Play Vintage Games at the Red Hook Pinball Museum

Explore the museum's collection of meticulously restored vintage machines from as early as the 1800s!

Around the turn of the 20th century, thousands of Eastern European Jews immigrated to the United States and settled on the Lower East Side. Many moved into tenement buildings and took up employment at sweatshops, factories, and local stores. Many of these recent immigrants, struggled to survive on low wages and poor living conditions, leading many to eventually move away from the area. As the area became more gentrified and built up, many sites related to Jewish history on the Lower East Side began to disappear.

“I think one of the fascinating things about the Lower East Side is that it’s been estimated that there were probably over 600 houses of worship that existed between 1880 and 1924 around there,” said Richard Soden, a longtime Lower East Side resident, and Museum at Eldridge Street docent who leads Untapped New York’s tours of the Secrets of the Lower East Side. “There was an overabundance of people on the Lower East Side at the time. It’s been recorded and documented that the Lower East Side as we define it in those days probably had the largest population [of Jews] in the world during that period of time. About two-and-a-half-million left Eastern Europe, and about 2 million made their way to the Lower East Side.”

Many Jewish people would frequent 113 Allen Street, which housed public baths for those who did not have baths or showers in their apartments. Many shopped at Ridley’s Department Store on Grand Street and bought from pushcarts on Hester Street. Restaurants like Yonah Schimmel Knish Bakery and Katz’s Deli opened in the early 1900s and quickly became go-to spots for the local population. One of the largest tenement buildings they moved into was 14-16 Orchard Street, which seemed to combine two buildings into one and featured an elaborate roof design. Even the Williamsburg and Manhattan bridges played a major role in the lives of Jewish immigrants, enabling people to leave the area and spread out; the former of which was even known as “Jew Bridge” because so many people would use the bridge to come back on Saturdays from their houses of worship.

With assistance from Soden, here are 10 Jewish history sites on the Lower East Side, from modern-day museums and synagogues to abandoned buildings whose connection to Judaism is not as obvious. Be sure to join us for our Secrets of the Lower East Side tour and tasting!

The Forward, previously known as The Jewish Daily Forward, was founded in 1897 as a Yiddish-language daily newspaper with a socialist spin. It was edited by Abraham Cahan, who co-founded it with Louis Miller, for 43 years. After several years working with radical revolutionary groups, Cahan fled the Russian Empire and was among the first large wave of Eastern European Jewish immigrants who came to America just prior to the 20th century. At its peak circulation around 15 years after its founding, The Forward erected a ten-story building at 175 Broadway designed by architect George Boehm. The building competed with the Jarmulowsky Bank Building for the title of “tallest building on the Lower East Side.”

The building was considered the first skyscraper of the Lower East Side, which drew criticism from some prominent figures who believed that the building too strongly associated itself with capitalism. Others, though, believed that the building was a protective symbol of the working class, towering over surrounding tenements and sweatshops to signify what could happen with hard work and commitment to religion. The building was embellished with marble columns and panels, as well as stained glass windows. The facade includes bas relief portraits of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and Ferdinand Lassalle, who founded the first mass German labor party. The building was converted into condominiums in the 1990s, and The Forward moved its headquarters to East 33rd Street and then to the Financial District.

The Jarmulowsky Bank Building is a 12-story building that formerly housed the Jarmulowsky Bank at Canal Street and Orchard Street. The building is named after Sender Jarmulowsky, who established his bank in 1873. Jarmulowsky was born in 1841 in Grajewo, Russia — now a part of Poland. He was orphaned and raised by the Rabbi of Werblow, and he was sent to an elite Talmudic academy called the Volozhin Yeshiva. He soon after married Rebecca Markels, the daughter of a wealthy Polish merchant, and he was on track to become a renowned scholar.

However, Jarmulowsky had other plans. In 1868, he moved his family to Hamburg, Germany, purchasing steamship tickets and selling them to German and East European Jews who hoped to immigrate to America. Jarmulowsky’s anticipation of hundreds of people going to America allowed him to outcompete steamship companies, leading him to move to New York and open up a bank — where he made his wife a full partner. The bank, at 54 Canal Street, was considered a “bank” for immigrants that provided loans, deposits and ticket sales. The bank was open all day on Sunday, which allowed Sabbath-observant Jews to take care of their financial needs on the weekend. The bank was reputed to serve more than 60,000 depositors and survived bank runs in 1886, 1890, 1893 and 1901. When World War I broke out just two years after the bank building was completed, German investors withdrew funds to send to relatives abroad, and the bank subsequently failed.

The Beaux-Arts façade of the building has been landmarked. The building is faced with limestone on the lower section and terra cotta at its top section. Until 1990, the building featured a rooftop Greek tempietto that rose 50 feet to a dome ringed by eagles, and a recreation of this was unveiled 30 years later. The exterior decorative banding “S. Jarmulowsky” will remain to honor the man who founded the successful bank, the Eldridge Street Synagogue with a few other successful businessmen, and the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America. It is now a boutique hotel called Nine Orchard.

Once the most densely populated district in the world, the Lower East Side of Manhattan is almost unrecognizable from its bustling days a century ago. However, one site that has (somewhat) remained is the Eldridge Street Synagogue, which was built in 1887 as the first great house of worship by Eastern European Jews in the United States. Designed by German Catholic architects Peter and Francis Herter, the synagogue embodied the promise of religious freedom and the formation of Jewish-American identity.

For decades, the synagogue thrived. But many Jewish families began to move away from the Lower East Side in the 1920s, with new immigration restrictions preventing many families already here from reconnecting with loved ones. Post-World War II, the congregation closed its main sanctuary and met instead in the basement, leaving the main floor essentially abandoned. After decades, the dust inside was so thick you could write in it, and cobwebs hung between the pillars. There was extensive water damage to the dome, with water pouring in from the openings. Pigeons had even taken roost in the balcony. In 1987, the Eldridge Street Project was formed to restore the synagogue to its former grandeur. Twenty years and $20 million later, the building reopened as the Museum at Eldridge Steet.

Artist Kiki Smith and architect Deborah Gans designed a rose window made of 1,200 individually shaped pieces of colored glass, etched with more than 650 stars. The ark and bimah, the sacred areas of the synagogue, are made of fine walnut. Every part of the restoration was painted by hand — although many components of the synagogue were painted to look real but are not, such as trompe l’oeils on either side of the ark that show a traditional curtain over the ark doors. There’s also a hidden heart on the ceiling instead of a spade, which was “perhaps put there by a romantic artisan” according to the Museum. Additionally, there remains a historic wall deliberately left bare along the left balcony of the upstairs sanctuary.

Kehila Kedosha Janina is a historic synagogue on 280 Broome Street between Allen and Eldridge streets. Built between 1925 and 1927, it is the only Romaniote rite synagogue in the Western Hemisphere. Romaniote Jews are one of the oldest Jewish communities in existence and spoke a distinct language called Judaeo-Greek at locations such as Thessaloniki, Corinth, Thebes and Preveza.

The congregation was founded in 1906 by Greek Jewish immigrants from Ioannina. Between the building’s erection and World War II, there were three rabbis in the synagogue, and on the High Holidays, there was often only standing room for synagogue services. However, the success of the Romaniote synagogue was quite short-lived, since many congregants moved to other boroughs and more northern parts of Manhattan. Today, the synagogue has about 5,000 members but struggles to assemble a minyan, or 10 people, for Shabbat services.

Kehila Kedosha Janina is rather unusual for a Romaniote synagogue since it runs from north to south with the ark on the north side as opposed to east to west. The bimah is in the center of the main sanctuary and not on the west wall. Men and women do sit separately, a common feature of Orthodox synagogues. The second-floor women’s gallery contains a museum with artifacts, exhibits and Judaica on Jewish life in Greece. The building’s brick exterior contains a number of Stars of David, the Ten Commandments and a centerpiece above the main doorway.

58-60 Rivington Street used to house a Romanian synagogue operating under the name First Warschauer Congregation. In 1886, a group of Romanian Jews established the congregation Kehal Adath Yeshurin of Yassay at 131 Hester Street, and in 1903, the congregation planned an upgrade for 58-60 Rivington. Emery Roth — the architect behind dozens of New York buildings like The San Remo, The Beresford and the Ritz Tower — was commissioned to create a new synagogue in the Moorish Revival style, relating back to the pre-Inquisition period in Spain. The interior plan included two separate women balconies, and the sanctuary could accommodate up to 500 worshippers. In 1904, the congregation’s sacred Torah scrolls were marched in a four-hour parade to the new location, with as many as 300 policemen escorting the thousands of marchers.

Among the synagogue’s most prominent congregants were George and Ira Gershwin, who both grew up on Eldridge Street, Republican New York Senator Jacob Javits, co-founded of MGM and film producer Samuel Goldwyn, and comedian George Burns. The American Jewish Federation sponsored an event there “to combat fascism and communism” in 1938. Following the Holocaust, the congregation grew in size as Eastern European immigrants settled on the Lower East Side. Yet the synagogue also faced financial struggles just a few years later, as many families left the area for better housing elsewhere in the city. By 1973, the building was vacant, and six years later, the SoHo-based sculptor Hale Gurland transformed the space into artist studios and living quarters. The building’s facade, which features rows of alternating beige and reddish bricks as well as a central spiral window, still remains intact.

Straus Square on East Broadway and Rutgers Street was the go-to spot to get the news a century ago. Straus Square is named for Nathan Straus (1848-1931), the international representative for L. Straus & Sons, the family’s crockery and glass firm. His father, Lazarus, emigrated to America in 1852, and the rest of the family followed him to Georgia in 1854. Although Nathan took Sunday School classes with a Baptist minister, he also took Hebrew lessons in Alabama before moving to New York. Nathan traveled across America to open new markets and throughout Europe to acquire new products for the firm. The Strauses were sole owners of Macy’s in Manhattan and were partners in the Abraham & Straus department store in Brooklyn. To promote welfare in the community, Nathan provided a dining hall with full meals for just five cents, as well as offering personal gifts of money, clothing and medical treatment. Tragedy struck his family when his wife and brother died aboard the Titanic in 1912, after which he retired from business and devoted himself to charity and public service.

At Straus Square, many immigrant Jewish families would come to get their news. Because many families could not afford to buy a newspaper, people would crowd around the square to get their daily news fix, especially during World War I. The site was also a popular place for protests, where many progressive Jews would listen to speeches by activists such as Lillian Wald and Emma Goldman about workers’ rights. Nathan would also sell milk in the square, and he supplied a milk bar on the roof garden of the Educational Alliance, a settlement house and a community center which stands to the east of Straus Square. In 1953 the Manhattan Borough President and members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars gathered at the site to dedicate a monument to the men and women of the Lower East Side who served in World War I, World War II, and the Korean War.

The Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation building on 87 Eldridge Street is located at the site of a 100-year-old former synagogue. 87 Eldridge Street was once the home of the congregation Bnai Tifereth Yerushalaim, which purchased the property in 1888. Originally built as a tenement apartment in 1874, the building served the congregation until the 1960s when it was then acquired by the Syrian Orthodox institution Achim Aram Zobah. It was later sold to an African Methodist Episcopal Church, which occupied the building until the 1970s. Abstract-expressionist artist Milton Resnik bought the building and converted it into his studio and residency. His wife and fellow artist Pat Passlof also worked in a synagogue at 80 Forsyth Street. In 2015, the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation was established for the preservation, exhibition, and publication of works by Resnick and Passlof.

Although the building has changed ownership a few times, much of its Lower East Side Jewish history is preserved in the architecture. In the center of the facade is a Star of David in between two patterned arches. Also between the two windows is a plaque in Hebrew.

Stanton Street Synagogue is a historic synagogue located at 180 Stanton Street. It was constructed in 1913 by a landsmanshaft from Brzeżany in southeast Galicia, Ukraine. The tenement-style synagogue is one of the last in the city, and it remains an Orthodox house of worship today. Jewish immigrants from Galicia organized Congregation Bnai Jacob Anshei Brzezan as a mutual aid society in 1894. The synagogue incorporated two existing structures dating to the 1840s: a three-story wood-frame front house and a brick back house.

In 1952, following a drop in membership, the synagogue merged with Bnai Joseph Dugel Macheneh Ephraim, which was founded by Polish-Jewish immigrants from Rymanów and Błażowa. Rabbi Joseph Singer worked as an advocate for the poor and elderly of the neighborhood, and he served in the role from 1964 until 2002. The run-down synagogue was sold to the National Theatre Workshop of the Handicapped in 2000, and Singer left the neighborhood. Less than 100 people remained as members around the turn of the century, but the synagogue experienced a revival over the past two decades. The synagogue was built in the Neoclassical style and prominently features four Stars of David, including in the oculus above the main entrance. In the center of the synagogue is a wooden bimah and a wooden Ark, and the sanctuary has a tin ceiling. Wall paintings around the main sanctuary depict the Zodiac signs for the twelve Hebrew months.

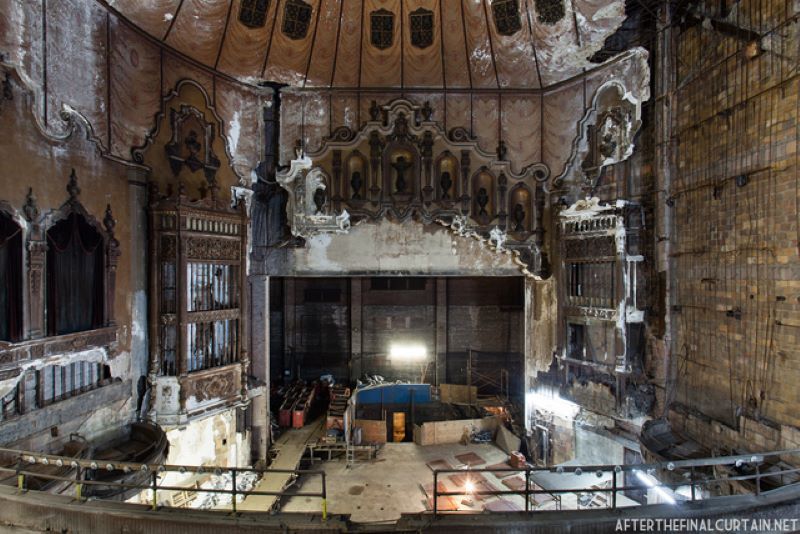

The Loew’s Canal Theatre at 31 Canal Street was built in 1927 and has been closed since the 1950s. When it opened, it was the second-largest theater in New York City with 2,314 seats. Loew’s eventually sold it to Greater M&S Circuit, but it didn’t survive long as it went bankrupt in 1929, and was bought back by Loew’s the same year. The Canal was designed by Thomas Lamb, who designed many of the forgotten theaters of Upper Broadway and showed mostly “B” movies and serials. Loew’s Canal Theatre was a popular theater for the local Jewish community, selling tickets for affordable prices and showcasing films relevant to the community. Loew’s also showcased some Yiddish productions and hosted events for the Jewish community, as did the nearby Grand Theatre, “the first theatre in America built for the express purpose of housing Yiddish productions.”

On September 10, 1932, both the Canal and the 46th St theatres were rocked by explosions set off by bombs. The attack was believed to be connected to the Motion Pictures Operators’ Union Local 306 who were on strike at the time. The theater recovered with minimal damage, but after closing in the 1950s, the lobby was converted into a retail space with the auditorium as warehouse space. The Canal Theatre has been abandoned since the early 2000s. The interior has been left to decay, but its terra cotta facade remains protected. In February 2015, artists 2ESASE of art collective UR New York and artists SKI created Art Deco-inspired posters that featured figures from the 1920s and hung them throughout the building.

80 Forsyth Street is one of the last remnants of the street’s many synagogues from the late 1800s. In 1874, the property was owned by the Schwartz family, which was converted into a furniture store that sold rather upscale items. However, the store was short-lived, and on March 28, 1881, the Congregation Kol Israel Anshe Poland purchased 80 Forsyth Street for $12,000. After a series of renovations, the building featured two-story Gothic-arched windows, filled with stained glass originally. And wrought iron fire escapes incorporated Stars of David into the design. The building included a mikveh, or a ritual bath, on the ground floor. Even though the building functioned as a synagogue, it was still taxed, leading to a lawsuit.

The synagogue was sold in 1892, and in its place came the congregation Beth Hamidrash Sha’arei Torah. In addition to lavish weddings, the synagogue also hosted some unfortunate funerals, such as that of Freda Marks, who succumbed to a disastrous fire in a tenement building just down the street. The congregation sold the building in 1930, and the Manhattan Store Fixtures Company moved in soon after. The building is now painted an industrial green and today honors the works of Pat Passlof. Uncover more Jewish history sites on the Lower East Side by joining our upcoming Secrets of the Lower East Side tour and tasting!

Next, check out more Jewish history on the Lower East side by exploring 10 Repurposed Synagogues and the Top 10 Secrets of Eldridge Street Synagogue and Museum in NYC!

Subscribe to our newsletter