Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

On October 1, 1955, The Honeymooners premiered on CBS Television. The classic 39 episodes of that first and only season would achieve cult status and rerun for decades. The legendary sitcom, set in Brooklyn, starred the borough’s favorite son, Jackie Gleason, as bus driver Ralph Kramden and Audrey Meadows as his wife Alice. Neighbors Ed Norton (Art Carney) and Trixie Norton (Joyce Randolph) completed the cast.

Ralph’s get-rich-schemes and expansive waistline provided much of the comedy, but the laughs belied Gleason’s turbulent childhood. Gleason was born on February 26, 1916, to Mae and Herbert Gleason when the family lived at 364 Chauncey Street in Brooklyn. The Gleasons later moved to 358 Chauncey Street, but Gleason most fondly remembered his years spent in apartment 3-A of 328 Chauncey Street. The Gleasons’ dingy flat would serve as the model — and the address — of the Kramdens’ fictional apartment. While 328 Chauncey Street is actually in Stuyvesant Heights, the show took place in Bensonhurst.

Gleason was named “The Great One” by Orson Welles, “although I don’t know if he meant my talent or my drinking capacity,” Gleason said. Gleason, who also starred in the films The Hustler and Smokey and the Bandit, honed his comedic talent as a teenager in Brooklyn’s lodge halls and vaudeville houses. Here, as his birthday approaches, we take a look at 10 of his Brooklyn haunts. And away we go!

“Gleason patterned the Kramden apartment after the one he lived in with his mother as a boy,” Dina-Marie Kulzer writes in Classic Hollywood Bios. “The address is even the same, 328 Chauncey Street. ‘The place was dull. The bulbs weren’t very bright. The surroundings were very bare,’ remembered Gleason about his childhood home.”

Jackie’s father, Herbert Gleason, a Death Claims clerk at the Mutual Life Insurance Company, was an alcoholic and gambler. “My pop was a $37-a-week clerk named Herbert Gleason and Mom was Mae Kelly Gleason, an Irish girl,” Gleason recalled in The American Weekly. “I was their second son, born in 1916, and poverty was something everybody in our neighborhood took for granted and didn’t fret about. Pop just walked away from his desk one day when I was nine — and he never came back.”

The Kramdens often battled but always made up in their kitchen. The furnishings never changed: an icebox, stove, sink, dresser, a table in the center, and no curtains on the window. Jackie Gleason: An Intimate Portrait of the Great One explains that Gleason told his set designers, “Get a Brooklyn tenement and make it scruffy.” When a picture was placed on the wall next to the bedroom door, Gleason said, “We didn’t have a picture in the flat. Take it down.”

Frieda Broodno Storm grew up in the tenement and described Gleason’s Chauncey Street flat in The Honeymooners Lost Episodes. “The one big difference between the Kramden apartment and Jackie’s was that in Jackie’s, the bathroom was in the hall, and the tub was in the kitchen adjacent to the sink.”

Gleason was eight when he entered P.S. 73 in Bedford-Stuyvesant. “Jackie was late in going to school, but it didn’t seem to matter, because he could already read, thanks to his mother, and he had an unusually retentive memory,” notes author William John Weatherby in Jackie Gleason: An Intimate Portrait of the Great One. “He soon became a nuisance to teachers, because he read ahead of the class and asked awkward questions and argued with the faculty.”

Among the pranks Gleason played at P.S. 73 was spreading Limburger cheese on the radiators, ensuring early dismissal as janitors searched for it. Gleason credited graduation day at the school as his start in show business.

”I did a recitation of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ in Yiddish, and in the middle of it, I knocked over the cardboard prop microphone,” Gleason recalled in the Chicago Tribune. “The principal leaned over to pick it up, and I said, ‘That’s the first thing you ever did for us kids.’ On the way home, my mother told me, ‘You were good, but you were too fresh.’”

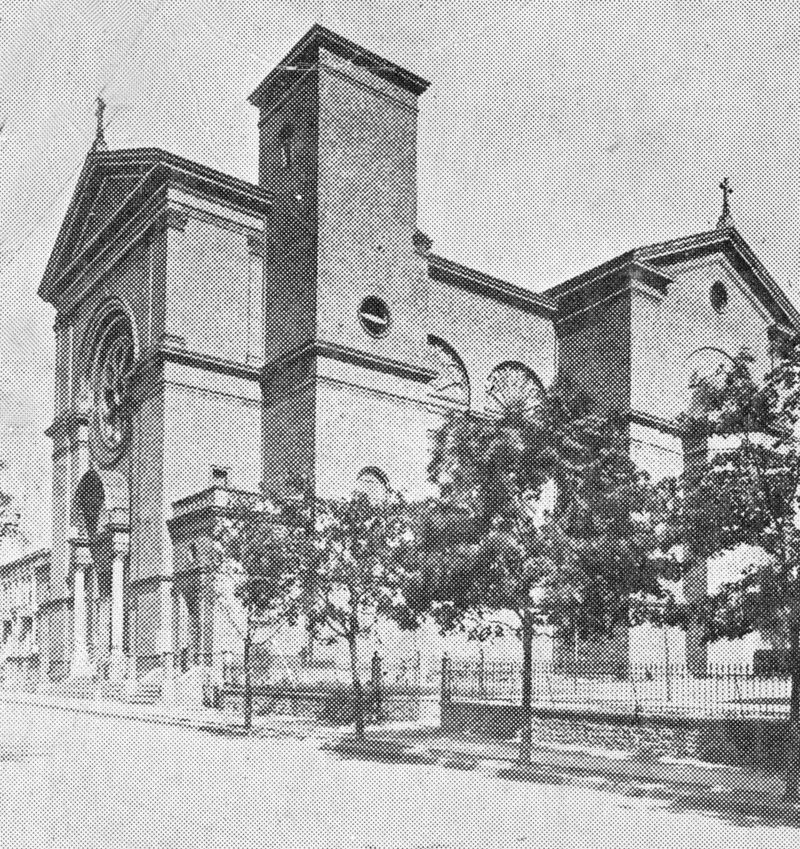

Asked by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle to recall some childhood memories, Gleason wrote, “Attending Public School 73 and standing in line those cold winter mornings until the monitor would allow us to march into the building. Going to confession at Our Lady of Lourdes and getting the worst scolding of my life from Father Berlin (God rest his soul) when he asked me how many times I had disobeyed my mother. And I answered, ‘Four hundred and thirty-nine times.’” In How Sweet It Is, Gleason recalled the holidays after his father’s departure on December 15, 1925. “On Christmas Eve, Mom and I went to midnight mass at Our Lady of Lourdes Church. I prayed that Pop was still alive — and that he would come back to us. I was scared to death.”

On Nov. 17, 1975, the New York Times reported, “A Roman Catholic church that had been a Brooklyn landmark since 1897 was destroyed last night by a spectacular three alarm fire that burned out of control for more than three hours. Flames inside the church set stained glass windows aglow before burning through the roof and engulfing the entire brick building extending through the block to De Sales Place.” It was later determined that an arsonist set fire to the church, which had to be demolished.

A few blocks from Gleason’s apartment is P.S. 137, “which accommodated students up to the sixth year of primary school,” notes The Golden Ham, “and which had a schoolyard designed for Gleason and his friends. “They played stickball and basketball, and when it rained, they forced the door to the school after hours and played downstairs in the gymnasium.”

Today the school is named P.S. 137 Rachael Jean Mitchell School. It serves pre-kindergarten through 8th-grade students.

“I only graduated from grammar school,” Gleason explained in People magazine. “I went to high school, but I got my cousin’s boyfriend to come to school and explain how poverty-stricken my mother was. He said it was absolutely necessary that I get out of school and go to work. By then I was hustling pool. I’d started when I was 10.”

“The last thing Mae Gleason wanted to do was pull Jackie out of high school,” The Golden Ham points out. “He spent another few weeks at a trade high school, but in all, Jackie had only about a month of high school education.” Today Bushwick High is known as the Brooklyn School for Social Justice. The school encourages students “to be active in the social, cultural, and political lives of their communities and their world.”

In happier times, Herb Gleason took his young son to the Halsey Theater on Saturday afternoons to watch silent comedies and vaudeville acts. “I was five years old and my father took me to the old Halsey Theater,” Gleason told People magazine, “I thought it was sensational. When the lights went on for intermission I got up, turned around, and faced the audience. That was even greater than watching the guy on stage.”

At 15, Gleason won an amateur contest at the Halsey with an act he put together with one of his buddies. Gleason later replaced a friend, Sammy Birch, as the Halsey’s master of ceremonies. Gleason was once suspected of releasing a snake in the orchestra pit.

Gleason’s mother Mae disapproved of her son’s first job as an entertainer. “She hated me to tell jokes or have anything else to do with show business. When I became the emcee at the Halsey years later, she said, ‘You look silly up there.’ I knew she liked it, though she’d never admit it.” The theater closed around 1945 and was demolished. Saratoga Square housing for seniors now occupies the site.

The Bushwick Theater opened on September 11, 1911. The venue “was once Brooklyn’s largest and most magnificent vaudeville theater with seating for 2,500 patrons,” notes Brooklyn’s Bushwick. Ethel Barrymore and Lily Langtree were among the stars to perform there. Brooklyn Relics reveals that a unique feature of the Bushwick was its animal room, “an area underneath the stage built to house the many animal acts that were once included in vaudeville shows. Its design was sufficient in size to accommodate dogs, monkeys, horses, elephants and other beasts.”

Comedian Phil Foster recalled in How Sweet It Is that Gleason made some of his earliest appearances at the Bushwick. “Jackie must have been around sixteen or so. I know he had quit school, as that was the legal age. We all entered amateur contests at the Bushwick Theater. He bombed like the rest of us but he kept trying.”

A movie screen was added in 1930 and the theater became part of the RKO-Keiths chain until it closed in 1969. The Pilgrim Baptist Cathedral reopened the building as a church in 1970. Today the building houses the Brooklyn University High School for Law.

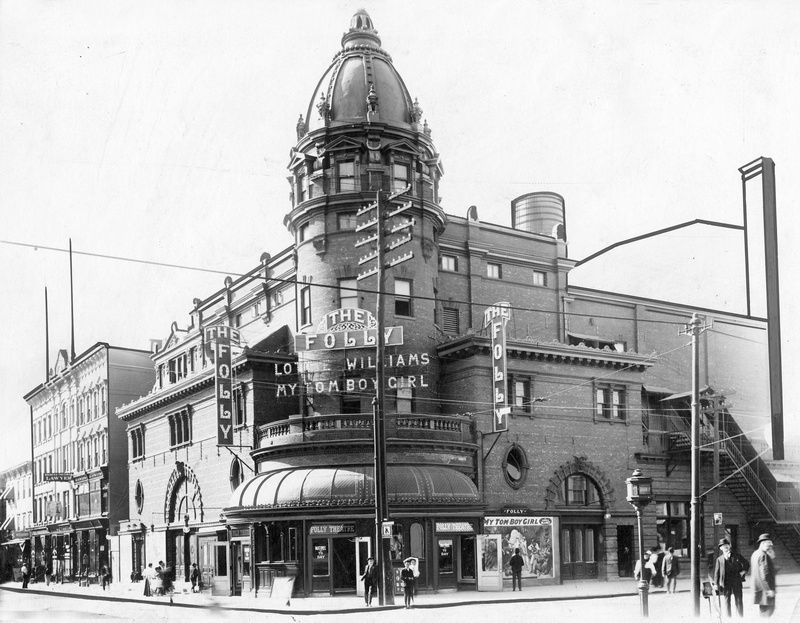

Gleason worked as a part-time master of ceremonies at the Folly Theater every Monday and Friday night. “After graduation,” Gleason recalled in Family Weekly, “I went to work for $2-a-night amateur nights at the Folly Theater in Brooklyn.” The Williamsburg theater opened as a vaudeville house in October 1901. Its opulent design included a large central domed tower, classical statues, paintings and gilded mosaics.

Mae Gleason died in 1935, two months after her son’s nineteenth birthday. ‘‘My mother became my whole life. My instructor, my benefactor, my security,” Gleason told the Knight News Wire in 1977. “The night my mother was buried, I had to do the show at the Folly Theater. I had $1.36 when I walked from the stoop where I lived. I spent ten cents coming and going and had two waffles, with apple butter and cream. I had a nickel left when I got home. That is a standing start.” The Folly closed in 1939 and went unused until it was demolished in 1949.

Like the Folly and Halsey Theaters, the Majestic Theater in Downtown Brooklyn provided Gleason with steady work in 1934 during the Great Depression. “He often worked two or three theaters at a time,” notes Historic Greenpoint, “skipping from Brooklyn to Jersey and back again in a single night.”

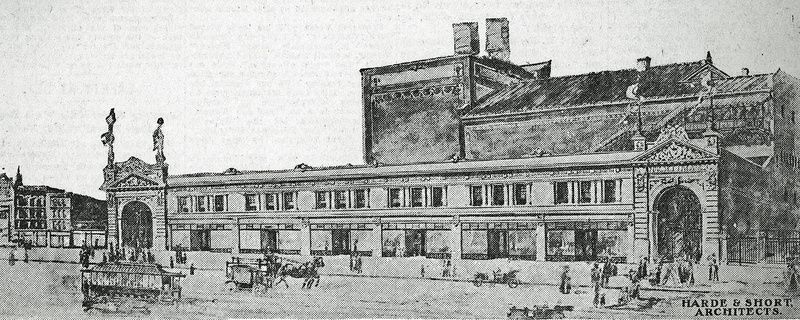

The Majestic, with more than 1,700 seats, opened on August 29, 1904, one of many legitimate theaters in Downtown Brooklyn. In the 1900s, the Majestic presented vaudeville, light opera, dramas, musicals, opera, and film. It became a trial theater for Broadway-bound plays.

In 1942, the Majestic became a first-run movie house, playing triple features in the mid-1950s. The Majestic remained closed for nearly two decades after it shut its doors in 1968. By 1986, the Majestic was in disrepair. It had suffered extensive water damage, the plaster on the walls were peeling, and the stage floor was collapsing. Enter the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) president and executive producer Harvey Lichtenstein.

Lichtenstein was searching for a theater to stage Peter Brook’s production of The Mahabharata. Brook discovered the Majestic and Lichenstein raised funds to renovate the theater. Completed in 1987, its design pays homage to the original Majestic by preserving many of its original features.

“They loved the ruinous look of it,” said BAM archivist Sharon Lehner in Playbill, “and that you can’t sit in the theater without being reminded of its history. In the beginning, I think they did intend a ‘phase two’ renovation. But the more time they spent in the space, the more they realized how much they liked it just the way it is.” In 1999, the Majestic was renamed the BAM Harvey Theater to honor Lichenstein’s contributions.

Early in his career, Gleason performed with his friend Charlie Cretter. “He put together an act he called ‘The Sardonic Spectator’ from old gag books and arranged a booking for him and Charlie at the Brooklyn Masonic Lodge,” notes Jackie Gleason: An Intimate Portrait of the Great One. “Charlie came on stage to announce his partner hadn’t shown up, and then Jackie, sitting in the crowd, yelled insults at him in Yiddish dialect. Then he rushed up to the stage, falling over three times in his haste like his favorite comedians in silent slapstick movies.”

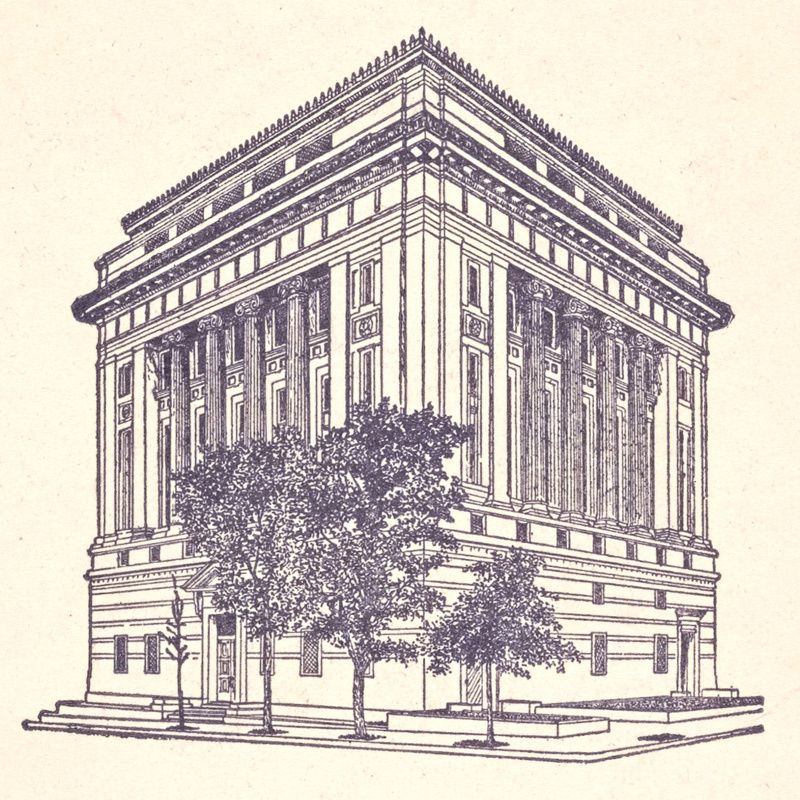

The Brooklyn Masonic Temple was built in Fort Greene in 1907. Thirty-five lodges shared its meeting rooms and an auditorium that seated 1,000. Political meetings and lectures were held there to provide income for the temple. Rooms continue to be available for weddings, receptions, and other events.

Like 328 Chauncey Street, the writers of The Honeymooners often included real Brooklyn addresses and locations in scripts although all scenes were filmed at the Adelphi Theater in Manhattan. In the episode “Pal O’ Mine,” Ralph is told that Norton was injured in a sewer explosion on Himrod Street and had been taken to Bushwick Hospital, a real infirmary when the episode aired November 19, 1955. Ralph rushes to the hospital and offers to give Norton a blood transfusion, only to find his pal has already been released.

Carney ad-libbed a line at the hospital that is beloved by Honeymooners fans. “For some reason or other it came to me,” Carney explained in The Official Honeymooners Treasury. “What would Norton say, when he was saying goodbye to a doctor, to give the doctor the impression he was in the know? What would he say? Rx! That was a goodbye.”

Bushwick Hospital was built in 1912. Today the building houses the Ella McQueen Residential Center, a New York State juvenile detention center.

Next, check out more NYC history from the author’s books on Manhattan’s Downtown and Uptown ghost signs; the secrets of rock concert venue Fillmore East; and rock n’ roll sites you can visit today.

Subscribe to our newsletter