Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Ghost signs are the faded ads that have improbably survived wind, rain, snow, graffiti, and the wrecking ball to provide clues to what life was like decades ago. A surprising number of ghost signs remain in Downtown and Uptown Manhattan, but Brooklyn ghost signs are also abundant. The oldest Brooklyn ghost signs are painted on brick walls. The secret of their survival is the lead paint, banned in 1978, that leached into the brick. Other signs are carved in stone, manufactured in steel, or lit with neon. Some are revealed when a newer sign is removed, like this fish market’s sign in Bushwick pictured above. Use these 10 Brooklyn ghost signs as a starting point; there are many more to discover just by looking up!

French Garment Cleaners opened in Fort Greene in the mid-twentieth century. When Alec Stuart and Celeste Wright opened their indie clothing boutique here in 2006, they preserved the neon sign and even adopted the French Garment Cleaners Co. name.

Stuart and Wright closed the business in 2016. Bird, a designer fashion company with shops throughout Brooklyn, opened in the French Garment Cleaners building later that year. Bird also maintained the dry cleaner’s ghost signage. “Owner Jennifer Mankins said that dwindling margins, rising rents, and direct-to-consumer competition, all compounded by the pandemic, made turning a profit impossible,” reported Business of Fashion. All of Bird’s stores closed in 2021.

A few steps from French Garment Cleaners is what seems to be the remains of a ghost sign of the Scozzari Bakery. It was created for the 2015 film Brooklyn, the story of a young Irishwoman who emigrated to the borough in the early 1950s to find employment.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Pomeroy Trusses had offices in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Newark, New Jersey. “Pomeroy’s Truss and Finger Pad form the best appliance for the relief and cure of Rupture ever invented,” reads an 1870 ad in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

Pomeroy also sold and fitted artificial limbs. One ad promised, “an almost unlimited variety of sockets, joints, and feet insure comfort and satisfaction to each.” Little is mentioned about Pomeroy after 1944 when the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that two men were found guilty of stealing a car from the company. Ephemeral New York reports that the Pomeroy ghost sign in Downtown Brooklyn was revealed in 2014 when an adjacent building was demolished. Note the finger pointing to the elevator entrance.

The New York Daily News was founded in 1919, the first U.S. daily printed in tabloid form. Its slogan from the beginning has been “New York’s Picture Newspaper.” Its stylized camera logo remains today.

The paper’s entire operation, editorial, advertising, and printing, was originally based in Manhattan. Growing circulation led News management to build a printing plant on Pacific Street in Brooklyn in 1927. The plant was obsolete by 1996 and the paper’s printing operations were moved to Jersey City.

About a mile away from the printing plant, a ghost sign with the camera logo remains on the Daily News Brooklyn Garage in Gowanus, an 18,000-square-foot building built about 1900. The cavernous building was used as a distribution center and garage for the tabloid’s delivery trucks until 1993. The garage was sold in 2008 and the Brooklyn Boulders rock-climbing gym opened in 2009. Brooklyn Boulders closed this location in 2022. The building’s facade has since been repainted.

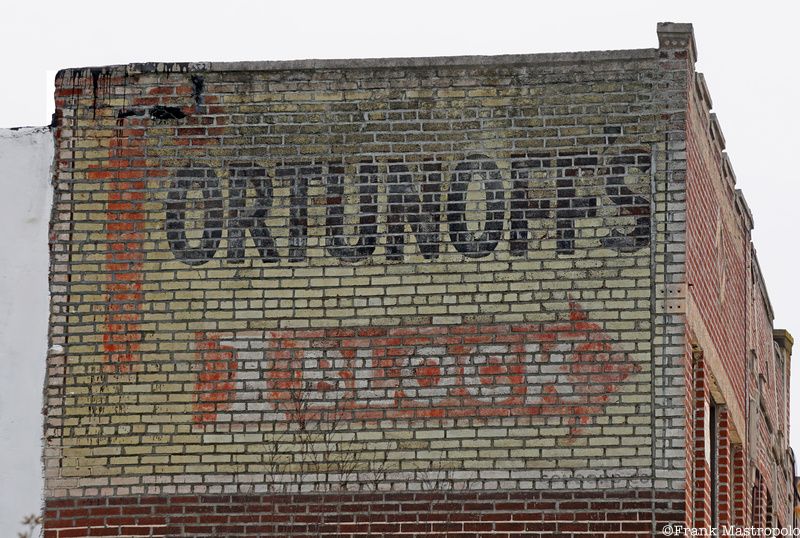

Max and Clara Fortunoff opened their housewares store under the elevated train on Livonia Avenue in 1922. “Here was a store with a real difference,” Fortunoff’s website explains. “A vast selection of quality merchandise, attentive sales clerks, and remarkably low prices.”

The Fortunoffs’ children, Alan, Marjorie, and Lester, later joined the business. As World War II veterans returned home, housewares became such a successful business that Fortunoff’s expanded to eight storefronts along Livonia Avenue in East New York. This ghost sign on Livonia Avenue at Pennsylvania Avenue points the way to the shops.

Alan’s wife Helene introduced jewelry and watches to the business in 1957. “My husband’s interest was limited solely to silver gifts and flatware,” Helene told the New York Times in 2001, “and it was becoming apparent that that wasn’t going to be an important enough business for us. We wanted to offer more luxury products with higher value.” “It was a very poor neighborhood,” Alan told the New York Times in 1989. “The discount aspect of the business was the only way you could operate in that area at that time. If you didn’t offer value, you were out of business immediately.”

The jewelry business was a success but as East New York became one of the borough’s poorest neighborhoods, Fortunoff’s closed all its Brooklyn stores. The company followed its customers to the suburbs and moved to Westbury, Long Island, where it opened a superstore at Roosevelt Field. Further expansion followed, including a flagship store on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, but in 2008 the company went bankrupt. The Fortunoff family reacquired the intellectual property of the company in 2009 and today sells jewelry online. Their backyard furniture line is also sold online and by other retailers.

Little has been written about Magic Touch, an Italian bar and restaurant in Carroll Gardens. The Lost City blog investigated in 2008 and learned that “it had closed in the ’70s sometime (proof that it had been an Olde Brooklyn kinda joint) and that the space was now an artist’s studio.” The blog states that the bar reportedly opened in the 1940s and, according to a local, was a “shady club” where racketeering took place and “girls” could be found. It was “the kind of place where you saw nothing and said nothing,” the source said.

A commenter on the blog disputed those claims, writing, “The establishment featured live music nightly, and pretty good veal and pasta. While it was very popular with the boys, as was Monte’s Venetian Room on Carroll Street and the Diplomat on Third Avenue, it was in no way a place where prostitutes could be found or any nonsense like that would be tolerated.” The double-sided Magic Touch sign on the corner of Hoyt and Third Streets was once lit with neon. It’s hard not to love the top hat and cane logo.

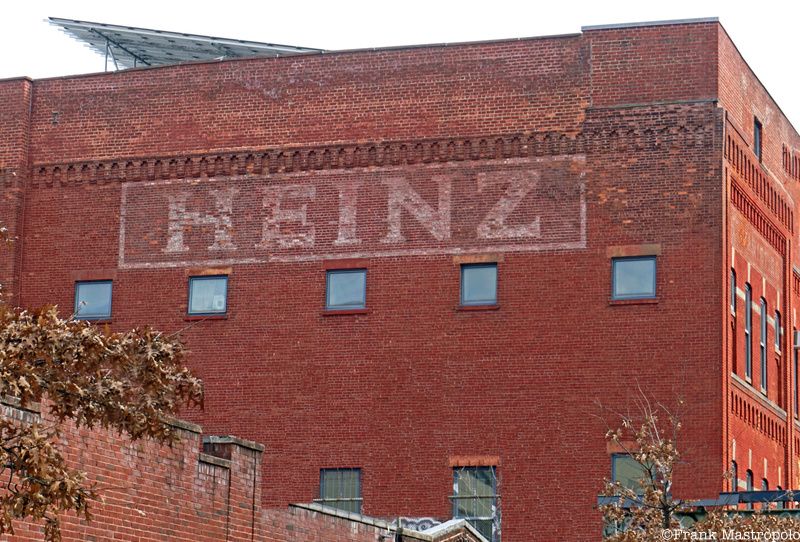

A red brick factory in Crown Heights dominates the view of riders on the elevated Franklin Avenue Shuttle. An assortment of brewing companies operated here beginning in the 1860s. Brands that included Rialto, Frankenbrau, Private Stock, and Extra Bohemian were brewed in huge underground lager vaults at near-freezing temperatures. Nassau Brewing Company was the last of the brewers. Competition from Schaeffer, Rheingold, and other New York breweries forced Nassau to close in 1916.

The H. J. Heinz Company moved into the building in about 1920. The food processing company was founded in Pittsburgh by Henry John Heinz in 1869. Heinz has used its “57 Varieties” slogan since 1896. The slogan remains on the facade of the plant. Heinz moved from the factory in the mid-1930s.

Monti Moving & Storage was the last building-wide tenant at the site. “After this Brooklyn building was renovated and split into 25 workspaces,” reported the New York Times in 2007, “it became home in February to artists, woodworkers, film editors, and architects.”

The Corn Exchange Bank was founded in 1853 at 67 Pearl Street in Manhattan. The bank was an outgrowth of the old Corn Exchange, where merchants met and arranged cereal grain prices with farmers. Corn Exchange merged with many smaller banks in the late 1800s, which gave them offices across Brooklyn. The acquisitions enabled Corn Exchange to inaugurate the branch banking system in New York City in 1899. The Flatbush Avenue branch pictured opened on May 1, 1907.

In 1954, Corn Exchange merged with Chemical Bank to form Chemical Corn Exchange Bank. When Chemical merged with New York Trust in 1959, the words “Corn Exchange” were dropped. Chase Manhattan merged with Chemical in 1995.

“Cheese Shop Closes, Taking Part of Brooklyn With It,” was the headline in the New York Times in 2002 when Latticini Barese shut its doors after more than 75 years in business. The Italian specialty shop — its name means “dairy products from Bari” — opened in Carroll Gardens in 1927. “The neighborhood is changing,” explained the Times, “The neighborhood’s days as a bustling open-air market teeming with fresh fruit stands, bootleggers, and wise guys survive in the memories of Latticini’s aging customers and in faded photographs.”

Joe Balzano and his brother John tried to keep the store going after their father, Joe Sr. retired seven years earlier. Joe Sr. had worked at the salumeria since he was 14. “Old man Joe Balzano, when he was still up and active, rose early every morning to hand make the store’s mozzarella in the back room of the store,” the Lost City blog noted. “It was the best cheese of its kind in the area. The place also had a memorable sausage salad and a peerless sandwich called ‘The Fireman’s Special,’ which included every spicy cured meat and hot pepper you can think of.”

While on the hunt for Brooklyn ghost signs, you might find a few very close together. Across Union Street there is a vintage sign for American Beauty Pasta. “In 1916, the Kansas City Macaroni and Importing Co. merged with the Denver Macaroni Company which used the American Beauty brand name,” notes the company’s website. “In 1947, the company changed its name to American Beauty Macaroni Co. From there, the company’s founder and part-time owner began laying the foundation for what would become one of the country’s leading pasta brands.”

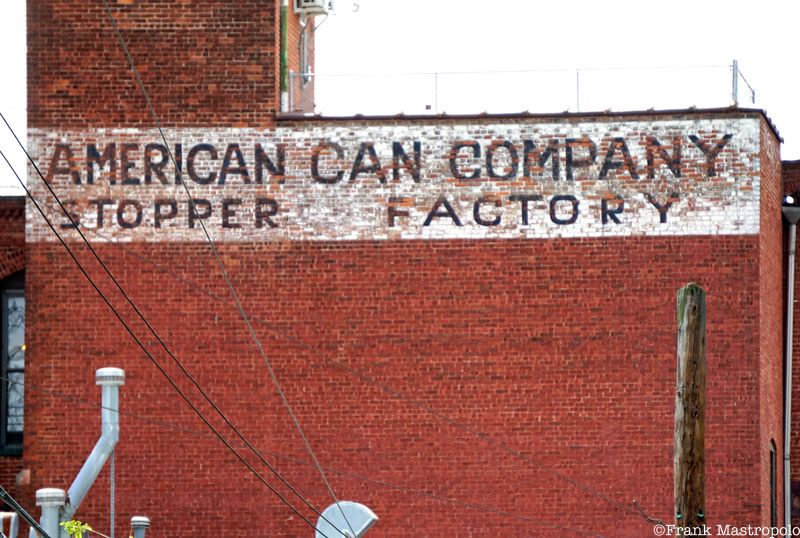

At the turn of the twentieth century, the manufacture of cans was big business in America. Food and toiletry products packed in bottles and cans of the era required air-tight stoppers that could be removed and applied over and over. Beginning in 1886 notes Eating in Translation, the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company bottled its popular petroleum jelly, Vaseline, at this building in Red Hook. The American Stopper Company moved to the plant in 1903. American Stopper was acquired by the American Can Company in 1915. Two floors were added to Chesebrough’s two-story plant, which displays the company’s ghost sign.

The American Can Company, a manufacturer of tin cans, was founded in 1901. American Can left the packaging industry after many mergers and in 1987 was renamed Primerica, a financial conglomerate. Today, apartments and small businesses occupy the complex.

The Kranich Soap Company was founded in 1921 by Herbert Kranich as the Kranich Chemical Co. Kranich later merged with Specification Soap to form the Kranich & Specification Soap Co. The new company opened at this Brooklyn location in 1924. The name was changed to Kranich Soap Co. “in response to requests from the trade for a simpler title,” notes American Perfumer & Essential Oil Review in 1926.

Kranich manufactured potash soap, also known as potassium soap, a soft soap made from the lye leached from wood ashes. A 1922 ad in American Perfumer lists toilet soap, shampoo, and shaving cream among its products. The factory in Red Hook closed in 1963.

For more NYC history, check out the author’s books on the legendary East Village concert hall Fillmore East and Manhattan’s rock n’ roll sites, shows, and songs. Next, check out Ghost Signs of Uptown Manhattan.

Subscribe to our newsletter