Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

In addition to the thousands of familiar silver passenger subway cars that shuttle straphangers through New York City every day, there is a fleet of specialized work cars that assist workers with routine tasks and repair work throughout the subway system. You may have spotted these yellow and black or blue and silver cars carrying out their duties on late nights or weekends. These all-important work cars perform important tasks such as transporting equipment and supplies through subway tunnels, repairing tracks, and more. Below, we highlight 9 hard-working subway cars that are not meant for passenger travel.

Maybe you will spot one as we ride through the oldest stations, uncover hidden art, and more!

Track inspection was originally carried out manually by inspectors who walked the railroad and visually inspected sections of the track. This task was laborious and required intensive manpower. It was also dangerous. Track geometry cars emerged in the 1920s when manual inspections were no longer practical. Increased rail traffic and faster train car speeds demanded better-maintained tracks. Early track geometry cars used gyroscope technology to record the horizontal and vertical movement of the train and keep track of milestones and stations. A 2013 Federal Transit Administration study found that track geometry cars outperformed human trackwalkers in terms of both accuracy and the total number of track defects discovered.

The New York Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) has conducted human inspections twice a week since 2006, but its fleet of four track-geometry cars runs continual inspections. The specialized train cars feature a variety of lights, sensors, and cameras designed to spot defects and track rail conditions. The cars also measure track gauge, the distance between the two rails. This is an important task since fluctuations in the track gauge can result in train derailments. Engineers onboard the diagnostic train review the data gathered by 30 computers in real-time to spot defects.

The MTA has tried many different methods and machines to keep tracks clean. In 2018, the MTA began operating several new 600-horsepower vacuum trains known as VakTraks. These cars travel at 5 to 10 miles per hour and suck up garbage. The customized trains were built in France at a cost of $7.6 million each. They run on diesel fuel with near zero emissions and are considered the most modern vacuum trains in the world. Various suction hoods on the bottom of the car suck up and then separate dust and garbage from the tracks. A filter car stores up to 14 cubic yards of debris. Unlike older vacuum cars used, which had to clean stations two or three times, the new vacuum train can achieve the same level of cleanliness in just one pass.

Keeping garbage off the tracks is imperative to help combat the growth of the rat population and to avoid track fires. The MTA also tested a Vakmobile in 2017, a miniature mobile unit that was battery-powered. The machine stayed on the platform while workers went onto the tracks with a vacuum hose to collect the garbage. The new VakTrak cars proved more efficient.

From 1951 to 2006, a special armored train moved all the subway and bus fares collected by the New York City transit system to a secret room at 370 Jay Street in Brooklyn. Most money cars were refurbished passenger cars; in 1988, transit authorities converted ten sets of R21 and R22 cars into money trains. Six nights of the week, the money trains would collect revenue from 25 to 40 stations at a time, carrying revenue in one car and 12 collecting agents and a supervisor, all armed and wearing body armor, in another.

The collected money was delivered to the Department of Revenue’s Money Room, hidden inside a 13-story building containing security systems, tunnels, and a secret elevator used to transport money. The disappearance of the subway token and the arrival of the Metrocard made the revenue trains obsolete. The money trains’ final trip took place in January 2006, and the Money Room closed the same day. Revenue collection was relocated to Maspeth, Queens.

Although the majority of NYC’s subway is underground, 40% of tracks are on the ground or elevated overhead. In the winter, the MTA needs to clear snow from the tracks. When a storm hits, subway doors are sprayed with antifreeze, moisture is removed from brake lines to prevent freezing, and special rail shoes are attached to trains.

The MTA also maintains a fleet of snow removal machines to clear subway tracks. This special fleet is made up of Snow Throwers, De-Icer Cars, Jet Blower rail cleaners, and R156 diesel locomotives. The Snow Thrower machines can throw snow up to 200 feet and move 3,300 tons an hour. The Jet Blower, a snow blower with a jet engine mounted on it, reaches 315 degrees Fahrenheit. This powerful car can evaporate and blow snow off of everything in its path. The Rotary Snow Thrower removes snow lying on the tracks while cleaning the contact rail with brushes. De-icer cars scrape the rails with anti-icing fluid.

Perhaps one of the most common work cars you’ll see in the subway is the garbage train. Trash barrels carried on a series of flatbeds were once pulled by retired Redbird subway cars. You can still see these older trains painted yellow on some lines, but now, especially on the lettered lines, you’re more likely to see trash being pulled by silver R32 or R42 subway cars.

The garbage trains run late at night and collect dozens of tons of trash from the subway stations. After a controversial pilot program where trash bins were temporarily removed from 39 subway stations, in 2017 Operation Track Sweep introduced even more trash bins and 27 additional refuse cars to move debris out of the system more quickly. The MTA stated that the new garbage cars were “equipped with special railings to secure and transport wheeled garbage containers that are collected at subway stations.” You can see how workers load and unload the trash bins in this video.

Ballast regulation is an important maintenance task for keeping subway cars running smoothly. Ballast is found below and between track tiles. It serves many purposes including facilitating water drainage, prohibiting plant growth, helping to absorb the load and vibration of the trains, and keeping the tracks in place.

Most subway tracks no longer have ballast, but where it does exist (on outdoor above-ground stretches of track), it needs to be kept in order. Ballast regulator trains help to distribute and even out ballast on the tracks.

Rail grinder trains are used to prolong the life of the rail tracks by grinding out irregularities caused by wear. It also helps to maintain the rail profile or shape. In addition to increasing the longevity of the track, this type of maintenance can also help eliminate noise and vibrations.

Rail grinders usually appear in the signature yellow of other subway work vehicles. According to a 2020 Subway Action Plan, the MTA has three rail grinders in use which covered over 187 miles of track in 2019. Profile grinding can also be done manually with a handheld machine for small areas.

Like many of the work vehicles in the New York City subway system, the pump trains are made up of retired passenger cars. These specialized trains only come out when there is extreme weather. On a usual day, water is pumped out of the subway system by hidden “pump plants” connected to a drainage system.

Pump trains can remove 5,000 gallons of water a minute. There are five pump trains in the MTA’s fleet. In the photo above from November 2012, workers are dealing with flooding in the L train’s tunnel under the East River after Hurricane Sandy.

New Yorkers are used to seeing cranes tower above the streets while building construction is in progress, but cranes are also used underground. The New York City subway employs a telescopic crane that folds up and fits inside the underground subway tunnels.

Crane cars, which again usually sport a bright yellow paint job, are pushed by another subway car. The cranes can move backward and forward along the bed of the car that supports it. They are usually used to aid in replacing stretches of subway tracks.

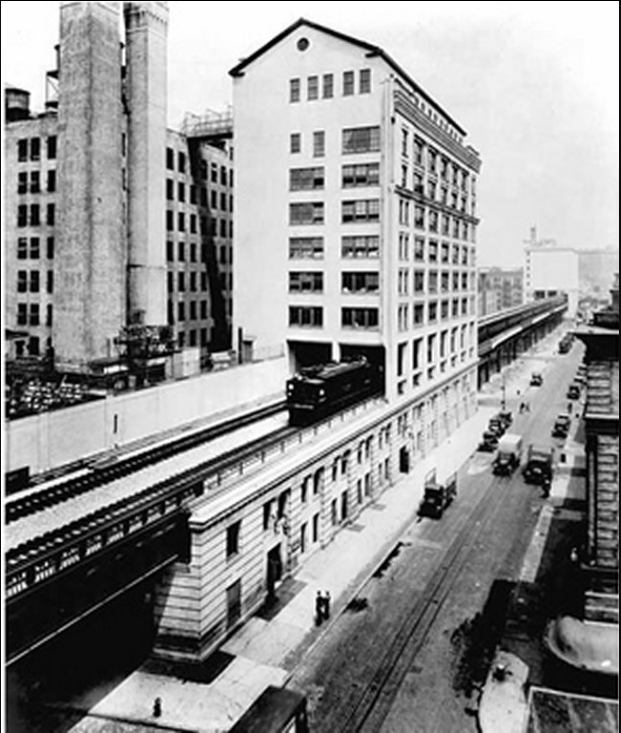

In the mid-1800s, New York Central Railroad freight trains delivered shipments of food to lower Manhattan, but their route along street-level tracks presented a danger to pedestrians. By 1910, more than 540 people had been killed by trains, and 10th Avenue had become known as “Death Avenue.” In response to the rising deaths, the railroad hired men on horseback to protect pedestrians. Until 1941, the “West Side Cowboys” patrolled 10th Avenue while waving red flags to warn passengers of approaching trains.

In 1924, the city’s Transit Commission founded the West Side Improvement project, which ordered the removal of street tracks to protect passengers. The West Side Elevated Line began operating in 1933 to transport millions of tons of meat, dairy, and vegetables to and from warehouses in the Meatpacking District, passing directly through some factory buildings such as the Nabisco Oreo cookie factory, now Chelsea Market. The West Side Elevated Line stopped operating by the 1980s but survives today as the public green space known as the High Line.

Next, check out 20 Secrets of the NYC Subway and See How the LIRR, Subway, and Metro-North Respond to Snow

This article was written by Eliza Browning and Nicole Saraniero

Subscribe to our newsletter