Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Uncover the details behind successful and attempted art heists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC!

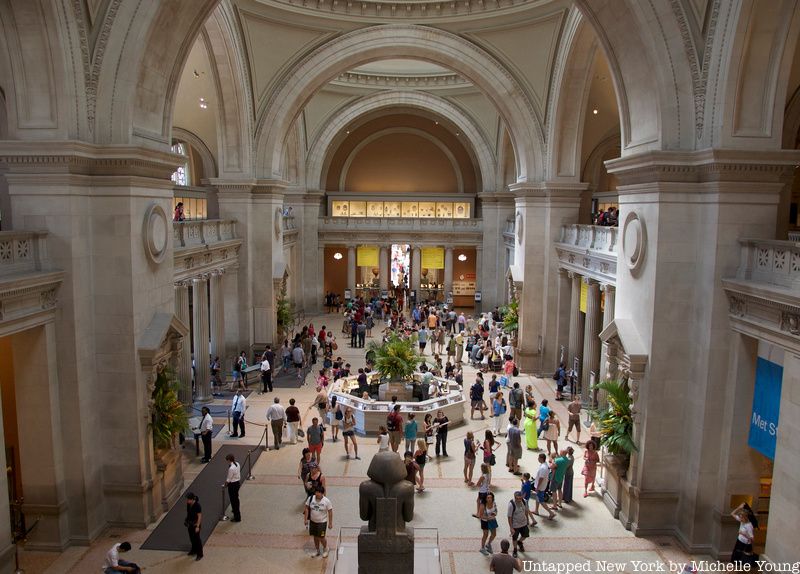

It’s not easy to steal from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. There hasn’t been a major robbery at the museum in 40 years. Thanks to its guard force of over 500 people and its hi-tech security systems, the more than 1 million objects held within the museum are safe and sound. It was a bit of a different story before the 1990s.

Since the Museum’s founding in 1870, there have been a handful of major museum robberies that made headlines. Headlines from recent years have been concerned with artifacts that were stolen before making it into the museum collection, highlighting efforts of law enforcement and museum staff to root out improperly acquired artifacts and hasten repatriation. Here, we take a look back at 10 successful and attempted art heists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City’s world-famous art institution.

One of the earliest Metropolitan Museum of Art robberies took place in September 1887. Less than a decade earlier, the museum had moved into a new building designed by Calvert Vaux and Jacob Wrey Mould at its current site in Central Park. It was the first of many buildings and additions that would be constructed to create the sprawling museum we see today. The artifacts stolen were a pair of solid gold bracelets. The bracelets were part of the Kurium collection, an array of artifacts dug up in Cyprus by General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, the Met’s first director.

A New-York Tribune article from just a few days after the robbery describes the bracelets as “solid gold, about four inches in diameter, richly carved and studded with all manner of precious gems.” To get the bracelets, estimated to be worth $1,000 at the time, the robbers simply pried open the case. The bracelets were stolen in broad daylight while museum guards were on duty. It is believed that the robbers made away with the bracelets sometime between 10 am when the museum custodian cleaned and dusted all of the cases, and 11 am when two museum visitors reported the broken case. The bracelets were never recovered, but replicas based on museum records were created for the museum by Tiffany & Co.

Multiple Dates at 10:30 am ET: Encounter breathtaking masterpieces and overlooked treasures whose stories span continents, cultures, and millennia!

In April 1910, a newly dug-up bronze statue of the Egyptian goddess Neith was stolen from her perch on the second floor of the museum. It was only a few days later when she was found in a pawn shop window in the Bowery. According to an article from April 24th, 1910 in the New York Times, the pawnbroker had no idea he was handling a 2,500-year-old treasure, he thought “it might make a good paperweight” and would be a nice knick-knack to decorate the window with. He gave the “poorly dressed man” who brought it in 50 cents. The true value of the statue at the time was $1,500.

Once news of the theft hit the newspapers, the pawnbroker realized he had stolen goods in his possession. When the police came into his shop, the pawnbroker knew exactly what they were there for. When the statue was returned, its left hand was missing, which was holding a staff was missing. The statue is now on view in the Egyptian wing.

The robbery of five 17th-century paintings committed on July 18 1927 was likely an inside job. The miniatures were only “three inches square, hand-painted on ivory and framed in gold set with diamonds,” according to the New York Times. They were estimated to be worth between $5,000 to $10,000.

The usual nightwatchman who would have been on duty in the gallery the paintings were stolen from was sick that evening and there was no one to fill his position. “No marks were visible on the showcase, leading to the belief that it had been opened by use of a skeleton key,” reported the Times. Two frames from the stolen portraits showed up days later in a pawn shop. The paintings themselves were cut out and never recovered.

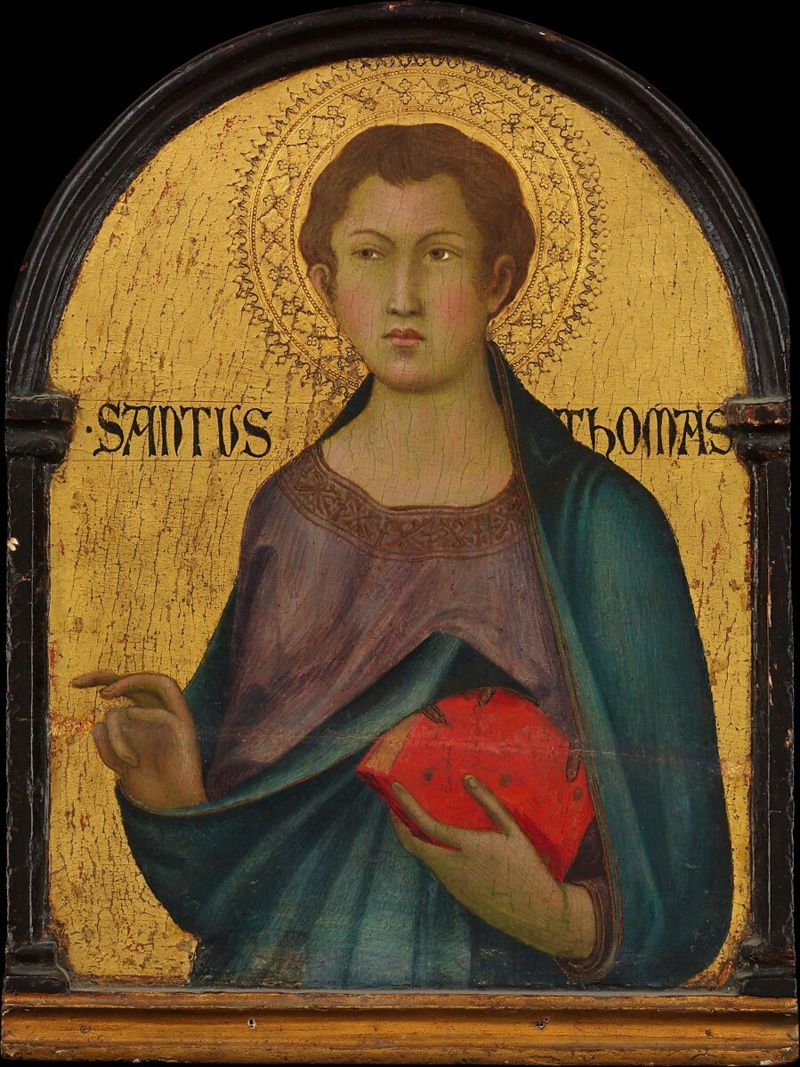

Theives didn’t strike again until March 1944 when a 14th-century painting of St. Thomas was snatched from a gallery of early Italian Renaissance paintings. Attributed to the workshop of Simone Martini, the painting was valued at $3,000 to $5,000 at the time of the robbery. It was one in a series of six painted wooden panels. For nearly five years, the fate of the painting was unknown. Then, it showed up in the mail.

In January 1949 a package wrapped in brown paper arrived at the museum. Once unwrapped, the stolen painting was discovered covered in several layers of tissue paper. The package didn’t have a name on it but was postmarked from Tremont Station in the Bronx. The return address on the package didn’t actually exist. Due to the poor and unprotective wrapping, the wooden painting was cracked in transit, but the damage wasn’t substantial. The item is not currently on view as of this writing.

In 1953, an opportunistic thief stole an 18th-century porcelain statuette of English statesman William Pitt the Elder while the guards switched posts. The statuette was dated to 1775 and was created by the esteemed Chelsea-Derby porcelain factory. The piece stood on a mantel in a Philadelphia room on the second floor of the American Wing.

The statue, which stood just under a foot tall, was securely anchored to the mantel, but the thief ripped it right off. Museum officials told The New York Times that the statuette’s value was “nominal,” as many similar statuettes had been made in the 18th century.

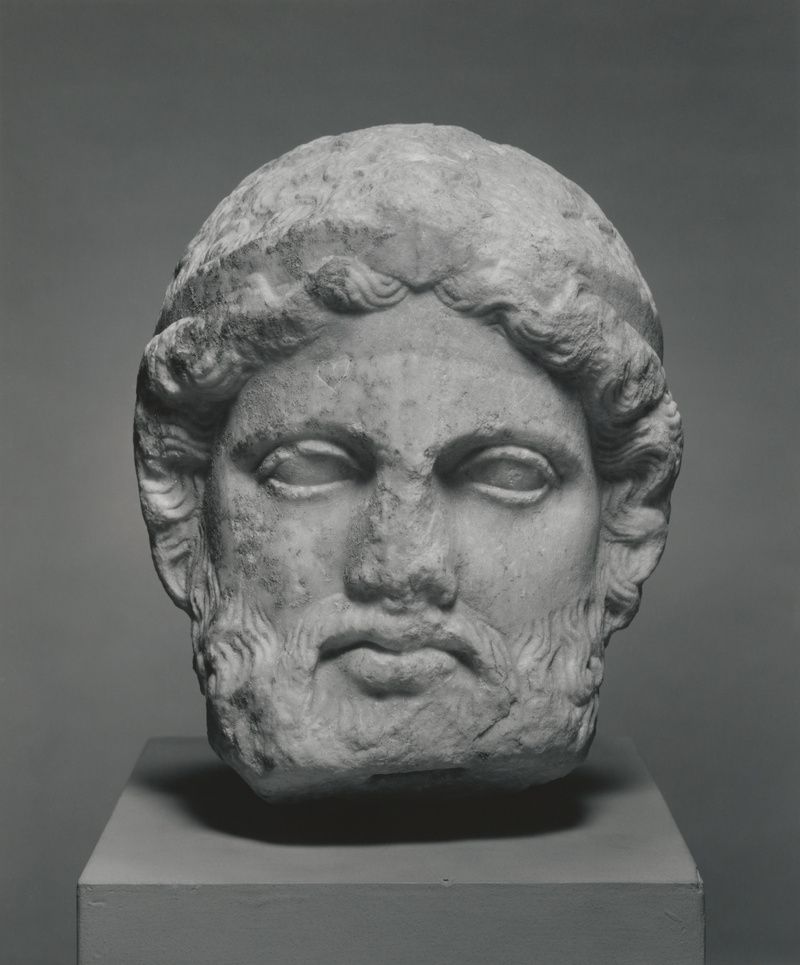

Perhaps the most bizarre of all the Metropolitan Museum of Art robberies occurred the week of Valentine’s Day 1979. For just ten minutes, from 3:15 PM to 3:25 PM, a gallery of Cypriot art was left unsupervised as the guards switched. In that short time, a 2,500-year-old sculpture – a marble head of Hermes – was swiped from its wooden pedestal. Just a few days later, an anonymous call was made to security at Rockefeller Center.

The caller told the security officer who picked up that the stolen Met sculpture would be found inside locker No. 5514 at Grand Central Terminal. Within minutes of the call, detectives descended on the terminal and pried open the locker. The head was indeed inside. When the sculpture was taken from the museum, it had a small heart-shaped mark above its left eye. When it was returned, it had a new matching heart-shaped mark above its right eye. Was the robbery a Valentine’s Day gift gone wrong? No one was ever caught for the crime.

Just a year after the marble head was stolen, a couple of teenagers made off with an ancient Egyptian ring from the time of Ramses VI. Before they could be caught, they sold the ring to a Manhattan jeweler for $10,000. That jeweler, Bernard Yervanian, and his employee Vincent Vella then attempted to broker a deal with the museum to sell the stolen ring back.

Yervanian got in touch with the museum and let them know that he could return the ring, for a fee of $80,000. He would act as the museum’s “authorized representative” and asked that no police be present when he exchanged the ring for his “commission,” according to the New York Times. Upon the appointed meeting time for the handoff, Yervanian’s employee Vella set out to meet with museum officials but was instead met by the police. Yervanian was in cuffs soon after and the 16-year-old who originally stole the ring, along with an accomplice, was also tracked down.

Another inside job was perpetrated in 1981 when a museum employee stole six small ancient Irish items made of gold. The lot was estimated to be valued at over $180,000.

The items stolen included two 2nd-century B.C. Celtic coins and gold clothing fasteners from the eighth century B.C.. The museum employee was charged with grand larceny after the coins were traced through a tip from a dealer. Only a few of the items were found and returned.

Armed with two screwdrivers, a hammer, and two flashlights, Lorith W. Stunbaugh walked into the Metropolitan Museum of Art determined to leave with a pricey souvenir. Stunbaugh entered the museum on a Saturday night in December 1946 with other attendees of a special choral concert, officials told the New York Times. During the performance, he snuck away to the Near East exhibit on the second floor.

Once there, he found a 4 by 5-foot 17th-century Turkish prayer rug hanging from the wall by copper wires. He ripped the rug off the wall and stuck it under his coat. Thanks to the observant eye of veteran guard Dan Donovan, Stunbaugh was caught before he could leave the premises.

In April 1966, a clumsy thief attempted to steal a portrait of “Lady Mulgrave” from a second-floor gallery of European paintings. The criminal was spotted by a museum guard as he worked to free the painting. The guard shouted at the thief, who bolted away with the painting. In the chase, the painting was dropped, but the attempted robber got away. Luckily the painting, first attributed to Thomas Gainsborough and then to his nephew Gainsborough Dupont, was unharmed. Despite a massive search, the perpetrator wasn’t caught.

Multiple Dates at 10:30 am ET: Encounter breathtaking masterpieces and overlooked treasures whose stories span continents, cultures, and millennia!

Next, check out Top 5 Notorious NYC Crime Scenes and The Epic Jewel Heist at NYC’s American Museum of Natural History

Subscribe to our newsletter