Our quest to revive the lost mansions of New York continues as we travel to Staten Island. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Staten Island was a popular destination for wealthy New Yorkers looking to create a country retreat, while remaining in close proximity to the hustle and bustle of the city. As real estate development picked up in the 1900s, these grand estates were split into smaller lots, and their massive houses were abandoned as owners sought other locales. Here, we explore the lost mansions of Staten Island that once belonged to Vanderbilts, beer barons, actors, and more!

1. Hormann Castle, Grymes Hill

This fairytale castle that once stood upon Grymes Hill was built in 1910 by William Hormann, heir to the Rubsam and Horrmann Brewing Co. fortune. The Stapleton brewing company was founded by William’s father, August, in 1871. William’s castle was inspired by castles found on the Rhine in Germany, his family’s homeland. The grand mansion with an imposing tower with an open-air onion-topped turret sat on 11 acres of land high above the town of Stapleton with a view out to New York Harbor.

The Hormanns sold their storybook home in 1945 to the Roman Catholic Presentation Sisters. Nuns who taught at St. Clare’s School in Great Kills lived there until 1965. Just two years later, the abandoned mansion near present day Eddy Street was demolished. Today, the gated community of Howard Circle stands in its place.

2. Bay Villa, New Brighton

The elaborate Second Empire mansion at Bay Villa was built around 1862 for John M. Pendleton. It was one of three large estates built around the same time atop the hill that rises between St. Mark’s Place and Hamilton Avenue. The mansion stood on just over five acres of land and was accompanied by a carriage house, gardener’s lodge, and gatehouse. While scouting for a country retreat, wealthy merchant banker Anson Phelps Stokes spotted the property. His family initially rented the mansion. They quickly fell in love with the property and he purchased the home in 1868. The family would return every spring and fall season until 1886.

By the 1880s, Staten Island had become too crowded for the Stokes. Their estate was near the ferry dock where crowds of people would disembark on their way to Staten Island’s amusement parks at St. George and Erastina. Like many of their wealthy friends, the Stokes left Staten Island for a quieter retreat on Long Island and in the Berkshires. The Bay Villa estate was split into individual lots and sold for development. The cul-de-sac of present-day Phelps Place was part of Stokes’ development, and houses built there in the 1890s are now part of the St. George Historic District. The main house was sold in 1892. By the late 1920s, it had fallen into disrepair and was demolished in 1930.

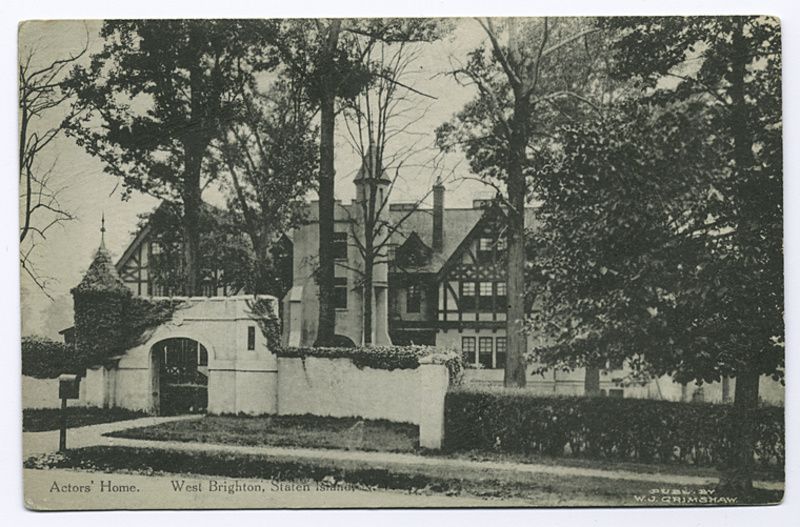

3. Actor’s Home, New Brighton

This Elizabethean-style mansion on Clove Road near Clove Lakes Park and Martlings Pond was originally built for Civil War hero Col. Richard Penn Smith, but in the early 20th century it was inhabited by dozens of retired vaudeville stars. At the behest of 19th-century actor Joseph Jefferson who had been a guest of the Colonel’s, the Actor’s Fund of America purchased the Colonel’s mansion and in 1902 opened The West Brighton Actor’s Home. The home was for retired vaudeville performers once their careers on stage had ended. The mansion stood on 14 acres of Smith’s 20-acre estate.

Inside, the house was furnished by R.H. Macy. One the ground floor there were salons, a dining hall, a billiard room, and a parlor. On the upper floors, there were nearly 50 bedrooms and dozens of bathrooms. In 1928, the Actor’s Home was relocated to a larger residence in Englewood, New Jersey donated by millionaire businesswoman Hetty Green. The New Brighton House stood for a decade longer but was demolished in 1938. Today, the site of the lost Staten Island mansion is occupied by St. Peter’s Cemetery and the parking lot for the Staten Island Zoo.

4. The Commodore’s Mansion, Stapleton

The very first of the many grand mansions built for Cornelius Vanderbilt I, aka The Commodore, was constructed in 1839 between Stapleton and Tompkinsville. Vanderbilt built the mansion for himself and his wife on the northeast corner of his father’s farm. Boasting views of the bay at Stapleton, the home cost $27,000 at the time.

The style of the mansion was “modified Gothic” with six fluted columns and a Grecian portico. The materials it was made of included yellow Virginia pine, imported Egyptian marble, French plate, and South American mahogany. Six short years after the house was complete, Vanderbilt and his wife moved to Manhattan to an even bigger abode. The Staten Island home was purchased by financier George Law and then later George H. Daley. A fire struck in 1882 but the mansion persisted until the early 1900s when it was demolished. Today, a row of low-rise buildings stands in its place.

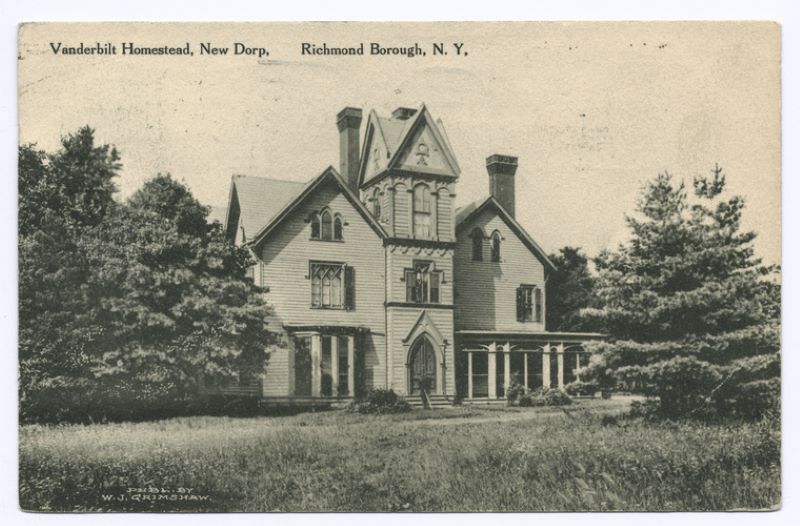

5. Vanderbilt Homestead, New Dorp

Another New York Vanderbilt estate that once stood on Staten Island belonged to Cornelius’ son William Henry Vanderbilt and his wife Maria Kissam. Built circa 1850 in New Dorp, it stood on the Vanderbilt farm which had been in Cornelius’ Van Derbilt family since 1718. The farmhouse built for William ” the Blockhead” as his father unaffectionately called him, had 24 rooms and was painted white.

Despite his father’s misgivings, William would go on to be one of the richest men in America after turning the family farm into a profitable business and reviving the bankrupt Staten Island Railroad. He and his wife raised their children at the farmhouse and lived there until 1864 when William joined his father’s railroad business. The “White House” as they called it was used as a country home. It eventually passed to their son George upon William’s death in 1885. George had the house relocated to another spot on the property and built a new house of his own. Both homes were eventually demolished and the farmland was sold to the government after World War I and turned into Miller Field, an Air Coast Defense station. The station was decommissioned in 1969 and is now a Gateway National Recreation Area.

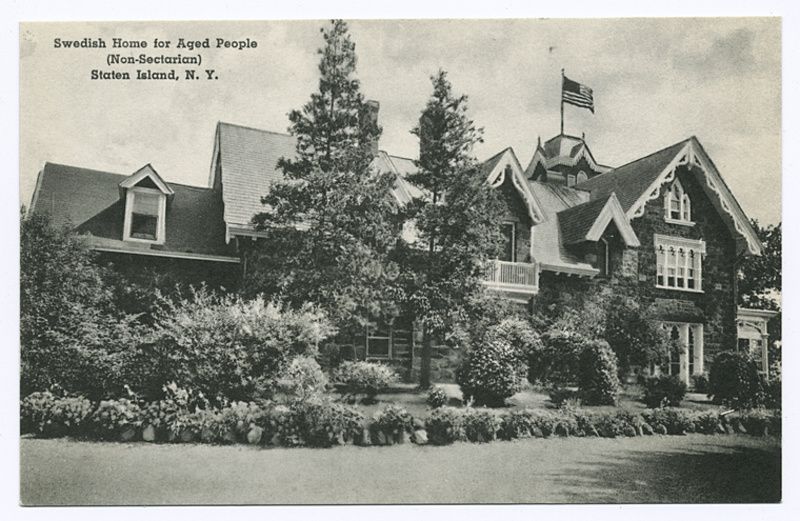

6. Swedish Home for the Aged, Sunnyside

Before becoming a home for the elderly, this picturesque mansion in Sunnyside, Staten Island belonged to a Vanderbilt. Built in 1859 for Cornelius Vanderbilt’s daughter Mary Alicia, it stood between what is now the Staten Island Expressway and Victory Boulevard. In 1912, the home was converted by the United Swedish Societies of New York into a haven for retired Swedish immigrants.

A red backhouse on the grounds was used as a place for arts and crafts and two wings were added to the home in 1940 and 1983 as more room was needed. Despite earlier growth, however, by 2008 the home was in financial trouble and abruptly closed. Despite efforts to get the building landmarked, it was demolished in 2009.

Next, check out Lost Mansions of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Hudson Valley, and Long Island!