NYC’s Forgotten ‘War on Christmas Trees’

Discover how an obscure holiday crackdown affects festive street vendors today!

“Automats were right up there with the Statue of Liberty and Madison Square Garden,” Kent L. Barwick, former president of the Municipal Art Society, lamented to the New York Times in 1991 when the country’s last automat closed. The automat, a precursor to today’s fast food chains, was a staple of the New York City dining scene in the first half of the 20th century. Originally conceived in Germany, the self-service restaurant featured coin-operated vending machines from which patrons could buy fresh coffee, simple meals, and desserts for an affordable price.

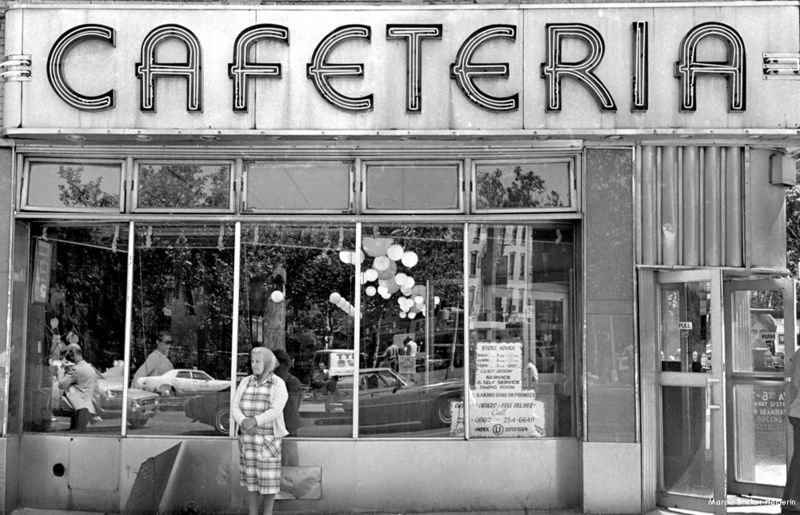

Along with automats, self-service cafeterias changed the way New Yorkers ate and socialized. In her book, Kibbitz and Nosh: When We All Met at Dubrow’s Cafeteria (Three Hills, May 2023), photographer Marcia Bricker Halperin revisits one of New York City’s most popular self-service cafeterias on Kings Highway in Brooklyn. Through Halperin’s photographs from the 1970s and 80s and essays by Donald Marguiles and Deborah Dash Moore, the book explores the story of Dubrow’s Cafeteria and the culture that sprang up around these New York City eateries. Check out our book talk with Halperin in our video archive!

Here, we take a look at 8 of the city’s lost automats and self-service cafeterias:

Automats are synonymous with Horn & Hardart. Business partners Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart opened the first automat in the United States in Philadelphia in 1902. They expanded into New York City in 1912, opening the first location in Times Square. Eventually, there would be more than forty Horn & Hardart locations in New York. One former Horn & Hardart building that still stands can be found at 2710-2714 Broadway, on the southeast corner of Broadway and 104th Street. It was occupied by the automat until 1953. A ghost sign at 146 West 48th Street marks another former location. At its height, the company had more than 150 automats and retail shops throughout Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore.

In the beginning, automats served simple foods like buns, fish cakes, and beans. Diners could also get hot coffee, brewed fresh every twenty minutes, for just five cents. In addition to having the best cup of coffee in town, the automats were also known for their striking Art Deco decor. As the company continued to grow, its menu expanded to include lunch and dinner foods like mac and cheese. pot pies, and steaks. The company even opened up retail locations where they sold packaged “to-go” foods.

The last Horn and Hardart automat, located at 200 East 42nd Street at 3rd Avenue, closed on April 8, 1991. Automats continues to be part of New York City culture today as it was recreated as a set for the fifth and final season of Amazon’s hit series The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel. In Brooklyn, The Brooklyn Dumpling Shop is bringing back the automat format of dining with new technology.

Like automats, cafeterias were waiter-less establishments. Customers would first receive a ticket with the menu items and prices. They would then approach the food counter and make selections as the server on the other side hole-punched the ticket. Taking their tray full of food, patrons then searched for a table, which was usually shared.

Cafeterias started on Wall Street in the late 19th century as a way for busy brokers to grab a quick lunch. They soon spread throughout the city and beyond. In 1929, Belarusian immigrant Benjamin Dubrow opened Dubrow’s Pure Food, a full-service restaurant in Crown Heights at the intersection of Eastern Parkway and Utica Avenue. When the Great Depression hit, however, he needed to try a new business model. Dismissing all of his waitstaff in 1931, he converted the restaurant into a cafeteria “with refinement.” In 1939, he opened another cafeteria at 1521 Kings Highway and another in Manahttan’s Garment District in 1952. Dubrow’s Cafeteria served a wide variety of dishes including Jewish staples like blintzes with applesauce and sour cream, kugels, and gefilte fish.

The self-service cafeterias of New York City offered a unique “third place,” a place outside of work and home, where New Yorkers could comfortably socialize with their neighbors, all “for the price of a cup of coffee.” In Halperin’s book, Kibbitz and Nosh: When We All Met at Dubrow’s Cafeteria, Deborah Dash Moore writes about how while the cafeterias attracted a diverse clientele, “New York Jews particularly embraced cafeterias, less as a fast-food option than as a place to sit and schmooze.” Halperin reminisces about the people she met and photographed at Dubrow’s, writing, “I met amazing people at Dubrow’s. Most were people I ordinarily would never have had a conversation with over a cup of coffee—ex-vaudeville performers, taxi drivers, Holocaust survivors, ex-prizefighters, and bookies. Women named Gertrude, Rose, and Lillian all had sad love stories to tell and big hearts.”

The Kings Highway location of Dubrow’s Cafeteria hosted a few historic moments. John F. Kennedy held a large campaign rally outside the restaurant in 1960. Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Jimmy Carter also made appearances at the cafeteria during their own presidential campaigns. It was also where Sandy Koufax announced his decision to join the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Eastern Parkway location closed in the early 1960s while the Kings Highway cafeteria stayed open until 1978. The Manhattan location shut down in 1985.

The Garden Cafeteria was a hotspot for Jewish intellectuals and writers at 165 East Broadway, on the corner of Rutgers Street. Established by Austrian immigrant Charles Metzger in 1941, the eatery has a storied history on the Lower East Side. Located next to the offices of The Forvertz/The Jewish Daily Forward, the cafeteria was frequented by the paper’s writers. Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer and photographer Bruce Davidson were among its patrons. Singer set his short story ”The Cabalist of East Broadway” at the Garden Cafeteria.

The cafeteria closed in 1983 and became a Chinese restaurant. When construction work in 2005 revealed one of the original signs, it was given to the Museum at Eldridge Street for safe keeping. The sign has appeared on display at the Museum and in an exhibit on The Jewish Daily Forward at Museum of the City of New York.

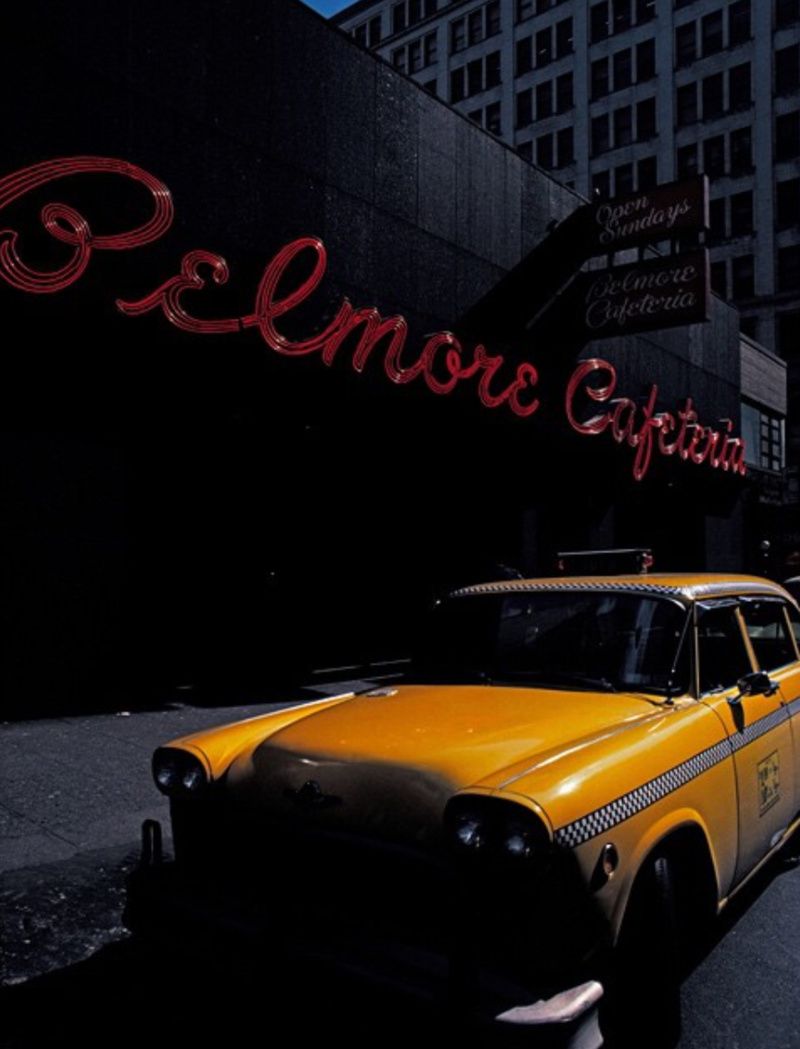

The Belmore Cafeteria once stood at 28th Street and Park Avenue South. Opened in 1929, it was founded by Philip Siegel and run by his family until it closed in 1981. Billed as “New York’s Most Fabulous Self-Service Restaurant,” the establishment attracted some interesting characters.

Members of the notorious Murder Inc. gang reportedly ate there, but the clientele the cafeteria was known for was taxi drivers. It was a common sight to see a row of taxis lined up at the curb outside. Fittingly, the cafeteria appears as a location in the 1976 Robert DiNero film,Taxi Driver. An estimated 5,000 people a day passed under the cafeteria’s glowing red neon sign and through its turnstile each weekday. In 1981, the Siegel’s sold their building and a condominium tower was built at the site.

In a 1971 New York Times article, Garfield’s Cafeteria on Flatbush Avenue was described as a “grand old cafeteria” where you could “stop in at midnight for a nosh, or something to nibble on after leaving the Alebrmarle dance parlor or to recover from the hilarity of vaudeville at the Flatbush Theater.” Like Dubrow’s, the cafeteria served blintzes, bialys, matzoh-ball soup, and more.

Since the cafeteria was open in the morning and late at night, it attracted different crowds at different times of the day. Families and old-timers usually came for breakfast and lunch, while the nighttime brought the after-theater crowds. The Times wrote that some elderly patrons would even bring their own food and sit at the cafeteria purely for the social aspect as they nursed a cup of coffee and chatted with their neighbors for hours.

Another famous Brooklyn cafeteria was Hoffman’s Cafeteria on Pitkin and Saratoga Avenues in Brownsville. This cafeteria is often mentioned alongside Dubrow’s and Garfield’s as one of the most popular. Like Dubrow’s and Garfield’s it closed in the 1970s. Hoffman’s made news in the 1940s for a butter heist. It was discovered that two of the countermen were stealing food, mostly butter, from the establishment for a period of three months. The stolen goods amounted to $15,000!

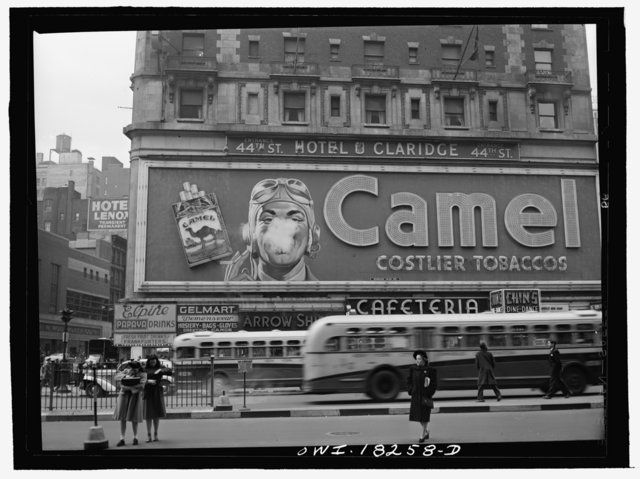

There were multiple locations of Hector’s Cafeteria in Times Square since the 1930s. The last remaining cafeteria was inside the Claridge Hotel building on Broadway at 44th Street. It lasted until 1970.

Before Hector’s closed, it made its way into pop culture. The cafeteria is mentioned in Jack Kerouac’s novel On the Road when Dean Moriarty first arrives in New York and “looking for a place to eat,” “went right to Hector’s, and since then Hector’s Cafeteria has always been a big symbol of New York for Dean.” You can also see a bit of Hector’s in this Dennis Stock photograph of actor James Dean.

Stewart’s Cafeteria occupied the first floor of an Art Deco building at 116 Seventh Avenue South in Greenwich Village. Opened in 1933, it was part of a chain of cafeterias. Stewart’s was only open for a few years before closing and re-opening as Life Cafeteria. The building still exists today (it houses a Bank of America and CVS Pharmacy) and is regarded as an LGBTQ+ history site.

Life Cafeteria attracted a bohemian clientele including gay and lesbian patrons. Unlike most places in the city at the time where homosexuality was hidden, the large windows of Life Cafeteria put everything that happened inside on display. Crowds of tourists often formed outside the windows to peer in. Tennessee Williams and Marlon Brando were known to visit, and the scenes inside have been captured in paintings by Paul Cadmas and Vincent La Gambina.

Next, check out 9 Old Fashioned Soda Fountains in NYC

Subscribe to our newsletter