You Can't Eat the Food at this MoMA Mart Pop Up in NYC

Nothing in this pop-up store is what it appears to be!

From doors that lead to nowhere to miles of underground book stacks, uncover the top secrets of the New York Public Library!

Libraries are places of wonder that inspire and satisfy the inquiries of curious minds, and there are few libraries that do so better than the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building. Standing proudly between Fifth Avenue and Bryant Park, the New York Public Library's midtown branch—often referred to as the “main branch” of the city’s public library system—is an invaluable research resource, an architectural treasure, and a historic New York City institution.

The New York Public Library (NYPL) was founded in 1895 when already established library institutions created by John Jacob Astor and James Lenox were combined, along with a fund created by Samuel J. Tilden. These three components created a new free and public library system. The building that would house this new library was designed by the renowned architecture duo of Carrère and Hastings. The library was officially dedicated on May 23, 1911, sixteen years after the historic agreement between Lenox and Astor. Inscriptions on the facade of the building, above the main entrances, note the three founding institutions.

Now, more than 100 years later, the library continues to serve the intellectual needs of New Yorkers, expanding to 92 locations and four research centers systemwide. The original midtown library building, now considered the main branch of the system, is the second largest library in the nation, just behind the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C, and one of the largest in the world. Within its walls, the library holds not only millions of books and priceless artifacts but also many secrets waiting to be discovered.

While writing her book The Art Spy, Untapped New York's founder Michelle Young got lots of work done at The Frederick Lewis Allen Memorial Room inside the library. The room is available to authors under book contract and offers a space where they can access the library's immense general research collections. The Allen room is part of library's Gregorian Center, a section of the second floor with study rooms reserved for researchers. You can learn about how to reserve a spot here!

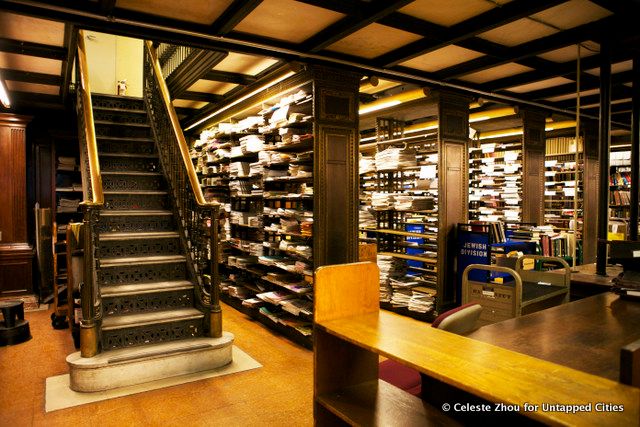

If you’ve ever walked into the New York Public Library and wondered, “Where are all the books?” the answer lies beneath your feet. Around 4 million books are stored in subterranean stacks beneath the library building and Bryant Park. The library contains 125 miles of shelving both above and underground, including 88 miles spread throughout the seven stack floors of the Humanities and Social Science Library, and 37 miles in the two-level stack extension under Bryant Park called the Milstein Research Stacks. If you look around Bryant Park, you can spot a door in the ground that serves as an emergency exit for the underground stacks.

The self-supporting steel stacks serve as structural elements of the building. The stacks act as buttresses to the floor of the Rose Main Reading Room, which stretches the length of nearly two full city blocks. Snead & Company Iron Works of Jersey City, New Jersey, were the contractors for the stacks which are made up, in part, of Carnegie steel. In addition to the sprawling stacks beneath the New York City site, there are also millions more books stored in an off-site facility in Princeton, New Jersey.

Getting fresh and clean water to New York City was a major challenge in the early 19th century as the city rapidly expanded. The solution to the city’s water needs was the Old Croton Aqueduct. Construction started on this water transportation system in 1837, and water first flowed through it in 1842. The aqueduct moved water from the Croton River in upper Westchester County down into Manhattan. The water was stored in a receiving reservoir which was located where the Great Lawn of Central Park is now, and was distributed from a reservoir at the current site of the Schwarzman building. That reservoir was known as the Croton Reservoir.

The Croton Reservoir held 20 million gallons of water within its walls, which stood 50 feet tall and 25 feet wide. Edgar Allan Poe frequently walked atop the reservoir walls to enjoy the view they offered of the city. When it became obsolete in the 1890s, it was torn down to make way for the new library building. It took two years and some 500 workers to dismantle the reservoir. The cornerstone of the library was laid in 1902. The Old Croton Aqueduct would serve as a vital water supply for New York City for nearly a century until a new aqueduct was built, which remains in service to this day. Inside the library, you can still see pieces of the reservoir walls if you look for the rough stone between the stairs on the lower levels of the South Court, near the Celeste Auditorium.

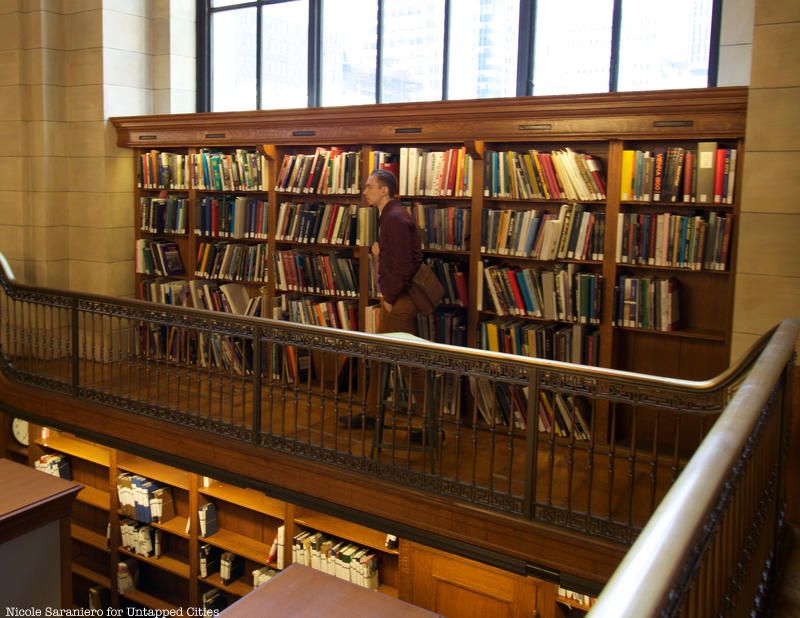

The Rose Reading Room houses the library’s General Research Division and serves as the central research hub in the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building. This area is open to anyone who needs to look something up, and most of the books are easily accessible in the open stacks. However, there is a second level of stacks above the main floor, and it’s not apparent how to access them. Ringing the Rose Reading room is an elevated mezzanine for employee use only, so if you need a book from this section, you need assistance. In addition to access to the second-level stacks, the catwalk offers a great view of the space.

In order to get to the top of the catwalk, there are tiny hidden spiral staircases behind doors that are locked to the public. On a recent visit to the New York Public Library, Untapped Cities Insiders were granted special access to walk atop the catwalk and take in the amazing views it offers of the reading room. Untapped New York Members got to walk across the off-limits level on a series of tours run in partnership with the NYPL!

Want access to more amazing one-of-a-kind experiences like this?

The stunning Rose Reading Room inside the New York Public Library underwent a major restoration from 2014 to 2016. The intricate plasterwork of the ceiling was restored, the mural was recreated and the lights got an upgrade. The historic room also got a new mode of book transportation, a “book train.” Before the advent of the book train, books from the tracks were transported via a conveyor belt system and dumbwaiter for oversized books.

The electrically powered train is made up of twenty-four individual cars which can carry up to thirty pounds each. The swinging design of the train’s carts allows them to move in multiple directions and remain upright while switching from horizontal to vertical positions. The train runs on 950 feet of track over the course of eleven levels. It travels at seventy-five feet per minute, which means it takes just five minutes for a book to travel from the stacks below to the Rose Reading Room.

Until a few years ago, the New York Public Library still used pneumatic tubes to fulfill book requests. To request a book from the stacks, you would fill out a call slip that would be sent through the tube to one of the eight levels of stacks where an employee would find your book and then send it via conveyor belt to the same spot where you submitted the slip.

The system was so efficient that it mainly went out of use because the canisters were too difficult to replace. Officially retired only a few years ago, the pneumatic tube system was receiving upgrades and new installations until 1998 according to Atlas Obscura. You can still see the tubes in the library today in the Rose Reading Room.

Have you ever noticed the tiny doors with mini balconies on the exterior facade of the New York Public Library, set between the arched windows of the Rose Reading Room? Clearly not level with the floor of the Reading Room and not proportionate to the monumental scale of the building, it was a mystery where these doors led and what their purpose was.

It turns out that those doors can be accessed from the catwalk of the Reading Room. Between the windows, there are wooden doors that open up to a few stairs and a short, undecorated passageway that ends at the tiny door that can be seen from the outside. When Untapped Cities discovered this, there was a foreboding sign on the door that read, “DANGER! DO NOT UNLOCK THIS DOOR!” and a window with cross bars. Photographer Max Touhey explained to us that, according to the New York Public Library, the doors were built as part of a planned extension of the building which never happened. He also says one of the windows opens and offers a view of Bryant Park.

The New York Public Library required six times more marble than was used in the construction of the New York Stock Exchange and the New York Chamber of Commerce combined. At the time it was complete, the library contained 530,000 cubic feet, or roughly 4 acres, of white Vermont marble which came from two quarries on Dorset Mountain. In 1911, this made the New York Public Library the largest marble building ever built in the United States. Marble pieces that didn’t meet the high standards of the library’s architects were incorporated into other contemporary buildings including Harvard Medical School. Inside, there are various different types of marble found throughout the library. One gallery is clad in Pentelic marble, the same type of marble used to create the Parthenon in Greece.

The exterior marble on the library’s facade is twelve inches thick and the cornerstone alone weighs 7.5 tons. The splendor of the stone continues inside the library and is on grand display inside Astor Hall. Visitors to the library walk into Astor Hall from the Fifth Avenue entrance. To this day, this room is the only room in New York City constructed entirely of marble, from floor to ceiling. Even the candelabras that illuminate the space are made of marble.

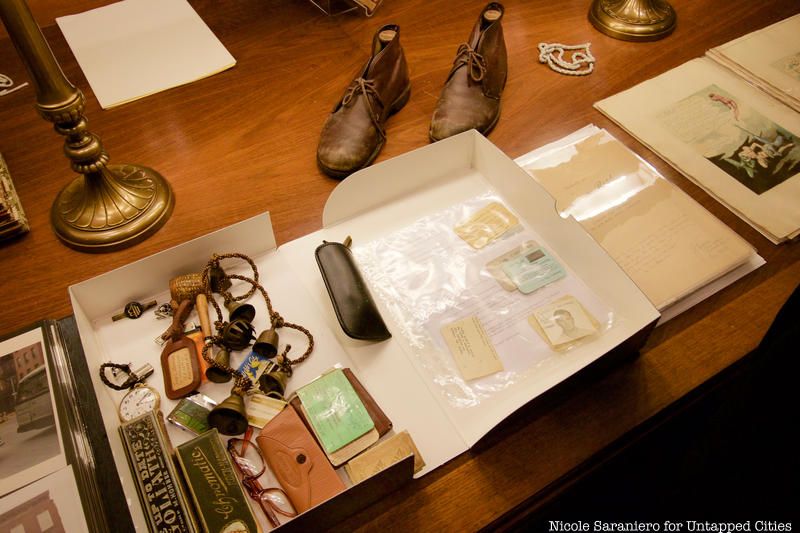

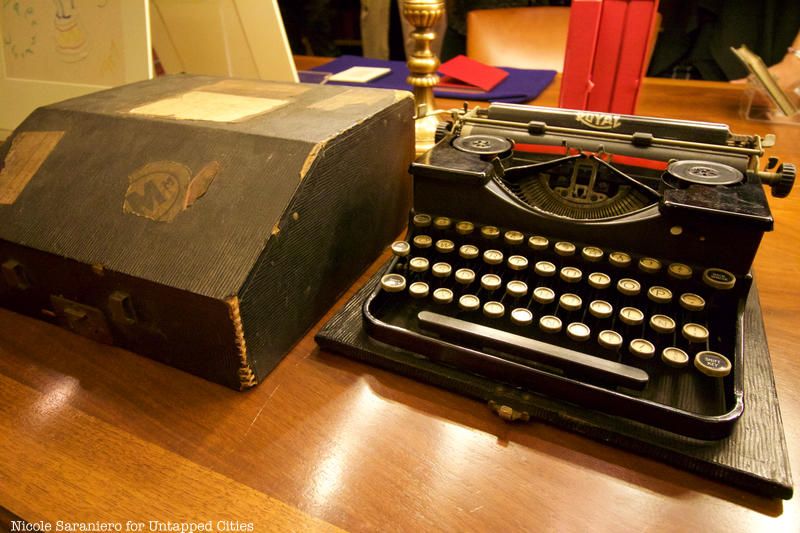

The New York Public Library has innumerable treasures tucked away in its stacks. In addition to millions of volumes, the library also possesses priceless historical artifacts. Some of the library’s items can be seen in their rotating special exhibitions and you can request to see certain items if you are conducting research. Among the amazing pieces found at the library are literally thousands of Virginia Woolf‘s personal letters, e.e. cummings‘ typewriter, boxes of personal items that belong to writer Jack Kerouac (including his shoes, library card and prayer bells), Charles Dickens‘ writing desk, a handwritten poem from Emily Dickinson, George Washington’s recipe for beer, even pieces of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s skull!

On a recent Untapped New York members-only visit to the library while showing highlights of the Berg Collection, including an annotated copy of T.S Eliot’s The Waste Land and tiny pieces of paper containing writing from the Brontë siblings, curator Carolyn Vega explained that part of what makes these items so important is that it gives a glimpse into the creative process of some of the world’s most famous writers.

Many of the library’s fascinating artifacts can be seen on display in the library’s first permanent exhibition, the Polonsky Exhibition of The New York Public Library’s Treasures. There you can see items like the original Winnie the Pooh dolls, a copy of the Declaration of Independence, and more!

The New York Public is an extremely valuable resource with extremely valuable items inside of it. During World War II, after the attack of Pearl Harbor, many of the library’s most valuable books and manuscripts were taken off-site to safer locations. Relocated items were taken to bank vaults around New York City and 12,000 other items from the collection, valued at that time at $10 million, were temporarily moved to a secret location 250 miles away.

World War II prompted many precautions to be taken around New York City to protect its most important buildings. Windows atop Penn Station, which at the time was a grand Beaux-Arts structure designed by McKim, Mead, & White, and the original City Hall subway station, were blacked out, baseball games weren’t played at night, and the Statue of Liberty‘s torch went dark, all for fear of becoming targets of a bombing. During the War, the library even served as a helpful resource to the military, which made use of its Map Division to the coastlines of enemy countries.

Known today as Patience and Fortitude, the lions who stand guard at the entrance of the New York Public Library have gone by many names, but officially they don’t have names. Sculpted out of Tennessee marble by Edward C. Potter, they were originally called Leo Astor and Leo Lenox after the library’s founders, John Jacob Astor and James Lenox.

There was a time when they were called Lady Astor and Lord Lenox, though both lions are male. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia was the first to call them Patience and Fortitude. He chose these names because he felt they represented the virtues needed for New Yorkers to weather the Great Depression. The name has stuck ever since. Patience sits on the south side of the steps and Fortitude on the north.

Subscribe to our newsletter