Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

The Bronx still boasts its fair share of grand homes, but many mansions of New York City’s northernmost borough have been lost to time. The Bronx once offered a rural retreat for wealthy New Yorkers desiring to escape the hustle and bustle of the city. They built opulent summer homes in places like Pelham Bay and Hunts Point where they could enjoy views of the Long Island Sound and the East River. As the city expanded northward, these estates were eventually enveloped by the growing urban footprint of New York City, taken over by industry, higher-density housing, and parkland. Revisit 7 lost mansions of the Bronx here!

In 1792, the Lorillard brothers purchased a grist mill and fifty acres of land along the Bronx River. The Lorillard’s came from a wealthy French Huguenot family who made their fortune in the tobacco industry with snuff. In the Bronx, their business continued to flourish as they developed innovative new methods for producing powdered tobacco. They built multiple mills on the property, the third of which still stands today.

In addition to the snuff-producing facilities, the estate contained the lovely Lorillard Mansion, built in 1856 for Pierre Lorillard III and his wife, Katherine Ann Griswold. The 68-room stone mansion was three stories tall. When Pierre died, the home was passed to his son Pierre Lorillard IV. The fourth Pierre moved the family tobacco factory again, this time to Jersey City. In 1884, Pierre IV sold the grounds of the Lorillard estate to the City of New York, which in turn transferred part of the land to the New York Botanical Garden in 1915. The mansion was converted into a museum and was used by the Bronx Society of Arts & Sciences. It caught fire in 1923 and the remnants were demolished. The legacy of the estate lives on as the grounds that are now part of the Botanical Garden.

Nathaniel Platt Bailey’s name can still be found in the Bronx, but his mansion is lost. Bailey, a wealthy 19th-century businessman and landowner, lends his name to Bailey Avenue and Bailey Playground. He settled in New York City in 1824 and was so successful in his early career that he was able to retire at the age of 35. His vast estate, according to the New York City Parks Department, “covered a part of what is now called West Fordham, extending from Fordham Road to Kingsbridge Road and from Bailey Avenue to University Avenue.” Bailey’s wife with whom he shared the mansion was Eliza Meier Lorillard, a descendant of the Lorillards who owned the mansion at what is now the New York Botanical Garden.

Bailey’s large mansion overlooked the Harlem River and is reported to have had views that stretched all the way to the New Jersey Palisades. When he died in 1891, the land was divided up and partly sold to the Roman Catholic Orphan Asylum. Today the former estate site is largely occupied by the James J. Peters Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center. This lost Bailey mansion is not to be confused with the one that still exists today in Sugar Hill, Manhattan. That mansion belonged to James Bailey of Barnum & Bailey Circus fame.

The Claremont Mansion or the Zborowski Mansion once stood on an estate where Claremont Park is today. The massive home was built in 1859 for Elliott and Anna Zborowski de Montsaulain. The 38 acres of land on which the mansion stood were in the northern part of what used to be the Morris family estate. One of the founding families of the Bronx, the Morrises established their estate in 1679. Much of the Morris land was auctioned off in 1848 as the city expanded.

Claremont Mansion was known for its white marble sculptural decor and terraced lawns that cascaded down to the Mill Brook, which is now Webster Avenue. After the 1884 New Parks Act went into effect, the city purchased land for Claremont, Crotona, Van Cortlandt, Bronx, St. Mary’s, and Pelham Bay Parks in 1888. The estate grounds became parkland and the mansion was converted into the administrative headquarters of the Bronx Parks Department. A dangerous incident occurred at the mansion in the early 1900s. One rainy day, while parkgoers sought refuge on the mansion’s veranda, the porch collapsed into the cellar. Over a hundred people tumbled down into the cellar and some had serious injuries. The Parks Department headquarters were relocated in 1938 and the mansion was demolished. Today, at the site of the lost mansion you’ll find a gazebo.

In 1804, John Hunter purchased an island in the Long Island Sound, just off the northeast coast of the Bronx. The island had gone by many names up to that point. First occupied by the Siwanoy Indians, it was acquired by Thomas Pell in 1654 and became Pell’s Island. It was also known as Pelican’s Island and Appleby’s Island when Hunter purchased it. On the island, Hunter built a large stone and brick mansion for himself and his wife, Elizabeth Desbrosses in 1811.

The mansion cost $40,000 to build, but the treasures kept inside were worth much more. Hunter filled his mansion with old master paintings by the likes of Rembrandt, Rubens, van Dyck, and da Vinci. His collection of over 400 pieces was estimated to be worth $130,000 at the time. Hunter Mansion was one of the dozens built in the Pelham Bay area in the 19th century as wealthy New Yorkers sought more space and proximity to the water for their summer getaways. In 1866, Hunter’s heirs sold the summer home on the island to former Mayor of New York Ambrose C. Kingsland. Kingsland entertained dignitaries including President Martin Van Buren. After Kingsland, a few other owners had control of the property until it was eventually sold to the City of New York in 1889.

The mansion soon became the “Holiday House” of the Little Mothers Aid Association, a children’s welfare house that helped young girls. By the 1930s, the once grand mansion had fallen into disrepair. In 1937, Robert Moses decided to connect Hunter Island with Rodman’s Neck and Twin Islands to be part of Pelham Bay Park. Moses’ $8 million project resulted in the creation of Orchard Beach, a 6,800-car parking lot, a pavilion, a bathhouse complex, and a promenade. It also entailed the demolition of the Hunter Mansion.

Today, Hunter Island is the Hunter Island Marine Zoology and Geology Sanctuary. That part of the park features tidal wetlands and woodlands, old oak trees, and nature trails.

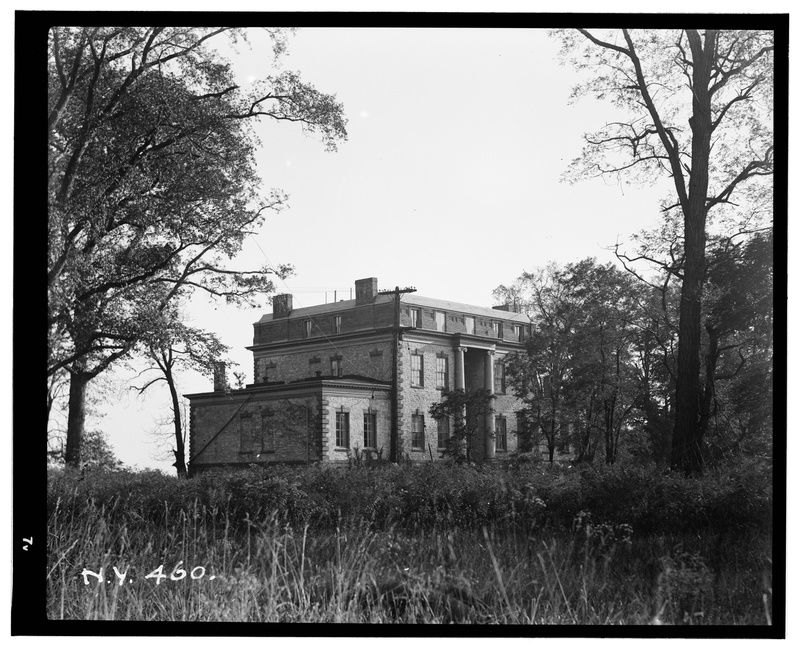

Hawkswood, the mansion of southern businessman Levin R. Marshall, came to a similar fate as Hunter Mansion. It was originally built on Rodman’s Neck, now Pelham Neck, by a wealthy New York City lawyer named Elisha W. King in the 1820s. King lived there until his death in 1836 and the mansion was later sold at auction along with 80 acres of land. It was purchased by Marshall and became known as Marshall Mansion. The Grecian-style stone home faced the Long Island Sound and City Island. The grounds were landscaped by Belgian gardener Andrew Parmentier and were one of the few major projects that he designed in the United States.

The mansion and surrounding grounds were acquired by the state in 1888 along with a slew of other areas to be turned into parkland. The City rented out the mansion for use as a restaurant in 1913 and it became known as the Colonial Inn. By 1937, when Hunter Mansion came down, Hawkswood had also aged. The mansion was torn down the same year.

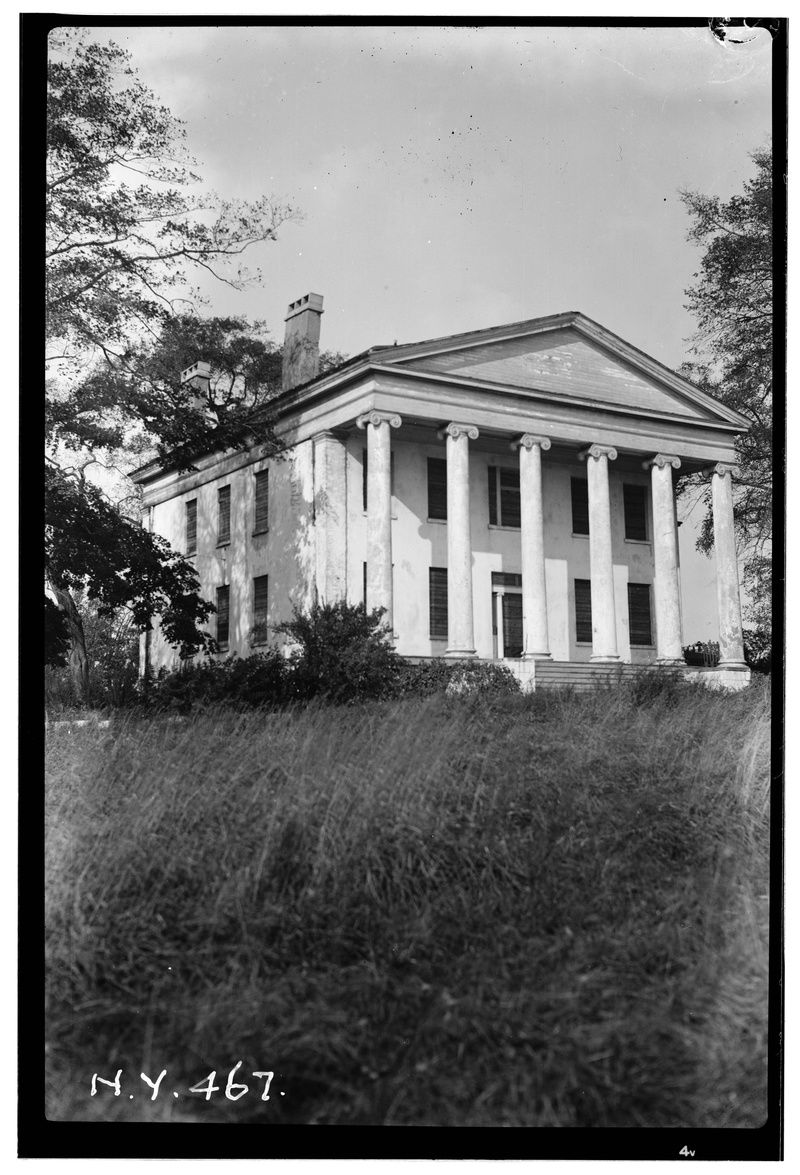

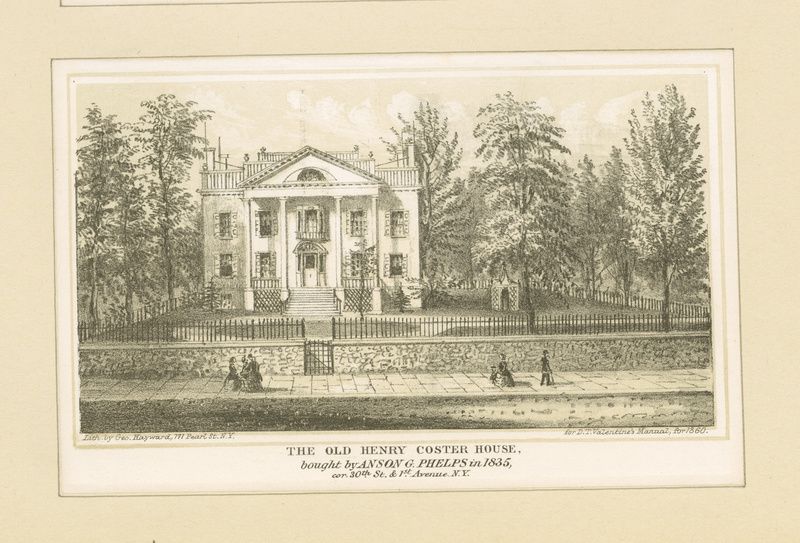

Daniel Joachim Coster and his wife Julia DeLancey didn’t build their mansion until 1838, but their estate existed from 1771. During the Revolution, the site of their future home was in dangerous territory, then considered part of Westchester County, now the neighborhood of Throgs Neck in the Bronx. It stood on land near what would become Edison Avenue and Greene Place.

Daniel was the nephew of one of New York City’s first millionaires, Henry A. Coster, a merchant from Holland. Daniel based the design of his own mansion on that of his uncle’s mansion in Kips Bay. Naming it “St. Adresse,” the mansion was a bit less ornamented than his uncle’s, but shared the classic Greek Revival style with a plain pediment held up by four Doric columns. Surrounding the mansion was an orchard and flower garden. St. Adresse stayed in the family for nearly a century until it was inherited by Daniel’s grandchildren, Oliver and Martha. The descendants broke up the estate into 250 different lots and sold the mansion to The Parish of St. Benedict’s in 1929. The Parish demolished the house to make way for the St. Benedict School which now stands in place of the lost mansion,

One of the most elaborate lost mansions of the Bronx once stood on the Hunts Point peninsula, then known as Oak Point. The formerly rural area once dotted with grand estates on the rural land of Westchester County is now part of the Bronx and characterized by food distribution sites like the city’s produce market and Fulton Fish Market. Before industry took over, places like the mansion of Benjamin Morris Whitlock were the norm.

Whitlock’s nearly one-hundred-room mansion stood on fifty acres of land. The extravagance of the home earned it the title of Whitlock’s Folly. To approach the mansion, guests had to pass through a large iron gate and travel over a drawbridge. Inside, the mansion boasted “decorations imported from France, gold knobs..and…woodwork carved of cherry and mahogany.” There were wine cellars and wells that supplied running water as well as ammunition vaults underground. After Whitlock, the home was owned by Cuban sugar importer Inocencio Casanova. Then dubbed Casanova’s Mansion, it served as a site for the importer to host advocates for Cuba’s independence. By 1902, the mansion had been abandoned for over a decade and was acquired by a developer. At the site today you’ll find the Oak Point CSX freight rail yard.

Next, check out This 19th Century Sunnyslope Mansion Still Stands as a Church

Subscribe to our newsletter