from the pandemic. A mural was painted for the big day which took place on January 1st, 2023.

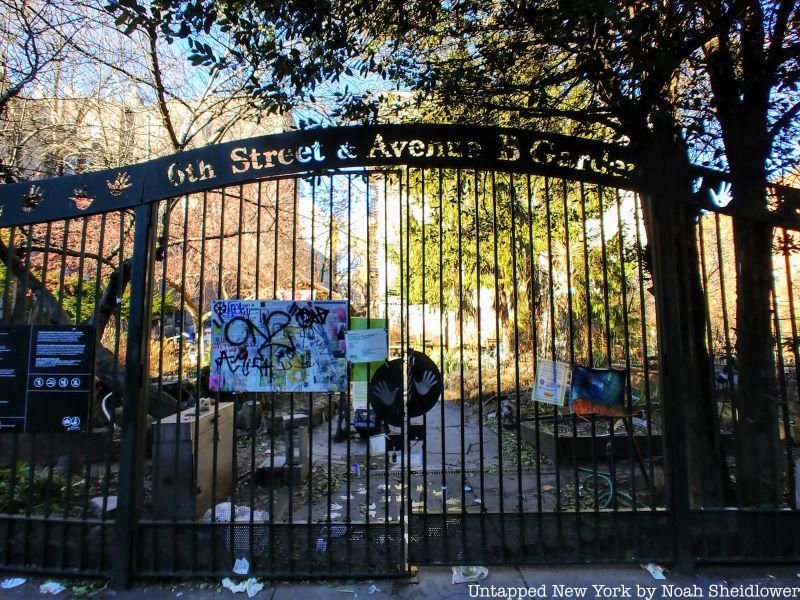

As with the East Village more broadly, Alphabet City has more community gardens than most (if not all) of the city. According to the GreenThumb Garden Map, there are about 30 community gardens between Avenues A and D and between East Houston Street and East 10th Street. This equates to almost one community garden for each block. One of the more notable ones is 6BC Botanical Garden (named for being on East 6th Street between Avenues B and C, as well as for “botanical” and “community”). 6BC was built in an empty, rubble-filled lot in the early 1980s, and over the last four decades, the garden has been cared for by volunteers and artists who have contributed their artwork. Many of the gardens, including 6BC, have faced threats of destruction by developers looking to build residential properties, though NYC Parks now protect many of them.

Another notable one is the Kenkeleba House Garden, an outdoor sculpture area of the Kenkeleba House art gallery. Named for a West African plant, the gallery and sculpture garden have featured artworks predominantly by African Americans, as well as other artists of color. The 6th Street & Avenue B Garden is another popular location with a small pond, a small stage, and lots of different plants. There are about five gardens within a block radius on Avenue C, including the 9th Street Community Garden, La Plaza Cultural, and the Flower Door Garden. Others are a bit more obscure, including the aptly named Secret Garden, Fireman’s Memorial Garden, and the Lower East Side Ecology Center.

The Charlie Parker Residence at 151 Avenue B is a Gothic Revival-style rowhouse that served as the home of the legendary saxophonist from 1950 to 1954. Built in 1849, the rowhouse stands four stories tall and faces Tompkins Square Park. Parker lived on the ground floor with his wife Chan Richardson and their three children. By the time he moved, Parker had achieved great fame for helping to develop bebop with Dizzy Gillespie and for releasing standards such as “Ornithology” and “Yardbird Suite.”

He continued performing with jazz groups large and small while living at the home, releasing the album Bird and Diz in 1952. He notably performed at Massey Hall in Toronto in 1953 with jazz greats including Charles Mingus and Max Roach, resulting in the album Jazz at Massey Hall. Though, not all was smooth sailing at the rowhouse; he continued using heroin, and his health started to deteriorate. He spent time in a mental hospital after the death of his daughter in 1954 from cystic fibrosis and pneumonia.

In 1955, at just 34, Parker died at the Stanhope Hotel on Fifth Avenue from lobar pneumonia and a bleeding ulcer, as well as from advanced cirrhosis. A stretch of Avenue B from 7th to 10th Street was renamed Charlie Parker Place in 1992, and the Charlie Parker Residence was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.

Prior to the development of the densely packed Alphabet City many know today, the area was for centuries a salt marsh. The area would regularly be flooded by the East River prior to and during the period of Dutch colonization. The Lenape took advantage of the wetlands for foraging shellfish and grass for weaving. Though the Dutch mainly settled at the lower tip of Manhattan, establishing villages near present-day Wall Street, settlers also used the wetlands for various purposes. The land in lower Manhattan was divided into “boweries,” or “farms” in Dutch.

What would become Alphabet City was divided into Bowery 2 to the north and Bowery 3 to the southwest. The southeast corner was divided into smaller lots. These farms near and within the salt marsh, referred to as “salt meadows” at the time, cultivated some crops and used plants like “salt hay” as fodder for livestock. As expected, this did some damage to the salt marshes, though the area was relatively lightly settled for the next century or two as the more southern parts of Manhattan developed more rapidly. It wasn’t until the early 1800s that the area became more industrial and developed.

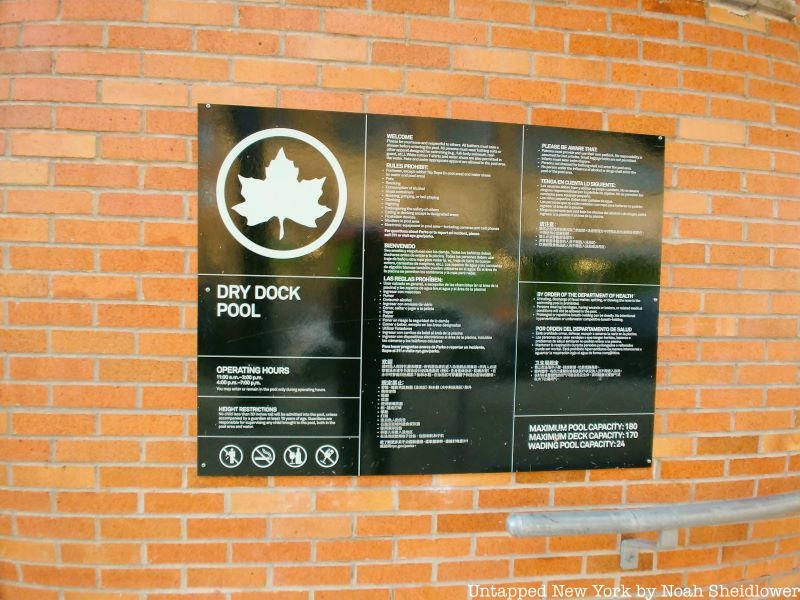

As Alphabet City developed into a commercial center, it quickly attracted the attention of shipbuilders and iron workers. Alphabet City, at the time known as the “dry dock district,” became a home for shipyards, and by the 1840s, 20 or so blocks by Avenue C produced more ships than anywhere else in the country. Around what would become Alphabet City, shipbuilders constructed Robert Fulton’s North River Steamboat, often considered the first commercial steamboat, in 1807. The boat was owned by Fulton and politician Robert Livingston, who obtained the exclusive right of steam navigation on the Hudson River. The boat measured 142 feet in length with a maximum width of 18 feet, and its first voyage went to Albany and back.

After plans were rejected for a food market between 7th and 10th Street, shipowners and builders helped construct more repair and construction facilities along the East River. Despite major debate about negative environmental impacts, this boosted the local economy, especially with the success of shipbuilders including Smith & Dimon, William H. Webb, and Jacob Westervelt. Ironworking firms like Novelty Iron Works employed well over 1,000 people, which led to rapid housing development along Avenues D and C. Contrary to many other industries in antebellum New York City, shipbuilding paid workers a fair wage and kept work days to a maximum of 10 hours, meaning workers could afford nicer homes in the area.

As the name suggests, First Houses, located on Avenue A and East 3rd Street, was one of the country’s first public housing projects. Built in 1935 to 1936, the project consists of eight four- and five-story buildings collectively housing 122 apartments. The first tenants moved into the apartments on December 3, 1935. They were designed by Frederick L. Ackerman, who focused predominantly on working-class housing while working with the New York City Housing Authority. The apartments replaced Victorian-era tenements that were cleared due to their instability, which was NYCHA’s first-ever project. Many bricks from the original tenements were reused for First Houses.

The apartments cost significantly more than anticipated, though they allowed for more light and air thanks to the inclusion of courtyards. The project had “taken the question of public housing out of the realm of debate and into the realm of fact,” said NYCHA chairman Langdon Post. The apartments were an important example of eminent domain, as the previous tenements could not be safely repaired and the need for lower-income housing was rather dire. At the time, residents paid just $5 to $7 a month. in rent. They were greeted with animal sculptures commissioned by the WPA. The apartments were designated a National Historic Landmark in 1974.

Given Alphabet City’s artsy reputation, it may not come as a major surprise that Allen Ginsberg of the Beat Generation lived in the neighborhood alongside a few other leading Beat figures. Many musicians, authors, and hippies settled in Alphabet City and the East Village after getting priced out of Greenwich Village, which was rapidly gentrifying in the 1950s. Ginsberg settled in a third-floor apartment at 206 East 7th Street. He lived there with his long-time lover William S. Burroughs from 1952 to 1953. The apartment was a hangout spot for other Beatniks including Jack Kerouac, pictured looking out the apartment window in a famous photograph, and Gregory Corso. The apartment was comfortably situated between Avenues B and C, both of which had cafes and hangout spots for the Beats.

Ginsberg would later move to San Francisco to complete his famous poem “Howl.” He soon moved back to New York when he was done. This time around, he moved into an apartment at 170 East 2nd Street between Avenues A and B. He lived in this apartment for three years with his partner Peter Orlovsky. It was in Apartment 16, a walk-up, where he wrote his arguably second-most famous poem “Kaddish,” a mournful elegy for his mother.

Amid the historic apartments of Alphabet City, many dating back a century or more, there are a handful of fascinating architectural marvels. One of the standouts is the Flowerbox Building, located at 259 East 7th Street between Avenues C and D. Built in 2007, the Flowerbox Building includes a vertical garden that waters itself. The building was developed by Seth Tapper, who grew up on the block and whose father David Tapper created the documentary The Street of the Flower Boxes about the block. Between each 12-foot-high floor-to-ceiling window are 18-inch-deep planters that are self-irrigating, containing upwards of 80 different plant species. The seven-story building has just eight units, which have sold for as much as $2.6 million.

Another building that stands out from the rest is located at 246 East 4th Street on the corner of Avenue B, which the Village Voice described as “the most colorful apartment building in NYC.” The bright purple building is accented with dark reds by each floor and the roof, as well as blues and golds.

This was the idea of Antonio “Tony” Echeverri, the building’s owner who repaints the facade every five years using paints he mixes by hand. Hidden away are sculpted angels on the upper stories, as well as fish and pelicans by the interior staircase. Echeverri acquired the building in 1992, a risky decision considering the apartment had hundreds of violations. Eventually, he worked with his team to not only fix up the building but also decorate it so it would please passersby and artists alike.

The Pyramid Club, which recently shut down at 101 Avenue A in October 2022, was an Alphabet City nightclub that had a major influence on the arts and drag scene of the city. After the Stonewall Riots, greater attention was devoted to drag performances throughout the city, and in the 1970s and 1980s, the Pyramid Club became a center for some of the most famous drag queens of all time including Lady Bunny and RuPaul. Years before hosting his namesake Drag Race, RuPaul had one of his earliest-ever performances in 1982 at the club. It wasn’t until 1989 that he achieved national fame. The outdoor drag festival Wigstock began in 1984 at Tompkins Square Park and was led by Lady Bunny.

In addition to drag performances, some of the most famous bands in history have performed at the club. Bands like Nirvana and the Red Hot Chili Peppers gave their first New York City performances here. Madonna’s first AIDS benefit concert was hosted at the club, just a few blocks from her former apartment. Andy Warhol also appeared in an MTV feature for the club, which had been frequented by Keith Haring and other figures in the LGBTQ movement. Attempts to landmark the club as a “drag landmark” failed, even despite performances from dozens of legendary performers. The building is part of the East Village/Lower East Side Historic District which was designated in 2012. The club closed at the beginning of the pandemic and reopened in briefly 2021 only to shutter again in the fall of 2022.

The Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space may seem unassuming from the exterior, but inside is a museum dedicated to archiving the Lower East Side’s community gardens and squatting history. The museum’s exhibits document how residents of Alphabet City and surrounding neighborhoods have turned abandoned lots into gardens and squats, or the oftentimes illegal occupation of unoccupied or abandoned buildings or land. The museum itself is located in the storefront of C-Squat, a former squat house at 155 Avenue C that dates back to 1871. The building housed squatters in the 1980s and 1990s before its restoration. Squatting was particularly prevalent during the 1970s recession when the city reduced funding for many essential social services. These difficult economic conditions led residents of Alphabet City to push for housing reform, helping transform abandoned properties into not only squats but also community centers and communal homesteads.

The museum itself was founded in 2012 with permanent exhibitions exploring Alphabet City’s radical history, the Occupy Wall Street movement, and sustainable activism. Recent exhibitions have included “Stop the Invasion,” focusing on art protesting the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a history of squatting movements, and a look into the East Village’s 39 remaining community gardens that have been particularly influential for lower-income communities. The museum also leads Lower East Side radical history tours on weekends and has hosted open vault nights and an annual film festival on occupations.

St. Brigid Roman Catholic Church, located at 123 Avenue B, has had quite a storied past. The parish was organized in 1847, and construction on the church began in 1848. It was built by recent immigrants who fled the Irish Potato Famine. Irish-American architect Patrick Keely, who immigrated in 1842, led the construction of the church, which originally was a haven for recent Irishmen who came to the U.S. with almost nothing. Reverend Thomas Mooney, the church’s second pastor, was a chaplain of the 69th New York Infantry Regiment, nicknamed the “Fighting Sixty-Ninth.” Poet Joyce Kilmer wrote about the unit in “When the 69th Comes Back,” which focuses on the regiment’s Irish history. Mooney’s dedication to the regiment was so great that he baptized a cannon, which may have led to his recall.

Mooney’s community activism continued with the 1863 draft riots, during which he organized members of the community to oppose federal troops. His support of the Irish regiment lasted until his death, which was around when the church’s demographics began to diversify. As different ethnic communities joined the church, its activism did not stop; during the 1970s and 1980s, the church helped keep the local community safe and fed, providing a space for community members to mobilize during the 1988 Tompkins Square Park Riot. The church’s pastor was arrested for crossing the police line to deliver food to protestors during a series of 1989 riots.

Just a few doors down from the Charlie Parker Residence is the Christodora House, located at 143 Avenue B, which was designed as a settlement house. The settlement movement, which had its roots in the United Kingdom, strived to bring together wealthier and poorer communities. Settlement homes were developed in poor urban areas and were staffed by volunteers from the upper and middle classes in an attempt to alleviate poverty and provide better opportunities for at-risk populations.

The Christodora House opened in 1928 and included services including a gym, theater, and music school, as well as office space and two kitchens. The lowest five of the building’s 16 stories housed all the resources, while the top nine were rented out as residences. However, the cost of maintaining a settlement home, especially during the Great Depression and World War II, proved too much. It was sold to the city in 1948, after which it may have served as a headquarters of the Black Panthers and condominiums for wealthier residents. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986, acknowledging the building’s role within the community.

Also on Avenue B, at its intersection with East 8th Street, was the Children’s Aid Society’s Tompkins Square Lodging House for Boys and Industrial School. Built in 1887, the building, also called the Eleventh Ward Lodging House, was a shelter for lower-class boys, many of whom worked as newsboys or shoeshiners. The home was opened about three decades after the founding of the Children’s Aid Society by Charles Loring Brace. At the time, abandoned and orphaned children lived in New York’s slums and on the streets, and Brace opened centers to educate and train children for employment while breaking them from their pasts; though, the program was met with some hesitation from abolitionists and Catholics. The Alphabet City building was designed in part by Calvert Vaux and is the oldest extant Children’s Aid Society building, built in the High Victorian Gothic style.

One of the most famous musicals of all time, Rent, takes place in Alphabet City amid the HIV/AIDS crisis. The musical tells of a group of impoverished artists hoping to make a life for themselves, taking inspiration from Puccini’s 1896 opera La Bohème. The neighborhood was chosen because of its starving artist culture but also in part because playwright Jonathan Larson lived in Alphabet City throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

Many of the locations mentioned in the musical are real and still stand today, though not in their original form. Alphabet City also inspired the satirical location in Avenue Q, as well as “Alphabet Land” in Angels in America.

In the musical Rent, the characters live at the intersection of 11th Street and Avenue B. They would often frequent Life Cafe, which was located at 343 E 10th St. but went up for sale in 2012; the space is now a tattoo parlor. At the end of Act 1, the riot after Maureen’s performance took direct inspiration from the Tompkins Square Park Riot. The neighborhood’s LGBTQ advocacy groups such as the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and ACT UP! also inspired the group support meetings in the musical. The 2005 film adaptation also includes scenes shot in Alphabet City and many shots in San Francisco.

Alphabet City’s history of arts and progressive counterculture has attracted dozens of up-and-coming celebrity residents over the last few decades. Perhaps the most notable was Madonna, who came to New York City from Michigan at just 19 years old. Madonna Louise Ciccone moved to New York in 1977 with just $35 in her pocket, settling in a spare bedroom in apartment 3-B at 270 Riverside Drive. The apartment was shared with Saul Braun, whose son Josh co-wrote a few of Madonna’s first songs. After a year, she moved to 232 E. 4th St. in a fifth-floor walkup. While living here, she performed with various bands including Breakfast Club, later releasing her debut single “Everybody.” Her Alphabet City apartment was described as “two small rooms, no furniture except a big white futon, and a perpetually hissing radiator” by her brother.

While his Central Park West apartment was more notable, Bruce Willis lived in Alphabet City during the early 1980s before rising to fame on the television show Moonlighting. Geraldo Rivera, the television personality and political commentator, also lived in Alphabet City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Members of the rock band The Strokes resided in the neighborhood, as did actor Bobby Driscoll and artist Kiki Smith.

Next, check out the Top 12 Secrets of the East Village!

Subscribe to our newsletter