Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

For the last few hundred years, New York City has been one of the country’s epicenters of African-American and Black culture, from early free Black settlements in the 1820s to musical icons in the 1930s to modern-day Black activists. All throughout the city there are historic sites where influential Black figures lived and practiced their craft, from the Lewis Latimer House in Flushing to the Claude McKay Residence in Harlem. According to writer Laura Itzkowitz (an Untapped New York contributor and former managing editor) in her article for Architectural Digest “When Architecture and Racial Justice Intersect,” only 2% of the nearly 95,000 entries on the National Register of Historic Places focus on the experience of Black Americans, but you don’t have to search hard to find an abundance of sites connected to Black history around New York.

New York City is fortunate enough to have many relics of African-American struggles and victories preserved as landmarks. Yet there are many others, especially in the Bronx, that are forgotten or at best, commemorated only by a plaque. Here is our guide to Black historic sites in New York City across the five boroughs, including both landmarked and un-landmarked sites. Some have historic plaques, others do not.

We have organized the locations by date first built, but in some cases the connection to Black history may have occurred later than when the building was originally built, started in an earlier building that has been demolished, or have been connected to the site since the very beginning. This is by no means an exhaustive list but we attempted to highlight here sites that should be known to the public as well as those that have slipped under the radar.

The African Burial Ground National Monument is found in the Civic Center area of Lower Manhattan that contains the remains of more than 419 Africans from the 17th and 18th centuries. It is estimated that there were as many of 10,000 to 20,000 burials in the 1700s, and it is considered New York’s oldest African-American cemetery.

In the 1600s, the Dutch West India Company brought over slaves from Angola, Congo, and Guinea, and by the mid-17th century, a village called the Land of the Blacks saw 30 African-owned farms in modern-day Washington Square Park. It was estimated that 42% of households in New York had slaves, which eventually totaled about 2,500 by 1740. Slavery was ultimately abolished on July 4, 1827, yet only one-third of the city’s blacks were free in 1790. The site was initially labeled on old maps as “Negro Burying Ground,” and the first recorded burials for people of African descent occurred in 1712, but it is speculated that the burial ground was in use two decades earlier.

Some of the bodies of the deceased were illegally dug up for dissection, which sparked the 1788 Doctors’ Riot. The city shut down the cemetery in 1794, and urban development began taking place over the burial ground. The land remained largely forgotten until bones were discovered in 1991 during an archaeological survey by the General Services Administration. Protests occurred just a year later after it was discovered that the GSA had damaged some of the burials and took little care in excavation efforts. George H.W. Bush signed a law to redesign the area and to install a $3 million memorial, which was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the role of Africans and African Americans throughout New York City’s history. In 1993 the African Burial Ground was designated a New York City Landmark and a National Historic Landmark. It is also a National Historic Monument.

The Dyckman Farmhouse is Manhattan’s oldest remaining farmhouse, built around 1785 in the Dutch Colonial style. The home is situated in a small park in Inwood on the corner of Broadway and 204th Street, and today it serves as a New York City Landmark and a National Historic Landmark. William Dyckman, who constructed the home, died just three years after constructing the farmhouse, yet his son Jacobus would later inherit the house along with his wife Hannah, his eleven children, and a number of slaves and free blacks. Today, Inwood is home to a forgotten slave cemetery believed to have the remains of a number of the Dyckman family’s slaves.

As part of the DyckmanDISCOVERED initiative, the museum has investigated the stories of those enslaved by the Dyckman family. In 1820, a free black woman, a free black boy, and an enslaved man inhabited the home, and it is estimated that seven or eight slaves lived in the house when it opened. It was believed that freed blacks and enslaved workers would have used the house’s Summer Kitchen, a small one-and-a-half-story building adjacent to the farmhouse. A free black woman named Hannah worked as a cook for the Dyckmans and was born between 1784 and 1794. Although it was believed that the home housed a number of enslaved workers, the only one fully identified was Francis Cudjoe, who was set free in 1809. An official document stated:

“Recorded for and at the request of Francis Cudjoe this 11th day of January 1809. Know all men by these present that I Jacobus Dyckman of the City of New York on consideration of motive of humanity and sum of one dollar to me in hand paid Do hereby manumit and set free a Black man named Francis Cudjoe aged about Forty years. In witness whereof I have hereunto subscribed had my name and affixed my seal this eleventh day of January Anno Dominis one thousand eight hundred and nine. Jacobus Dyckman, Witness Peter.”

Seneca Village was a settlement in the 19th-century in present-day Central Park, founded in 1825 by free blacks. With a population of around 250 residents at its peak, the village featured three churches, a school, and two cemeteries. Bounded by 82nd and 89th Streets, Seneca Village would exist for over three decades before villagers were ordered to leave due to the construction of Central Park.

A white farmer named John Whitehead bought the land in 1824 and sold three lots of it to an African American man named Andrew Williams and twelve lots to the AME Zion Church. After the outlawing of slavery, many African Americans began to move into the village from downtown. A number of Irish immigrants fleeing the Potato Famine also settled in the village. Most of the homes were well-constructed, two-story buildings, the Central Park Conservancy tells us, rather than shanties which were in the minority of the buildings. Workers typically were employed in construction and food service, with many women working as domestic servants. The African Union Church in Seneca Village was one of the city’s first black schools, named Colored School 3.

The Seneca Village Project, founded in 1998, was created to raise awareness of the settlement’s history as a middle-class, free black community. Today, a plaque commemorates the site where Seneca Village once stood. There have also been recent archaeological excavations to uncover traces of Seneca Village, and in 2011, researchers discovered foundation walls of the home of William Godfrey Wilson, who was a sexton for All Angels’ Church in the village. 250 bags were filled with artifacts during the digs, including the leather sole of a child’s shoe. Central Park recently celebrated the history of Seneca Village through new historic signage as well as free tours during Black History Month, of which Untapped New York partnered with the Conservancy to offer a special tour to our Insiders members.

Sandy Ground was a community in Rossville, Staten Island, that was founded by free African Americans around the year 1828. Only a few months after slavery was abolished in New York City, an African American man named Captain John Jackson purchased land in the area, and the area quickly became a center of oyster trade. Many settlers would harvest and sell oysters at the nearby Prince’s Bay.

Sandy Ground was also an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and the settlement is currently considered one of the oldest continuously settled free black communities in the U.S. A church, a cemetery, and three homes from the settlement are today designated as New York City landmarks, yet most of the original houses were destroyed in a 1963 fire. Today, the Sandy Ground Historical Museum is home to the largest collection of documents detailing Staten Island’s African-American culture, history, and freedom.

Like Seneca Village, Weeksville was a neighborhood that was founded by free African Americans, situated in modern-day Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Weeksville was founded in 1838 by James Weeks, an African-American longshoreman who bought land from Henry C. Thompson, a free African American land investor. The land was previously owned by an heir of John Lefferts, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

By the 1850s, Weeksville’s population had surpassed that of Seneca Village, with upwards of 500 residents from across the East Coast, with over a third of residents born in the south. Weeksville was home to two churches, a school (Colored School No. 2), and a cemetery, as well as the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. Weeksville also had one of the first African-American newspapers called the Freedman’s Torchlight and served as headquarters of the African Civilization Society. Additionally, the area was a refuge for many African Americans who left Manhattan during the 1863 Draft Riots. Four historic houses dating back to the time of the village collectively make up the Hunterfly Road Houses, listed on the NRHP in 1972. The discovery of these houses led to the creation of the Weeksville Heritage Centerdedicated to the preservation of Weeksville.

The Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground is a small burial ground alternatively known as the “Colored Cemetery of Flushing.” A large circular monument notes the burial of 500 to 1,000 people, primarily African Americans, Native Americans, and victims of four major epidemics of cholera and smallpox in the mid-1800s. Acquired by the town of Flushing in 1840 from the Bowne family, the burial ground contains the bodies of slaves and servants of the Flushing elite, as well as members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Death certificates issued in the 1880s confirm that more than half of the buried were children under the age of five. About 62 percent of the buried were African American or Native American.

In 1936, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses decided to build a modern playground on the site of the burial ground. Local activist Mandingo Tshaka halted plans of renovating the cemetery to preserve its history. The Queens Department of Parks commissioned a $50,000 archaeological study in 1996 of the burial ground. In 2004, $2.67 million was allocated to this site, leading to the creation of a historic wall engraved with the names from the only four headstones remaining in 1919.

The Charlie Parker Residence at 151 Avenue B is a Gothic Revival-style rowhouse that served as the home of the legendary saxophonist from 1950 to 1954. Built in 1849, the rowhouse stands four stories tall and faces Tompkins Square Park. Parker lived on the ground floor with his wife Chan Richardson and their three children. By the time he moved, Parker had achieved great fame for helping to develop bebop with Dizzy Gillespie and for releasing standards such as “Ornithology” and “Yardbird Suite.”

He continued performing with jazz groups large and small while living at the home, releasing the album Bird and Diz in 1952. He notably performed at Massey Hall in Toronto in 1953 with jazz greats including Charles Mingus and Max Roach, resulting in the album Jazz at Massey Hall. Though, not all was smooth sailing at the rowhouse; he continued using heroin, and his health started to deteriorate. He spent time in a mental hospital after the death of his daughter in 1954 from cystic fibrosis and pneumonia. Parker died in 1954. In 1992, Avenue B between 7th and 10th Streets was renamed Charlie Parker Place. The Charlie Parker Jazz Festival is held annually at Tompkins Square Park.

St. George’s Episcopal Church, a National Historic Landmark, is located in Stuyvesant Square and is designed in the Early Romanesque Revival style. The original church was located near Trinity Church from 1752, and this new church was constructed from 1846-1856 by Charles Otto Blesch and Leopold Eidlitz, the latter of whom worked on the New York State Capitol Building.

Although not a predominantly African-American church, St. George’s is perhaps best known for having among its congregants Harry Thacker Burleigh, a Black composer and baritone. He was one of the first African-American composers to incorporate spirituals into much of his music. He was accepted to the National Conservatory of Music in New York and was known for his compositions like his versions of the spiritual “Deep River” and songs like “Little Mother of Mine.” Burleigh was hired as a soloist at St. George’s, at the time an all-white church, and the deciding vote in this decision was made by J.P. Morgan. Burleigh would go on to teach composer Antonín Dvořák “Negro melodies” and Native American music, which Dvořák would later incorporate into his famous Symphony From the New World and his American String Quartet.

The Langston Hughes House on East 127th Street in Harlem was the home of Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes where he wrote works like “Montage of a Dream Deferred” and “I Wonder as I Wander.” Built in the Italianate style in 1869, the house is a three-story building added to the NRHP in 1982.

Hughes used the top floor as his workroom for the last 20 years of his life. In 2019, the home received a National Trust for Historic Preservation grant, and today this home is the base of the I, Too, Arts Collective nonprofit, which preserves Hughes’s legacy and supports emerging underrepresented artists.

The Lewis Latimer House in Flushing, a red and white Victorian home, honors Lewis Howard Latimer, an African-American inventor and humanist born to fugitive slaves who lived in the home from 1903 until his death in 1928. Latimer was one of the founders of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Queens, and he was known for his work with figures like Hiram S. Maxim, Thomas Edison and Alexander Graham Bell. The red and white house, which dates back to around 1889, contains a museum dedicated to Latimer’s work and the achievements of other black scientists.

George Latimer, his father, escaped from Virginia to Boston before his subsequent capture and imprisonment. Abolitionists like Frederick Douglass strove to grant George freedom through a publication called “The Latimer Journal, and the North Star.” Growing up in the Antebellum period, Lewis Latimer joined the Union Navy in 1864 and later became an expert draftsman while working at a patent law office. After learning about physics and engineering, Latimer would work with Edison, under whom he invented and patented the carbon filament, which improved the production of the incandescent lightbulb. He also authored “Incandescent Lighting,” the foundation for modern electrical engineering theory. He would also go on to draft drawings for Bell’s invention of the telephone.

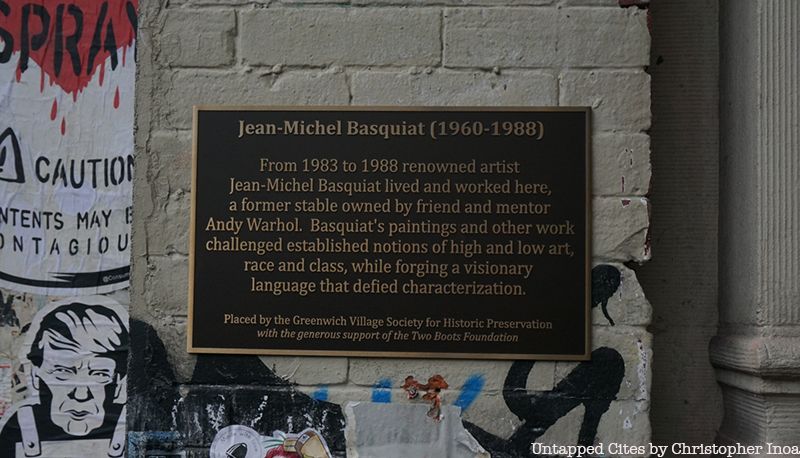

On 57 Great Jones Street in Greenwich Village sits the studio of Jean-Michel Basquiat, an artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent best known for his graffiti art. As part of the graffiti duo SAMO, Basquiat created works like the Irony of Negro Policemen series, and he would often use a crown above his signature. A number of Basquiat’s artworks are still found throughout Lower Manhattan, some of which are protected by preservation societies.

In 2016, Village Preservation unveiled a plaque near the front door of the loft building with Basquiat’s name and a description of his impact on the community, famous for “expressing and juxtaposing conflicting qualities in his work.” The building went on sale in November 2022.

Behind the unassuming exterior of 1467 Bedford Avenue in Crown Heights, Brooklyn is a flourishing event space with myriad historical connections to New York City’s political scene. The former campaign headquarters of Congresswoman and Brooklyn icon Shirley Chisholm, and later the community venue Alpha Space, the building that was built in 1906 has become the new home of Unbossed Media LLC, an initiative working to provide the resources for local artists who haven’t yet had them to get their projects off the ground. Chisholm was the first African American woman to serve in Congress, both the first woman and African American to run for the Oval Office, and the second woman and first African American woman to serve on the House Rules Committee. Chisholm was elected to Congress in 1968 and ran for the presidency four years after. A plaque for Chisholm, created by Alpha Space, was once hanging on the side of the building, but had fallen off due to the wind.

Nearby, the Shirley Chisholm Circle in Brooklyn’s Brower Park is a circular terrace named for her. Chisholm was born in Bedford-Stuyvesant and went on to earn a Master’s Degree in Elementary Education, often teaching her classes outside in Brower Park. As a champion of equal rights, Chisholm would introduce Search for Education, Elevation and Knowledge (SEEK), a program designed to help disadvantaged students enter college. For her work in Congress, she was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama.

Today, a plaque in Brower Park includes her quote “When I die, I want to be remembered as a woman who lived in the 20th century and who dared to be a catalyst of change.” Chisholm is also honored by the newly-created Shirley Chisholm State Park in Spring Creek, Brooklyn, the largest state park in New York City.

In Joseph Rodman Drake Park in Bronx’s Hunts Point neighborhood is an enclosed cemetery and recently discovered slave burial ground. When Drake Park was originally created in 1909, an 18th-century cemetery of wealthy slave-owning families like the Hunts and Leggets were preserved. Yet in 2013, students at Public School 48 analyzed census data and maps to identify a potential spot where the remains of 156 Black and Indian slaves in Hunts Point, per the 1790 Census, ended up.

The students and their teacher Justin Czarka found a black-and-white photograph from 1910 showing several markers resembling headstones, labeled on the back, “Slave burying ground, Hunts Point Road.” The US Department of Agriculture sent scientists to perform soil tests using radar in the cemetery in the summer of 2013, and several areas of the park were determined to have “anthropogenic features” as “likely potential burial sites.” A plaque honoring the burial ground was put up in 2014.

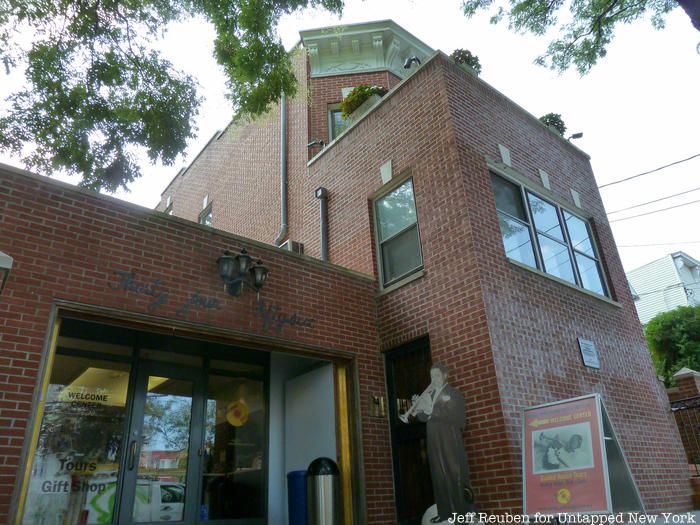

The Louis Armstrong House in Corona, Queens, was where jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong lived with his wife Lucille Wilson from 1943 until his death in 1971. The brick house was designed by architect Robert W. Johnson in 1910, and it now serves as a museum with archives from Armstrong’s writings and concerts. Many gifts that Armstrong received while on tour internationally are also displayed inside the museum, such as ornate paintings.

Originally from New Orleans, Armstrong is perhaps best known for singing “What A Wonderful World” with his characteristic gravelly voice. He pioneered scat singing with songs like “Heebie Jeebies,” and he also famously covered “West End Blues” and “When the Saints Go Marching In.” He led the “Hot Five” and “Hot Seven” ensembles in the 1920s, and he would also appear in films like Hello, Dolly! and High Society.

Addisleigh Park is a historic district in the St. Albans neighborhood of Queens that served as the home of many prominent African-American figures and today is an African American and Jamaican enclave. More than 400 houses were built in the area initially as a segregated area for white people, yet in the 1930s, this policy was reversed and many African-American families began to move into the area.

With easy access to Manhattan, the epicenter of the Swing Era, many African-American jazz musicians moved to the suburban haven of Addisleigh Park. Fats Waller, Count Basie, and Ella Fitzgerald each had homes in the area, as well as Jackie Robinson and W.E.B. DuBois. Many of the original homes have been preserved, and the area was declared a historic district in 2011 by the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission.

St. Philip’s Episcopal Church on West 134th Street is the oldest black Episcopal parish in New York City, founded in 1809 by free African Americans. The church was originally named the Free African Church of St. Philip and was first located in the Five Points neighborhood, before moving north to Harlem. The church’s first rector was Rev. Peter Williams, Jr., an abolitionist who also supported free black emigration to Haiti and served on the executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Many of the church’s members were pioneers in their fields, including many teachers, doctors, restauranteurs, and marine traders. The church would suffer damage in the mid-1800s due to vandalism by whites and by the NYPD during the 1863 Draft Riots. The church moved to Harlem in the early 1900s and was designed by Tandy & Foster, prominent African-American architects, in the Neo-Gothic style. The church included among its parishioners Dr. James McCune Smith, the first African American to hold a medical degree. Among its members were W.E.B. DuBois, Thurgood Marshall, and Langston Hughes.

The infamous Audubon Ballroom at 166th Street is where Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965 while giving a speech. The building was originally built as the William Fox Aubudon Theater in 1912, designed by Thomas Lamb. Shabazz died either en route to or at the Harlem Hospital, across the street.

Today it is owned by Columbia University, which provides space for the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Education Center. Columbia University also preserved the facade of the theater.

The legendary Apollo Theater in Harlem is perhaps one of the best-known sites that have empowered African Americans to showcase their art and break free from oppression. The singer James Brown, who released the album Live at the Apollo, loved the theater so much that his body was brought to the Apollo before his funeral. Music legends like Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Diana Ross & The Supremes, The Jackson 5, Patti LaBelle, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin and many others performed at the Apollo. Additionally, artists like Dave Brubeck and Stan Getz performed at the Apollo, and even The Beatles flocked to the Apollo as soon as they arrived in NYC.

The Apollo Theater was opened in 1914 and was designed by architect George Keister, opening originally as the all-white New Burlesque Theater. It wasn’t until 1934 that it became the Apollo, a hotspot for African American pop culture and music. It became the first theater to allow a mixed-race audience and the first in New York City to hire Blacks for backstage jobs. The year the Apollo opened, Ella Fitzgerald made her singing debut there during Amateur Night, winning a grand $25. Secrets of the Apollo range from its “Good Luck Stump” that entertainers rub before performing to its Wall of Autographs with names like the Obamas, Stevie Wonder, and Michael Jackson.

The Hotel Theresa on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard is an iconic 13-story building in Harlem that served as a center for African-American life in the mid-1900s. Now an office building known as Theresa Towers, the hotel was considered the “Waldorf of Harlem” and was designed by German stockbroker Gustavus Sidenberg in 1913. As a symbol of Black culture in Harlem, the hotel actually only accepted white guests until 1940, when African-American businessman Love B. Woods bought the hotel and ended its policy of racial segregation.

The hotel served as the location of organizations like the Organization of Afro-American Unity, founded by Malcolm X, and the March on Washington Movement, organized by activist A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin. Politicians like Roy Brown, Secretary of Commerce under Bill Clinton, and Charles Rangel, member of the House of Representatives, worked in the hotel. Fidel Castro and his associates famously stayed at the hotel in 1960 for the opening session of the United Nations, renting out 80 rooms. Castro was visited at the hotel by figures like Nikita Khrushchev, Langston Hughes, and Gamal Abdel Nasser. However, the hotel closed in 1967 as the hotel suffered from business due to Harlem’s deterioration, and the building was renovated into office spaces in 1970.

At 935 St. Nicholas Avenue in Washington Heights is the Duke Ellington House, a National Historic Landmark named for the noted African-American composer and jazz pianist who frequently played at the still-active Cotton Club in West Harlem. The Late Gothic Revival style apartment, specifically Apartment 4A, was where Ellington lived from 1939 to 1961, during which time he published the extended jazz work Black, Brown, and Beige.

Ellington was famous for performing Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the ‘A’ Train,” describing a route to Sugar Hill. Other of his noteworthy compositions include “Mood Indigo,” “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” and “In a Sentimental Mood.” His band included musical talents like saxophonist Johnny Hodges and trombonist Juan Tizol, and his album Such Sweet Thunder was actually based on the works of William Shakespeare.

At 5224 Tilden Avenue in East Flatbush, Brooklyn sits the Jackie Robinson House, the home of baseball great Jackie Robinson from 1947 to 1949. The house was constructed around 1912 to 1916, and Robinson would later move to a home in Addisleigh Park, Queens from 1949 to 1955. Robinson was the first African American to play in the MLB, starting at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. At the time, Black baseball players would be relegated to the Negro leagues, yet Robinson would go on to win the Rookie of the Year Award while a resident of the East Flatbush residence. Robinson would win the National League MVP Award in 1949 and would be an All-Star for six consecutive seasons. His uniform number 42 was retired in 1997 across all major league teams. The Jackie Robinson Museum at 75 Varick Street in lower Manhattan was originally scheduled to open this year.

Another notable site related to Robinson are the Ebbets Field Apartments, which were built on the former site of Ebbets Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Ebbets Field was where Robinson played his home games with the Dodgers, and they would go on to win the 1955 World Series. Today, the apartments and a nearby intermediate school are named in honor of the baseball legend with various markers denoting its history, including a home plate plaque.

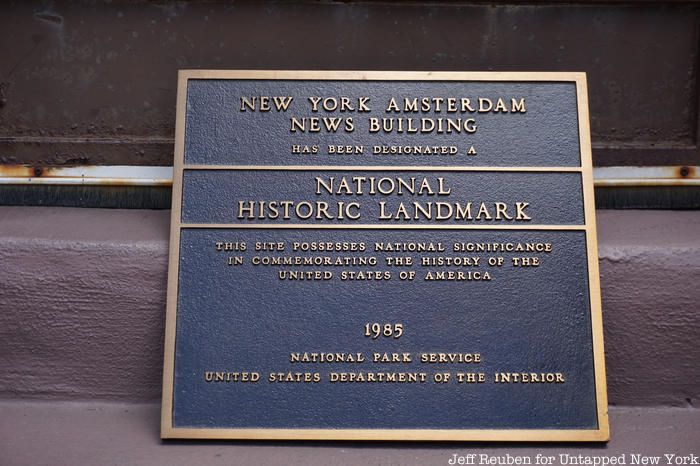

The townhouse at 2293 Adam Clayton Powell Jr Boulevard was the headquarters of the New York Amsterdam News, a weekly African-American newspaper, from 1916 to 1938. The old publishing building on Seventh Avenue in Harlem was built out of brownstone in the Greek Revival style, and it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1976 due to the newspaper’s coverage of major African-American feats as well as issues. It has just recently received its National Historic Landmark Plaque and the building owner allowed us to take a photograph right out of the box.

The Amsterdam News was founded in 1909 and takes its name from its original location one block east of Amsterdam Avenue. James Henry Anderson founded the paper with just a $10 investment, and at the time it was one of only a handful of black-owned newspapers in the United States. The paper originally sold for just 2 cents out of Anderson’s home, yet it was eventually sold to the Powell Savory Corporation, which helped the paper write about both local and national news. The newspaper published the writings of W.E.B. DuBois and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., and it was one of the first publications to publish Malcolm X. Today, the paper is edited by Elinor Tatum, daughter of previous Editor-in-Chief Wilbert Tatum.

The Paul Robeson Residence, formally called 555 Edgecombe Avenue, is one of only a handful of National Historic Landmarks in New York City that commemorates African-American culture. Located in Washington Heights, the skyscraper was originally known as the “Roger Morris” after opening in 1916 in reference to its namesake British Army officer. However, like Hotel Theresa, the building originally started off as restricted only to white tenants, yet this policy would be dropped by the 1940s.

Soon after the neighborhood became predominantly Black, noted African-Americans like musicians Count Basie, Andy Kirk, and Bruce Langhorne moved into the building. Other notable residents include boxer Joe Louis and psychologist Kenneth Clark, who performed the Clark doll experiment with his wife Mamie that was used in Brown v. Board of Education. The building was renamed after resident Paul Robeson, a bass baritone singer and actor who was famously sympathetic towards the Soviet Union and Communism.

Located in the St. Nicholas Historic District of Harlem, the Will Marion Cook House is a townhouse whose namesake African-American musician and composer lived there from 1918 until his death in 1944. The historic district, colloquially known as “Strivers’ Row,” was developed by David H. King, Jr. and was where a number of leaders of the Harlem Renaissance resided.

Cook began his musical career as a student under Antonín Dvořák in 1894 and 1895, and just a few years later he would collaborate with Paul Laurence Dunbar on the musical Clorindy: The Origin of the Cakewalk. Cook founded the New York Syncopated Orchestra, an early jazz group that brought Black musicians to the UK, and he would go on to perform with his orchestra in front of King George V. Cook gained significant fame for his musical In Dahomey, which had 53 full performances. Cook would go on to influence other African-American artists like Duke Ellington and Josephine Baker.

The Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church at 140-148 West 137th Street was constructed at the height of the Harlem Renaissance from 1923 to 1925. Mother Zion Church originally stood at 151 West 136th Street. The new church building on West 137th was designed by George W. Foster Jr., one of the first Black architects registered in the United States.

Services inside the neo-Gothic structure were led by Pastor James W. Brown until 1936 and Civil Rights activist Dr. Benjamin C. Robeson from 1936to 1963. High-profile Harlem residents such as Langston Hughes, W.E.B. Du Bois, Marion Anderson, Roland Hayes, Joe Louis, and Paul Robeson were members of the congregation. Spirituality played a significant role in the literature of the Harlem Renaissance. Today, the church continues to stand as one of the country’s most prominent Black churches and a symbol of Harlem’s religious, cultural, and civil rights history. It was designated a New York City Landmark in 1993.

At 187 West 135th Street in Harlem is the James Weldon Johnson Residence, where its namesake author and civil rights advocate lived from 1925 until his death in 1938. While living in the apartment, Johnson served as General Secretary of the NAACP. The five-story brick building was designed in the Romanesque style and features a curved corner bay. Johnson passed away in a car accident in Maine, and over 2,000 people attended his funeral.

Johnson was a pioneer in many different artistic fields like music, literature, and law. He is perhaps best known for composing the lyrics to “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” which became known as the “Negro National Anthem” and was written to honor Booker T. Washington. Johnson also worked as a songwriter on Broadway and composed an opera called Tolosa with his brother satirizing the U.S. annexation of the Pacific islands. Johnson described his experiences living in post-Reconstruction America in his famed autobiography The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, and he was a prominent Harlem Renaissance figure after publishing the poetry collection God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse. While working with the NAACP, Johnson became the first African-American professor to be hired by New York University, and he also taught literature at Fisk University in Nashville.

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a New York Public Library research library on Malcolm X Boulevard that serves as an archive repository for Black culture worldwide. From poems by Phyllis Wheatley to papers by Malcolm X and Ralph Bunche, the Center is home to everything from manuscripts to rare books to photographs depicting Black culture. The center also houses documents signed by Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture and a recording of a speech given by Jamaican activist Marcus Garvey.

Named after Afro-Puerto Rican scholar Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, the Center often hosts readings, art exhibitions, and workshops, and it is currently directed by Guggenheim Fellow Kevin Young. In the past, the Center has put on influential exhibitions like Malcolm X: the Search for Truth, the controversial Give me your poor…, and “Lest We Forget: The Triumph Over Slavery.” The Schomburg Collection today stands at over 10 million objects written, created, and designed by people of African descent from countries like South Africa, Nigeria, and Trinidad and Tobago.

The Dunbar Apartments is an apartment complex in Harlem on West 149th and West 150th Streets constructed in 1926 by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The complex consists of 511 apartments across six separate buildings and was the first large housing cooperative in the city aimed to provide housing for African Americans. Designed by Andrew J. Thomas, the apartment complex is named after Paul Laurence Dunbar, an African-American poet known for works like “Sympathy,” which inspired Maya Angelou’s memoir I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

The apartments were originally conceived as an experiment in housing reform to provide African Americans a place to live due to Harlem’s housing shortage. The buildings were later converted into rental units after many tenants failed to make payments of $14.50 per room per month. However, the apartments were a significant cultural symbol of the community, housing figures like singer Paul Robeson, poet Countee Cullen, and renowned sociologist W.E.B. DuBois. The buildings were also home to Asa Philip Randolph, an American labor unionist and civil rights activist who founded the first predominantly African-American labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

The Matthew Henson Residence is one of the six apartment buildings of the Dunbar Apartments and is named after an African-American explorer who was arguably the first man to reach the North Pole. Henson lived at Apartment 3F in the building from 1929 until his death in 1955. Henson accompanied the explorer Robert Peary on seven voyages to the Arctic, the first when he was just 25 years old. Expedition records state that Henson was the first of a group of six, including Peary and four Inuit assistants, to reach the North Pole, although these records may be unreliable. He also authored A Negro Explorer at the North Pole and was the first African American to be made a life member of The Explorers Club.

Located in Kew Gardens, Queens is the Ralph Johnson Bunche House, named after the first African American and first person of color to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Bunche helped to found the United Nations and won the Nobel for mediating armistice agreements between Israel and other Middle Eastern countries. He would later research and work on crises around the world in the Sinai, the Congo, and Yemen, and he supervised the ceasefire following the 1960s war between India and Pakistan. For his work with the UN, he was also awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President John F. Kennedy.

The house was built in 1927 in the neo-Tudor style, and Bunche was later sold the property by Jack Sturm in 1952. Bunche moved into the house with his wife and three children and lived there until his death in 1971. The Kew Gardens home was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. Washington D.C. and Los Angeles also have their own homes dedicated to the Nobel laureate, as he lived in each while working at Howard University and while growing up respectively. The property is currently for sale.

Now the site of the Harlem YMCA, the Claude McKay Residence is a National Historic Landmark, named for a leading Harlem Renaissance author who lived in the building from 1941 to 1946. The red-brown brick building was built between 1931 and 1932, and is found just a few blocks north on 135th Street of the Apollo Theatre. Malcolm X supposedly stayed at the building, and the building currently is home to the mural “Evolution of Negro Dance” by Aaron Douglas, an African-American painter and arts educator.

Claude McKay was a Jamaican author perhaps best-known for his poem “If We Must Die,” written in 1919 in response to violence directed towards African Americans during the Red Summer. McKay also wrote novels like Banana Bottom, Home to Harlem, and the treatise Harlem: Negro Metropolis. Unlike many other Harlem Renaissance authors, McKay depicted Harlem rather negatively in his works, writing of its drug use and wealth disparity.

The Countee Cullen branch of the New York Public Library was originally housed in a McKim, Mead, and White-designed Carnegie Library on 135th Street. Open in 1905, that building is now part of the Schomburg Center. The current Countee Cullen Library pictured above was built in 1941 when the library outgrew its original location. The new structure at 104 West 136th Street was built on the site of a former townhouse owned by A’Lelia Walker, daughter of beauty product empire builder Madame C.J. Walker.

A’Lelia’s townhouse was a gathering place for artists and writers of the Harlem Renaissance. As a patron of the arts, she threw lavish parties and eventually started renting our parts of the townhouse for events. This event space was called Walker Studio. In 1927, Walker established a short-lived private membership club called “The Dark Tower.” After Walker’s death in 1931, the property was rented to the City of New York. The townhouse was eventually demolished to make way for the library. Ten years after opening, the library was renamed in honor of famed poet, novelist, and poet Countee Cullen. Cullen’s most famous poetry collections, written during the 1920s, include Color, The Black Christ, and Copper Sun.

The Ivey Delph Apartments in Hamilton Heights is probably unknown to most New Yorkers, but the building was one of the most important projects of Vertner Woodson Tandy, the first African American registered architect in New York State. Designed in the Moderne style in 1948, the apartment was the first large project by and for African Americans in New York that was backed by a Federal Housing Administration mortgage commitment.

Tandy was known for founding an architectural firm with George Washington Foster, an early African-American architect. The apartment was home to Count Basie orchestra trumpeter Buck Clayton and bass player Ted Sturgis. The apartment was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.

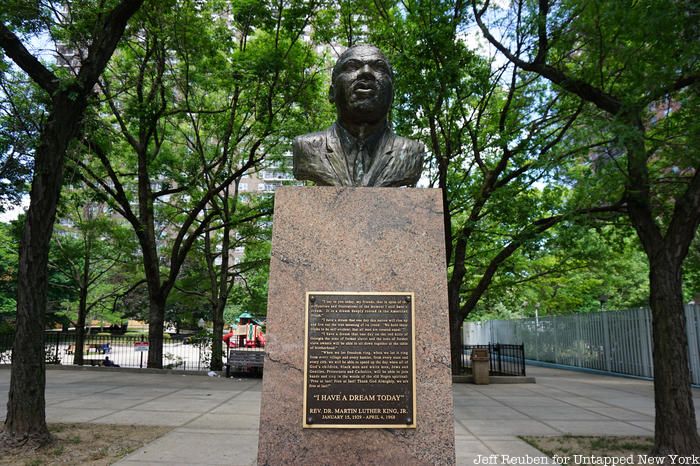

Martin Luther King Jr. is perhaps best known for his actions in cities like Memphis and Washington D.C., but MLK has also had a significant impact on NYC, from leading a march from Central Park to the United Nations over the Vietnam War to giving speeches at Riverside Church in Morningside Heights. For his leadership during the Civil Rights movement, New York City has celebrated him across the city through parks, road names, and monuments.

At the Esplanade Gardens along the Harlem River is a bronze statue of MLK, designed by Stan Sawyer in 1970 with a plaque containing an excerpt of his “I Have a Dream Speech.” Also in Harlem is the Martin Luther King Jr. Park on Lenox Avenue, a few blocks south of the Martin Luther King Jr. Towers that house more than 3,000 residents. In Mott Haven, Bronx, MLK is honored at the Martin Luther King Jr. Triangle, a small green space with benches. Additionally, the New York Times recently listed eight places in New York City that commemorate MLK’s achievements, such as the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, where he delivered a sermon titled “The Death of Evil Upon the Seashore,” and the Harriet Tubman Memorial in Harlem.

1520 Sedgwick Avenue in Morris Heights, Bronx, is an apartment building historically accepted as the birthplace of hip-hop. The popular musical genre supposedly began on August 11, 1973 at a party hosted by DJ Kool Herc, the brother of Jamaican-born graffiti artist, dancer, and DJ Cindy Campbell. People were invited to a “Back to School Jam” at Dr Kool Herc’s “rec room” at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, and supposedly the party was so crowded that it was moved to nearby Cedar Playground.

Cindy rented the recreation room for 25 dollars on August 11, charging 25 cents for females and 50 cents for males to attend. DJ Kool Herc said at a rally that “1520 Sedgwick is the Bethlehem of Hip-Hop culture.” Although hop-hop evolved as a genre over many years, sources acknowledge the apartment as one of the first places where hip-hop culture formed.

The Black Spectrum Theatre is a leading performing arts and media company in Roy Wilkins Park in Jamaica, Queens. The theater was founded in 1970 by Carl Clay as a traveling theatrical troupe, eventually settling into its current spot in 1986 with 325 seats. Black Spectrum has presented over 150 plays, 30 films, and numerous works of music, dance, and performance art, many of which written or performed by Black artists and authors. The theater has received ten AUDELCO Awards and three National Black Theatre Festival Awards for excellence in African-American theater. The theater has put on productions like George Stevens Jr.’s play Thurgood about the life of Thurgood Marshall, spoken word poetry and jazz concerts, and upcoming Zoom panels like “What Do We Want a 21st Century Police Force to Look Like?”

Although much of Manhattan’s Black history is well-documented and preserved, many Black cultural centers in the Bronx have been forgotten; some have been torn down, some have no plaques or landmark status, and some don’t even have recorded addresses. Morrisania in the Bronx is an area with a rich musical history but few historical records or sites. As part of the Bronx African-American History Project, New York City historians and Fordham University faculty have been trying to unearth these sites and stories, and many interviews can be found on the BAAHP website.

According to the New York Times, Morrisania was home to a number of popular nightclubs like Club 45 at 845 Prospect Avenue and Blue Morocco at 1155 Boston Road. Musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, and Nancy Wilson played at these jazz clubs, and today neither original building exists. Morrisania was a major center of Latin music, doo-wop, and hip-hop, yet walking along its streets today, there are few remnants of the times when figures like Dinah Washington illuminated the stage at these now-forgotten clubs. Additionally, many musicians would get their starts at Morris High School, like William Lindsay of The Crickets.

Next check out a Guide to Black-owned Restaurants in NYC and 10 haunts of the Harlem Renaissance

Subscribe to our newsletter