Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Hoboken, New Jersey has been defined by figures like Frank Sinatra, the Stevens family, and photographers Dorothea Lange and Alfred Stieglitz. Sitting just across the Hudson from Chelsea and Greenwich Village, this waterfront New Jersey town has also been home to a French emperor, one of the “richest women in America,” and a famous composer. In this list, a continuation of our top 10 secrets of Hoboken, we explore even more fascinating stories from the neighborhood including a museum in a former shipyard to the invention of some sweet treats!

For well over four decades, a Hoboken studio in an old factory produced dozens of floats for the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. From around 1960 to 2011, float-builder The Parade Studio created witty and savvy floats out of an old Tootsie Roll factory on Willow Avenue and 15th Street. John Cheney, who joined in 1976, was one of the masterminds behind the studio’s success, as outlined in a recent profile by the Hoboken Historical Museum. Manfred Bass, the studio’s chief designer, would plan and implement projects for 30-foot-tall floats after illustrations on a paper towel. The space allowed for such tall construction projects, with 44-foot-tall ceilings, reinforced concrete walls, an overhead crane, and 16,000 square feet of space.

In 2011, the studio relocated to a larger space in Moonachie, New Jersey, located north of the Meadowlands Sports Complex. The Hoboken space, meanwhile, was demolished after serving as a Superstorm Sandy relief center. The new space is quadruple the size of the former Hoboken facility, at 72,000 square feet. It also features more advanced cutting and imaging technology. The new building also has 44-foot-tall ceilings and a five-ton overhead crane. As for Cheney, who led construction projects for the parade for decades, he continues to work on other projects including floats for the Coney Island Mermaid Parade.

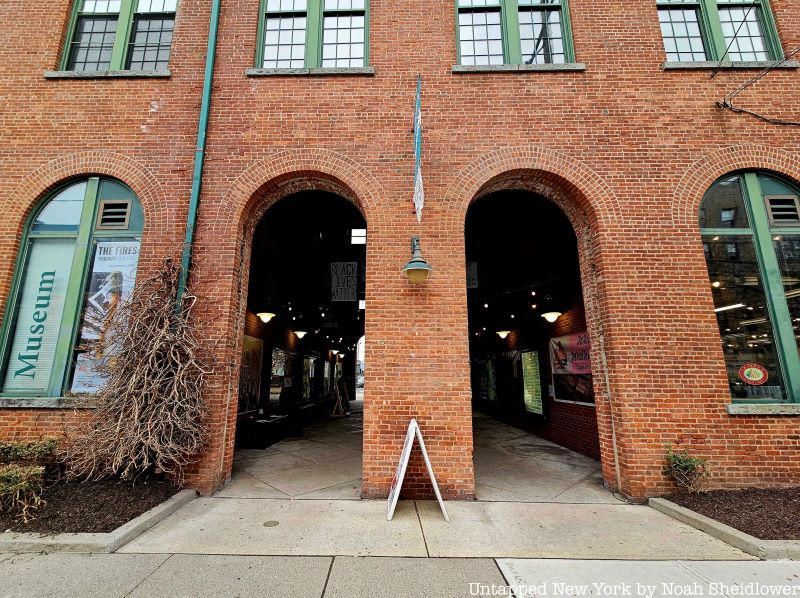

The Hoboken Historical Museum, just a short walk from the Hudson River, is located in a former Bethlehem Steel facility colloquially known as “the Shipyard.” The waterfront property was previously the site of the W&A Fletcher Brotherhood shipyard, which then became the home of Bethlehem Steel. While serving as a shipyard, workers would build and troop transport ships for World War II. The hull of ships would come into the yard, and shipbuilders would add ornate woodwork and artisan interiors. Over 20,000 people worked at the shipyard around the time of World War II. A video by the Hoboken Historical Museum from 2001 includes accounts of shipyard workers who kept the industry going.

With the cutback of government contracts in the 1960s, the facility started to decline. As the waterfront lost its significance to other deep-water ports like Port Newark-Elizabeth, many waterfront properties sat vacant, some of which were repurposed, others of which were destroyed to make way for new residential and commercial buildings. The Machine Shop, the oldest building on the Hoboken waterfront and the last building that was part of the shipyard, dates back to 1890 and has been preserved over the years.

American businesswoman Hetty Green, the so-called “Queen of Wall Street,” had an apartment in Hoboken’s Yellow Flats. Green was known as the “richest woman in America” during the late 1800s and early 1900s, though her story was not all glamorous. She lived at 1203 Washington Street, paying just $19 a month, and chose Hoboken to avoid paying $30,000 in taxes in New York. She even left Hoboken, New Jersey after receiving a $2 tax bill for her dog’s license. From a young age, Green rejected many social norms of “proper” women of the Gilded Age; instead of trying to find a Wall Street husband, she spent hours eavesdropping on their conversations. After working for her father’s whaling business in New Bedford, she met her future husband, a millionaire who had business endeavors in Asia. Green left the country for London with her husband after a forgery lawsuit.

During this time, Green began to gain attention for her investing strategy, which she described as buying low and selling high. She made $1.25 million in her first year in London, and this grew significantly as she bought up railroad stock and mortgage bonds. She returned to the U.S. and moved to Vermont after her husband suffered major losses, and she ultimately had to pay off his debt so she could transfer her $26 million to another bank. Green then moved to New York and would live at various boarding houses and flats, all the while continuing to rake in millions. She gained a reputation for miserliness, never spending more than she had to, though some characterizations of her as cruel to business partners have likely been overstated. She would lend freely and at reasonable rates to city governments amid financial panics, contrary to many media reports.

One of the top films of the 1950s, “On the Waterfront” was mostly filmed in Hoboken, unlike many other films of the time that were filmed on studio stages. The film stars Marlon Brando as Terry Malloy, a member of a waterfront gang who grapples with a deepening moral crisis. The film won numerous Academy Awards including best picture and best actor, but it would not have had the same impact if not for Hoboken. The city was packed with waterfront and industrial businesses (and was also where longshoremen would look to get connected with a mob boss to get hired). The city’s mettlesome, gritty nature made it a natural spot for the film’s subject matter.

Except for a scene shot in Red Hook shot inside a ship’s hold, most other major scenes were shot in Hoboken. Our Lady of Grace Church serves as Father Barry’s church in the film, though St. Peter and St. Paul Church nearby were used for the interior shots. Stevens Park is featured often in the film, as is River Street. Over the course of 36 days, film crews shot scenes of the city’s downtown docks between 4th and 5th Street, roofs, and bars along Hudson Street, Hoboken City Hall, Elysian Park, and Dino & Harry’s. The film also featured real-life police officers with the Hoboken Police Department, as well as a handful of actual Hoboken residents including Tommy Hanley, who believed his father was murdered by gangs by the water.

At a school in Hoboken, New Jersey in 1861, the nation’s first in-school kindergarten class took place. The Hoboken Academy, located at 501 Willow Avenue, pioneered the kindergarten curriculum beginning on February 11 of that year. The city was also home to the first teachers’ pension. Seventy-seven kindergarteners attended the school in 1861, though the school faced Church Square Park, which at the time was run-down and filled with garbage; some reports reveal that pigs and cattle would wander around right by the school.

Math, reading, and science were all parts of the curriculum, which grew to attract 450 students a year. The kindergarten was founded by Adolph Douai, who organized student clubs during the 1848 Revolutions. After being charged with treason and serving fail time, he moved to the U.S., first to Texas and then to Hoboken, which at the time had a large German community. Technically, Elizabeth Peabody founded the first kindergarten in 1859 with the help of Douai, though Hoboken uniquely integrated kindergarten into a school’s regular curriculum.

Milk’s favorite cookie, the Oreo, is a New York City invention, but residents of Hoboken were among the first to taste it. Created by the National Biscuit Company, then headquartered at what is now Chelsea Market, the Oreo was first sold to S.C. Theusen, the owner of a grocery store on 10th and Washington Streets.

Hoboken also has ties to other sweets and inventions such as the waffle cone. Italo Marchiony patented a machine to produce these edible bowls. Marchiony sold ice cream and ices from a pushcart on the streets of Hoboken in glass cups, though people kept breaking them, so the waffle cone was an economical solution. A similar cone also debuted at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis.

Hoboken played a role in the development of helpful pieces of technology, including the wireless phone. In 1914, Hoboken’s DL&W Terminal was the site of testing for the first wireless telephone, created by Guglielmo Marconi. A few years later, Hoboken was one of the first cities with wireless towers, which could transmit signal 400 miles. Among Hoboken’s other inventions was the slide rule, which was first produced at the Keuffel and Esser Complex, which has been converted into apartments. The zipper was also first manufactured at Hoboken’s Automatic Hook & Eye Company beginning in 1906.

Hoboken is often most closely associated with Frank Sinatra, and perhaps even famous photographers Dorothea Lange and Alfred Stieglitz. Even John Jacob Astor, the business magnate and real estate developer, had a mansion in Hoboken, which was constructed in 1828 and commonly hosted Washington Irving. But perhaps most surprisingly, Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, stayed in Hoboken during his exile from France.

He stayed at the corner of Washington and 1st Streets near the Astor home, which would later become the Napoleon Hotel at 100 Washington Street. The hotel preserved his table, bed, and chairs, according to an 1873 article. Napoleon III’s stay preceded his return to France in 1838, ten years before he became President of France in 1848 and Emperor of the French in 1852. According to the Hoboken Historical Museum, Napoleon III sent paintings and ceremonial vessels to Our Lady of Grace Church when it was dedicated, as well as Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. Most of these gifts have been lost, though an organ from 1899 by George Ashdown Audsley still remains.

Located further inland, Willow Terrace is a quaint and old-school private cobblestone street that dates back to 1885. Prior to Willow Terrace’s development, the area was predominantly lower-income and was inhabited mainly by Irish brick masons responsible for constructing properties in the area including Stevens Institute of Technology. Martha Bayard Stevens, the wife of the university’s founder Edwin, was likely inspired to lead efforts to establish the homes after a visit to Scotland, whose worker housing was more robust.

Martha worked with her husband and the Hoboken Land & Improvement Company to construct 108 affordable and clean homes for the brick masons, as well as community centers such as a hospital, school, and library. The homes resembled those of late-18th-century Europe on the interior and exterior, and they were built throughout the mid-1880s. Willow Terrace protected its cobblestone street and historic facades as the surrounding area become more modernized, and the homes were put on sale for as little as $500 after the company dissolved in 1940. Many of the homes remained empty by the 1980s, though high demand for the historic properties has hiked prices up to over $1 million for many of them.

One of the most defining features of Washington Street is Carlo’s Bake Shop, the subject of the TLC series “Cake Boss.” The bakery is owned by Buddy Valastro, who features prominently on the show alongside many of his family members. Though the series has brought prominent attention to the bakery since it premiered in 2009, the bakery dates back a century earlier to 1910 when it was opened by its namesake Carlo Guastaferro. The bakery survived the Great Depression and remained within the family until 1964 when it was bought by Bartolo “Buddy” Valastro, Sr.

Valastro’s son took over the business and has run it alongside his four older sisters and other family members. The shop became a tourist attraction after the show popularized the bakery’s ornate cake designs. Lines would often stretch across the block. Following the show’s success, the bakery expanded to a new factory in Jersey City to produce greater quantities of baked goods to send across the country. Since 2011, the bakery expanded from its flagship Hoboken, New Jersey location and has opened up locations across the country, including in Times Square, Ridgewood, and Westfield in New Jersey, Las Vegas, Orlando, and São Paulo.

Adding to the list of famous Hoboken, New Jersey residents, composer Stephen Foster lived at 233 Bloomfield Street in 1854. Known as the “father of American music,” Foster wrote over 200 songs including “Oh! Susanna,” “Old Folks at Home,” and “My Old Kentucky Home.” It is at his home on Bloomfield and 6th Streets that Foster, born in Pittsburgh in 1826, likely wrote “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” and other songs. Foster lived in the four-story, orange brick-shaded walk-up, which has retained two marble fireplaces to this date.

In 1853, Foster left his wife at just 27 and moved to New York City, where he stayed for about half a year before reuniting with his wife and daughter in Hoboken, New Jersey. His song “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair” was originally about his wife Jennie, though he changed the name after he once again distanced himself from his family after moving back to Pittsburgh. Some historians believe Foster’s relationship with his wife was made worse after moving to Hoboken, according to poems from his sketchbook. Foster would later move to New York City, where he spent the last four years of his life before dying at age 37.

Next, check out Part 1 of the Top 20 Secrets of Hoboken, New Jersey!

Subscribe to our newsletter