Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

New York City has always been a hot spot for luxury hotels, which compete with each other for the latest amenities, the most unique architecture, and more. The cycle of construction, demolition, and rebirth is as old as the city itself. Apart from those that have been preserved by landmark designations, many of what were once New York’s grandest hotels have been lost to history. As a look back, here are ten notable lost hotels of New York City that are no longer standing.

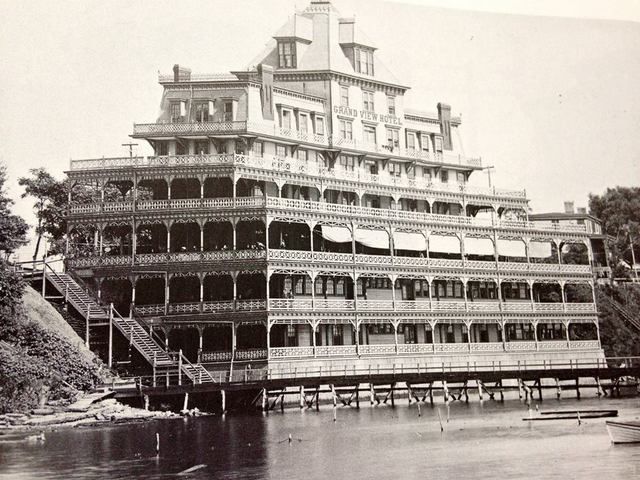

The Grand View Hotel once stood at Fort Hamilton in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn overlooking the Narrows and Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island. The hotel was built in 1886 for $122,000, with a capacity of 1,000 guests. Built onto a bluff, the water side of the hotel had ten stories, and the street side had seven, with wraparound open-air balconies much like a Mississippi show boat. As was the fashion of the time, some New Yorkers spent the summer months there on a long-term basis. It was built by the Brooklyn City Railroad, and purchased in 1891 by Adolph Ruehl for just $80,000, because as The New York Times reported, it had “been a failure.” But just two years later in 1893, the hotel went up in flames.

A New York Times article reported that the fire was caused by an explosion in the basement where an “amateur photographer’s outfit of chemicals” were kept. Ruehl told the newspaper that had the Hamilton Fire Engine Company arrived in a timely matter, the building could have been saved, but alas the officers were “at their annual ball at New Utrecht-Town Hall, far away.” The entire structure burned to its foundations. Further compounding the unfortunate situation, Ruehl had allowed the insurance policy on the property to lapse, and could only hope that the Brooklyn Railroad City company’s $45,000 insurance would be enough to rebuild. The Grand View was just one of many waterfront, lost hotels in New York City that once dotted the Brooklyn coastline.

From 1885 until 1896, Coney Island had the most fantastical of all the New York City lost hotels: the Elephant Hotel (also called the “Elephantine Colossus” or “Elephant Colossus”). It was 200-feet tall with a gilded crescent and stood proudly and prominently on Surf Avenue and West 12th street. James Lafferty designed the 12-story building with 31 rooms, even calling it the “Eighth Wonder of the World.”

Inside the elephant was a concert hall, events bazaar, museum, observatory, cigar store, and diorama. Its legs were spiral staircases leading to higher rooms and its eyes were telescopes. But New Yorkers tired of the gimmick and according to the New York Historical Society, it then became more of an “Elephant Brothel.” But even the prostitutes moved on to greener pastures, and the Elephant Colossus was pretty empty by the time a fire destroyed it in 1896. You can read more about some of Coney Island’s other bizarre attractions here.

Ever wonder about the more exotic street names in Southern Brooklyn? Oriental Boulevard on Manhattan Beach is one of this handful of colorfully named (perhaps culturally insensitive from today’s perspective) streets slipped into otherwise peaceful residential areas. Walking down Oriental today lends itself to strikingly ordinary views of private residences and bits of high school property, but its name reveals what the neighborhood used to be: a hub for luxe beach resorts.

Imagine a strand of resort hotels nestled in white-sand beaches. Posh, scented with orange blossoms, perhaps the sort of place Dick and Nicole Diver would vacation. Now imagine it in Brooklyn. Such a place existed just over a century ago, and the Oriental Hotel in Manhattan Beach was the crown jewel of southern Brooklyn resorts. Manhattan Beach itself was conjured up by Long Island Railroad President Austin Corbin, who coined the name in hopes to lure Manhattanites to his new resort destination. His role within the LIRR ensured that a new train line was built to Manhattan Beach.

The Oriental Hotel was not the only grand hotel in the area. The first to be built was the Manhattan Beach Hotel, officially opened by President Ulysses S. Grant himself on July 4th, 1877. It was a popular destination for the elite of New York City, and many posh private clubs would operate out of the hotel during the summer. At the Oriental Hotel, the wealthiest of New York’s residents would book extended stays for the summer.

The Brighton Beach hotel, built in 1878 (literally picked up and moved 175 yards inland by six locomotives in 1888 to counter erosion), could accommodate up to 5,000 guests but never had the success of the others – it was deemed too close to the mass entertainment at Coney Island. Gradually, the properties along the Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach coast would be sold off for residential development.

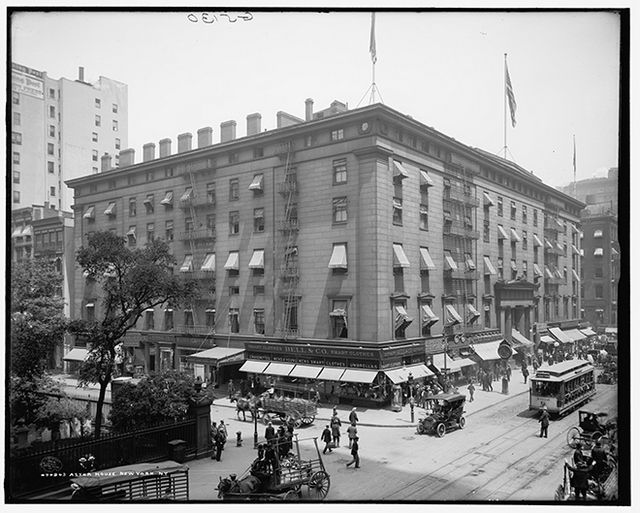

Moving back to Manhattan, Astor House was the first luxury hotel in New York City, situated on Broadway between Barclay and Vesey Street across from City Hall. It opened in 1836 and had running water before the Croton Aqueduct was completed in 1842, and its distinguished guests included Abraham Lincoln, who gave a speech there before his presidential election.

Built on the former site of one of John Jacob Astor’s homes, the granite-covered hotel boasted more than 300 guest rooms that went around an interior courtyard. In 1913, the hotel was demolished in phases to accommodate the construction of the subway, one of many lost hotels of New York City that were related to the Astors.

The Pabst Hotel opened in 1899 at what is now One Times Square—close to the Pabst brewery at 49th Street. The hotel, according to the New York Times, had five bedrooms on each of the upper floors, and in “early 1900 the owners added a conservatory on top of the portico, an extension of the Empire-style restaurant on the second floor.”

The construction of the IRT subway went through the basement of the hotel and in 1902, owner Gustave Pabst, vice president of the brewing company, sold it to Adolph S. Ochs, publisher of The New York Times. The New York Times Building was built on the same triangular plot, and still stands today, one of the emptiest but most profitable buildings in Midtown. It is also where the New Year’s Eve Ball is stored. This is just one of the lost hotels in New York City that was owned by the Pabst company.

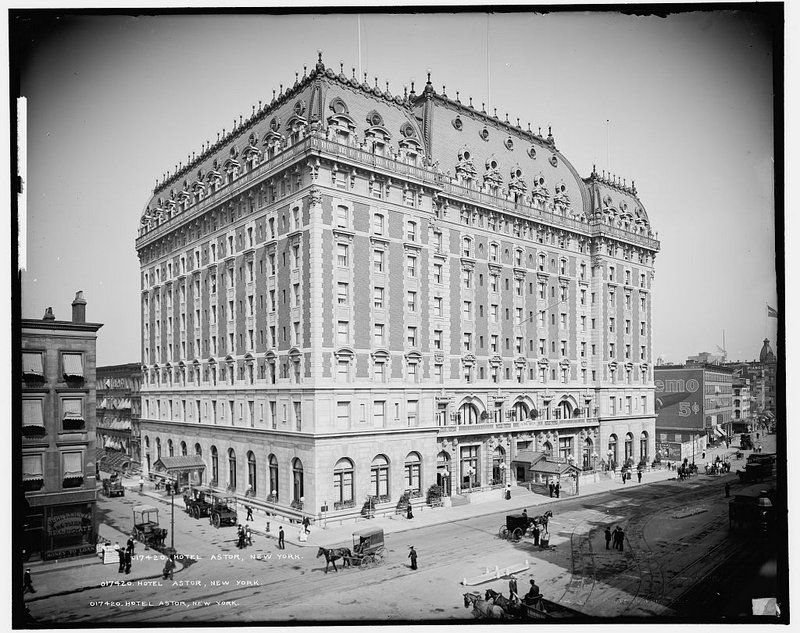

The Hotel Astor was the first of the grand hotels to arrive to Times Square, conceived of by William Waldorf as the next iteration of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The French-inspired building had a green copper mansard roof, a Louis XV style Rococo ballroom and a rooftop garden for entertainment, drinking and dining. The hotel was designed by New York architect Charles W. Clinton and Connecticut architect William H. Russell and built atop former farmland.

After changing ownership several times, the Hotel Astor was demolished in 1967. It lives on as an illustration on Dr. Brown’s Soda cans. Today, the site is home to 1 Astor Plaza, which contains MTV Studios, Viacom, and the Minskoff Theatre. Next door to the Hotel Astor was the Astor Theatre, which was demolished in 1982 and replaced by the Marriott Marquis hotel.

Today’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue is full of its own rich history and secrets, but the original hotel was on the site of what is now the Empire State Building. In 1893, William Waldorf Astor hired renowned architect Henry Hardenbergh, who would later design The Dakota apartments, to build a 13-story grand hotel on the site of what was his family mansion. At the time, it was the largest and most luxurious hotel in the world, with 450 rooms. He then hired the talented George C. Boldt to act as General Manager. Mr. Bolt, with his reputation for the highest levels of service, quickly brought to the Waldorf Hotel a reputation as a premiere hotel–the first to offer private bathrooms, room service and electricity throughout.

Mansions of Fifth Avenue Tour

Learn about the lost mansions of the Astor family on our upcoming walking tour of the Gilded Age Mansions of 5th Avenue!

Meanwhile, John Jacob Astor IV owned the other end of the block. Four years after the construction of the Waldorf, John Jacob built a 17-story hotel within feet of the Waldorf, using the same architect. His intention was to name the hotel The Schermerhon after his mother and he approached George Boldt with the idea of managing his hotel, since George worked just feet away for his cousin. But George had a problem with the hotel name and said that he would only agree to manage it if it had a more appealing and less difficult name. John Jacob came back with the name “The Astor,” named after the fur-trapping colony in Oregon where his family was originally from.

In time–and having good business sense–it was decided that the hotels should be physically joined together by a long hallway. The combined hotels, opening in 1897, became the largest hotel in the world. The sinking of The Titanic took the life of John Jacob Astor IV in 1912, and William died of a heart attack in 1919. The land where the grand hotel sat was sold in 1928 to a developer, who demolished the building and erected the Empire State Building.

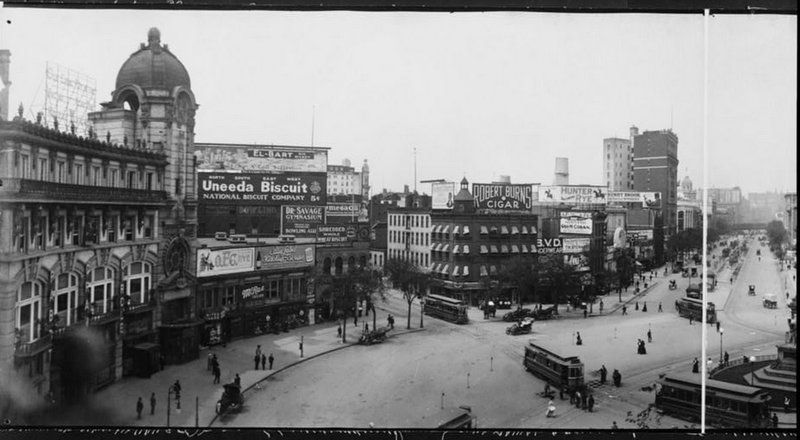

None of the Victorian-style buildings that once defined Columbus Circle survive today. Another of Pabst’s lost New York City hotels was among them, the Pabst Grand Circle Hotel. The Hotel and the Majestic Theatre were built for the Pabst Brewing Company in 1903. The sign in the above photo advertises Majestic Theatre’s production of “Babes in Toyland.”

The complex was demolished in 1954 and replaced by the New York Coliseum, a convention center that was in turn demolished in 2000. In the construction of the Coliseum, 59th Street was eliminated between Broadway and Columbus Avenue, a street pattern that continues until this day. Today, this is the site of the Time Warner Center.

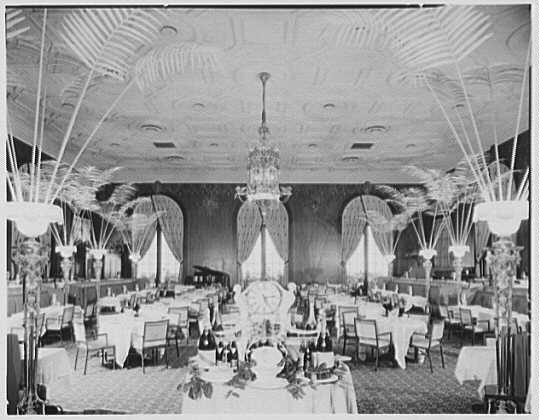

The original plans for Grand Central Terminal called for an entire city, dubbed Terminal City, to accompany the now landmarked train station. The Biltmore, located on Madison Avenue between 43rd and 44th Street, was the brainchild of Gustav Baumann and was the fourth grand New York City hotel to be designed by Warren & Wetmore, the architects of Grand Central. Its design ensured that at twenty-six stories it still maintained a harmonious relationship with the rest of Terminal City. A palm court, grand ballroom, Italian garden, and private arrival station at Grand Central ensured that the Biltmore would be in a class of its own. Its name lured the likes of Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald to honeymoon there. Fitzgerald and J.D. Salinger incorporated the hotel into their stories.

In August 1981, the Biltmore was gutted and from its steel frame was transformed into Bank of America Plaza, or 335 Madison Avenue. A small reminder of the building’s past is still present at 335 Madison Avenue. The clock that once hung at the entrance to the Biltmore’s palm court and its piano can still be found in the lobby of 335 Madison Avenue.

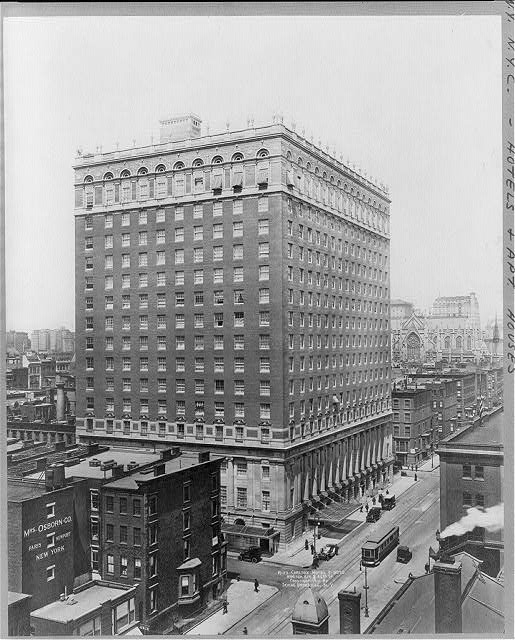

The original Ritz-Carlton Hotel, opened in 1911 at Madison Avenue and 46th Street. Also designed by Warren & Wetmore, is was another lost New York City hotel of Terminal City. In addition to its luxurious amenities, ballrooms rooms and cuisine (French chef Louis Diat is said to have invented Vichyssoise soup there, though others have made the same claim), it was apparently notable also for its engineering. A magazine on engineering from 1913 proclaimed that “hotel ventilation has become a fine art,” with a three page feature on the system at the Ritz-Carlton New York.

The Biltmore was demolished in 1951 to make way for an office building. A new Ritz-Carlton would not operate again in New York City until 1982 on Central Park South.

Next, discover the Secrets of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel and the Secrets of the Plaza Hotel.

Subscribe to our newsletter