Last Chance to Catch NYC's Holiday Notalgia Train

We met the voices of the NYC subway on our nostalgia ride this weekend!

Every New York City borough has its fair share of lost mansions. Today, we are revisiting the lost mansions of Queens. Now New York City’s most diverse borough and the second most populated, the development of Queens began with farmland and suburbs. Western areas of Queens, which offered an easy commute into Manhattan but lots of land to spread out on, attracted the wealthy families of New York. There are still standalone mansions that you can spot throughout the borough, but here we revisit the country estates and follies that have been long forgotten…

This fantastical castle has inspired fantastical backstories. It was rumored that it was built by a fleeing French nobleman or that it was the headquarters of a secret society. The truth, however, is that it was built by a wealthy grocer, John Bodine, in 1853. Located at 43-16 Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City, the mansion was made of immense granite blocks and had a copper roof. It boasted a crenelated watchtower, Gothic windows, and a tunnel to the beach. These tunnels were a popular feature of grand mansions along the East River. These tunnels were used by servants to go back and forth from the house to the beach to serve guests while they lounged or partied.

Bodine lived at this castle like a king until 1880. Upon his death, the castle sat vacant for many years. It was eventually bought by a lumber company, William P. Young & Brothers. The company used the castle for offices and storage space. In 1962, the property was purchased by ConEd. Despite attempts to save the building with landmark status, the building was demolished.

John W. Rapp made his fortune in metal manufacturing. His United Metal Products Company produced steel parts for fireproof buildings according to the New York Times. His products were integral to the construction of such landmarks as the Woolworth Building (which was known for its advanced fireproofing methods) and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Building. The business occupied ten acres of land in College Point, including the former factory of Rhedania Silk Mills. His success in business allowed Rapp to purchase an opulent home close to his business. In the early 1900s, he moved into the mansion seen above with his new wife, Corine.

Located on First Avenue in College Point (now 14th Avenue), this lost mansion of Queens had lovely manicured gardens, a mansard roof, and a large porch. According to an article in the New York Herald announcing Rapp’s death in 1922, the metal mogul owned 500 acres in College Point and Flushing. The house was eventually demolished and the area was redeveloped.

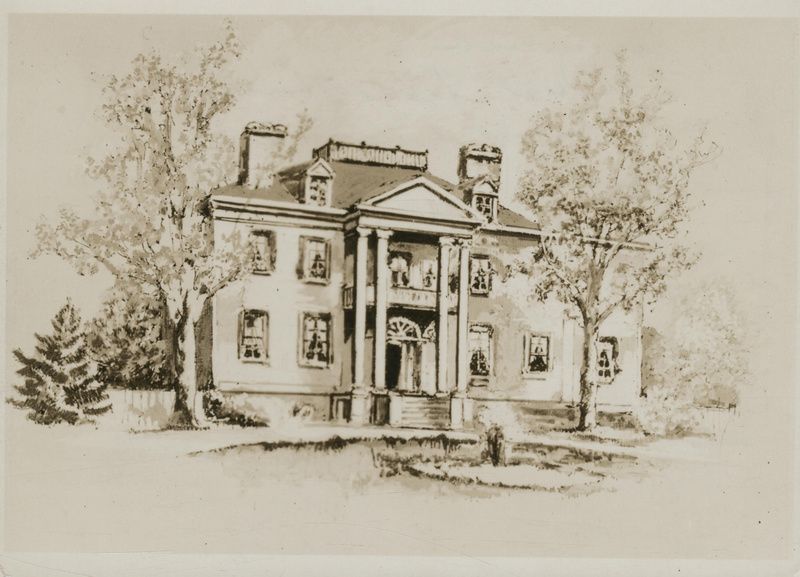

The mansion on the right side of this photograph was built by merchant Horace Whittemore around 1840 in the suburbs of Astoria, Queens. Astoria offered expansive plots of land within a short distance of Manhattan, which could be easily accessed across the East River. This classical Greek revival villa had unobstructed views of the river from its spot on what were Perrot Avenue and Franklin Street (now 27th Avenue). The Met Museum describes the interior layout of the home:

Upon ascending the outside staircase at the front of the house, traversing the portico, and entering the first floor, visitors were welcomed into a central hall flanked on the right by a pair of formal parlors and on the left by a family living room and a billiards room. On the ground level below were the dining room, kitchen, and pantries. Five family bedrooms were located on the second floor, and the third floor, with its low ceiling and small horizontal slot windows, likely housed the servants’ quarters.

Franklin Avenue in the 1800s was lined with standalone mansions. You can still see some grand homes along 12th Street in Astoria. The Whittmore House was later known as the La Roque Mansion for its second owner. The house was demolished in 1965. You can get a glimpse of what this opulent home looked like on the inside with a visit to The Met. In the American Wing, you can see the parlor with architectural details from inside the mansion. Two parlors from the home were donated to the museum by the mansion’s final owners, the Molteni family.

One of the earliest grand estates to appear in Astoria, especially around the coast near today’s Hallet’s Point, was that of Major John Delafield and his wife, Ann Hallett. Called Sunswick, their home was built in 1792, faced the East River, and was backed by a wide expanse of farmland. It was named for a now-buried nearby creek.

Delafield fell on hard financial times in the early 1800s and was forced to sell his estate to noted mineralogist Colonel George Gibbs. Gibbs and his family were known for their hospitality at Sunswick. Upon GIbbs’ death, the land was subdivided into four lots. There were multiple owners after that and the house was eventually torn down in the 1920s.

Another grand mansion that once stood along the former Franklin Avenue in Astoria was the Josiah Blackwell House. Located around what is today 27th Ave and 8th Street, the home belonged to a decsenadnat of Robert Blackwell, owner of Blackwell’s Island, now Roosevelt Island. The image of the home above was captured in 1937 by photographer Berenice Abbott.

The lost Queens mansion in Astoria remained in the family until the early 1920s when it was sold and converted to a boarding house. It was demolished and replaced by the Astoria Houses in the 1940s.

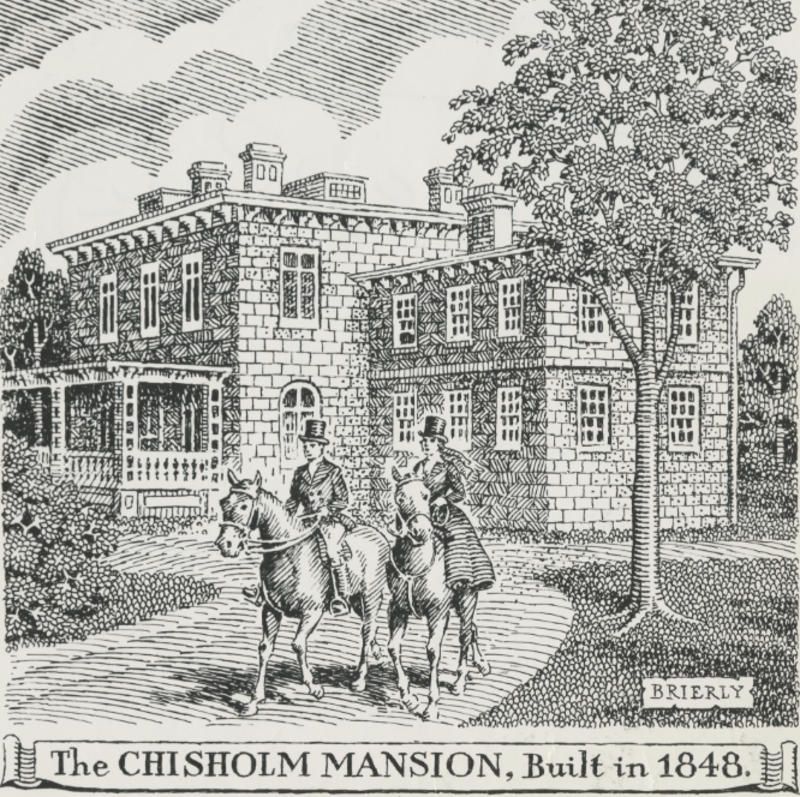

Hermon A. MacNeil Park now stands at the site of the form Chisholm Mansion. The land was originally purchased in 1835 by Reverend William Augustus Muhlenberg for a new stone Episcopal seminary. When the Panic of 1837 hit, his plans were scrapped and the land was sold to his sister, Mrs. John Rogers. She used the leftover stone from the abandoned school project to build her own mansion, at the highest point on the grounds, in 1848.

Mrs. Rogers later gave the mansion to her daughter Mary as a wedding gift when she married William F. Chisolm. The family remained in the home until 1930, when it was acquired by the City of New York. Mayor Fioerello LaGuardia used the mansion as a “summer City Hall” in 1937. Sadly, the mansion was demolished between 1939 and 1941. Today, a flagpole in the park marks where it once stood.

This old estate was technically in Nassau County, but since it’s right on the border, we’re going to include it as a bonus here in our list of lost mansions of Queens! The Oatlands Estate was created by William DeForest Manice in 1820. The estate, in the town of Elmont, was made up of 100 acres of land and dotted with multiple large buildings. The most spectacular building on the property was Manice’s Tudor Gothic mansion which sat on Hempstead Turnpike. The stone mansion had a crenelated turret and sturdy stone construction.

In May 1905, August Belmont II purchased the Manice estate. He turned it into the new home of his Westchester Racing Association. The Belmont Stakes moved from Morris Park to Long Island. The grand Manice mansion was used as the Turf & Field Club where extravagant luncheons took place in a large circular room with a live orchestra and the who’s who of New York City. It was also home to The Belmont Ball, a charity event that took place on the evening before the annual Belmont Stakes races. The mansion was used as such until 1956 when it was torn down during renovations.

Next, check out the lost mansions of Staten Island, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan, and the Hudson Valley

Subscribe to our newsletter