Black Friday Sale 🎊

Explore overlooked city sights on one of our expert-led NYC walking tours!

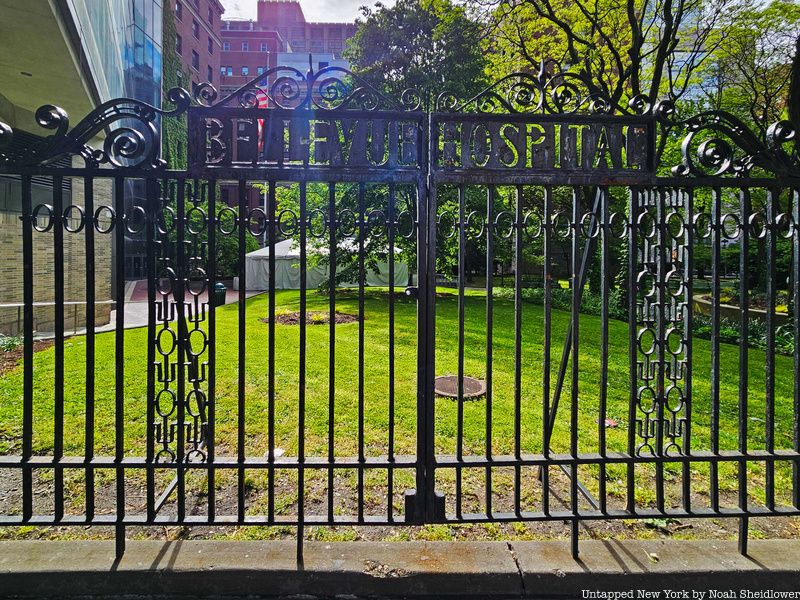

Bellevue Hospital in Kips Bay, officially NYC Health + Hospitals/Bellevue, is one of the largest hospitals in the United States. The hospital has achieved many breakthroughs throughout its history, from being one of the first to employ ambulance services to having the earliest maternity ward. Bellevue Hospital has contributed massively to the development of modern medicine but also has a dark history. At one point, the name “Bellevue” was often used to refer to psychiatric hospitals in the 1800s. The hospital made important developments in treating epidemics, from yellow fever to AIDS, and saved the lives of people from all walks of life, from the general public to presidents and celebrities. Here, we take a look back at the hospital’s long history and pull out the top 10 secrets of Bellevue Hospital!

During the tuberculosis crisis of the 19th century, Bellevue Hospital transformed ferry barges into floating wards. The floating “hospitals” were reserved for those in the early stages of tuberculosis, prioritizing indoor spaces for the many patients suffering from more severe symptoms. Poorer patients who were turned away from the barges would change their names and appearance to try for help at other facilities. It was believed that fresh air could help cure patients of tuberculosis, a disease that many believed at the time was genetic.

Once the disease was determined to be contagious in 1892, many hospitals like Bellevue would be built incorporating outdoor balconies or tall windows, such as a now-abandoned facility south of Buffalo. The floating hospital idea was replaced in part by the relocation of patients to sanatoriums on the edges of the city, such as the now-abandoned North Brother Island. Bellevue was the first hospital to report that tuberculosis was a preventable disease.

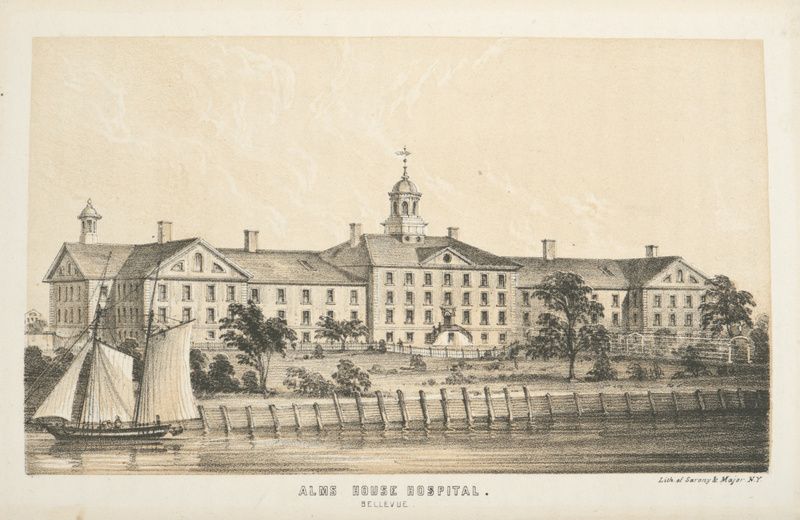

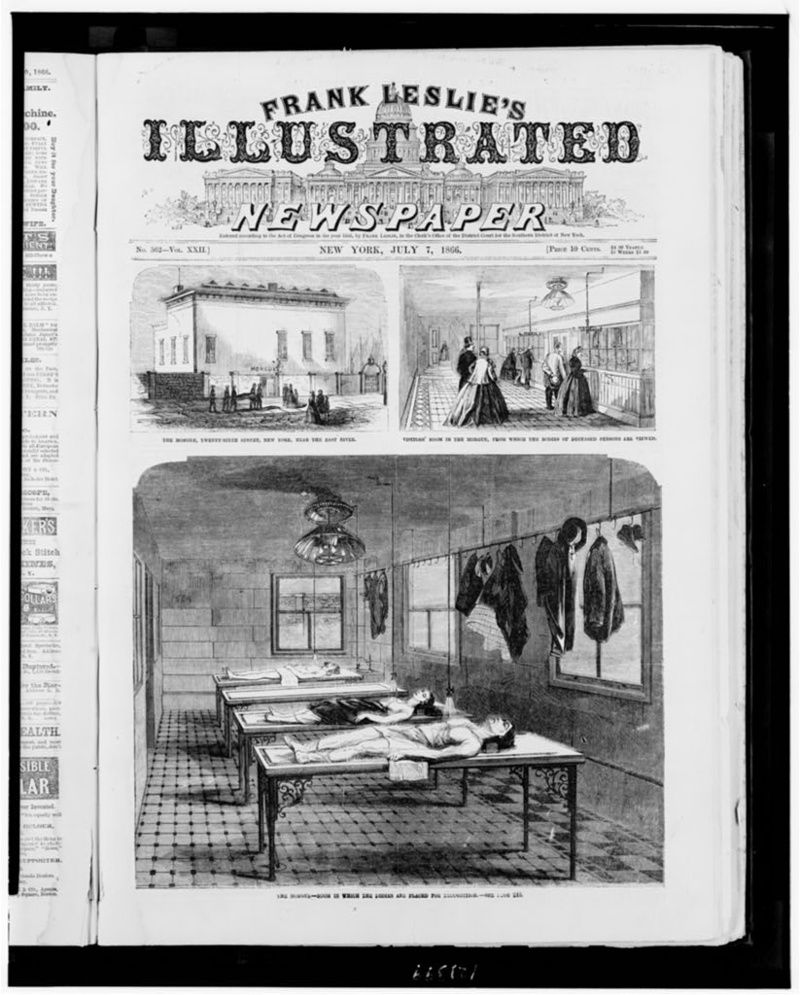

Bellevue Hospital traces its origins to a two-story brick building that stood in what is now City Hall Park. The building housed the city’s first permanent almshouse, which provided charitable housing to poorer residents. The ailing poor would move to almshouses once it became clear they would wither away from their disease; wealthier New Yorkers could more easily get doctors to come directly to their homes. With the development of more sanitary and advanced medical practices, hospitals, where all patients could go and get treatment, became all the more common. Ultimately, Bellevue became the first public hospital in the nation.

Bellevue began to employ faculty and medical students from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons around 1787. Columbia maintained its presence at the hospital until it was restructured in 1968. The present-day Bellevue Hospital was built on the previous Belle Vue Farm along the East River, which had been used to quarantine yellow fever patients as it was a few miles north of most homes. The hospital got its current name in 1824, around the time when it became better known on a national scale.

Bellevue Hospital played a significant role in the history of the emergency ambulance, as it operated the nation’s second hospital-based ambulance service. Prior to the system’s creation, those suffering from all sorts of medical emergencies had to get to hospitals however they could manage. Because getting to the hospital was a top priority, there was little emphasis placed on trying to temporarily mitigate symptoms like bleeding. A U.S. Army surgeon named Edward Dalton proposed to the New York Hospital Board that the city should adopt some form of ambulance system similar to military ambulances.

The board adopted five horse-drawn ambulances in June 1869, and according to the commissioner’s report, “Each ambulance shall have a box beneath the driver’s seat, containing a quart flask of brandy, two tourniquets, a half-dozen bandages, a half-dozen small sponges, some splint material, pieces of old blankets for padding, strips of various lengths with buckles, and a two-ounce vial of persulphate of iron.” This paved the way for emergency ambulance services at Long Island College Hospital and Eastern District Hospital in 1873.

By 1891, the Bellevue Hospital received 4,392 ambulance calls per year. The sheer quantity of calls led the hospital to have “the record for the largest number of telephone calls to any public institution in the country.” Though, the hospital needed a more efficient system that would ensure faster arrival times and less confusion. Calls would first go to Madison Square Central Office, which would then be dispatched to the local police headquarters, which then would have to contact the particular hospital. Nothing changed until 1967 when President Lyndon B. Johnson recommended that a single number be created for emergencies, thus sparking the birth of 9-1-1.

In addition to being the first public hospital in the U.S., Bellevue Hospital achieved a significant number of medical firsts that have paved the way for major developments in medicine and other treatments.

In 2013, Barnum and Bailey’s Circus revived a decades-old tradition at Brooklyn Hospital Center: performing for patients and staff. The tradition was started at Bellevue Hospital, and some performances would feature everything from acrobatic stunts to elephants. These performances would often attract thousands of people, many of whom were children and members of the community. The tradition began in 1901 and would continue each year for decades, with patients often watching from the hospital’s iron balconies.

“Dr. Ringling’s medicine is of the finest quality, easy to take, good for almost any ailment; children love it and adults enjoy it,” Dr. William F. Jacobs, Bellevue’s medical superintendent, told The New York Times in 1946. “I’ll prescribe it any time in same dosage for young and old alike.” More than 4,000 patients at Bellevue, some on stretchers and in wheelchairs, applauded clowns, six adult elephants, a baby elephant, a zebra, and a llama, according to a 1964 Times article. The tradition ended in the 1960s when the iron balconies were removed.

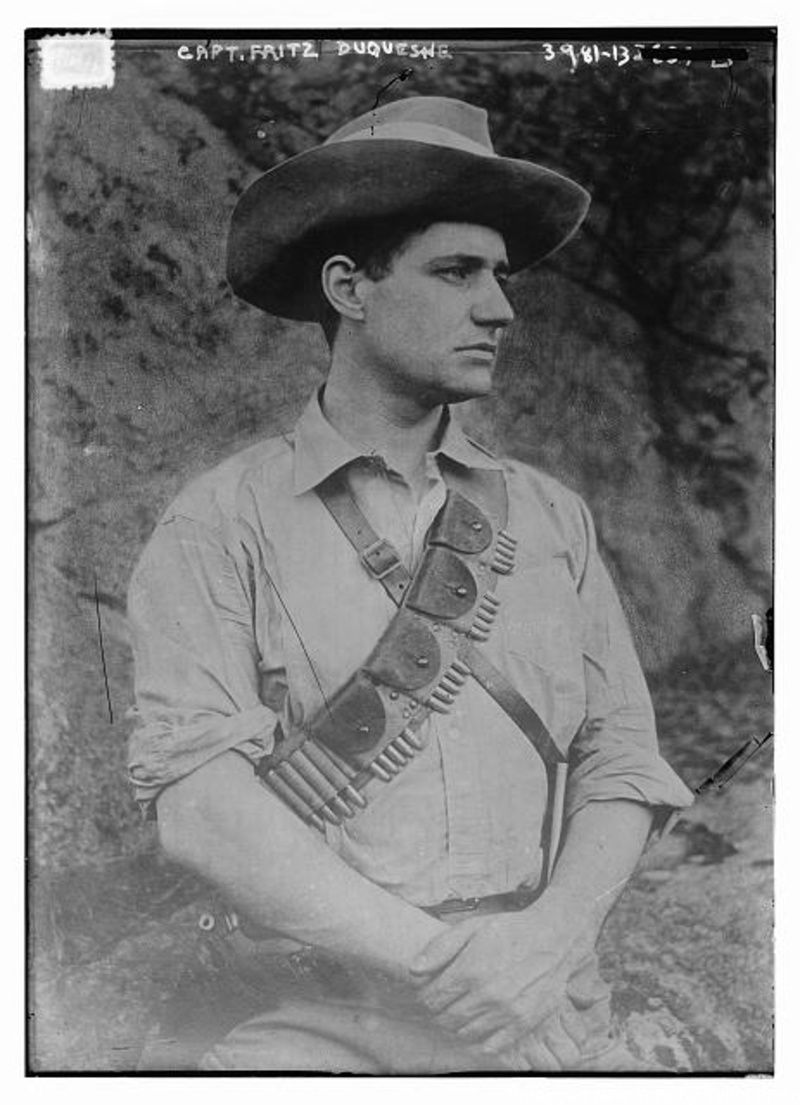

Perhaps one of the hospital’s strangest encounters with a patient was with Fritz Joubert Duquesne. He was a German and South African Boer soldier and journalist, though he was perhaps best known for being a spy. Duquesne would frequently lie about his identity, reinventing his past and asserting he was related to royalty to get into (and out of) high-stakes situations. He gathered human intelligence for the Boers during the Second Boer War and led spy rings in Great Britain, Latin America, and the United States. He was captured by multiple governments. In 1917, federal agents in New York charged him with insurance fraud for insurance claims, after which the agents discovered evidence that he was involved with multiple ship bombings.

Knowing he would potentially be extradited to the U.K. on murder charges, Duquesne pretended to be paralyzed and was subsequently sent to Bellevue Hospital’s prison ward. Until May 1919, Duquesne faked paralysis in his right leg, carrying a cane to play the part. Just days before his extradition, Duquesne disguised himself as a woman, cut the bars of his cell, and climbed over the ward’s walls to escape. He successfully fled to Mexico and then Europe, and it wasn’t until 1926 that he was documented again, this time under yet another identity.

Bellevue Hospital was one of the key players in the fight against the AIDS Crisis in the 1980s. In 1981, Bellevue reported one of the first three cases of HIV/AIDS, which at the time was an unexplained immunodeficiency. Over the next few years, the hospital worked to identify the disease and pioneer treatments. In 1985, Bellevue opened the country’s first hospital-based HIV nutrition program. That year, Coler Memorial Hospital led the country in allocating long-term care beds to people with AIDS, while Jacobi opened Kroc Day Care Center for Children with HIV.

The following year, HHC hospitals including Bellevue opened clinics for AZT, the first antiretroviral drug. By 1990, throughout HHC’s 11 hospitals, 1,100 new AIDS patients were admitted daily. In 1997, after years of treating HIV/AIDS patients, Bellevue participated in an NIH clinical trial examining the use of antiretroviral drugs in children and infants with HIV. The hospital further participated in trials for Nevirapine, given to HIV-positive pregnant women, and for combination drug therapies. Bellevue played a key role in developing HAART, or the “Triple Drug Cocktail,” to treat the disease.

Bellevue Hospital has treated thousands upon thousands of New Yorkers, from celebrities to those who could barely afford treatment. Among these have been some famous and unfortunate cases involving major historical figures. One of the most famous literary references to Bellevue was in Allen Ginsberg‘s poem “Howl,” inspired by his time at the hospital. One of the most notable patients was Mark David Chapman, who received treatment after murdering John Lennon. Chapman had medical appointments at Bellevue in between his stays on Rikers Island. Another violent patient was Norman Mailer, the American novelist behind The Naked and the Dead who was treated at Bellevue after stabbing his wife. Mailer was convicted of assault for nearly fatally stabbing Adele Morales with a penknife, for which he received three years probation.

On the flip side, however, the hospital treated James Garfield after he was hit by two bullets in 1881. Garfield was shot at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station by Charles Guiteau, who erroneously believed he should have been rewarded with a consulship for helping Garfield win the election. Bellevue’s Frank Hamilton and his team came down to Washington to treat Garfield’s wounds, though he would die two months later from infection. Garfield was not the only president Bellevue treated; Grover Cleveland came to Bellevue after discovering a cancerous mass in his mouth amid the Panic of 1893. To avoid suspicion, Cleveland was treated on a yacht in the East River by numerous Bellevue medical faculty, which was ultimately successful after nearly two hours.

Bellevue made national headlines in 2014 when it treated the city’s first Ebola patient, which put the city on edge for a few months. The hospital treated Craig Spencer, who treated Ebola patients in Guinea through Doctors Without Borders and contracted the virus himself before heading back to the U.S. He was placed into isolation at Bellevue as investigators tried to piece together everyone he had contact with in the days prior; he had taken the A and L trains the day before, as well as took a taxi. The virus could not be spread until symptoms began to show, though, and it couldn’t be spread through the air, though the bowling alley he had frequented the night prior remained shut for a day.

In 2019, the hospital conducted an emergency exercise to transport a simulated Ebola patient from Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Jersey to Bellevue’s Regional Ebola and Other Special Pathogen Treatment Center. The experiment was performed in the wake of an Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, resulting in 1,100 cases and 700 deaths. The experiment, whose results could be shared with African nations, tested the feasibility of safe patient transport, including the use of biocontainment devices and personal protective equipment, as well as appropriate decontamination procedures.

Amid the sound of ambulances is a surprisingly peaceful sculpture garden near the water called the Bellevue Sobriety Garden. The quarter-acre park between First Avenue and the FDR Drive includes sculptures, mosaics, plants, and other artistic features. The Sobriety Garden, as its name suggests, was begun by Bellevue psychiatrist Dr. Annatina Miescher in 1989 who got recovering addicts from its Chemical Recovery Program to help tend the plants. The park was almost destroyed in 2006 after proposals were put forward for additional parking, though patients and staff objected.

The fairly secret garden includes all sorts of sculptures of human figures and animals, though in 2014, dozens of animal sculptures were vandalized. According to a 2014 New York Times article, “The faces of rams were cracked and crumbling. The neck and beak of a bird sculpture were broken and hanging to the side.” The cement, sand, and chicken wire sculptures, many of which were created by patients, were left scattered across the garden. Since then, the garden has been attended to by hospital staff, counselors, volunteers, and patients who have worked to restore the garden. You can see it now in full bloom in the spring and summer months!

Next, check out the Top 10 Secrets of Sea View Hospital on Staten Island!

Subscribe to our newsletter