Lost Gilded Age Mansions are Rebuilt with Plants at NYBG Holiday Train Show®

The demolished Clark and Vanderbilt mansions are among a handful of lost NYC buildings resurrected at this festive holiday display!

The highly anticipated opening of the American Museum of Natural History’s new wing, the Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, took place today in New York City! We got a first look inside the museum addition last week and were captivated by the architecture of the new spaces and their inventive features. Here, we explore the 7 wonders of the Gilder Center, from the living specimens on display to the appealing food offerings!

The first wonder of the new $465 million, 230,000-square-foot Gilder Center is the building itself. In its design, lead architect Jeanne Gang of Studio Gang, the hip architecture firm headquartered in Chicago, seeks to heighten a visitor’s “sense of discovery and wonder” through a fluid landscape. The building’s experiential architecture encourages exploration. Critics cheered. “A poetic, joyful, theatrical work of public architecture and a highly sophisticated flight of sculptural fantasy,” wrote Michael Kimmelman in The New York Times. “A five-story well of light and space, a rhapsody of flowing structure,” wrote Michael J. Lewis in The Wall Street Journal, adding that Gilder is “lavish with sunlight.” Justin Davidson in New York Magazine calls Gilder “a theatrical and even operatic space” that feels “reassuringly luminous.” Of the three major critics, Davidson is the most cautious, saying, “The building is far from faultless, but it is gloriously imperfect, frankly attention-getting, and invigorating in its rejection of high gloss and generic bigness.” And in a phrase likely to be quoted well into the future, Davidson calls Gilder “High Flintstonian.”

All admire Gilder’s seemingly free-flowing shotcrete, trade name Gunite, a concrete mix of aggregate and Portland cement that is applied by spraying structural concrete directly onto rebar cages. This method gives Gilder its exuberant interior.

In her remarks to the press on in April, Gang emphasized that this public space is “city-facing.” In aligning with the Manhattan grid, Gilder provides a straight view down West 79th Street, for which the AMNH pink buildings had long been a terminal vista. Gang tipped her hat to AMNH’s Neil deGrasse Tyson, the astrophysicist who popularized Manhattanhenge. This phenomenon occurs twice yearly, when the setting sun aligns precisely with the street grid, creating a radiant glow that simultaneously illuminates both the north and south sides of every cross street on the grid.

When the construction fencing eventually comes down, we’ll find out what museum-going New Yorkers think of this huge new space on the Upper West Side.

Insects are the most diverse group of animals on the planet, says AMNH, encompassing more than a million species and representing over half of all known living organisms, accounting for well over 80% of animal life on earth. (Insects are classified as animals because they breathe oxygen, reproduce sexually, consume organic material, and move on their own.)

The Susan and Peter J. Solomon Family Insectarium introduces visitors to the extraordinary variety of the insect world through live insects (leaf-cutter ants hurrying along a skybridge carrying leaves!), large-scale models, interactive exhibits, observatory areas, and beautifully written explanations. The insectarium is both serious and fun, reassuring and frightening, serene and volatile.

The 8,000-pound resin model of a beehive, for example, is both educational and awe-inspiring. Sculpted by artist Karen Atta at her West 31st Street studio, the hive is composed of six honeycomb “lobes,” the smallest of which weighs 500 pounds. The largest is 3,500 pounds. The material is polyurethane resin, which is the lightest Atta could find. Hung from the ceiling, as if from a tree branch, the beehive is what organizer and designer Ralph Appelbaum calls “the grand story of the exhibit and a visual icon to the street.” The hive placement is one more example of the Gilder Center’s deference to its location on Columbus Avenue between 79th and 80th Streets.

Jeanne Gang especially admires the architectural and mathematical abilities of bees, on full display in the resin beehive. In tribute to their hymenopteran friends, Studio Gang has installed bee boxes in their Chicago offices.

The Insectarium is illustrated by magnificent insects beneath provocative phrases: Compete and Collaborate! Challenge Others! So Ancient, So Everywhere! And my favorite: What’s the deadliest animal on earth? The mosquito!

The Davis Family Butterfly Vivarium showcases some 130 species of butterflies, a few of which will happily land on your head. At first, visitors are likely to be stunned by the elegance and diversity of the butterflies. But once you’re acclimated to the warmth and humidity you’ll want to check the ID board, which is updated daily and provides an illustrated card for each species in flight. True to its educational mission the museum tells us we can help the New York Metropolitan Region’s 150+ butterfly species to thrive by building butterfly gardens: “You can invite them to your home and give them more opportunities to eat, rest, and reproduce.” Tips can be found on the AMNH website.

One of the many joys of the Gilder Center are the knowledgeable volunteers who staff the exhibits. Ralph Ferreira (left) bought his endearing butterfly shirt a few years before becoming a volunteer.

A bird lover, Gang had the many windows in Gilder fritted—printed with a ceramic dot and fired into a permanent, opaque coating—to warn birds away.

Some critics object to the presence of live insects in a museum, including butterflies and moths. Thus the security system for keeping the butterflies in their enclosure is serious. Says Gang, “Visitors pass through an airlock and the insects will be living their lives, mating, harvesting food and nectar, making cocoons, all in natural lights and among real plants. They don’t live very long, perhaps only a week. Our task is to make people want to protect them, to see the wonder of nature.”

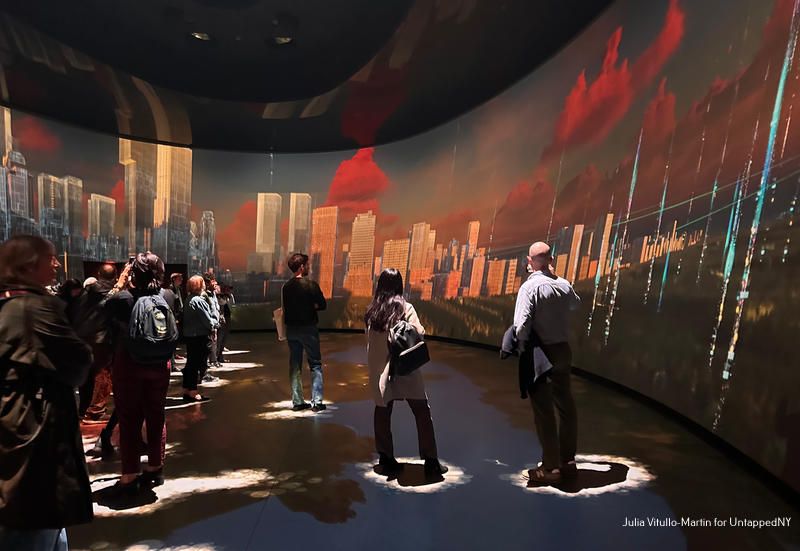

“Enter the venue at any point in the story to begin your journey through Invisible Worlds, an immersive experience based on authentic scientific data visualized like never before,” says the Natural History Museum. One landscape flows into another beneath a mirrored ceiling. Brazil’s lush rainforest morphs into a migration of jellyfish and microscopic plankton. An immense humpback whale swims through the algae and suddenly we’re in New York City, admiring the skyline that includes the World Trade Center’s twin towers in the distance.

Designed by Tamschick Media + Space with Boris Micka Associates, the 12-minute loop of Invisible Worlds seeks to provide an “emotional experience” of the unseen, moving from the genome through jellyfish to a dragonfly’s neuronal network, to demonstrate the connections among all ecosystems.

At its core, the American Museum of Natural History is about its collections—some four million specimens—and their scientific study. Kimmelman notes our ancestral interest in “diverse collections of whatever were the biggest, smallest, rarest, most exquisite or baffling objects.” Scientists would categorize objects, looking for similarities and differences. The old days were a time of “global exploration, colonial conquest, humanist curiosity, and scientific advances. Wonderment was a desired middle state between delight and instruction,” writes Kimmelman, “proving God’s inscrutable ingenuity.” And from this came scientific progress that was based on removing objects from their home territories.

Today the museum carefully states that the objects in the Maya collection, gathered by AMNH anthropologist Gordon Ekholm, were all legally removed with permission from Mexico. Ekholm had shown parallels between advanced cultures in Asia and Maya civilization, suggesting that Mayan forebears had migrated across the Pacific. A similar expedition now would leave objects in place.

The Maya bricks are from Comalcalco, an ancient archaeological site in Mexico’s State of Tabasco, adjacent to the modern city of Comalcalco and near the southern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The westernmost city of the Maya civilization, Comalcalco is celebrated for being the only major Maya city built with bricks rather than limestone masonry. The bricks on display were inscribed by their makers with various symbols and numbers. They used three dots for the number three, and a bar for the number five. Some scholars believe that the inscriptions are in some way prophetic.

The serene, high-ceilinged David S. and Ruth L. Gottesman Research Library and Learning Center gives visitors access to a range of research bases, an extensive digital repository, and scientific books—including those from its rare book collection. Dramatic views to the West remind us that we’re in the middle of the Upper West Side. The library inside the Gilder Center offers an exhibition alcove, a reading room for scholars, a group study room, and comfortable sofas and chairs.

The library has many charming touches, including these miniature hand-painted, plaster model dogs of various breeds and types from the Amory C. Simons Collection.

.

We all now know, alas, that the dinosaurs and sauropods that we had come to love were in part made up by exuberant scientists. Here is a model of Camarasaurus by Erwin S. Christman (c. 1919).

The library’s extraordinary ceiling evokes a tree fanning out above us.

The Restaurant at Gilder offers full table service—a revolutionary first for the American Museum of Natural History. And the food (described as American cuisine with regional and global influences) is fresh, elegant, and nutritious. The beverage selection highlights local breweries, distilleries, and coffee roasters. The seating is slightly austere, but that’s appropriate, and the honeycomb ceiling carries out a Gilder theme.

For the Gilder Center, opening the museum served an edible garden of steamed and raw vegetables with a Green Goddess dressing.

The Gilder Center opens at 10AM on May 4th! Entry to the new wing is included with general admission, but additional tickets are required for the Davis Family Butterfly Vivarium and the Invisible Worlds immersive experience.

Next, check out the Secrets of the American Museum of Natural History

Subscribe to our newsletter