After-Hours Tour of "Noguchi's New York" Exhibit

Join an exclusive curator-led tour at NYC's Noguchi Museum!

We love a good lost building here at Untapped New York. In the past, we’ve covered lost department stores, lost amusement parks, and lost structures of the World’s Fair. After recently covering the lost mansions of New York’s Hudson Valley, we’re diving into the archives to recover the lost mansions of all five boroughs, starting with the lost mansions of Brooklyn. While many of these forgotten homes were demolished nearly a hundred years ago, some of these extravagant single-family homes lasted well into the 20th and 21st centuries. There are still gorgeous mansions that you can see throughout the borough today, but here, we explore those that have been lost to time, from a pre-Revolution party house to a controversial failed landmark:

The Prentice mansion was originally built by merchant Charles Hoyt in 1835 on farmland bordered by today’s Remsen, Joralemon, and Hicks Streets and the East River to the west. John Hill Prentice, a fur merchant, purchased the Brooklyn Heights property in 1840 and moved in with his wife and their 18 children. Prentice had the mansion moved to 1 Grace Court from its original location along Remsen Street. He also added an additional story to the large wooden house. On three expansive terraces that cascaded down from the front of the house, there were various fruit trees including pear, apricot, peach, fig, and nectarine. John’s Prentice Stores warehouses and docks were not far from the grand home.

One of the most elaborate features of the mansion was a fountain circle which John, who served as president of the Water Board, had installed to celebrate the introduction of water to Brooklyn from Nassau Water Works. Prentice also served as one of Brooklyn’s first parks commissioners. After Prentice died in 1881, the mansion was occupied by his younger brother James. By 1904, the mansion was in disrepair. It was torn down in 1909 and replaced by a six-story apartment building in 1925. This apartment building is what you’ll find at the site today.

Located right across from the Prentice Mansion was the brick mansion of John’s business partner, William Satterlee Packer. At 2 Grace Court, Packer built an impressive mansion for himself and his wife Harriet. Harriet had been the live-in governess for the Prentice children when she and William met. The mansion was designed by English architect Richard Upjohn and completed in 1850. William, unfortunately, did not get to enjoy his mansion for long. He died in December 1850 and Mrs. Packer continued to live in the home.

In a Brooklyn Daily Eagle article from 1916, the reporter notes the home’s “stone balcony of Gothic design” at the entrance, and the Grecian-style hand-painted ceiling of the drawing room, “but the most interesting thing in the house was the Italian marble mantel.” It was an imitation of a design by Dutch sculptor Bertel Thorwaldsen, which Mrs. Packer had custom-made in Italy. Another interesting feature of the home was the stained glass rotunda which sat below the attic. “At night gas jets would shed gleaming rays of light through the dome giving the hallways the appearance of a fairyland,” the reporter wrote.

The Packer mansion was a popular spot for visiting dignitaries, poets, musicians, and artists. In honor of her late husband, Mrs. Packer founded the Packer Collegiate Institute on Joralemon Street in 1854 after the original Brooklyn Female Academy (BFA) burned down.

The Packer family lived in the home until the early 1900s when it was purchased for $147,000. The mansion was demolished in 1916 and the site was temporarily used for tennis courts. In the 1920s, a massive apartment complex was built at the site, and remains today.

In the early 20th century, the St. Mark’s District of Brooklyn was the place to be for the borough’s wealthiest residents. Located in what is now the Crown Heights North Historic District, this ritzy neighborhood boasted many elegant mansions. One of the most grandiose of these homes was that of typewriter tycoon Clarence Seamans. Standing at 789 St. Marks Avenue, Seamans’ four-story masonry house was designed by architect Montrose W. Morris. Many homes on St. Marks Avenue were of Morris’ design.

Built around 1904 in the Italian Renaissance Revival style, the limestone-clad mansion had all the things you would expect in a home of its size: a bowling alley, ballroom, swimming pool, and an underground passageway that connected the main house with the carriage house. Morris and Seamans traveled to Europe to buy furnishings for the home, sometimes purchasing whole rooms. Seamans’ wife sold the mansion in 1918, and in 1922, it became Chateau Rembrandt, an event space. By 1928, the event space had closed, and the final private owner moved out. The mansion was torn down to make way for The Excelsior apartment complex.

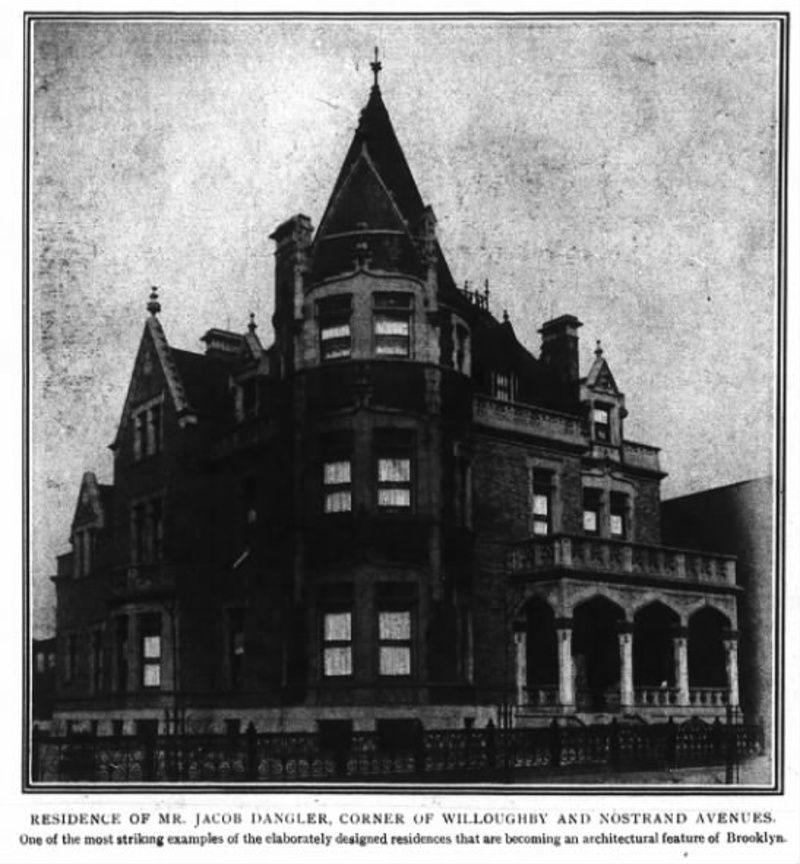

Jacob Dangler was a German immigrant who arrived in New York in 1868. After working for other German grocers and learning about the business of provisions from them, he built his own company and fortune on processed meats. To show off his wealthy status, Dangler had a mansion built at the corner of Willoughby Avenue at Nostrand Avenue. It was designed by noted German American architect Thomas Engelhardt, who had previously designed Dangler’s factories and other buildings related to his business. According to Brownstoner, the mansion cost an estimated $50,000 when it was complete.

The French Gothic, brick and limestone mansion that Dangler built stood out among the more modest and middle-class rowhouses that surrounded it. An article in The Brooklyn Citizen from 1898 points out the many features of the home including a basement bowling alley, steam heat, and electric lighting. It goes on to describe the many rooms including a library, well-appointed bathrooms, a billiards room, a sitting room in the tower, a sewing room, a laundry, and a music room finished in mahogany with floors “varnished and without rugs in order to enhance the acoustic effects.”

The house was put up for sale in 1940. It was used by a variety of organizations including the Knights of Pythias and the Oriental Grand Chapter of the Eastern Star, a masonic organization. After much pushback from the local community (even actor Edward Norton) and a failure to gain landmark designation, the house at 441 Willoughby Ave was demolished in the summer of 2022.

The current owner has proposed a 44-unit 7-story high-rise apartment building for the site. A group called Justice for 441 Willoughby is fighting the future development of the site. Instead, the group is calling for the current owner to rebuild the mansion.

This grand home which once stood at the corner of Henry Street and Joralemon Street was built for Edwin Packard, a successful merchant who worked for the department store A.T. Stewart & Co. Edwin and his wife had three daughters, Mildred, Elizabeth, and Clara, who were all well known in Brooklyn society. Their home at 241 Henry Street was constructed in the 1880s.

A Brooklyn Daily Eagle article describes the home as “unique and picturesque” with its many gables, jagged roofline, bay window, and parapet. Inside, the rooms were “cozy and oddly shaped and had the most perfect street views.” The home was demolished in 1950 to make way for a new apartment building.

In The Social History of Flatbush and Manners and Customs of the Dutch Settlers in Kings County by Gertrude Lefferts Vanderbilt, the author described the Wilbur mansion, completed in 1878, as “highly ornamental.” It stood on what was once the Martense farm, one of the largest Dutch farms in the area. Judge Martense built the ornate frame home for his granddaughter, the wife of Lionel Wilbur.

The home at 684 Flatbush Avenue stood next to a stately mansion that Judge Martense built for himself. The house was demolished in the early 1920s as the area became more developed. The Judge’s neighboring house, which can be seen in the photograph above, was also demolished.

In the 1840s or 50s, newspaper publisher and dry goods merchant William C. Bowen moved into this Greek Revival mansion at 90 Willow Street. Bowen, who was an abolitionist, is reported to have entertained Abraham Lincoln in this home before he became president (though other reports say he declined the invitation to work on a speech which he was to give later that evening at Cooper Union). Lincoln did attend a service at Plymouth Church, which Bowen was a founder member of, to hear Henry Ward Beecher. Beecher had edited and contributed to Bowen’s paper, The Independent, and would become embroiled in a scandal when it was revealed that he was having an affair with another editor’s wife.

After Bowen’s death in 1896, his children continued to live in the house. In 1903, the interior furnishings of the house were auctioned off in a large sale. “Fine old mahogany and rosewood furniture, valuable paintings, etchings and engravings, chandeliers, mirrors, china, glassware, carpets, draperies, and the like,” were all sold “for a song” according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The mansion was sold to a developer who planned to knock it down and build a hotel. Many in the community mourned the loss of yet another grand home. One person who wrote in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle called the destruction of the house a “source of great regret to many an old Heights boy and doubtless to many other old Brooklynites.” While plans for the hotel never came to fruition, a large apartment complex was built at the site.

Geroge Pope inherited a fortune from his brother and poured the money into making his Buschwick home as lavish as possible. Geroge’s brother John built a fortune in the tobacco industry. When he met an untimely death, his millions were distributed amongst his friends and four siblings. While his three sisters got a mere $140,000, the bulk of the fortune went to his brother George.

Inside the mansion at 871 Bushwick Avenue, George filled the rooms with 22k-gold chandeliers, expensive oriental rugs, pianos, and ornate stained glass windows likely by Tiffany. He even spent $140 on a white peacock for the yard. George, like his brother, died young, at the age of 48. The mansion, which had been valued at $2 million dollars, was sold to the Jewish Home for the Aged and Infirm (later known as the Menorah Home) for just $150,000. The mansion was demolished in the 1950s.

The Clarkson Mansion at 112 Kenmore Place was built in the 1830s in a Greek Revival style. The front facade boasts 6 Corinthian columns and a wide open porch. After the Clarkson family left, the house was taken over by the Midwood Club and became a social hot spot. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote that the Club added a Dutch room in the basement with tiles imported from Holland and a log cabin room with a large fireplace. Throughout its history, the building was also home to the Union League Club and the Flatbush Y.M.C.A.

After a fire ravaged the building in the 1940s, the Y.M.C.A determined that it was too costly to repair. The organization sold the building, which they had referred to as the Sperry Memorial Building, to developers. An apartment complex now stands at the site. Rooms from the Clarkson Mansion were recreated in an exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum in 1944.

Melrose Hall was a pre-Revolution home built near what is now Bedford Avenue, between Winthrop Street and Clarkson Avenue. The home is filled with ghost stories and legends. Built for an English settler, it was later owned by British Colonel William Axtell. Legend says that Axtell kept rebel soldiers in a secret dungeon prison and that those soldiers haunted the house. During Axtell’s time at the house, it was known as a place of wild parties, taking full advantage of the home’s large ballroom. After the war and Axtell’s residency, the home was acquired by the Mowatt family.

Mrs. Anna Cora Mowatt is the one who gave the home its name Melrose, for the beautiful rose bushes that grew on the property. The Mowatts only lived at Melrose for five years. In the 1880s the home was under the ownership of Dr. Homer Bartlett. Bartlett tore down all the extraneous wings and kept solely the central main house. He also started to sell off pieces of the land for development. When Bartlett died, the house was purchased by William Brown. An avid horticulturist, he purchased the property for its grounds. He built many greenhouses and conservatories and used the main house to host charitable functions, while he lived in another mansion nearby. After Brown, the house fell into disrepair and was vandalized by kids who explored its empty rooms searching for ghosts. It was sold to a developer in 1903 and demolished. The 19th-century rowhouses which stand on the former site of the hall have since become part of a designated historic district.

Next, check out some mansions that still exist! 10 Gold Coast Mansions of Long Island and A Guide to Victorian Flatbush

Subscribe to our newsletter